NES Creator Masayuki Uemura on the Birth of Nintendo's First Console

The man who designed Nintendo's revolutionary console recounts the system's birth and the challenges of building an international business.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

The console civil wars

Despite Uemura's critical role in the creation of Nintendo's early consoles—he served as the lead designer on every TV-based system the company produced up through the Super NES—he isn't the company's best-known engineer. That honor goes instead to Gunpei Yokoi, who most famously invented the Game Boy.

While Game Boy was by far the best-selling of all Yokoi's creations, it was hardly his only hit. In fact, during his long career at Nintendo, Yokoi oversaw only one true failure: 1995's Virtual Boy. He left the company soon after to establish his own company, Koto, which existed only a short while before Yokoi died in a tragic highway accident. Despite being killed at the relatively young age of 56, however, he left behind a remarkable legacy of gadgets and inventions, including most of Nintendo's early hit toys: The Ultra Hand; the Love Tester; the electromechanical versions of Duck Hunt and Wild Gunman that helped inspire the NES games; and most importantly, the Game & Watch.

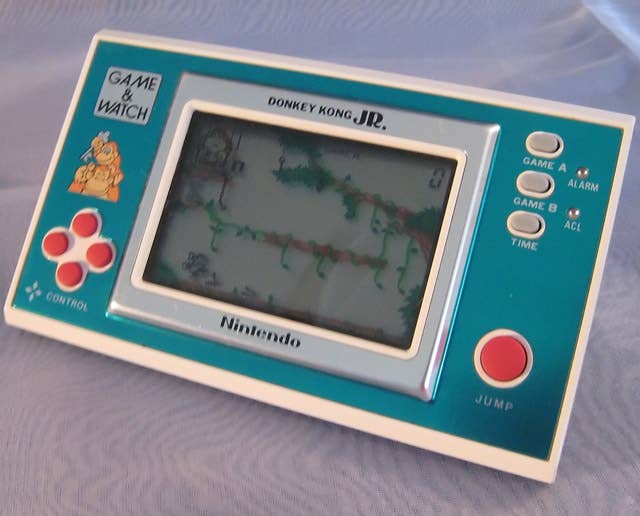

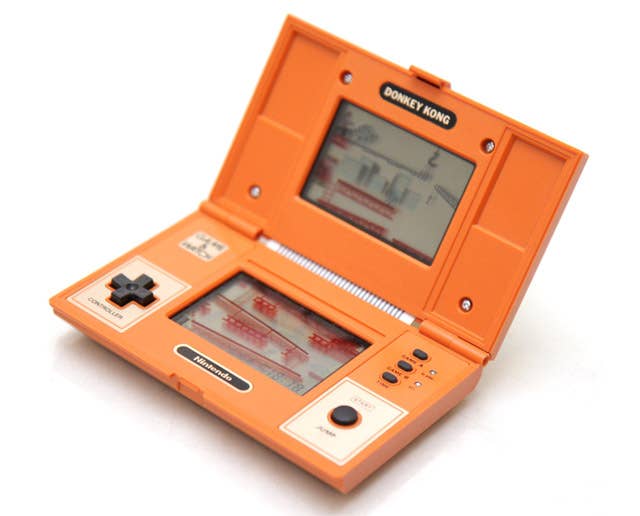

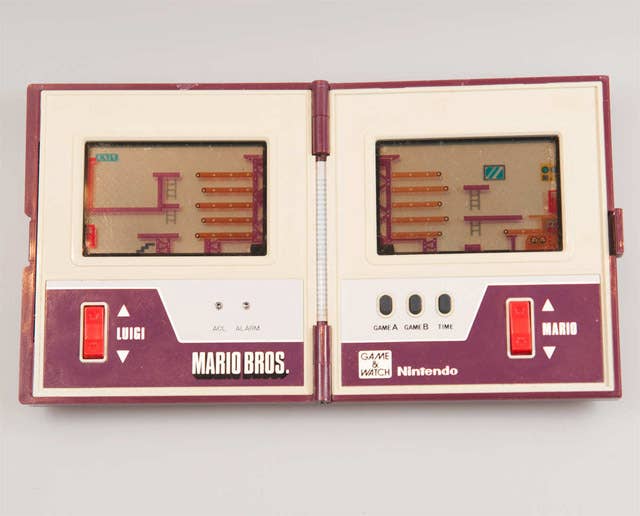

Uemura credits Yokoi's Game & Watch line as crucial influences for the Famicom hardware. The cross-pad controller that appeared on certain Game & Watch units ended up being a key element of the Famicom's appeal. Fittingly, given that the Famicom team's fundamental design goal was to be able to recreate Donkey Kong as faithfully to the arcade experience as possible, the cross-pad had debuted on the Donkey Kong dual-screen Game & Watch handheld. At first, however, the Famicom/Game & Watch relationship was a bit more frictional.

"At the time," says Uemura, "the engineers at Nintendo were kind of split between two teams: The one making games for arcade, like Space Invaders (which wasn’t ours, but we had Donkey Kong). And then there was Mr. Yokoi’s team, focused on making the handheld Game & Watch devices.

"The Game & Watches sold like hotcakes—it was surprising. I was kind of at my wits’ end and people were leaving my team to go to Mr. Yokoi’s team because there was such popularity around the Game & Watch. In the end, I was left with just three people on my team!

"It was at that time that Mr. Yamauchi contacted me and said, 'OK, let’s make a game console for the home.'"

While hardly as dire an internal conflict as, say, the famous Macintosh versus Lisa rivalry at Apple, the defections to the Game & Watch team left Uemura understaffed as he began researching and developing a suitable hardware solution. It was here that the Famicom team encountered its second stumbling block: Japan's semiconductor industry had run out of available microchips. In the first of what would prove to be many instances of the term "chip shortage" during the NES's life, Nintendo found itself at the bottom of a nationwide waiting list for processors, as all suitable manufacturing facilities were running full-steam to fulfill orders for PC companies as Japanese electronics giants like NEC began making inroads into the personal computing market.

"Manufacturing for all the semiconductor chips was tied up in home computers and other devices for other companies," says Uemura.

"We did have the previous experience with Donkey Kong [arcade machines], and we thought 'well, maybe there’s something we can do with that using LSI [large-scale integrated circuit, aka cartridge ROM] chips,' which would be more targeted for the home use. So this idea of having a system that was going to make use of LSI chip technology was going to be a theme that we decided from the beginning for our home console, but I understood how difficult this would be, having previously had to work on the Breakout game. And I knew that we would need to find a manufacturer—some sort of chip producer out there—could help us with this. Unfortunately, all of the makers who would produce chips like this at the time were really busy making chips for personal computers in Japan.

"There was just one company that had the latest equipment, and it was not manufacturing anything. So they were available and we were able to request help from them: Ricoh."

"Unfortunately, all of the makers who would produce chips like [we needed for Famicom] at the time were really busy making chips for personal computers in Japan."

Primarily known as a manufacturer of copiers and fax machines, Ricoh turned out to be the only company in Japan with facilities suitable for manufacturing and the bandwidth to handle Nintendo's request for hundreds of thousands of machines. The Ricoh connection would turn out to be fateful in many ways. For one, the manufacturer's engineers helped steer Uemura toward a chip based on MOS's 6502 for the Famicom—an uncommon piece of tech in Japan at the time—which fatefully brought future NCL president Satoru Iwata into Nintendo's orbit. Iwata had become a self-taught expert programming for the Commodore PET, which also used a 6502 chip. An expensive and hard-to-find computer in Japan, Iwata's expertise with the technology made him a tremendous asset for Nintendo in the early days: He helped Nintendo pitch the Famicom technology to Atari by programming four Famicom conversions of Atari arcade hits—a licensing attempt that, thankfully, collapsed when the 2600 market cratered—and later stepped in to help out with early first-party titles like Balloon Fight and Pinball.

In the more immediate term, the Ricoh connection turned out to be a blessing in disguise for more personal reasons. "As luck would have it," Uemura recalls, "the chief engineer of Ricoh was actually someone who had come over from Mitsubishi—he'd helped us make the TV-Game 6 and the 15. So I was able to rekindle this connection I had with my old teacher, in a way."

Japanese businesses, especially tradition-bound companies like Nintendo, run largely on relationships. Uemura's history with Ricoh's chief engineer likely had a sizable impact on the manufacturer's decision to commit its facilities to Famicom chip production. Without that connection, who can say if Ricoh would have partnered with Nintendo? It seems unlikely, given the surge of PC manufacturing sweeping Japan at the time, that Ricoh simply had a state-of-the-art manufacturing plant sitting around idle with no interest from other prospective PC manufacturers; far more likely is the prospect that the fortuitous personal connection between Uemura and his colleague gave Nintendo the edge over other applicants. That one stroke of serendipity may well have prevented the Famicom project from withering on the vine before it even began.

Muteki Mario

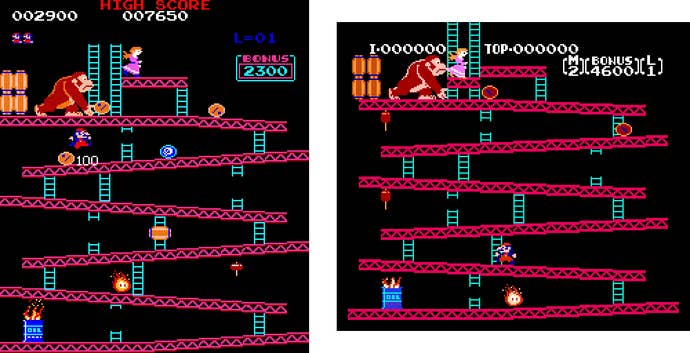

With the necessary resource to fabricate the Famicom secure, it then fell to Uemura to decide what form, precisely, the console would take. As Uemura explained during his NYU presentation, the primary goal for the system's performance specs would be to reproduce Donkey Kong as accurately as possible to the arcade version. (For more on this, please see Nathan Altice's excellent I Am Error, which details the challenges and compromises involved in Donkey Kong's arcade-to-Famicom conversion process.)

The Donkey Kong coin-op was still a hot new arcade hit at the time Nintendo initiated work on the Famicom hardware. The task of turning a top-of-the-line dedicated arcade board into a compact, interchangeable, and above all inexpensive cartridge must have seemed Herculean. Happily, though, this proved to be precisely the sort of monumental endeavor that Uemura's team and collaborators relished.

"Ricoh's engineers took this as a challenge," he says. "Fitting Donkey Kong into a LSI would be quite difficult, and they wanted to take this task for the sheer challenge.

"So we trusted [Ricoh] with this task of answering the question of, 'How are we going to convert Donkey Kong into something that can be played using this LSI technology?' Meanwhile, I took on this sort of overall question of, 'What will the system architecture end up being?'"

At this point, Uemura says, the attrition his group had suffered from engineers defecting to the Game & Watch team paid off in an unexpected way.

"There were, as you can probably imagine, a lot of difficulties we faced in doing things for the first time in building this hardware, but one of the most difficult was, 'What shape and layout will the controller have?'

"This has a touch of coincidence about it, too, but some of those people who had gone to work with Gunpei Yokoi’s team eventually found their way back to our team. So one of the ideas that came up because of that was, 'Well, we’ve got this Game & Watch multi-screen Donkey Kong that uses the controller format of a plus control pad and buttons.' So we hooked that up and got it working.

Uemura says his team experimented with several different controllers, including something closer in style to Atari's 2600 joystick. Yet none of them felt entirely comfortable. The 2600 design, for example, seemed too unstable for fast action games, and there were concerns that children might leave the controllers on the floor to be stepped on. Eventually, one of engineers who had worked with Yokoi's portable LCD games rigged a cross-pad plundered from a Game & Watch device to the Famicom for a trial run.

"At the time, we were prototyping various ideas for the Famicom hardware, as well as controllers," says Uemura. "When we took this idea that had been used for controls with the Donkey Kong Game & Watch and got it working on the Famicom prototype with that same style of controls, we immediately knew, 'OK, this feels right; there’s something good about this.' That means that there are actually a few people who can claim that they invented the controller for the Famicom!

"When we took this idea that had been used for controls with the Donkey Kong Game & Watch and got it working on the Famicom prototype with that same style of controls, we immediately knew, 'OK, this feels right; there’s something good about this.'"

"I think that the biggest reason that we liked the controls this way was just how good the original Game & Watch Donkey Kong, which was on multi-screen, felt. To expand on that a little further, with this prototype... the multi-screen format of the Donkey Kong Game & Watch means that you have a screen on top and a screen on the bottom, with the controls down below. When we hooked up the prototype, it meant that you were no longer looking down there [at the controls], but up here [at the screen]. Yet we suddenly realized, kind of mysteriously, that you didn’t need to look at the controls while you were playing the game, and it still felt right!

"And up to that point, we had tried a big variety of control styles and they had all had some sort of something that didn’t feel quite right about them, but this was something that no matter who tried it on our team, they could tell right away that this worked. So that’s when I decided to put my foot down and make the call that this is what we would be going with.

"I may have made the decision, but in the end, it’s something that whoever worked on the Game & Watch for Donkey Kong had a hand in, whoever brought the idea to try out the prototype had a hand in it—it was really a team effort."

While everything worked out for the Famicom hardware project, both inside and out, the controller's crosspad design doesn't come without some small regrets. "You know, we didn’t patent that technology at the time," admits Uemura, somewhat ruefully. "Once it was established, you kind of started to see it pop up everywhere, and now it’s kind of become a standard for controls in games."