The Real-World Problems Behind Persona 5

Behind every Palace of Persona 5, there’s a real-world scandal.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

This story contains spoilers regarding the game’s villains.

The first thing a player is confronted with in Persona 5 is a binding clause. “This story is a work of fiction,” it reads. “Similarities between characters or events to persons living or dead in your world are purely coincidental.”

The player is prompted to accept these terms before they’re allowed to progress. Agree, and the player is permitted to play the game. Refuse, and they’re booted back to the menu. Upon acceptance of the game’s fictionality and unraveling the game itself, it doesn’t feel like a coincidence at all. Persona 5 is a scathing look at issues so entrenched in Japanese society—from social dynamics, bullying, work culture, to nationalistic politics—that it’s impossible not to draw stark comparisons.

Persona 5 wasn’t always the heart-thieving romp that we know today. Initially, its sights were set farther than Japan, via an international backpacking trip. According to an interview with 4Gamer, director Katsura Hashino’s original plans for Persona 5 were purposefully different from the series’ predecessors, aiming to depict a journey of self-discovery away from home. But when the T?hoku earthquake hit in 2011, everything changed. “I felt that at once, my mood about Japan had changed as I rethought things,” Hashino said. “I wanted to refocus on Japan rather than direct my feelings to the outside world.” And so Persona 5 changed along with Japan. The designers and writers reoriented its initial coming-of-age journey, to bring the story back home.

“Persona 5 is unabashedly Japanese, going so far as to cover Japanese politics a bit,” Hashino told us in an interview recently. “Japanese genre fiction tends to deal with heroes fighting invaders from outside their society. In the west, however, these types of stories typically deal with outcasts within a society. [...] In the same vein, Persona 5 tells a story in which the heroes battle against villains risen from within their own society.” The villains Hashino speaks of may be familiar to those in Japan, whether experienced first-hand or through the lenses of the nightly news or other secondhand accounts: abusive teachers, yakuza, exploitative CEOs, corrupt police and government officials, and so on.

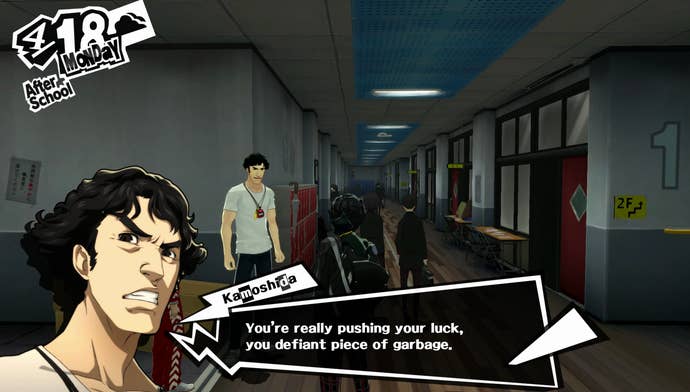

That notion was present in Persona 4 too, a murder mystery where the perpetrator was one of a small town’s own authoritative figures. Persona 5 runs the idea further with its local evildoers who rule over Palaces, themed dungeons that must be overtaken by a specific deadline. As the game progresses, the villains grow more malicious. Not just in the evil Shadow or bombastic Palace sense, but in terms of their positions of power as well. From a lecherous gym school teacher to a wildly corrupt politician, Persona 5 sets its critical sights far and wide—and no scandal in Japan is safe.

Persona 5 casts the player as a silent protagonist shamed by society at every turn for his criminal record. Our hero intervened in a streetside assault, but because the perpetrator was an intoxicated older (read: more important) man powerful enough to sue, the boy finds himself arrested, expelled, and carted off to Tokyo to the only school that will host him.

Everyone—and I mean everyone—in Persona 5 treats the protagonist with passing disgust. Our hero is treated as a nuisance, a troublemaker, a punk. No one cares that he helped a woman escape a skeezy assailant. Intervening in the lives of adults at all when he should have just “stayed out of it” is enough reason for them to turn up their noses. And when he quickly befriends Ryuji, another character slapped with a bad reputation, it feels like fate. Two good-natured kids shunned by society for a harsh event or two out of their control, left to their own vices. So, as JRPG kids do, they set off to save others from falling victim to the same.

“Everybody is just such a dick to you for having that criminal record,” said Thomas James, a freelance localizer with credits on Monster Hunter Generations and Tales of Berseria. James has lived in Japan in the past while attending college, and has repeatedly visited the country both before and after his time residing near Kansai. James played Persona 5 last fall in its native language: Japanese. “You don’t actually see [depictions of] bullying a whole lot within popular media [in Japan].” Bullying, especially in school and in the workplace, has remained a pervasive issue in Japan.

“Japanese as a language enables how it’s really easy to speak about people and things in passing, and force you to read between the lines,” he said. “So you can still sound polite and civil, but be really nasty.” In the localized version of Persona 5, which I played, the game’s subtle passive aggression is swapped for stark aggression, perhaps more in line with Westernized ideas of bullying. Where here, the game’s adult characters seemingly do their utmost not to spit on the main character at every turn.

Social Media Gives a Voice to Unrest, However Small

In Persona 5, social media is everything. From how the Phantom Thieves operate, to how word of their thievery and quote-unquote “good” deeds spread. Social media helps the Phantom Thieves find their next targets, and serves as an addiction for the teens. They can’t go a scene without their hands firmly planted on their phones, scrolling through messages, the Phan-Site for potential targets, or whatever else. “Whenever a political scandal occurs in Japan, people go crazy on social media sites,” director Hashino told USgamer. “I’ve seen data that suggests these sorts of tweets and posts are only made by a vocal minority, but considering how many people view them, their impact on society can’t be dismissed.”

Japan reached a tipping point after the Fukushima nuclear meltdown, a result of the T?hoku earthquake. Rather than citing safety risks immediately upon the nuclear incident, the Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO) hid the truth about the Fukushima nuclear meltdown from citizens for two months so as to temper public anxiety in the wake of the massive earthquake and tsunami. This led to the formation of movements protesting the use of nuclear energy in general—Twit No Nukes, a Twitter movement, in particular. But then the publicized unrest fizzled out, and society moved on quietly.

In 2015, the Shinzo Abe (Japan's current Prime Minister) administration circumvented typical procedures to amend the Article 9 clause in the constitution, the country's long-standing pacifist clause. The reinterpretation allowed the use of the Self-Defense Forces beyond Japan, causing an uproar in Japan. Or at least, a response far larger than Japan’s usual standards, seemingly jeopardizing the peaceful, war-forbidden society. In one protest, around 80,000 gathered outside of the Diet (Japan’s central government building in Tokyo). And among the unrest, rose a short-lived but salient movement.

The Student Emergency Action for Liberal Democracy, better known as SEALDS, formed in 2015 and disbanded last year. SEALDS was a widespread student activist organization dedicated to opposing the conservative policies of the government, starting with the reinterpretation of Article 9, and going beyond. And then they faded, citing failure as a reason. But their founder urged, it would not be the end.

“Even at [SEALDS’] peak, there was a lot of bad-mouthing them. ‘This isn't what a student should be doing,’ or ‘you're going to hurt your chances for future employment if you're on tv protesting,’ etcetera were the common arguments,” wrote Indiana-born Kyle McClain, a resident of Japan for over a decade, over email. “Things came to a head in 2011. People were protesting TEPCO. [...] There were parades through the middle of Shibuya of people demanding Japan get off nuclear power. And while there were sneers, slowly activism and protesting was starting to be accepted.”

While activism rose a very slight amount, its presence was still incredibly small compared to anything overseas, especially when in comparison to Western countries’ recent bouts of movements. “[SEALDS] disbanded one year after it was created,” Willy Miller, an English teacher in Japan who has lived there the past few years, wrote to me over email. Miller admitted that he had personally never even heard of SEALDS until our exchange, and had to look it up. “In comparison, look at [the] Black Lives Matter [movement]. It started in 2013 and is still going strong. There are many other political organizations that have been going for decades in America, and there is really nothing comparable in Japan, at least not on the same scale.”

For the average citizen, like Miller, having qualms with such issues hardly factor into daily lives beyond a passing observation. Local activist movements fail to garner widespread attention outside of the rare happenstance. The occasional larger protest only occurs around a timely scandal. As Miller told me, there’s a saying in Japanese culture that discourages speaking up against controversies. “[It’s] better to stay quiet [rather than] 'the nail that sticks up gets hammered down,'” wrote Miller. “So while a lot of people may not agree, a majority will not say anything.”

This bleeds into the perception of the Phantom Thieves themselves in Persona 5. Standing tall as vigilantes without a face to recognize them by, whose moral guidelines become skewed as the game progresses and their thirst for popularity sometimes clouds their better judgment. Then their popularity fades, and society moves on with their lives. Just as it does in reality. Except in the fantasy of Persona 5, they’re later outfitted to achieve a thing or two along the way. Save the world, save society, and return to a state of desired, freeing normalcy.

A Silenced Media

In the year 2013, the Abe administration passed the State Secrecy Law. The controversial law allows the government to withhold information of public duties which they deem as necessary to be secret, without any independent oversight (such as the necessary press). Whistleblowers and investigative journalists within Japan are thus faced with the potential punishment of imprisonment if they do in fact report on alleged unsavory happenings happening in their own country, a serious breach on the ethics of a free and fair press.

“While a lot of people may not agree, a majority will not say anything."

This was greatly opposed by the general population, but has since floundered in the public eye. Even as more scandals have taken hold and as leaders of movements pointed towards opposing the law moved onto other movements such as SEALDS. “The media changes topics quickly,” said Takayuki Machida, a resident of Japan who works in Administration, citing the often tabloidy focuses of the mass media. “The media should focus on more important things like economics [such as] taxes and protectionism, political gaffes that go nowhere and result in no actual punishments, and international relationships, [like with] Trump and North Korea.”

Karoshi: Death From Overwork

The fifth Palace in Persona 5 pits the player against a powerful CEO of a “black business” (a company that overworks their employees with unpaid overtime). The CEO thinks of his employees as slaves—as the game’s first boss, Kamoshida, did his students—and works them to the point of “karoshi,” the Japanese word for death by overworking. Karoshi is a term so established that it’s cited as a cause of death on official death certificates. During the Palace’s final boss fight, the CEO literally summons employees to fight on his behalf to the death. Some even explode at his behest, injuring teammates and killing themselves in the process. They are sacrificing themselves for the “company”—a literal manifestation of karoshi.

“The only [unrealistic] thing in that whole stretch of Persona 5 is that the big guy is so explicit talking about worker exploitation,” said James. “But otherwise, the particular nature of it, the whole imagery of these robot employees thrusting themselves into battle for the CEO and doing so knowing that they’ll probably die for the cause, but it’s okay because they’re doing good for the ‘company.’ That’s all very imbued in actual Japanese corporate culture.” In reality, black business CEOs aren’t the cackling, obvious villains we see in Persona 5 and other fiction. They’re subtle, and genuinely believe that overworking employees amounts to more work getting done, despite the opposite proving true according to data from the OECD about Japan’s low productivity, in contrast to working some of the longest hours.

McClain knows this issue all too well. “Young people are often corporate slaves. I say this because I was once one,” McClain said. “When you're out of college and start your first job, you are essentially robbed of your human rights. You are given basically poverty level wages, expected to work 14 hour days, and are not free to speak your mind. Corporate Japan is extremely hierarchical, and you are essentially forced to do things against your will. It is hazing to the next level.”

Karoshi—whether via heart attacks, strokes, or even suicide—is an epidemic in Japan. Recently, Prime Minister Abe has made attempts to “reform” the country’s work culture, by legitimizing a cap on overtime at 100 hours per month, and a yearly average of 80 hours per month. Activist Noriko Nakahara, whose physician husband’s cause of death was due to karoshi, told Bloomberg that the overtime cap is still absurdly high. “It’s totally unacceptable,” she said. “People are dying.” Of Japan’s entire workforce, 20 percent are at risk of karoshi, with drastically more citing stress from work in a more general sense.

“We’ll Take Japan Back.”

The game’s second-to-last Palace takes place on a massive cruise ship, as Tokyo sinks into the depths of the ocean around it. It’s the most daunting of all the Palaces. It’s the game’s Big Bad (before the surprise Big Bad, as Persona games tend to unravel) as we’ve seen him before, but here at his most unguarded and open. Shido, a candidate for Prime Minister, is the picture perfect politician outside of the Palace. He speaks in platitudes, inspiring voters with his vague speeches. When in reality, Shido is downright evil. Whether it’s murdering people to get his own political gain, manipulating those beneath him, or whatever else. When we see Shido envisioning an entire country as beings below him and his for the taking in a literal sense, it comes as no surprise.

During my conversation with James, he mentioned one particular piece of imagery in the Palace: an ominous campaign poster for Shido, half human, half Shadow. According to James’ own rough translation, it reads, “I'll exploit The People of Japan for all they're worth for my own ends.” In my playthrough of Persona 5’s localized version, this poster was lost on me. I struggled to remember trotting across it, likely because it wasn’t translated for English-speaking audiences. But even then, its resonance would likely be lost for those unknowing of campaign posters in Japan, and their known ambiguous promises.

In a follow-up email, James detailed why the particular poster took him aback, and encapsulated the political snark of Persona 5 as a whole. James sent me a poster of Prime Minister Abe’s while he was campaigning. The candidate stares upward, the image closing in on his face, as the text beside him reads, “We’ll take Japan back.”

“How empty a lot of these political posters are is what makes Shido's so potent."

“From what?” James asked. “The 20 year recession? Because certainly he doesn't mean the establishment because, as I mentioned, it's been the establishment party almost nonstop for 60-ish years in the Diet.” The poster is deliberately vague, but in Persona 5, it’s the opposite: it shows the malicious intent. “That's how empty a lot of these political posters are and what makes Shido's in Persona 5 so potent; it might only be taking place within the confines of his Palace, but it's much [more] explicit about his intent and views than those sorts of posters ever let on, and it speaks to how venomous a lot of those sorts of politicians like Abe and his cabinet are once they don't have to campaign on such ambiguity.”

Nobody’s Perfect

Persona 5 isn’t perfect in all the issues it vows to spotlight: in some, it even misses the mark entirely. Kamoshida’s abuse is never outright called out for what it is: rape. And Ann, suffering from the emotional distress of nearly losing her best friend to suicide and dodging an attack from Kamoshida himself, is almost immediately peer pressured by her fellow Phantom Thieves to strip nude to get inside knowledge on a new potential target when she doesn’t want to. The whole scenario is disappointingly played for laughs, and is deeply uncomfortable to witness.

Elsewhere, buried in the neon lights of Shinjuku or under the shining sun of the beach, gay men are seen as inherently predatory. And again, the scenarios are played up as a gag, spotlighting Ryuji’s uncomfortableness around them, as the grim “escape” music we’re used to within the confines of Palaces plays over the encounters. The developers have had less-than-great depictions of LGBTQ+ characters before (Persona 4’s Kanji and Catherine’s Erica immediately come to mind). However fleeting Persona 5’s visions of the particular minority community contrary to their past games, the depictions weigh heavier than ever. Especially in a game about fighting back against the oppressive expectations of a flawed society, to turn around and make fun of its gay characters is disappointing.

It’s also clear that the developers aren’t blissfully unaware of these issues, and in some cases are even capable of doing good. In Shinjuku, the player encounters and befriends Lala, a crossdressing bartender. Lala hires the protagonist when he’s in need of a gig (when in actuality, the hero needs to go undercover to investigate something). Lala says while the main character could crossdress if he wished, in Lala’s bar, it is not a requirement. Lala treats him with the utmost respect regardless of his decision, never guilting him into doing anything he wouldn’t want to do. Lala’s sweet, sassy, and most of all compassionate; the type of well-rounded human character that Atlus proved slightly they could do with Erica in Catherine before treating her coming out like a big joke. It’s just sometimes, Atlus opts for the broad stereotypes played for goofs approach, which makes the missteps feel all the more prominent. After all, Japan, like the U.S., is a society that is still slowly learning to accept immigrants and LGBTQ+ alike (even when there’s still a long way to go).

Even with its missteps, Persona 5’s trying to have a discussion with its highly specific audience: the country of Japan, and Japan alone. As Hashino himself told USgamer, Persona 5 is first and foremost a game made with a Japanese audience in mind, and nothing more. With that unique audience poses its challenges when it ventures beyond: the subtleties of history behind the homegrown villains in the game itself. “I joked around the time of the Japanese release that Atlus USA should just give out university textbooks as preorder bonuses,” said James. But hey, at the very least, we got an art book.