Wrestling with Next-Gen Emotions

What do Shinji Mikami, David Cage, and Bobby Kotick have in common? The notion that storytelling is a technical hurdle as much as a creative one

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

New consoles are just around the corner, which means we're entering yet another golden age of marketing stupidity. Whether it's vague promises of "harnessing the cloud," declarations that the new machine is 8, 10, or 40 times more powerful than its predecessor, or fun facts about how many billion transistors have been crammed into gamers' new toys, the industry is showing all the shame of a used car salesman these days.

Now this happens with every new generation of consoles, but hardware makers always seem to struggle when it comes down to telling gamers why they should actually care about these promises of power. The perfectly legitimate--if perhaps a bit underwhelming--reason is that players will get better looking games on the new systems. And yes, in some cases the more powerful systems may allow for a few novel games that would have been technically impossible on earlier consoles (Mario 64 wasn't going to happen on the Super Nintendo, after all). But that reason isn't enough for a proper marketing push. It doesn't communicate the idea of this new tech as a must-have. It won't trend on Twitter, or inspire people to start camping out on the Best Buy sidewalk. It doesn't create a buzz.

So instead, developers, publishers, and hardware makers alike try to translate that promise of power into things they think gamers might care about. They try to convince players (and probably themselves) that these new systems will facilitate some sort of breakthrough for gaming. They'll pole vault the industry over the uncanny valley, create true artificial intelligence, and figure out a perpetual motion machine while they're at it. But one of the more persistent and perplexing assertions is that this power will produce emotion.

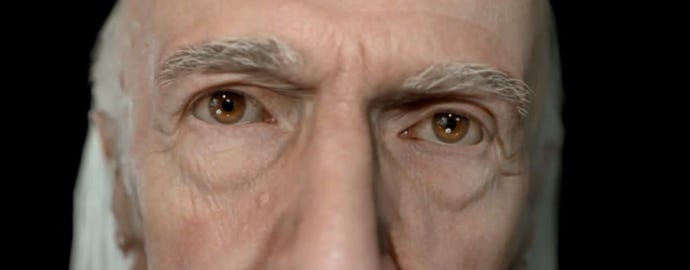

David Cage is perhaps the lead figurehead/punching bag for this point of view. As the Quantic Dream founder said at the PlayStation 4 reveal event, "When people ask me, 'What is the feature you want the most on next-generation platforms,' my answer is always the same. Emotion."

Cage then went on to talk about polygon counts, advanced skin shaders, 3D depth of field, and other technical tricks. The Heavy Rain director did not mention the value of skilled storytelling, supporting all of the choices presented to players, or coherent worlds with consistent logic.

"When people ask me, 'What is the feature you want the most on next-generation platforms,' my answer is always the same. Emotion."--David Cage

Sadly, Cage is not alone in his belief--or at least his public decrees--that technology is the barrier holding games back from inspiring emotional reactions from players. And it's perhaps telling this sentiment is not coming exclusively from the creative side of the industry.

In 2009, Activision Blizzard CEO Bobby Kotick created a stir when he told investors he was trying to take the fun out of making games and instill a culture of skepticism, pessimism, and fear. Elsewhere in that same conference call, Kotick said Activision was working to push the envelope in emotional game experiences. As for how the company was doing that, Kotick talked about a real-time rendering and mouth movement technology Activision had been working on for the next-generation of systems (which we now know as PS4 and Xbox One), suggesting it could revolutionize the industry, and finally allow games to establish a compelling emotional attachment with players.

Back to the creative side, Shinji Mikami told GamesIndustry International last month that next-gen tech will make his new horror game "a lot scarier." The only scary thing here is that this sentiment came from Mikami, creator of the original Resident Evil and a key figure in the survival horror genre. He of all people should understand how much of horror is in the audience's minds, the nervous anticipation when the threat is suspected but not seen, the power of imagination to create monsters far scarier, uniquely tailored to their own fears, and more vivid than anything rendered in 4K resolution.

As anyone who has loved a game before probably understands, emotional engagement is not dependent on polygon count. In fact, it's often the most abstracted or graphically crude games that engage players the most, games like Passage or Freedom Bridge. By offering so little up front, these games force players to fill in the blanks, to flesh out the world of blocks and bleeps until it exists as much in their own imaginations as it does on the screen.

These new systems are simply better tools for developers. And it's true, better tools can facilitate better creations. But expecting them to make better creators is like expecting Beyond: Two Souls to make more sense than Heavy Rain because David Cage got a new version of Microsoft Word.