Where Has All the Funny Gone?

Games made expressly for the purpose of comedy seem to be growing more endangered by the day. Why is that?

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

We play games for many reasons: to unwind, to feel empowered, to experience the adrenaline rush of fear, to explore strange and fantastic worlds, and sometimes, for the simple, obsessive joy of watching stats grow in number. But rarely, if ever, do we play games to laugh.

Of course, we're not dealing with a completely humorless medium. Plenty of games have their funny moments, and even more that don't strive for humor become unintentional comedy classics. Take at look at the Internet's most infamous memes, and you may notice a massive chunk of them originate from the clumsy localizations, not-quite-there technology, or bizarre logic of video games from the past. But these references don't necessarily have to stretch back to our industry's Bronze Age: Skyrim's "arrow to the knee" meme has barely been A Thing for three years, yet it already feels as ancient as Zero Wing's "all your base are belong to us." (But at least the latter has a catchy theme song.)

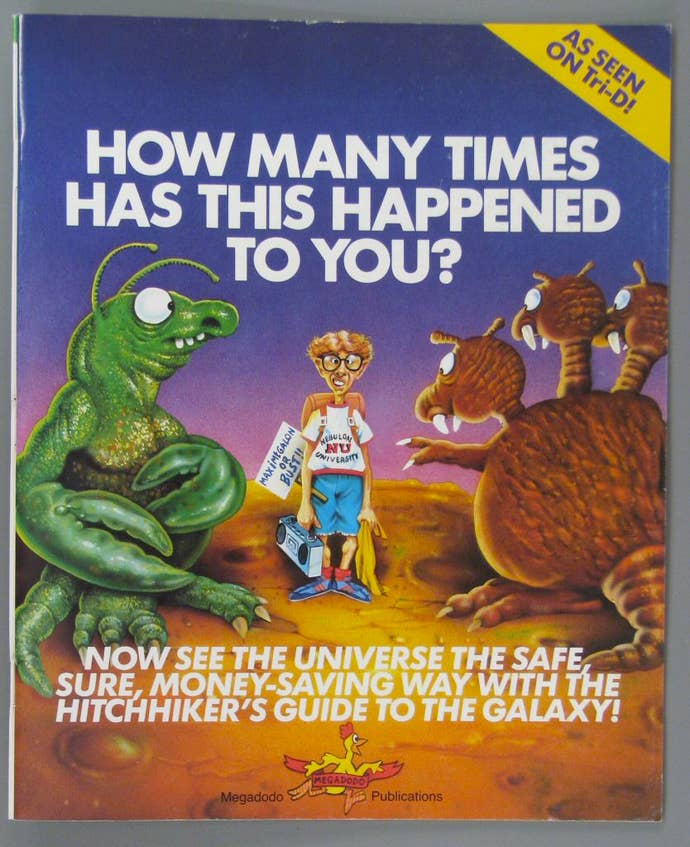

If you want to witness an age where video games provided a perfect setting for comedy, you'll have to travel all the way back to the early days of personal computing, when interactive fiction, and later, traditional adventure games, took a very literary approach to making players laugh. In this era, computer games distinguished themselves from console and arcade games by offering more cerebral experiences—and it certainly helped that many PCs could pull off rendering text and static images far better than fast-paced action. The early '80s saw the release of a Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy text adventure, co-designed by original author Douglas Adams, who went on to write a completely unique adventure for publisher Infocom a few years later. If gaming managed to lure in one of the biggest guns of comedy writing, surely, there must have been some belief that the domain of Pac-Man and Super Mario could somehow be an excellent format for humor.

And no developer sought to prove this hypothesis more than LucasArts (formerly Lucasfilm Games), whose library of classic adventures focus on humor more than any other quality. Their golden age barely lasted a decade, but in that short amount of time, the developer established a signature style that featured oddly specific characters and settings, and a host of activities players most likely never experienced before in a video game. Even in the days before their games offered dialogue trees, adventures like Maniac Mansion entertained through the sheer absurdity of their premises: No other experience at the time let players feed wax fruit to otherworldly tentacles, microwave hamsters, or write the memoirs of a slimy meteor bent on world domination. And the introduction of the "talk" command to LucasArts' games only gave these productions more comedic potential: Since they never punished players with unfair deaths, anyone pointing and clicking their way through Monkey Island, for instance, could easily make protagonist Guybrush a sarcastic bastard, or a naive dullard, since each branch of dialogue served the same purpose, but presented the possibility of a new joke.

We're two decades removed from LucasArts' heyday, and the premise of the "comedy game" feels like a completely foreign concept. To be fair, Telltale Games made a fine attempt to recapture that same magic throughout the mid-to-late '00s, and some of their final, comedy-focused adventure games—like Sam and Max: Season 3 and Tales of Monkey Island—feel like direct evolutions of what came before. But now that the company has chosen to focus on dramatic TV and movie properties instead of continuing the LucasArts tradition, mainstream gaming has seen fewer games that focus on comedy, rather than layering it atop a barely related experience.

If you search for a funny game these days, most people will point you in the direction of Borderlands, in which comedy is there for texture, but not out of necessity. And, as someone who's played hundreds of hours of the series, I can't say it particularly works. Anyone is free to enjoy it, of course, and the games still manage to crank out some good one-liners, but Borderlands is essentially an experience that involves shooting the same things over and over, even if the quests try to dress up this basic act with sociopathic zaniness. Simply put, the humor in Borderlands doesn't feel attached to what you're actually doing in the game, which makes it come off as superfluous. It's fine when characters jabber at you in the act of blasting apart enemies with randomized weaponry, but when you're trapped in a room, waiting for them to finish their spiel, it can be absolute torture.

While it's not always completely successful, the Saints Row series understands comedy in games comes from what you do, not just what you hear. While the series started as somewhat shameless GTA ripoff, its developers soon realized the main reason people played its inspiration: Not for the gripping story or biting social commentary, but to dick around with mods, cheat codes, and anything else that could enable a ridiculous virtual killing spree. As Grand Theft Auto dialed back on player freedom, Saints Row honed in on the main reason to approximate a virtual world: The chance to play out pure craziness in a realistic setting. The writing might think it's a little more clever than it actually is, but that's easily forgiven, as Saint's Row draws from the LucasArts tradition of making both your actions and objectives completely ridiculous.

Funny games might be an endangered species, but, as expected, the indie space has managed to pick up the slack mainstream gaming left behind years ago. The recent Jazzpunk, which exposes players to a number of interactive and humorous vignettes, feels like a true achievement, as the only objective it presents is "find all of the jokes." And, to be honest, indies might be the next best place for funny games, simply because these developers have the ability to take risks. Humor, of course, always has a target, and if you're looking to sell a big-budget game to as many people as possible, you have to be accessible or inoffensive—or at least the right amount of offensive for the status quo.

Jazzpunk, on the other hand, feels like the future of comedy in games, as its humor isn't reliant on snappy dialogue, but rapid-fire, TIm and Eric-style gleeful absurdity. For comedy in games to stay relevant, we need more of these kinds of experiences than the ones we're used to: self-consciously "cool," catchphrase-spewing characters who get laughs through slapstick and random violence instead of creative weirdness. It isn't likely we'll see big-budget takes on the latter, but so long as creations like Jazzpunk exist, comedic games can be just as viable as they were in the days of interactive fiction.