Exploring Game Boy's True Successor, Bandai WonderSwan

10 years after Game Boy revolutionized portable games, its creator took a swing at creating a faithful follow-up.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

In the annals of video game history, few things disappoint quite so much as a promising console that never quite takes off because of factors beyond mere quality.

Such is the case with WonderSwan, which stands out as one of the most tragic near-misses of our age. Launched 15 years ago, Bandai's first and only portable system holds a distinct place in history: It's the only console ever designed specifically for the purpose of taking on Nintendo directly. WonderSwan didn't simply compete with Nintendo, it incorporated Nintendo's own design philosophies.

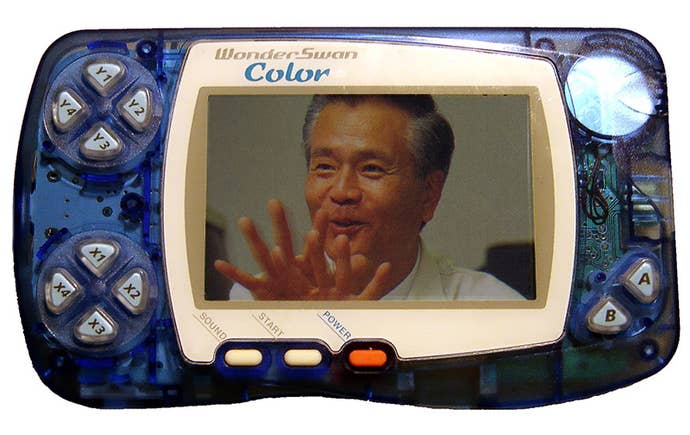

But of course it did. Its key creator was no less than Gunpei Yokoi, the man who had served as Nintendo's philosopher king of design for three decades. When he departed Nintendo, he took with him his belief that well-established hardware is a key to success, driving down costs while providing a familiar, well-documented, uncomplicated base for developers to work on. Nintendo itself lost sight of this mindset for a decade after Yokoi's departure; in that time, only WonderSwan upheld the tenets that had served Game Boy so well.

For Yokoi, WonderSwan also represented a return to basics after the colossal failure of his Virtual Boy project. The fallout from Virtual Boy prompted Yokoi to leave Nintendo and establish Koto, a small company dedicated to creating novel electronic gadgets. This included the WonderSwan, for which Bandai specifically approached Koto.

Watch Now: 10 Must-Play WonderSwan Games

Swan song

Sadly, by the time WonderSwan launched in March 1999, Yokoi was no longer around to see it. A highway accident in late 1997 resulted in his death. While the system's name was originally meant to refer to the hardware's gracefully curved lines, it acquired a dual meaning with Yokoi's passing: It became his swan song.

The connections between WonderSwan and Game Boy ran deep. At its debut, Bandai's handheld felt like a genuine successor to Nintendo's handheld, which at that point was a decade old. Despite seeing a few hardware refinements over the years, including Game Boy Pocket's clearer, more energy-efficient screen, Game Boy still ran on the same old '70s-vintage Z80 variant processor that it always had.

Key Player: Gunpei Yokoi

After his Virtual Boy project met with a dismal reception, Yokoi – one of modern Nintendo's founding fathers – left the company under a dark cloud and started his own business, creating more of the clever, inexpensive gadgets he excelled at inventing. Tragically, Yokoi died in a highway accident in 1997, making the WonderSwan project a sort of final monument to his brilliant creative mind.

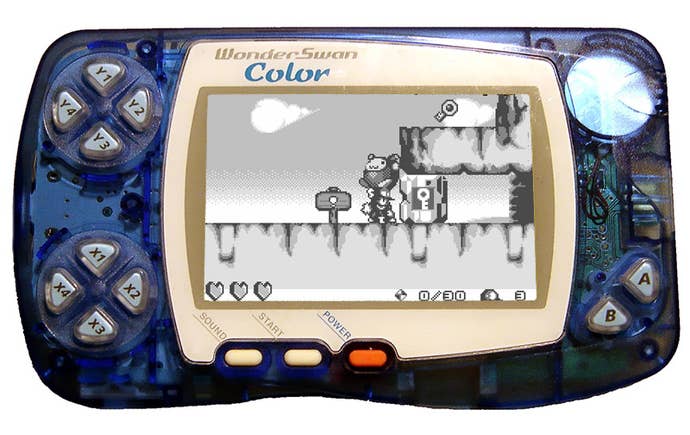

The WonderSwan, on the other hand, employed a more powerful 16-bit NEC V20 chip. And while it incorporated a black-and-white screen, its monochrome display wasn't limited to four shades of grey; it could display twice as many tones, which allowed for much more detailed graphics. And it was an absolute beast in terms of efficiency; while the Game Boy Pocket could run for 20 hours on a pair of AAA batteries, WonderSwan could squeeze as much as 40 hours from a single AA. And all of this for the incredibly reasonable price of ¥4800 – about $42 at the time.

In other words, it was inexpensive, it was capable, and it cost almost nothing to keep powered. It out Game Boy'd Game Boy in every respect.

Despite its low cost, the WonderSwan incorporated some forward-thinking features. It riffed on the ambidextrous design of Atari's Lynx by incorporating an extra set of directional buttons in the upper-left corner of the unit. While contemporary console design trends demand dual sticks for camera controls, WonderSwan employed a dual stick-like design for a different purpose: Players could rotate the system 90 degrees and play games in either landscape or portrait mode. While few games made effective use of this feature, it allowed players to play in "tate" (horizontal) mode for the handful of shoot-em-ups that graced the system (including the WonderSwan's most legendary release, the ultra-rare Judgment Silversword). It even had built-in memory for saving game data, which had the dual benefit of guaranteeing a password-free existence and keeping cartridge prices low.

Inexpensive, powerful, versatile – WonderSwan should have been the Game Boy's true successor. And yet in the end, despite seeing two upgraded variants in short order, the WonderSwan family sold less than four million units before its discontinuation in 2003. That puts it about on par, sales-wise, with classic would-be Game Boy rivals Lynx and Game Gear. WonderSwan seemingly had everything going for it; how could it crash so badly?

Key Player: Bandai

Bandai was no stranger to game hardware by the time WonderSwan launched; in fact, the system really represented a long-overdue entrée into the handheld market. From the Super Vision of the '70s to '90s machines like the Playdia and the Apple-branded Pippin platform, Bandai had plenty of experience in the first-party arena. But as with the company's other systems, WonderSwan couldn't rise above obscurity.

Out of touch, out of time

You can pin at least some of the blame for WonderSwan's rocky existence in part on poor timing. In the gap between the system's initial development (which would have begun no later than 1997) and its launch (March 1999), Nintendo changed the nature of the handheld market by releasing the Game Boy Color late in 1998.

In this sense, you can seen in WonderSwan a sort of inverse kindred spirit to Atari's Lynx. The Lynx launched after Game Boy despite a considerable development lead and was quickly humbled by its rival's, well, humility: The low cost, compact size, and modest battery requirements (as well as, let's be fair, the excellent library) of Game Boy made Lynx a tough sell despite its superior power. A decade later, the long-awaited color version of Game Boy (which included a considerable processor upgrade) made the WonderSwan a tough sell despite its superior price point. It just goes to show.

Key Player: Squaresoft

Square's allegiance with WonderSwan seemed less like a vote of confidence and more like a matter of laying in the bed they'd made. Square made an early foray into portable RPG design on Game Boy, but by the time the format really exploded thanks to Pokémon, the company had burned its bridges with Nintendo. With Game Boy no longer an avenue to easy portable profits, Square teamed up with Bandai instead. Once WonderSwan flamed out, though, an awful lot of those Square releases showed up on Game Boy Advance....

Another factor in Game Boy's favor, of course, was Pokémon. When Game Freak's monster-battling RPG debuted in 1995, it didn't turn many heads. But slowly, week by week, its sales didn't just hold steady – they increased. By the time WonderSwan launched, Pokémon had become a global success, with a heavily hyped, full-color, second-generation sequel on the way in late 1999. Enriched by the surprise long-term success of a single game, the Game Boy found its second wind right around the time WonderSwan launched. More games were released for the Game Boy family in 1999 and 2000 than in any years before or after. WonderSwan arrived at the peak of portable mania... but the market was already crowded.

Well, that was the case in Japan, anyway. Who knows how well WonderSwan might have fared if Bandai had looked beyond the boundaries of its home market? Yet WonderSwan remained a Japan-exclusive product for the entirety of its life, despite occasional reports of people spotting import units for sale at American retailers. No explanation for the system's failure to go international has been forthcoming through the years. Perhaps Bandai lacked the confidence or capital to go international. More likely, American retailers had no interest; given how hard it was to find Neo Geo Pocket systems and games at U.S. retail, it's hard to imagine they were clamoring for yet another niche portable from Japan.

Key Player: Banpresto

At the time of WonderSwan's run at the market, Banpresto wasn't yet a fully owned subsidiary of Bandai. But the two companies had much in common – that is, a raftload of anime licenses – and Banpresto's heavy support for the platform made for a decidedly anime-friendly library.

Quick reboot

Speaking of Neo Geo Pocket, Bandai clearly wasn't the only would-be Game Boy challenger to run afoul of Game Boy Color's surprise launch. SNK's handheld also launched in Japan around the same time... and like WonderSwan, it quickly failed due to its monochrome screen. And so both Bandai and SNK went immediately back to the drawing board to offer color versions of their systems.

While the original WonderSwan saw a remarkable amount of software support, its successor – the succinctly named WonderSwan Color – is where the platform truly came into its own. Third parties provided healthy support for the Color system, with several original WonderSwan Color titles (including Riviera: The Promised Land, several Final Fantasy remakes, and Mega Man Battle Chip Challenge) making their way not only to Game Boy Advance but also into English.

Despite the WonderSwan Color's enhanced capabilities – it could display far more colors than Game Boy Color on a much larger screen – the hardware still remained reasonably priced: ¥6800 (roughly $60) versus Game Boy Color's ¥8900 (approx. $78). Eventually, WonderSwan managed to capture nearly a tenth of the Japanese portable market: Respectable, but hardly a true challenge to Nintendo's dominance. Even the Color system's great original software couldn't begin to compete with the power of Game Boy – and, inexplicably, Bandai never made an effort to take a bite of that market. Even Neo Geo Pocket Color had a few efforts (such as the split-SKU Dive Alert and the collect-em-all BioMotor Unitron). You'd think the abundance of popular anime licenses in Bandai and partially owned subsidiary Banpresto's stable would have lent themselves to Pokémon clones (imagine catching 'em all in Super Robot Wars title), but no.

Key Player: Namco

While Namco has never been particularly shy about bringing its games to niche hardware, it went the extra mile for WonderSwan. Tragically (or perhaps hilariously?), the WonderSwan line's discontinuation was announced the same week that .hack//Infection (which made references to the extreme popularity of WonderSwan's successors) launched in the U.S. Nevertheless, the Bandai/Namco partnership surely helped pave the way for the Bandai/Namco corporate merger.

In the end, Bandai started out in an unenviable position that never got better. On the contrary, WonderSwan always found itself playing catch-up to Game Boy, first in terms of market share and color features, and later in terms of sheer power. A few years after Game Boy Color's debut, Nintendo leapfrogged WonderSwan Color's capabilities when it dusted off the nascent Project Atlantis and retooled it as Game Boy Advance. Bandai responded with the SwanCrystal, a slightly tweaked revision of the WonderSwan Color, but the writing was on the wall. Early in 2003, Bandai officially bowed out of the portable market (and hardware altogether), announcing the discontinuation of the WonderSwan line, leaving Game Boy once again the uncontested victor of portable gaming... at least until Sony announced its PlayStation Portable.

Summer of the 'Swans

Despite its short life and relatively modest performance – not to mention its isolation in the Japanese market – WonderSwan ultimately didn't do too badly for itself. It managed to outsell Neo Geo Pocket Color by a significant margin, performing about as well as Game Boy's earlier competitors in a much tougher market... and in only a single region.

Who knows how well WonderSwan could have performed in the U.S.? American gamers are notoriously tight-fisted (one might even say cheapskates), and the WonderSwan's economical design and pricing surely would have worked to its benefit. The system's heavy emphasis on licensed anime properties could have been a boon as well, given that the late '90s and the early part of the subsequent decade marked America's peak fascination with Japanese animation. On the other hand, the gently curved (read: feminine) design and quirky name would have needed some tweaking to appeal to us rugged Yankee nerds.

Key Player: Capcom

Like Namco, Capcom has never been shy about supporting hardware. While their investment in WonderSwan was less comprehensive than their Neo Geo Pocket support, they still brought some pretty great titles to the system. And some really bad ones...

Even with its short life, WonderSwan made a modest impact. Through either pop culture presence or licensing deals, it made cameos in random media, most notably as the host platform for "Fire Starter" in Gainax's FLCL. And thanks to open-ended products like the WonderBorg and WonderWitch, it became a favorite tool for hobbyist programmers. The WonderBorg was a small beetle-like robot that players could program via a WonderSwan cartridge, while the WonderWitch allowed users to create their own games (similar to Sony's Net Yarouze for PlayStation). The latter produced some of the system's most acclaimed software, including Judgment Silversword and Dicing Knight... which, incidentally, ranks among the rarest and most expensive software for any platform these days.

While WonderSwan ultimately will be remembered as a highly localized blip in the history of handheld games, as a platform it genuinely held its own. As the ultimate expression of Gunpei Yokoi's core engineering tenets, the system's obscurity resulted more from poor timing and Bandai's strangely meek strategy, not from any inherent flaws in the design of the machine itself. Handheld gaming fans owe it to themselves to track down one of these import-only gems and its top releases (conveniently outlined in the video above). In the end, WonderSwan may not have changed the world, but it makes a fitting capstone for the career of one of the most innovative engineers in gaming's history.