Daily Classic: When Cinematic Games Put Gaming First, Arcades Gave Us Strider

Like a game and a movie (but more of a game).

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

"Hm, it is Strider Hiryu. He will never leave Eurasia alive!"

The Grandmaster's ominous vow, uttered with such confidence, comes immediately on the heels of Hiryu's assassination of Soviet Union's leadership, the earthbound puppets of the Grandmaster's global dominion. Here in some alternate reality version of the year A.D. 2048, the Soviet empire still stands, with its ruling body based in a heavily fortified city-fortress in Kazakh SSR. Top-ranked Strider agent has infiltrated the city and slain the nation's leaders, though this act of political assassination isn't nearly as shocking as the fact that the USSR appears to have been controlled by a team of cyborgs with the bizarre ability to link their bodies into some kind of mechanized centipede wielding a sickle and hammer as weapons.

Hiryu does eventually escape Eurasia by way of Siberia, though, alive and quite well. Not being the sort to take threats lightly, he takes the fight to the Grandmaster. His one-man war leads him to the Grandmaster's flying battle fortress Balrog, into the depths of the Amazon jungle, and eventually high above the planet where the despot rules from the space station Third Moon. And each and every step of Hiryu's journey is packed with the intensity of an action movie.

Games and Hollywood had been circling around one another throughout the '80s, but 1989 brought several meaningful breakthroughs. Games like Ninja Gaiden and Phantasy Star II integrated illustrated cut scenes throughout to help relay their respective stories. Phantasy Star's static images felt comic-like, while Ninja Gaiden added a touch of primitive animation to blur the boundary between manga and anime. Though imperfect — segregating action and narrative rather than fully integrating them — both offered a far more elegant solution than the medium's previous attempts to marry film and games. Unlike the full-motion video-based LaserDisk games precipitated by Dragon's Lair, they actually offered substance over mere flash.

Still, it was Strider's very different approach that more closely resembles what we see in movie-inspired games today. Strider largely skipped the cut scenes, using brief intermissions between stages to relay the story — ostensibly, anyway. The intermissions, with their rapid-fire imagery and sampled dialogue in a variety of languages, only made sense if you already knew the story of Strider. The plot is in no way self-evident from the cut scenes; fortunately, the game itself relays much of the narrative through its level and enemy design.

In fact, that was Strider's big deal. It played out like a highly compressed '80s action movie from start to finish. Unlike contemporary side-scrolling melee action games that sat alongside it in arcades — Rastan Saga, Rygar, the coin-op Ninja Gaiden, etc. — Strider wasn't content to simply do the "video game" thing and let players wander through repetitive stages of identical enemies. Each of Strider's five levels unfolded as a narrative journey through a "real" place, with varied architecture and a constant stream of new and different threats.

In the course of his journey, Hiryu would encounter an ever-changing variety of obstacles and enemies. Strider's level designs took the form of a string of set pieces, beginning with the infiltration of Kazakh's capital St. Petersburg and culminating in a showdown with the Grandmaster himself somewhere in low earth orbit. Along the way, the level designers constantly changed the rules so that each portion of the adventure remained memorable. Now, not only did the level themes themselves create a sense of progression (a trick Capcom had helped pioneer for arcade adventures with 1985's Ghosts 'N Goblins), but within each stage players encountered numerous changes in theme and tons of unique situations.

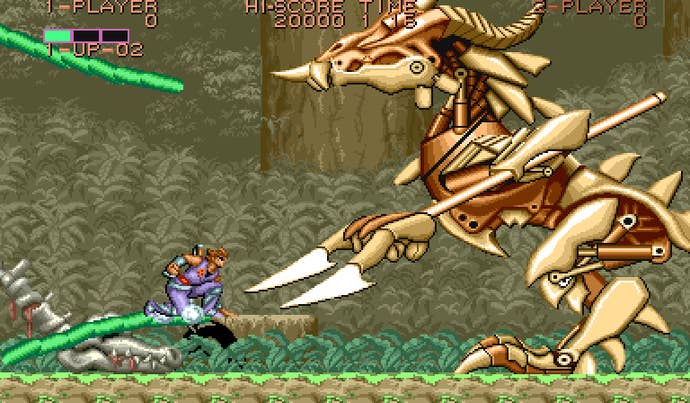

And so, the first level didn't simply see Hiryu rushing to destroy the Grandmasters cyborg puppet Politburo; it saw him gliding by stealth into the city, climbing over onion domes and anti-air weapon emplacements alike, facing off against a drug-enhanced super soldier, and dismantling a laser defense system along the way to the fight. His escape from Eurasia took him through icy wastes, where he dealt with a giant robotic gorilla, outraced an exploding minefield, scaled the scaffolding of a power station, and fought a flying bounty hunter. And so it went, with a constant stream of surprising threats — a troupe of Chinese martial artists, a herd of dinosaurs, even an antigravity device that changed the actual physics of play — keeping players on guard at all times.

The designers of Strider Hiryu (most notably director Kouichi "Isuke" Yotsui) poured a preposterous amount of detail into the game. Observant players may often have noticed completely incidental events happening outside of their own sphere of influence, such as the captain of the Balrog fighting off low-level minions trying to make their way to his personal escape pod as the battleship self-destructed. Each major encounter was framed as an event. For example, you didn't simply fight the Soviet super-soldier; when you entered his chamber, he flexed his muscles so hard that his shirt shredded to pieces and the machine pumping enhancement drugs into his system exploded. You didn't merely go toe-to-toe against a giant mechanical T-rex in the Amazon; you approached it on the back of a brontosaur, which disintegrated into ash and bone when the robot monstrosity blasted it with a gout of flame. Hardcore.

What makes Strider truly great is that throughout all of this, the game always came first. Most of these cinematic and peripheral events transpired as you play, or else they took over the action for only a fleeting instant to provide a moment's set-up. Strider never made too much of a show of its spectacle, allowing its wild twists and turns to play out as part of the game. The result was a two-hour action blockbuster movie compressed into 30 minutes of breakneck gameplay. There were no quick-time events, no trash-talking pre-fight cut scenes, no lengthy follow-up dialogue after unique battles.

The downside to this was that Strider possessed depth and nuance that players never noticed. The strongman in Kazakh used a number of unique techniques against Strider, including the ability to grasp him and fling him against the wall, but you could destroy him before he ever had a chance to employ this attack — and as soon as you defeated him, his chamber collapsed in flames, forcing you to scramble for cover. The trio of acrobat sisters who guarded the bridge of the Balrog each had her own unique combat style, but if you simply barrelled in with your sword swinging, you may never have seen those forms demonstrated. There was never a moment to stop and muse as you led Strider Hiryu to his showdown with the Grandmaster; you had a world to save and crazy mechanical abominations to dismantle.

While Strider's breathless approach undoubtedly came as a result of its arcade origins — where it's all well and good for a game to look cool, but the local operator expects it to move things along to earn its next quarter drop posthaste — it also demonstrated a profound sense of confidence on behalf of the designers. Rather than force the player to gaze in wonder at their clever design, Isuke and his team left those insane details as Easter eggs or simply quirks that might unfold through repeated play.

And really, who wouldn't want to replay Strider? It was a visual tour-de-force in 1989, with some of the best visuals ever seen in a video game. The music (if you could hear it amidst the din of your local arcade) smoothly segued from one theme to another in unison with the setting of the action. Hiryu himself controlled perfectly, offering a huge array of skills activated via simple, distinct inputs. It was a perfect combination of play and spectacle, but its creators never lost sight of the fact that it was a game first and foremost. How often did that happen back then -- or now, for that matter?