Donkey Kong Country Turns 25: Gaming's Biggest Bluff

Twenty-five years ago, Nintendo faced the threat of obsolescence with sheer bravado—and won.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

This article was originally published November 2014. We're running it again here to celebrate its 25th anniversary.

Ever since Mattel chose to sell the Intellivision platform by proclaiming its incredible graphical realism relative to Atari's 2600—our stick figures are better!—technology has been the gaming business' preferred battleground. But technology marches ever onward, and while this year's system may trump the competition with its jaw-dropping power, next year it'll be nothing more than a dusty relic. So it went for Nintendo, whose Super NES offered the slickest graphics and most convincing audio of the 16-bit era... right up until the point at which it didn't. By 1994, a mere three years after the console's American debut, the Super NES had grown long in the tooth, and enthusiasm began to wane.

All throughout the 16-bit era, Nintendo had managed to fend off threats to the monopoly it built in the '80s with great software and some ruthless business decisions. Sega made headway with its Genesis, but even that juggernaut couldn't quite dethrone Nintendo as the industry's big player. The looming specter of Sony's PlayStation, however, painted a different picture. Its awe-inspiring 3D capabilities were a far cry from the clunky visuals produced by limp also-rans Atari Jaguar and 3DO, and even early glimpses of the likes of Ridge Racer absolutely shamed the meager polygons Nintendo's FX chip produced.

Unfortunately, Nintendo's own Super NES successor, the Ultra 64, was still a year away from prime time (actually, as it turned out, two years). All the company had to combat the promise of PlayStation and Sega Saturn was an aging console and increasingly expensive add-on chips that couldn't begin to measure up to what the competition had in store. So Nintendo, a company that got its start as a playing card manufacturer, did what any card player would do with a losing hand: It bluffed.

Nintendo's bluff came in the form of Donkey Kong Country, a total reimagining of the franchise that had catapulted the company to the big leagues in the first place. It was a game a long time coming; outside of that summer's largely overlooked remake of the original arcade title for Game Boy, Donkey Kong hadn't featured in a new game since Donkey Kong 3 a decade prior. In fact, besides the occasional cameo in unrelated works and the mysterious Return of Donkey Kong for NES (announced but never shown), the former arcade superstar had all but vanished. Kong's disappearance was quite an ignominious twist for a character who had once been one of the medium's most recognizable faces.

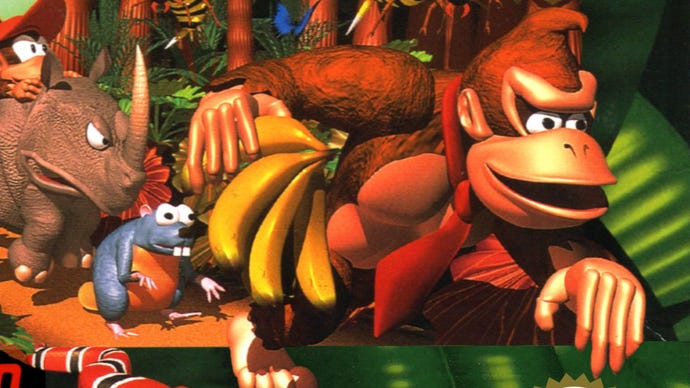

Perhaps Nintendo was simply holding him back for the right moment. Certainly DKC had profound impact. It brought back an '80s arcade staple in true '90s style: As the furry hero of a snarky platform action game. DKC was no mere Sonic clone, though. Not only did Kong have a valid claim on the genre despite his lengthy absence—the original Donkey Kong being one of the format's seminal works—the game was nothing short of astonishing from a visual perspective. Somehow, developer Rare managed to squeeze graphical fidelity from the wheezing Super NES that put the game's visuals on par with anything yet seen on more advanced hardware... and all without the use of one of those fancy add-on processors Nintendo was so fond of.

Of course, it was simply an illusion, a trick of clever graphical design. But what a trick! Rare fostered the perception that DKC was a game running on an advanced, 3D-capable system, despite the fact that under the hood DKC was arguably a step behind launch titles like Super Mario World and Super Castlevania IV. It eschewed the Super NES's built-in graphical modes, foregoing the platform's standard bag of gimmicks (rotation, transparencies, etc.) in favor of a game that impressed strictly with its basic visual design.

But that design really was impressive. Quibbles about the main character's radical '90s redesign aside, DKC banked on the public's general inexperience with 3D graphics to wow the masses with a game whose technological advancements happened entirely on the development side. There was nothing special under the hood of the DKC cart or the Super NES. Instead, Rare put cutting-edge computer techniques to use in the crafting of the game.

Never mind that DKC was, at heart, a fairly standard platformer. Kong and his sidekick Diddy could run and jump per usual, attack with an open-palmed ground slap, roll into foes like Sonic, and ride around on a variety of animal pals. There was really nothing about DKC that hadn't been done dozens of times before by dozens of other platformers, often in a much more fashion. But it didn't matter. DKC wasn't about revolutionizing the way games played; it was about convincing gamers not to trade in their Super Nintendo systems for something better. And it worked.

It worked because Nintendo and Rare's hunch was right. Most people didn't have real experience with true 3D game worlds in 1994, so DKC's fixed perspective didn't betray it as a relic of 16-bit hardware. When people thought of advanced computer graphics, they thought of the dinosaurs in Jurassic Park or the previews they'd seen of the upcoming Disney cartoon Toy Story. DKC looked much more like Buzz Lightyear than the boxy dominatrices of Toshinden did; in many ways, DKC's 3D fakery was better than actual 3D. Certainly it was more satisfying to look at.

DKC's design and legacy have left it open to considerable criticism over the years. The flimflammery of its visuals and the relative mundanity of its actual game design make it easy for critics to paint it as a classic case of style over substance. There's also the (seemingly apocryphal) claim that Donkey Kong creator Shigeru Miyamoto found DKC lackluster and amateurish, leading to the creation of the elaborately lo-fi Yoshi's Island as a reactionary piece.

But while those criticisms have some merit, they're not entirely fair, either. Sometimes, style is substance, and DKC is a masterful example of that axiom in action. This was no slapdash half-effort; Rare's designers didn't simply punch some numbers into a supercomputer and wait for the game to emerge fully formed from a slot on the side. On the contrary, DKC exudes craftsmanship. Rare went to great pains to create a consistent, seamless world that managed to convey trompe-l'oeil immersion despite being made of the same flat bitmap tiles that every other 2D platformer on the market used. This was no trivial matter, as countless games that attempted to borrow DKC's production techniques would prove: Few looked as clean or consistent as Rare's work, which committed to the illusion and pulled it off impeccably.

Before too long, actual 3D games would become commonplace, and "2.5D" platformers like Crystal Dynamics' Pandemonium! would expose the illusion upon which DKC was built. But in 1994, it didn't matter. Nintendo stood at the brink of obsolescence and made the biggest bluff in its century of existence. Incredibly, it worked. As Sony and Sega ushered in the 32-bit era, the creaky old Super NES enjoyed its strongest sales ever. Perhaps even more amazingly, people cared about Donkey Kong again for the first time in a decade. Not bad for a crazy handful of nothing.