The Tetris Effect

Some games have a habit of inserting themselves into your waking life; which ones have consumed you?

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

When you're deeply invested in something--a hobby, a project, perhaps a career--it refuses to confine itself to whatever corner of your life it naturally occupies. Games, obviously, are no different. As anyone reading this site likely knows, you can walk away from great games, but they still have a way of following you. It's like wearing a pair of glasses with a tiny Mario stencil rubbed onto the corner of one lens. No matter where you look: Games.

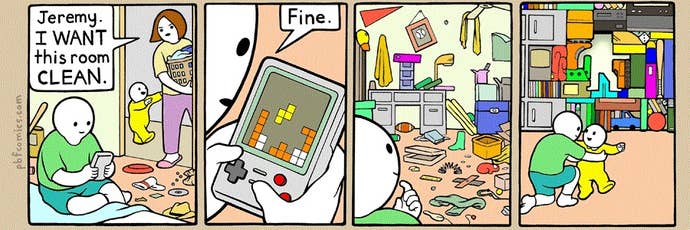

Maybe you spend the day struggling to focus, your thoughts returning time and again to which corner of Skyrim you plan to plunder next, which skills need building up. Maybe you go to a museum exhibit of classic Renaissance art and spend the entire time thinking about the AAA gaming industry. Or maybe you've experienced The Tetris Effect so-named for the phenomenon some people experience of playing the game for extended periods of time, and then continuing to imagine blocks falling or trying to mentally rearrange the real-world so items fit together neatly.

It's called The Tetris Effect, but it's certainly not limited to Tetris. It's either happened to all of us, with all manner of games, or I've done a poor job assessing my mental health for decades. Here are a few games that got their hooks in me. Leave some of yours in the comments. Or, you know, referrals to board-certified psychiatrists.

Catherine

Sometime in the post-Tomb Raider era, the thought of "block puzzles" in games got a (much deserved) bad reputation. They were the terrible bits that provide a change of pace from the all the fun you were having. But Catherine was essentially one big block puzzle, and it was brilliant. The game follows Vincent, a man whose fear of commitment is only matched by his fear of breaking things off with his long-term girlfriend. Those two contrary and controlling impulses give Vincent a bad case of insomnia, and what little sleep he gets is dominated by terrifying dreams where he must climb a giant tower of cubes, pushing and pulling a path upwards as he's chased by a nightmarish manifestation of his fears.

Where block puzzles are ordinarily tedious, simple, and slow, Catherine's were tense, complex, and fast-paced. The rules of when blocks would fall, how Vincent could climb along them, and what special properties certain blocks had combined to make a puzzle mechanic I could get better at understanding, but never completely master. The need to consider the block pushing several steps ahead was like anticipating moves in a game of chess. And just like in a game of chess, my understanding of what the board would look like grew helplessly fuzzy just a few moves ahead. As a result, I never internalized the entire system. I could never play on auto-pilot. I had to be focusing on the task at hand every step of the way.

That was fine while I was playing, but it quickly grew less fine when I stopped. Much like Vincent, I began to have trouble sleeping. When I closed my eyes at night, I would climb the blocks, plotting a way up the tower in my mind using the same rules and limitations in the game. This wasn't the first time I saw puzzle games when I closed my eyes (Tetris, Bust-a-Move), but it was the first time the core mechanic of the game was so complex that it kept my brain focused, which in turn kept me from getting to sleep. As miserable as it was working on half a night's sleep while I played through Catherine, it's still my favorite Tetris Effect experience of all time. Developers put players in the shoes of their games' protagonists all the time, but never had a game forced me to understand the main character's plight quite so literally.

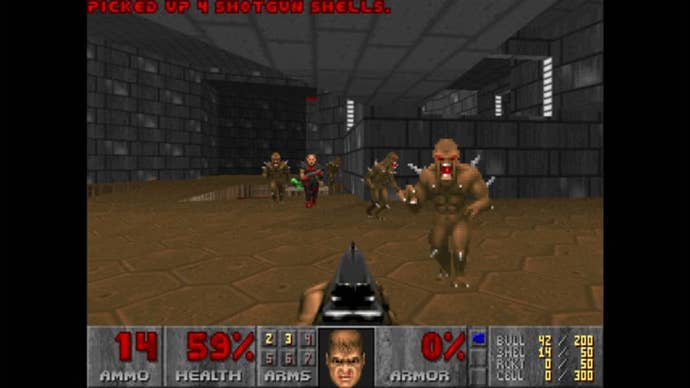

Doom / Tony Hawk's Pro Skater

When I was in high school, I had a friend who basically went through life assessing every environment's suitability as a Doom deathmatch map. Like all young Doom modders, he made a map of his school, a creative pursuit that could actually be shared with others in the pre-Columbine days. The thrill of playing these maps was in seeing the real world interpreted through a game, finding that the janitor's closet where the map maker groped his freshman year crush contained a health power-up, or that the football locker room held a dozen zombie jarheads.

The combination of two things I was familiar with from two different contexts to make something distinct commands a powerful fascination, like when you first heard that Johnny Cash covered Soundgarden and Nine Inch Nails, or that Heath Ledger was going to play the Joker. You might have expected it to be a car wreck. You might have expected it to be great. But if you cared at all about the disparate elements, you probably felt compelled to see it.

I liked Doom, but didn't instantly convert the world to shotgun pedestals and cacodemons, so I didn't quite understand how my pal saw the world. And I wouldn't until a few years later when I first tried Tony Hawk's Pro Skater on the Dreamcast. Instantly, my world became a giant skatepark. Where actual skateboarders might be impressed at kickflipping off a curb without breaking both legs, I started looking for opportunities to grind roofs and powerlines, planning out the exceedingly simple hops off a newspaper box and store awning that would get me where I wanted to go. I began to dislike picket fences, soft curbs, and other unskateable terrain for getting in the way of some otherwise awesome lines.

So when Tony Hawk's Pro Skater 3 gave me actual levels set in the places in which I'd already envisioned gleaming all manner of cubes (suburban developments, airports, downtown Los Angeles), it provided a personal apex for the series. Tony Hawk 4 continued the recontextualized good times with levels inspired by Chicago and San Francisco, but it was all Downhill Jam after that.

Grand Theft Auto III

This is the scariest one for me. I played Grand Theft Auto III constantly when it came out. One of my favorite things to do was just go on a rampage and see how high I could get my wanted level and how long I could last before Johnny Law brought my spree to a fiery (and usually fatal) halt. I actually became significantly better at this than at anything more directly related to finishing missions, and I started to optimize to that end. I looked for pockets of civilians to plow through, memorized where I could usually find unlocked police vehicles around Liberty City (crucial for free body armor and shotguns), and scouted rooftop locations to find new sniper roosts.

After a few weeks of heavy GTA III playing, I was driving along route 45 in the Chicago suburb of Grayslake when I spotted a group of maybe 10 pedestrians walking alongside the road. My first thought was, "I bet that would get me up to three stars just on its own," immediately followed by a sinking feeling in my gut, a cringing guilt as if I'd actually done something unforgivable. It's odd, because there wasn't any malice or bloodthirst behind the original thought. It was instead dispassionately optimized, which in some ways makes the whole scenario that much creepier. In a small but clear way, I had been desensitized to the notion of running people over with a car.

While it was unsettling to me at the time, I would find that same desensitizing effect of games actually work in my favor later in the winter when I hit a patch of ice and my car fishtailed. The thought that went through my head wasn't blind panic at the knowledge that I had lost control of a lethal amount of metal on city streets. It also wasn't "steer into the skid," or whatever they told me in driver's ed. It was, "Cool, this feels just like Daytona USA and Sega Rally," followed by a surprisingly level-headed and familiar regaining of control over the car. Thankfully, there were few other people dumb enough to be driving in those conditions, so there was no accident. But it was still a reminder that the games we play are powerful. They can affect us, the way we think, the way we see the world, and the way we react, both for good and for bad.

So what are your Tetris Effect stories? What games have sunk their claws that deeply into you? Let us know in the comments below!