The Amy Hennig Interview: On What Changed With Uncharted 4, Leaving EA, and What's Next

At DICE Summit 2019, we catch up with one of the industry's most beloved writers and directors.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

Amy Hennig always speaks her mind. At the DICE Summit in Las Vegas, Nevada last week, the first thing that came to the former Uncharted and Legacy of Kain series director when asked about the development of Michael Jordan: Chaos in the Windy City in the early '90s was that "there was a lot of cocaine at EA during that time. I wasn't indulging in any of it."

She said this during an on-stage talk at the second day of DICE Summit with Double Fine founder Tim Schafer casually interviewing her, who also got started in the game industry around the same time. Their on-stage talk bounced around her career, with Schafer teasing the entire time that they'd eventually get to what Hennig is up to next.

It's been a big point of discussion since Hennig's highly publicized exit of EA in early 2018, following the dissolution of Visceral Games and the Star Wars single-player adventure game codenamed Ragtag, with Hennig behind it as creative director. The day after Hennig and Schafer's chat, Hennig and I had our own conversation in the eerily quiet press room in the early morning. With coffee at our side, Hennig again spoke her mind, just as she did on-stage just a day before.

USG: In your talk you mentioned that you went to San Francisco State, and that's where I went.

Amy Hennig: Oh yeah? I'm sure I was there long before you. [laughs] I was there, gosh it was only a couple of years. I didn't finish my masters, but I was there well until '91 because that's when I joined EA the first time. When I made the leap, you know.

Were you just kind of looking around for jobs while you were in grad school?

Well yeah, because it's expensive right? So I was taking all these little odd jobs in like word processing and desktop publishing, illustration for textbooks and manuals and things like that.

We were joking about it on stage [during the talk with Tim], but I just happened to run into a high school friend at a garage sale and he asked what I was doing, and I described it. I'd been studying animation a little bit and he went, "Hey, I got an idea. I was supposed to be the artist and designer for this Atari game. But I got to go to Texas and I can't do it. My buddy's the programmer, would you be interested in that gig?" And of course, I had always been a gamer, but like at the time I was just purely thinking dollar signs. I go, "Okay, how much will that pay and will it help me pay for school?" But it was just a serendipitous thing where by doing that job, I just sort of rediscovered my love of games. I was already doing that through my niece and nephew because I was playing with them, but having to pore over what people were doing in 8-bit like Nintendo and then trying to replicate that on the Atari 7800 [while developing Electrocop], I just, all those creative feelings of feeling like a pioneer all kind of came back. And I realized, wait a second, I think I want to do this instead of finishing my master's degree in film and becoming a filmmaker. So ironically it was like when I was in film school. What did you study?

I studied journalism, so same field I'm in now.

Yeah, well sure. I was sort of feeling I was getting the message that the kind of movies I wanted to make, my dream would be to make things like Indiana Jones and Star Wars. Right? But it was sort of like, oh no, you got to ratchet that back; dream smaller, you're not going to end up making that, especially as a woman. I got that message. This is in the '80s. And I saw this sort of sea of opportunity where all the rules weren't written both in terms of kind of gender hierarchy, but also just even the language of interactivity.

So the early days of games was reminding me of all the stuff I was learning and sort of film history and theory about the Lumière brothers and, you know, early, early film and George Méliès. And I felt like, here's all these people that were trying to figure it out, and that's where games were. So I kind of abandoned this other idea, and then the irony of course is I end up making games like Indiana Jones and Star Wars. I guess the universe points the direction you're supposed to go.

A Trailblazer for Women

And the big theme of this DICE is "Trailblazers," and you're a trailblazer not for just action games, but especially being a big woman figure in games. So what's that experience been like over the decades?

Well it's interesting. It's, man, it's such a minefield to talk about this stuff sometimes because everybody's got, I don't know, their own narrative. And like everybody's had such different experiences, so I'm always careful to say that when I speak about my experience, it's all I'm speaking about. I'm not denying anybody else's experience.

But for me—and I've talked about this a few years ago—games, even back in you know 1989, 1991 when I joined EA, that was my place of opportunity as a woman. Where I was feeling like those doors were going to be closed to me in film. So I take it really personally when people say that games are hostile to women. I'm like, well, that sure has not been my experience. And if I... look, backing up a second, people say, "Is there misogyny in the game industry?" It's like, well, of course, because the game industry is a subset of the world and there's misogyny in the world. We deal with it all the time, right? And is it worse? No.

And you know, I felt like because the rules were sort of unwritten that, for me anyway, it did feel like more of a meritocracy, so I felt like even though of course you run into people and you know they're probably being sexist or misogynistic. I just kind of write them off as assholes because it's like dwelling on whether they're—and obviously this comes from a place of privilege too, which I completely, readily admit—but like dwelling on whether they're engaging with you in that way almost gives them purchase. Whereas my attitude has always been you just sort of barrel right through that kind of resistance. And they're in your rearview mirror. And so I actually felt like, and I had a lot of male colleagues that actually advocated for me and, you know, contributed to my progression in my career which I'm so grateful for.

So I didn't have that experience, but I know other women have, and I think it just depends on the companies, people you're working with. So it's something that we just deal with in the world. And again, the way I counsel young women is just, you know, stick to your guns, trust your gut. Follow, pursue your dreams. Don't let anybody get in your way. Know your s**t. And generally that means that people can't get their hooks in you if they're trying to pull you down.

And you mentioned that when you were studying film you wanted to make a big action movies, which is definitely like a male dominated...

Yeah for sure, even now.

How'd the pitch go about for Uncharted, were you just like 'I want to make the Indiana Jones of video games' or?

It was more gradual than that. And like, obviously, I'm always careful to make sure that people realize that. We like this idea of there being auteurs, but that's just not reality in film or games. These things are made by teams of people and groups of people. And so, when I joined Naughty Dog, they'd already been sort of kicking around some ideas for what they wanted to do for the PlayStation 3. I joined the conversation and I couldn't even tell you exactly how it evolved because, again, it was just us "yes and-ing" each other.

We got to a place where we realized everyone else was kind of going a little grim and apocalyptic, and that certainly wasn't Naughty Dog's DNA anyway, right? We already knew that. You know, we really should be pushing more towards sort of like colorful and energy and optimism somewhat. And so, I'd always been a fan of the pulp adventure genre and the irony is that one of the reasons I ended up choosing to join Naughty Dog instead of staying at Crystal [Dynamics], was Eidos had just given Crystal the Lara Croft Tomb Raider franchise. I would have loved a shot at directing that, but I think they were so nervous—and I'd been directing the entire Soul Reaver: Legacy of Kain series for eight years. But I think they were so nervous about, this is at a time where the Tomb Raider franchise had sort of faltered and they were taking it away from Core [Design] and giving it to Crystal Dynamics, so I think they wanted to bring in a veteran director so I would have had to kind of step aside. I had already had a job offer from Naughty Dog, so I was like 'Okay, well that made my decision,' I guess. So I left and then made Uncharted. So. [laughs]

My brain and my sort of creative impulses already sort of lead me that direction. So you're asking how was that, being the only woman in that group and on that team. I didn't, I mean I just don't think about it. So sometimes I think maybe I'm a little oblivious—and I've had male friends in the industry tell me, "You know, don't be naive. I've seen it. You've received some misogynistic behavior." But I think my obliviousness is a little bit of actually a tool or technique, because like I said, it's harder for people then to get purchase because you don't engage, you're already just kind of barreling through. I never felt like it was ever difficult to pitch something like that to that group or to Sony. Honestly, I always felt respected as an equal. So I know that's not a good salacious story, but you know what I mean. I just haven't really had that kind of trouble.

But I think interestingly the hard part was actually getting people to understand that we wanted to do, this kind of unlikely relatable hero. I mean now it doesn't seem like such a weird pitch, but the idea of just doing this dude in a t-shirt and jeans and, you know, unremarkable is not a mascot character. And people had a lot of trouble with that at first. That it wasn't, that it wasn't iconic enough or whatever. But my feeling was, well, you know, having an actor on a movie poster wearing a t-shirt and jeans is fine, but we can't do that?

To me, that seemed like that was the mountain we needed to climb, that we could get to a place where we could create these actually believable, relatable characters. Not that there's anything wrong with sort of slightly more stylized, exaggerated mascots, but our whole thing was like, if we're going to try to come up with our own contemporary version of Indiana Jones, then he needs to have all those qualities of Harrison Ford in those movies. You know, he needs to be kind of flawed and vulnerable, and we always talked about how you need to be able to flinch from the bullets coming by. You needed to stumble when he's running around and all that kind of stuff. So, you know, you're not going to put him in a costume. He needs to be in a t-shirt and jeans. That defined all of our initial design and technical goals.

And you left Naughty Dog around the start of Uncharted 4's development…

I did about two years of development.

Oh, yeah. I think you've said in the past that you haven't played Uncharted 4.

I have now. I mean yeah, at the time, I think that somebody asked me, it wasn't long after the game had come out and it was like an interview for Rolling Stone or something, and I just said I hadn't. And sometimes—look it's hard. It's very weird when you create a thing and it's like those characters come out of your head and there's an intimacy to that. So it's weird for a while to look at somebody else's rendition of it, like it can be a little bit of a head trip. And it's hard to enjoy because of course it's kind of loaded, you know what I mean? But yeah, I mean, that's water under the bridge and I've since I've played it.

What were some ideas that you had for Uncharted 4 that didn't make it through?

Well, look, this whole spine of the thing in terms of what is the core historical mystery and the idea of this Henry Avery and this lost treasure, because we would try to start from what is that historical hook that we can then put a "what if" to. And there was lots of rumors around. I mean, there's a lot of romanticized rumors around that age of piracy, about where this money could have disappeared to and this idea of a pirate utopia which of course was probably just a fabrication or something that was certainly an exaggeration over some sandbar off of Madagascar or something. But we just thought well why not crank that to 11, right?

And just like in Uncharted 1, it was meant to be a little bit of a return to form. This idea that a lot of the story would be taking place on this undiscovered or forgotten pirate utopia island and that the detective story that we could weave through that. So all the beats, if you look at the chapter beats—with the exception of we didn't have the flashbacks to his childhood and then we didn't have the Nadine character—but just looking at the break by break that sorted the chapters, like where they go, what was happening, that was all while I was there.

And we were starting to work on like the, we wanted to add the rope mechanic, the grappling. So we thought, well, what a wonderful analog mechanic. We always loved the vines and the climbing and the swinging, like how about if we put that in his pocket? And then we were really keen on the idea of trying to figure out how to do the vehicles. It was just, it's a layout challenge because of course now you've just blown... you know, a vehicle you can stop and get out and look around any time, so the fidelity has to be amazing everywhere. It was a big challenge to solve. The guys were really into solving that.

So I mean, like I said the DNA, the DNA and the core story were all there. The major differences had to do with like, I was introducing the idea of Sam as the brother. But my take on it was sort of different, that it was a little bit more—I mean I wouldn't call him the antagonist in the classic sense, but it was an antagonistic force in Drake's life that he then had to reconcile. So it was, you know, complicated by stuff coming up from the past. So, it's a little bit different than him showing up and you know, "Hey bro, I got a problem." Then, of course there was an antagonistic element to Sam in the final version of U4, but it wasn't right there from the outset. So we kind of, in my story, it was a little bit more of the journey from this ghost from Drake's past being an antagonist to sort of reconciliation and reunification.

Opening Up About EA and Ragtag

And you're probably going to be asked a bunch about EA this week, obviously.

Yeah, right. [laughs]

Can you talk about any of your experiences at that role, or I guess the experience around when you left?

Well look, I mean it was a challenging time. I think everybody realized that because I think we, I don't know how public it was, but I mean we went through a studio reboot and, you know, had some reorgs and layoffs and the studio was entirely devoted, except for like just a handful of us at the beginning to working on Battlefield Hardline and then the DLC for Battlefield Hardline. So it was very hard to get to a point where we felt like we had the foundation we needed, the team size we needed, all the right disciplines we needed, until sort of late in the process. It wasn't like we were starting like right out the gun from when I started in April [2014]; it was very delayed. That gave us a lot of time though to sort of simmer on story and work with LucasFilm, which was great.

And look, I mean all I can say is the project was going along fine. And in terms of my experience from Naughty Dog, that's what people don't realize about game development too. It always looks like chaos until it doesn't, like it never looks like it's going to come together and then it does. And so, part of what's challenging about making games, especially in a sort of a larger organization, is how much of it is an act of faith and that kind of just letting go and not worrying about risk doesn't work on a spreadsheet, right? But risk mitigation can reduce a lot of greatness, because so much of what we do is going out on a limb and just taking like crazy risks. And then we ratchet back if it's like 'Well that didn't quite come together, let's, you know, we have a plan B.' But most of the time, you kind of go 'holy crap we did it.'

That was just kind of our reality at Naughty Dog because we didn't really have producers and overseers, where it was just like this kind of crazy ad hoc way of making a thing, which didn't translate well obviously to Electronic Arts. And that's fine because that has, you know, that's one end of the spectrum. It has some problems. Can result in sort of crunch and inefficiencies, but then the opposite end of the spectrum is so much of management and control and trying to get to certainty when what we do defies certainty.

So I think Visceral was sort of beset with a lot of challenges. Even so, we were making a game; people have said it was an Uncharted Star Wars. That's sort of reductive, but it's useful because people can kind of visualize something in their head. But what that meant is we obviously had to take the Frostbite Engine, because there was the internal initiative to make sure that everybody was on the same technology, but it was an engine that was made to do first-person shooters not third-person traversal cinematic games. So building all of that third-person platforming and climbing and cover taking and all that stuff into an engine that wasn't made to do that. We did a lot of foundational work that I think the teams are still benefiting from because it's a shared engine, but it's tough when you spend a lot of time doing foundational stuff but then don't get to go ta-da! [laughs] You know, here's the game.

I wish people could have seen more of it because it was a lot farther along than people ever got a glimpse of. And it was good, you know? But it just didn't make sense in EA's business plan, ultimately. Things changed over the course of that time I was there. So you know, what can you do.

And recently there have been reports that the game EA stemmed off Visceral's project was also canceled.

Yeah, I think that's been in the news. Yeah.

How did you feel when you heard that news?

I mean, terrible for the Vancouver team. I mean that group, they're a bunch of really nice, talented people, and they've been jerked around a lot, to be honest. I'm not trying to say that in any way that's sort of critical of anyone, it's just the reality of like, they've been shifted from project to project over the past few years. And I feel for them because they've poured their heart into one thing after another and then had it snatched away.

"It's tough when you spend a lot of time doing foundational stuff but then don't get to go ta-da! You know, here's the game."

I may not know if they're working on new stuff, and I'm sure they're resilient. So I'm sure they're kind of rolling with it, but everything I've heard secondhand was the stuff they were making was really cool. Very different from what we were doing, obviously being sort of an open-world experience is completely different, but everyone I've ever talked to informally said it was really, really cool. And it's really disappointing. Just like it was disappointing that Ragtag got canceled. So who knows, maybe those ideas will get resurrected. This is not like this stuff's getting erased, all that work is there. I would love to see what they were making just as I'd love to see people see what we were making.

What's on the Horizon

And since you've left EA, you've just been doing contract work?

Yeah, consulting and just sort of doing research and refueling the tank and having lots of meetings to kind of see what's going on out there. Just want to get a good feel for the landscape as things are really changing right now. That everybody is smart and well-meaning and everything out there, but you never know who's really going to be able to deliver on the thing because you need a number of partners to be able to create a game or to break into the space we're talking about. Which is to say, can we create the kind of narrative content that we know how to make, or I know how to make, but do it for a larger audience through these [technologies]?

If streaming real-time content is going to become a thing, I would love to be at the forefront of making content for that because it feels like a more natural place for traditional story content than the large games where it's a little harder to really tell a tight narrative, right?

So it's been good. I've never taken much time off between jobs, and it's been kind of from crunch to crunch generally. So to just take a breath and go, "No, not this time I don't need to jump." I can just take a year, explore new technologies, look into VR, take some gigs, meet some people, have some cool meetings, and just see where that kind of organically leads me.

And you mentioned yesterday you really liked Florence and Return of the Obra Dinn, these short indie games. Do you see yourself ever going in that direction?

Maybe. I mean, look, in all of these explorations there's a bunch of people I haven't talked to at all yet, like I haven't talked to anybody at Annapurna. That's kind of where I started is that. The indie space I find very attractive. I like the community of indie developers and how supportive they are, and the kind of all for one and one for all mentality I found very welcoming after leaving EA. It's still something I'm exploring.

I think part of the problem is I'm trying to figure out if I have a—I hate saying the word brand, it's gross—but like, if I have a wheelhouse, part of that is the fact that I know how to do like bang on photo real. Like the stuff we were doing for Star Wars, like high-end, high fidelity real-time content and believable characters. And it's probably too expensive for the indie space, so I think that if I were to do something in the indie space I would need to do something more stylized. And then I've just hesitated I think because it feels like maybe I'm abandoning one facet of my experience, which isn't the worst thing in the world, but I just want to be really thoughtful about—and I think I might have said this in yesterday's talk—but ideally the thing I point myself at is an overlap between experience and story and characters and creating worlds; experience in virtual production and real-time content creation and performance capture and the intersection of interactivity. Where that little venn diagram crosses, there's not a lot of people in the industry that can or have done all three of those things well. So abandoning any facet seems sort of not very bright on my part.

That doesn't mean it's not on the table. If I was going to go like, oh there's an opportunity to do this linear thing, but I love it and I'm going to go do it, and then I'm abandoning two whole facets of my experience. But if I was going to do something indie, if it was going to be more stylized and small, then I feel like I'm a little afraid that my knowledge and my expertise in the real-time virtual production space could kind of wither a little bit, get outdated. I feel like that would be a shame because I really enjoy trying to solve that problem.

A big focus in your talk yesterday was that you're trying reach a very mainstream audience now. Can you tell me a bit about what sort of avenues you're exploring for that?

Sure. This is early days, and there's people that probably that know a lot more about this than I do, but I searched over the course of the year looking at the landscape, and you've seen a lot of people announcing these real-time streaming services that they're working on. I mean in the last month or so I feel like there's been a whole bunch of announcements. I mean there's Google and Amazon and Microsoft and Apple and Verizon. I mean like everybody, right?

So this idea that we are now so accustomed to the idea that our music and TV and movies just sort of streams, you know, seamlessly right into our homes. I think it's inevitable that real-time content will do the same. That means we have an opportunity rather than just going, 'Okay, so it's like having a console but there's no console there, it's just streaming games right to your home.' If that still implies that the people that would be subscribing to that service are doing so because they're gamers, we're still missing out on this huge potential audience.

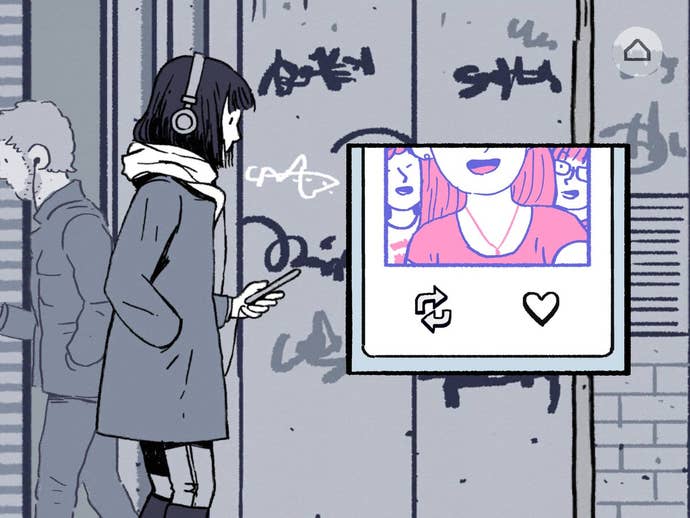

We look at games like Florence and Obra Dinn and [What Remains of] Edith Finch. These games are actually really accessible. Firewatch is another good example. Really, could be accessible to a much wider audience, but there's no discoverability for them. And it's all behind this very intimidating wall of hardware and controllers and things. So when I'm just looking at that and going, okay, if we believe that inevitably, we're going to have real-time data streaming right to our homes without having to buy any hardware. If we believe that we have this Trojan Horse device in our pockets, smartphones, that people have already learned how to interact with in an analog way, that could be our Trojan Horse controller into this system.

So there's a lot of ifs here right? Then it seems foolish to not be trying to figure out how we make interactive content for people that don't consider themselves gamers right now. And look, that's going to change, because those of us that grew up as gamers—I mean I was the 12-year-old kid that went to the arcade every weekend and I'm 54 now, right? And I'm still playing games and that's only going to get more true. I think there's a lot of people that are going to be aging with their hobby.

But then we also have to make sure that gaming doesn't become this sort of disenfranchising thing. And look, I'm not trying to be dogmatic about what games should and shouldn't be at all, because I hate when people do that. What I'm saying is that some of these open-world games or these sort of games as service, I mean especially when they are around competition and mastery or even the single player experiences, but maybe they go on for 40 hours. Like that's intimidating to people, even people that have been longtime gamers because it requires such a commitment. The interesting thing is, on one end of the spectrum you've got games getting longer and longer and longer or even endless, right? And on the linear media side you're seeing people in Hollywood figure out how they create even more bite-sized content. They're talking about five minute episodes, ten minute episodes, like how to get this sort of distracted culture, how we're creating content that's actually accessible and consumable for them.

So those two things don't jibe right? What we're doing by making these games bigger and more intimidating in that sense—and again, I'm not saying they shouldn't exist because people will jump on that—but what it's doing when we stop making some other games that are more finite and more accessible is some people that are longtime gamers are finding themselves a little alienated by their own hobby.

So I think there's an opportunity. We shouldn't be trying to pull mainstream folks that don't consider themselves gamers to the gamer world. I think that we need to go to where they are and figure out what it is that's appealing to them. And fundamentally as humans, story is appealing, right? So the idea that we could take what we know, an interactive narrative and crafting these things that already feel like you were playing a film or playing a TV show, and actually create them for an audience that would probably be very open to that if it was frictionless and discoverable for them. It seems like a worthwhile place to explore.

Is there anything else you want to say about what's next for you?

Oh gosh. I don't know, I've probably said enough. I mean, it all could change again. I know the last time I talked to people I was like really focused on VR and I did explore that for a while. I did a consulting gig with The Void for location based VR for a while. But my attention has kind of been pulled in another direction, it can be pulled back. So talk to me again in six months and we'll see. I promise nothing.