"It Feels Like We Made 10 Games:" Kentucky Route Zero at the End of the Road

We talk with Cardboard Computer about the episodic structure of Kentucky Route Zero, Act 5's finale, and more.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

If there's any takeaway to be had about Kentucky Route Zero's nine-year-long development, it's these words by sound designer and composer Ben Babbitt: "Life goes on no matter what you're doing."

"To us, I think it feels like we made, you know, 10 games—five episodes and interludes and stuff," says Babbitt. "But it's all presented as this one game and, well, we're now so many years into being game developers or whatever, but externally it appears to be only one game. Just, there are a lot of little existential crises that I think come out of doing something for that long, doing one thing for so many years."

On the surface, Kentucky Route Zero is a bleak point-and-click adventure game with a magical realist atmosphere. Its influences span from Colossal Cave Adventure to Thomas Pynchon's paranoid postmodern classic The Crying of Lot 49, all the way to Robert Frost poetry. It is unafraid to reckon with the age-old American institution of lifelong debt and the dissolution of the American Dream, but it's also enchanting in how it portrays the mystical highway that lies underneath all of Kentucky. It's also, weirdly enough, unconcerned with most of that, or rather, only how it ties into the people who live through it. Kentucky Route Zero is a lot, all at once. And it's taken seven years—or nine, if you count its announcement on Kickstarter—for each part of it to be released to the world.

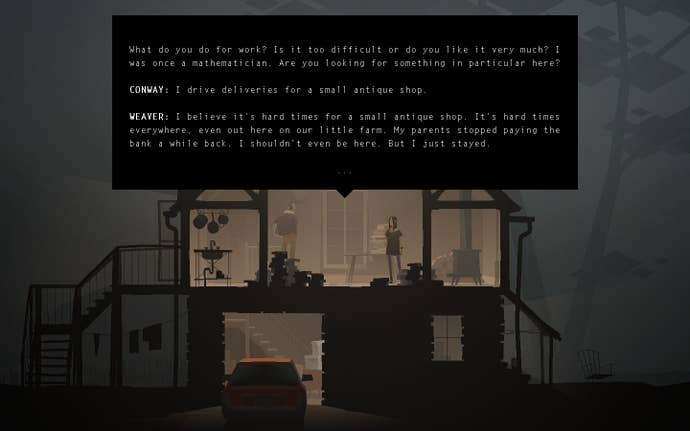

Kentucky Route Zero is the story of a tired man named Conway, and a woman who believes in ghosts named Shannon. In Act 1, Conway and his dog set out on one last delivery to 5 Dogwood Drive—an address he can't seem to find on any map. A man at a gas station tells him he has to take the Zero, a highway that seemingly doesn't even exist. In his hunt for Dogwood Drive, he meets TV repairwoman Shannon; Ezra, whose brother is a giant eagle; robot musicians Junebug and Johnny, and many others. Some join the party on their journey. Most don't. They all, as I wrote in my review, are united by homelessness as a result of some pitfall of debt. It's a thread that carries through each act; but more importantly, it's a game that feels like it was combed over its every detail. I suppose it's the result of a game that's been almost a decade years in the making.

It's a game that's always surprising. To wit, when Act 3 was released in 2014, what had been to that point a point-and-click adventure suddenly swerved into traditional text adventure territory. With the interlude "Here And Along the Echo," developers Cardboard Computer encouraged players to call a real-world hotline. In "The Entertainment," players could don a VR headset to watch an in-game stage production of two plays cobbled together. It was these bits, and much much more, that made Kentucky Route Zero resonate for the people who followed the series for close to a decade. They were what inspired leagues of fans to dial into hotlines; to read into any nugget of information that trickled out just in hopes of decoding when the next act would eventually come.

But in the beginning, it was very different. It had an almost-stop motion-like aesthetic; its characters were more intricately detailed, as seen in its original Kickstarter video. As mentioned above, Cardboard Computer consisted of just two people in those early days: Jake Elliott and Tamas Kemenczy.

The two had made small games in the past, but it was for Kentucky Route Zero that Elliott asked Kemenczy if he'd be interested in working on something bigger with him, leading him to take on what he refers to as his first "major video game." Kemenczy began as an art director, and together with Elliott worked to develop a crowdfunding pitch for their new project. "Basically where we started was with that Kickstarter video, and that's what set the tone and detail," says Kemenczy. "That's where I started working from, which ended up being a little bit too detailed and ambitious for our small team."

In 2011, the duo of Elliott and Kemenczy launched a Kickstarter campaign that amassed $8,583 of its humble $6,500 goal. As Kentucky Route Zero evolved, so did its vision, and now its art style couldn't be more different. While the vibe is all the same, it instead has a low-poly style akin to Éric Chahi's Another World. The style's stuck. Other indie games have been quite obviously influenced by it—or have just shared a common moodboard—ever since its arrival in 2013.

The project grew vastly in scope, brought aboard Babbitt in 2013, and quickly became a critical darling. In 2018, Cardboard Computer launched a Patreon to help fund Kentucky Route Zero's development. Recently, Annapurna Interactive partnered with the studio to help bring the game to consoles with its new TV Edition.

As the acts stretched on, so did the years between them. One year between Acts 2 and 3, two between 3 and 4, four years lodged for 4 and 5. And finally, Act 5 in 2020. The end of the road.

Paving the Zero

It's difficult to overstate Kentucky Route Zero's influence over the past decade. It's maybe the only episodic game to land on not just game of the year lists, but game of the decade lists before it was even "finished." Perhaps that celebration is indicative to the sometimes cruel fate that befalls most games now, where big or small, they're almost never "done." At least not in the way they used to be.

As development on Kentucky Route Zero continued to motor along, the gaming landscape shifted beneath it. When Kentucky Route Zero first began, it was the heyday of episodic games. Elliott even remembers playing the debut season of Telltale's The Walking Dead around that time, which debuted in 2012.

Elliott says he appreciated the opportunity to take things slowly, but that Kentucky Route Zero definitely had its challenges. "For me, the hardest part of it has just been that this project has always been there and needed work done on it for such a long period of time. It's been a really big commitment and it's been, at times, really difficult financially to make it work because there's only so many people that can play the game over the course of 10 years, or seven years that it's been for sale," he says. "Like at a certain point, people that are interested in it have it, and we still need to support the studio to finish it. So the money part is pretty complicated for selling stuff, I think. That's probably a big part of why it's not a popular model now, you know? Because of some high-profile difficulties people had making it work financially."

In recent years, episodic games have grown more and more unpopular, and in turn, unsustainable for developers. After lackluster sales for the episodic Hitman (2016), IO Interactive had its studio's funding pulled by publisher Square Enix. It later went independent and was able to retain the Hitman license, subsequently releasing the non-episodic Hitman 2 in 2018. In an interview last month with USgamer, the creative leads on Life Is Strange 2 reflected on the episodic sequel's underperformance. "[W]e knew that it wouldn't have the same huge success right from the beginning," co-director Michel Koch said at the time.

Most infamously, Telltale Games shuttered in 2018, laying off 90% of its workforce before letting go of the remaining skeleton crew in the months that followed. While some of its canceled projects have since found new life—The Walking Dead: The Final Season was finished under Skybound, and The Wolf Among Us 2 has been revived under the "new" Telltale—there's no denying that the episodic model has waned.

The episodic structure wasn't Kentucky Route Zero's only development challenge. "We'd often get excited about new potential ideas that we want to work out," says Kemenczy, "and that's—I mean I don't want to seem melodramatic—but it's heartbreaking to get excited about something and then know that like, you gotta kill that. You gotta get this out."

Spoiler Warning: Spoilers for the entirety of Kentucky Route Zero, including Act 5, follow. Proceed with caution.

In general, Kentucky Route Zero today has a lot more polish than it did as acts trickled out. It has a start menu with art and sound now, where its menu was once just white links on a blank page. The menus, Kemenczy says, were more or less an afterthought before this final release. The team was instead focused on the content in the game, rather than making a spiffy menu to dress up around it.

"Any opportunity we had to push work out of the way, we were taking it," Elliott adds. "Like when we first released Act 1, when you finish Act 1, the game would just quit itself. People were totally mystified, thought the game was crashing or something, but we were just like, okay, the game's over. We're done with you; it quits. And it was like, just for us, it's a very simple way to handle [the game ending] instead of making a page that we have to like wrap the player to or something like that. So, yeah, I think like Tamas said, [...] a lot of those recent changes that you're seeing in the TV Edition, and they're all in PC edition too, it just came from finally taking some of those things a little more seriously."

Looking back, many moments in Act 3 are seen as personal high points for the developers. It's an act that moves from a moving song by Junebug and Johnny that lifts the ceiling right off a bar—one of just a few instances of voice acting used in the entire game—to the aforementioned text adventure detour. The bar sequence even inspired Babbitt to make a whole album of Junebug and Johnny's music. First teased in 2016, the album has yet to be released.

"That was an impactful kind of creative moment for me," says Babbitt. "Just, you know, finding that voice and making the song for that scene and how it all felt when it came together and the way that people responded to it. It was really encouraging."

Kemenczy, for his part, found himself victim to his own clever ideas—ideas that were in turn hard to turn into a reality, but that he got dead set on regardless. One that he mentions in particular is a mechanic that appears only in Act 3, during a tour of the Hard Times distillery. It's here where a neon glowing skeleton shows Conway and Shannon around the whiskey distillery with enthusiasm and a tinge of doom as they drive a little shuttle through the small space.

"[B]uilding this point-and-click driving mechanic was... nonsense," says Kemenczy with a laugh. "I wish I did a better job of recording—now I have a good setup to just immediately record development, screen capture, video capture as I'm working, but at the time I wasn't thinking about that. There were such beautiful failures with that little shuttle in the early development. [...] Just as a side note, we've been very cagey because it's very narrative heavy, we didn't want to have any spoilers, but I think it'd be nice in the next process to be able to share more development stuff like that, sort of lighten the mood and make it less dredgery when you're fighting these complicated problems."

The Making of Act 5: "This Is Going to Be The Only Place"

Act 5 is the culmination of all of Cardboard Computer's work thus far. It's unlike anything we see in the first four acts, from how it all transpires in a single scene ("The Town"), to how it fully divorces us from the characters we've been directing this whole journey. Now, we're just the stowaway black cat; frolicking around, meowing affirmatively, and eavesdropping on our familiar companions as they decide what to do now that they've finished Conway's delivery to the weirdly vacant shape of a house on Dogwood Drive. Along the way, the cat even listens to the ghosts of past generations as they linger in town and share their histories.

The process of dividing the player away from the characters doesn't begin in Act 5 though. It starts back in Act 3 and 4, where at a smaller scale, we're torn away from Conway as he reckons with his imminent indentured servitude at Hard Times—the distillery that trades people's monetary debt for, well, their livelihood. He relapses into bad habits and isolates himself wholly in Act 4, much to the dismay of his earliest friend in the journey: Shannon. Helpless, we watch him unravel, and then he's carried away by the Hard Times skeletons without even a goodbye.

According to Kemenczy, the team had known where Kentucky Route Zero would end up from a very early point in development. "We knew going into Act 5 that they would be arriving at the town. This is going to be the only place, the only setting or major set piece or whatever for Act 5," says Kemenczy. And while the town, and its general landmarks—the drainage ditch, the well, 5 Dogwood Drive—were always in discussion, how the town would be laid out was much in flux.

Babbitt talks of how they discussed having a map, and even fast travel at one point, "because we want you to bounce around town all day." Traveling around town became the biggest design driving question: How do you efficiently traverse a town? That, apparently, is where the cat was quite literally dragged in. Felines are quick, and Cardboard Computer trains the camera to envelope the cat wherever you click to. You can dash up the hill to the tucked away graveyard, and the camera pulls back a tad to show you. You can skip to the center of the map where the stairwell everyone climbed up is, and the camera tightens a bit closer on the kitty.

And the cat is fast. Round and round you run, stopping to click through some ambient dialogue, or work through a micro text adventure with a ghost to learn about how the town was built up by corporations, and then swiftly abandoned without a care for the people who lived within it. The more you explore in the circle, the more new moments unlock. It unfolds so organically that I only realized by the end that—whoa—it really was all just one single scene, one lone level.

"So that sort of brought it back to the way that we treated the previous scenes, where it's more about singular space, using observational cinema," says Kemenczy. Act 5, in action, feels immediately similar to past scenes.

"[W]e have used this like circular camera, or this sort of orbiting camera behavior a couple of times before, like in [the interlude] 'Limits and Demonstrations' and then in the 'Hall of the Mountain King,'" says Elliott. "I feel like it's part of the vocabulary of the game, like the same way that some of the other camera frame works. There's the single Marquez Farmhouse Scene where the camera's just tracking inward the whole time, or tracking forward the whole time, or some other ones where the camera's just fixed. Through repetition, some of these different camera structures connect different scenes."

Act 3's "Hall of the Mountain King" connects with Act 5 in a big way: It's not just where we take a neat detour in Xanadu's text adventure, it's where we lose control of Conway's journey. Throughout the rest of Kentucky Route Zero, from a point most players might not even notice until it's too late, we only play as Conway's companions. And then in Act 5, we're suddenly none of them. "Act 5 is really about pushing that shift all the way," says Elliott. "So for me, I like to connect those two scenes just using the camera vocabulary as they're the same kind of moment."

While the end was always in mind, Kentucky Route Zero was still constantly evolving alongside its developers, who were, basically, growing up along with it.

"Things happen and life changes over nearly a decade," says Babbitt of Kentucky Route Zero's long development cycle. "And sometimes I found it difficult to feel like I was able to go with the flow of the things that were changing in my life while having to stay in this project. It took up a lot of time for all of us and was kind of the central thing in all of our lives in terms of our work and what we're spending our time doing. That was sometimes challenging to sort of feel like—and that's not to say that there wasn't room for change and progress, for the work to grow—[but] I think it did encompass a lot of individual creative evolutions in terms of our own work."

From the jump, Kentucky Route Zero was a game heavily inspired by the Great Recession of 2008 that plunged America's economy to the depths and left its most vulnerable citizens to suffer. Consequently, it never turned a blind eye to the darker side of its repercussions, for better or worse.

In Act 5, that changed. I wondered aloud to Kemenczy, Elliott, and Babbitt: Did the changing state of America affect the mood of Kentucky Route Zero for the better? Elliott, citing America's endemically screwed up history, and in turn, its history of radicals organizing to improve the general quality for their neighbors and families, says that for him, at least, his perspective over the last few years has turned more optimistic.

"The tonal growth in the game is also about—tonal growth sounds a lot like toenail growth, which is not what I'm trying to talk about—[...] but it has come, I think in part, reflecting on seeing what's happening now in America. Obviously things are really bad, but things have been bad for a long time. Like it's pretty much always. You look back at 100 years ago and see a lot of the same s**t going down; the same massive inequality of wealth and income, the same violence, suppression of organized labor by the state and corporate interest. It's a lot of the same stuff happening then," says Elliott.

"And also, with one movement that was during the development of the game, the Black Lives Matter movement sort of coalesced, and that's been a really inspirational movement, because it's people organizing, making really meaningful changes and acknowledging some of the evil that's happening now and not shying away from it, but really addressing it directly. Again, this is something the whole history of the United States has; there are radical actors working to try to fix things through the whole history and system. It's something I've been paying more attention to lately. So yeah, it's definitely a reflection of that."

In 2020, Cardboard Computer are finally ready to let go of Kentucky Route Zero, and move onto different projects. And move on with their lives, really. It's like they all hopped back onto the Zero and back into the real Kentucky, leaving Shannon, Junebug, and the rest of the crew behind in that abandoned town, just as the game lingers on that final shot of the group as one big semi-happy family.

Thus, the road for Kentucky Route Zero has ended. In fact, the trio of Cardboard Computer already have something new in the works. When I ask if it's episodic, they all laugh with a panicked, "no, no, no."

"Yeah, we don't want to do that again," says Babbitt, "or at least not now."