NES Creator Masayuki Uemura on the Birth of Nintendo's First Console

The man who designed Nintendo's revolutionary console recounts the system's birth and the challenges of building an international business.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

Originally published October 2015.

You wouldn't know by looking at Masayuki Uemura, mild-mannered engineer and professor, that he changed video games forever—or that his work set the standard for an industry that nearly died just as its was finding its legs.

Uemura's mild demeanor seems particularly remarkable coming from someone whose work not only reached into hundreds of millions of lives but also established the cornerstone for the video games industry as we know it today. In a medium whose loudest contributors are frequently egoists and rockstars who preen over having created a new iteration on someone else's established genre formula, it's a little surprising to find that one of the giants upon whose shoulders everyone else has stood for decades appears to possess so little ego or pretense.

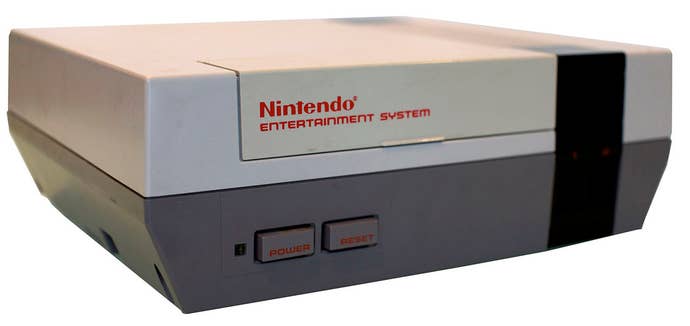

Surprising, yes, but welcome... and, more to the point, wholly appropriate. After all, Uemura didn't come up with just any old invention; he was the driving force behind the Nintendo Famicom, the system that came to America 30 years ago this month as the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES). He comes off as warm, approachable, and thoroughly good-natured, like most of the rest of Nintendo's core talent—only, perhaps, more so. His recent presentation at NYU's Games Center on the occasion of the NES's 30th anniversary (and the debut of an NES-centric exhibition at the Strong Museum of Play in Rochester, NY) was characterized by charming personal anecdotes and self-effacing humor.

In person, these traits come across even more clearly than in a public setting. I have no doubt that Uemura has fielded the same questions about the NES from thousands of young men and women who cut their teeth on one of the controllers he helped design, yet he fields them with more than mere grace: I saw a twinkle of genuine pleasure in his eyes as he addressed a room of college students, recounting his work designing what would become by far the best-selling game console of the 1980s. Rather than seeing lifelong NES fans digging for anecdotes as a nuisance, he indulges them all with the same pleasant grace.

Of course, unlike Nintendo's other pivotal designers, Uemura has the benefit of distance from his work. Being a decade older than the likes of Shigeru Miyamoto and Takashi Tezuka, he retired from the corporation years ago to become a professor at Ritsumeikan University in Kyoto. Uemura no longer has to worry about staying one step ahead of the competition, and queries about his older work don't get in the way of PR messaging about new games and consoles. Instead, he's able to connect with awestruck young adults who associate his work with endless hours of happy childhood memories. There are worse ways to spend a retirement.

A life's work

In a sense, Uemura sees the NES's 30th anniversary celebration as a capstone for his accomplishments.

"Honestly, today is going to be a really important memory for me," he told me shortly before presenting his lecture on the NES's development at the NYU Game Center. I had asked Uemura if he had any particularly fond memories of working on the Famicom. After thinking about it for a moment, though, he admitted that of all his recollections of working to create the console, coming to NYU meant the most to him.

"To tell you the truth," he told me, "development is a bit boring, actually, because if the thing that you’re making doesn’t sell well, you’re in trouble... and if it sells too well, you’re also in trouble." He chuckled. "You’ll get praise if you create something that sells really well, but it’s never going to please 100 percent of the people, and all those claims or complaints that people have end up coming back to the developer at some point.

"In a way, forgetting all of those things related to the development in the past, today has a bit of finality about it for me."

"Development is a bit boring, actually, because if the thing that you’re making doesn’t sell well, you’re in trouble... and if it sells too well, you’re also in trouble."

Uemura's philosophical response caught me off-guard, but perhaps it shouldn't have. Despite the warm humor with which he recounts the origins of the console, it's not hard to imagine that those must have been stressful times. Both the Famicom's birth and its transition to become the NES worked out against long odds and numerous setbacks. Later, he spoke of long hours fueled by free udon noodles—Nintendo paid for employees' meals when they worked overtime, and it sounds as though Uemura frequently worked late into the night on the system. And, of course, all of this happened the watchful eye of Hiroshi Yamauchi, the late, former president of Nintendo Corporation Ltd., famous for his demanding personality and exacting standards.

Certainly the feast-or-famine scenarios he mentioned loomed over the Famicom's birth. The Famicom project came about in large part because Nintendo's primary product at the time—the Game & Watch line of handheld LCD games—initially exploded in popularity, but sales soon began petering out. Yamauchi assigned Uemura to come up with a console based on interchangeable cartridges, one that would hopefully have longer legs than the dedicated game devices the company had been producing to that point.

Yamauchi set a target of one million hardware units sold of this new console; according to Uemura, it ultimately sold 14 million in Japan alone. And, as Uemura alluded to, even that success brought with it a unique set of challenges. The system became glutted with third-party software of questionable quality. Chip shortages delayed popular games. Nintendo, a small toy manufacturer with a handful of short-lived hits under their belt, wasn't really prepared for the sheer scale of Famicom's success around the world.

Yet Yamauchi's faith in Uemura paid off. In the end, he proved himself not only capable of leading the Famicom project, but uniquely capable. His history as an engineer, his design choices, and his personal relationships all helped steer a seemingly impossible project through hazards that likely would have undermined any other designer and resulted in a well-intended failure of a product.

For starters, Uemura already had extensive experience working on Nintendo game consoles. His first creations were a pair of Pong clones typical to the mid-’70s: The Color TV-Game 6 and Color TV-Game 15, which (as their names indicate) respectively featured six and 15 variants of video table tennis. Uemura ruefully admitted these products weren't particularly popular; there was no shortage of Pong-alikes by the time these devices made their debut (1977), and nothing about Nintendo's variants particularly stood out from countless other TV machines.

Rather, it was the company's next dedicated console—the Color TV-Game Block Kuzushi, or Breakout—that set the stage for the Famicom, in more ways than one.

Of all Nintendo's pre-Famicom television game systems, Block Kuzushi is the best known. The gently rounded console and its appealing display icons came about as the result of the work of a young artist named Shigeru Miyamoto: The future game design legend's first big project at Nintendo. However, according to Uemura, what shipped inside Block Kuzushi proved to be just as important to the company's future as the talent behind its graceful shell.

"In between the Television Game 6 and 15 and the Famicom, we made something in the block-breaking genre called 'Breakout,'" says Uemura. "With the Television Game-6 and 15 devices, I was the person in charge of development. However, we had purchased the chip sets from Mitsubishi. Nintendo kind of packaged them up and then brought them to the market.

"This was the step at which Nintendo started to learn, and which I started to learn the technology behind connecting a game system to a TV and having your images display on a TV. This allowed us to grab hold for the first time with this idea of using the television for something other than watching TV. That wasn’t really a concept people had in Japan at the time from both a technological perspective and also from a business perspective. We were kind of getting that idea out there."

"At the time, Atari was having great success with home games in America and we started wondering if this would be something we could do in Japan as well."

Having learned the ropes of console design by observing the work of Mitsubishi's designers on those early Pong clones, Uemura saw in Block Kuzushi a chance to take Nintendo's game development processes to the next step.

"At the time, in between the TV-Game 6 and 15 and the Famicom, the tabletop version of Atari's Breakout was very popular at arcades in Japan, and we got a lot of requests from people saying, 'Well, is this something that Nintendo could craft?' So all the engineers, including myself, set to work on making something that you could play in the home that would allow that same type of gameplay.

"[The chips for Block Kuzushi] were all made in-house. So, in that way, the engineers at Mitsubishi were teachers to us at Nintendo."

Having looked to Atari for inspiration on both the Pong-style TV-Game systems and the Breakout-like Block Kuzushi, Nintendo's engineers naturally began contemplating Atari's next big breakout: The Video Computer System, colloquially known as the 2600. The 2600 hadn't been the first console to feature interchangeable cartridges—that credit goes to the late Jerry Lawson and his Fairchild Channel F, which debuted a year before the 2600—but Atari's creation definitely established the market for ROM cassettes.

"At the time, Atari was having great success with home games in America and we started wondering if this would be something we could do in Japan as well," recalls Uemura. "We did think that with the 6, 15, and the Breakout game that we’d made, we established enough understanding among users in Japan that playing games on a television at home was something you could do."

Nintendo began serious research and development into their own standalone unit, but it wouldn't debut for another four years.