"Gritty" and "Mature" Aren't Synonyms

We saw quite a few games at E3 obviously shooting for adult audiences, but making something dark isn't the only way to be mature.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

At E3, we caught a glimpse of Crytek's upcoming next-gen title Ryse. In the demo Microsoft showed on stage, Ryse emerged into a Roman-era D-Day style scenario, with warships coming aground, soldiers spilling ashore and chaos all around.

Ryse ran forwards, ever onwards towards his eventual destination, and found his path continually blocked by those who would oppose him, each of whom wielded a prominent button prompt - like a target painted on their weak spots.

Press X to neck-stab. Press B for brutality. Press A for awesome.

The flurry of somewhat predictable violence continued throughout the vast majority of the demo, leaving me somewhat cold. War is hell, sure, and in Roman times, getting up close and personal with your adversaries was something of a necessity. But seeing this kind of darkness and violence doesn't make me feel like Ryse is a "mature" game. It leaves me feeling like it's an adolescent boy's power fantasy.

In my own free time, my personal gaming has been gradually drifting in an easterly direction as mainstream big-budget Western interactive media continues to do less and less for me. I've been delving primarily into the worlds of visual novels and the more obscure ends of the Japanese role-playing game market, and what I've discovered among those candy-colored, doe-eyed titles is something refreshing: maturity without overt, overwrought darkness or grittiness.

The protagonists aren't positioned as "magic bullets" who can solve the girls' problems single-handedly.

Let's take the series I'm currently playing through at the moment as an example: Gust's Ar Tonelico trilogy. Taken at face value, these three games are fairly conventional "band of plucky heroes saves the world" stories, albeit ones with some extremely well-realized lore. But that isn't really what they're about; instead, the main attraction of each of the three games is the dating sim-esque "Dive" mechanic, whereby the player character can enter the inner psychic worlds of his female companions and be there for them as they work their way through their numerous problems and anxieties, occasionally giving them a nudge in the right direction. In game terms, the more issues they've come to terms with, the higher their mental strength and, consequently, the more powerful magic they're able to use.

The stories told in these "Cosmosphere" sequences are simple and fairly understated, but they're handled extremely well. The protagonists aren't positioned as "magic bullets" who can solve the girls' problems single-handedly, but at the same time the games acknowledge the importance of personal intimacy and being able to confide in someone. They also touch on subject matter I don't remember ever seeing handled in a more mainstream Western game - or at least not in such a sensitive, understanding, non-judgemental manner.

For example, in Ar Tonelico Qoga, the third game in the series, it becomes apparent almost immediately that one of the game's two heroines has a problem with her self-esteem, believing herself to be worthless and useless. In her mental world, we see her constantly giving up "territory" in her mind to outside influences, until she's eventually left with almost nothing at all, and is prepared to simply fade away into oblivion. Through the love and support of the main character, she comes to recognize her own masochistic tendencies, along with the fact that she has inadvertently conditioned herself to feel a perverse degree of comfort from her misery and self-loathing - something that will doubtless be a familiar story to anyone who has ever suffered depression. In one particularly surprising scene, the protagonist is about to unlock her from some chains she has been bound in, but she asks him not to, saying that she feels safe in the chains, so long as the protagonist is the one holding them.

It's a surprising moment; not overly sexualized or fetishized, just simply and calmly stated as fact: this is what this character feels as a result of the things they have been through in their life.

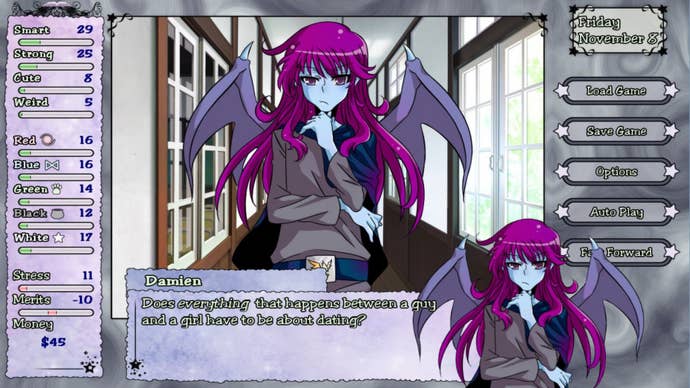

One of the paths through [Magical Diary] is an allegorical exploration of what it's like to be a woman in an abusive relationship.

Small, independent Western developers following the mold of Japanese games are likewise more willing to delve into territories often left untouched by the mainstream. I often cite Hanako Games' Magical Diary - a curious little visual novel/life sim/role-playing game/adventure hybrid - as an excellent example of this. In the case of Magical Diary, I was very surprised to gradually discover that, to my horror and fascination, one of the paths through the game was actually an allegorical exploration of what it's like to be a woman in an abusive relationship. This isn't made immediately clear to you when you start down that path; it gradually creeps up on you until you suddenly come to a realization that all is most certainly not well in the world

And yet Magical Diary manages to achieve this without being overly preachy, judgemental or obvious about it. Sure, the abusive partner in question is a demon, so in retrospect I perhaps shouldn't have been surprised how things turned out, but the preamble to the player character's relationship with him sets him up to be the brooding, misunderstood type rather than outright evil. Over time, we see the player character starting to make excuses for his increasingly erratic behavior and living in denial that he's actually a thoroughly unpleasant character. Eventually this all culminates in a horrifying scene that manages to act as a rape allegory without showing or saying anything graphic whatsoever; the interpretation is all in the player's mind, but by this point it will be very obvious to most players what the authorial intent behind this scene was.

This kind of thing is nothing unusual in visual novels, particularly those developed by Japanese outfits. While it's true that there are plenty of visual novels out there that are thinly-veiled excuses for some pornographic images of big-eyed anime girls with physically-improbable physiques, there's also a significant number that explore complex, mature themes other than violence that, in some cases, happen to incorporate sexual content as part of their narrative. Titles like School Days, Kira Kira and Kana Little Sister spring immediately to mind (to me, anyway!) as great examples of this type of game, exploring themes as diverse as the complexity of human relationships, coming of age, finding your true self, dealing with unavoidable tragedy and forbidden love.

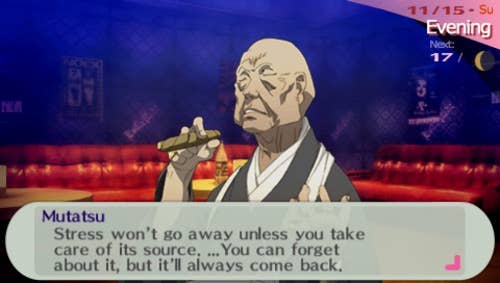

Somewhat closer to the mainstream, we have offerings like Atlus' excellent Persona series, which, with its third and fourth installments, decided to place as much emphasis on the main cast's "real lives" as on the parts where they were fighting Shadows and saving the world. The most interesting moments in the Persona series are not the parts where you're battling gigantic world-devouring beasts, they're the parts where you're hanging out with an old monk who hasn't seen his son in ages; the parts where you're comforting a man dying from a terminal illness; the parts where you're helping a party member deal with his sexuality and the image he puts across to everyone.

There's a market for these games, then, it seems. So why don't we see more mainstream Western studios attempting to tackle issues like this?

In many cases, it's quite simply a matter of fear, usually on the part of the publishers. Sexual content in particular runs the risk of seeing a game slapped with the dreaded "Adults Only" ESRB rating, meaning that many retailers will simply point-blank refuse to stock it - look what happened to Grand Theft Auto San Andreas following the "Hot Coffee" incident, for example, and that wasn't even particularly explicit. Alongside this, there's the ever-present need for triple-A publishers to make things bigger, better, more profitable, and in order to do that they need to appeal to as wide an audience as possible. The audience who enjoys nothing more than shooting people in the face over and over and over again is proven to be gigantic, so there's little reason for big publishers to take steps out of their comfort zone and tackle more mature themes with the risk of a smaller audience.

But the situation isn't as dire and grim as you might think. The success of titles such as Telltale's The Walking Dead proves that there most certainly is a place for more "human" mature games out there in the mainstream games business, and even stuff like the recent Tomb Raider reboot is a step in the right direction. With any luck, over time big developers and publishers will become more and more willing to accept that "gamers" as a group are far more diverse than just Call of Duty-loving kiddies. Perhaps then we'll start to see more genuinely "adult" titles that don't take the quick and easy route to perceived "maturity" by making everything brown and blood-splattered.

In the meantime, of course, there's a rich and diverse array of less well-known games out there that are willing to tackle complex sociological and psychological issues; you just have to know where to look for them. And, as I noted the other day, that place unfortunately isn't center-stage at E3... but seek a little harder, and ye shall find.