Daily Classic: How Clash at Demonhead's NES Comedy Defied Whitewashing

A stony-faced Trojan Horse of a game unleashed subversive goofiness upon unsuspecting players.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

To judge Clash at Demonhead by its cover, you'd expect it to be your typical low-budget, 1980s, post-Flash-Gordon, sci-fi schlock: A muscular Rambo-looking dude in chromed armor fires lasers at an insectile skeleton-man and other strange monsters while what appears to be a space cheerleader shrinks timidly into his protective embrace. Real boilerplate, potboiler stuff.

And that is precisely why that old saw about judging works by their covers exists in the first place. Although the box of Clash at Demonhead actually does depict concepts from the game (the chrome guy is protagonist Billy "Bang" Blitz, the skeleton is apparent villain Tom Guycot, the mountain in the background is the locale in which the game action takes place), the in-game presentation couldn't be further from the straight-to-video, Mystery Science Theater 3000-fodder quality of the cover's airbrush job. If the box art begged to be splashed across the side of a stoner's van circa 1980, the in-game aesthetic would have been better suited a wall scroll at a mall kiosk a couple of decades later. It was 100% pure anime... a word most American gamers didn't even know at the time.

In a recent piece on Medium, Henk Rogers (the man who brought Tetris to the West and role-playing games to the East) discussed how his Wizardry-inspired Japan-only creation, The Black Onyx, presented itself to Japan with box art in the style of Frank Frazetta: "A hero standing on a pile of monsters swinging a sword. The problem was that in Japan nobody knew what the hell that meant," he recalled. Within a few years, sales of The Black Onyx were eclipsed by the likes of Dragon Quest and Final Fantasy. Rogers admitted, "I realized that I didn’t quite understand the Japanese aesthetic and way. These games were quite different to mine, and just struck a more effective cultural chord."

Dragon Quest, of course, became a blow-out hit in Japan in large part because of its illustrations and character designs by Akira Toriyama, the cartoonist behind popular manga series Dr. Slump and Dragon Ball. The game didn't attract much attention until publisher Enix began promoting it in the pages of Shounen Jump, the weekly comic anthology where Toriyama's work appeared. Suddenly millions of kids took notice. The whimsy of Toriyama's illustrations didn't translate well to the game's miserable little map sprites, but once battle began players got to go mano-a-mano against colorful monsters straight from the pages of Toriyama's comics. And Dragon Quest was hardly unique; Japanese-developed games had drawn visual inspiration from manga and anime for as long as Japanese designers had been making games.

But Toriyama-style cartoons were as anathema to American audiences as Frazetta-esque fantasy paintings were to the Japanese. A cultural divide was at work, which made things difficult for Japanese publishers who hoped to peddle their distinctly Japanese-flavored video games in the U.S. as the '90s rolled around. In those days, anime in the West was confined to a small, fanatical group of animation connoisseurs. Anime would make inroads in the States before long thanks to the likes of Akira and Sailor Moon, but at the start of the '90s a video game publisher would sooner turn a box into an eyesore of bad art and inscrutable design than dare leave Japanese cartoons on the cover.

While cover art was easy to change, in-game visuals were a different matter altogether. Try as they might to scrub away any vestige of a foreign origin (especially a Japanese origin), publishers usually (but not always) found it easier just to make the cover more Western in style and leave the in-game contents untouched. Maybe they'd reprogram a rice ball to look like a hamburger; perhaps they'd change some names around; but ultimately they'd leave the distinctly Japanese aesthetic untouched.

Which brings us back to Clash at Demonhead, a textbook example of this phenomenon in action. By no means was Clash the first game whose origins its American publisher tried to half-heartedly whitewash, and it certainly wasn't the last, but it may well have been the most obvious.

Clash at Demonhead was not based on an existing animation or comic. Its Japanese title, Dengeki Big Bang!, doesn't correspond to any other property -- not even Media Works' Dengeki family of game and anime magazines, which began publishing a few years after Clash's release. But you'd never know it to look at the game; every inch of it is drenched in manga aesthetics. It feels completely like an authentic licensed property.

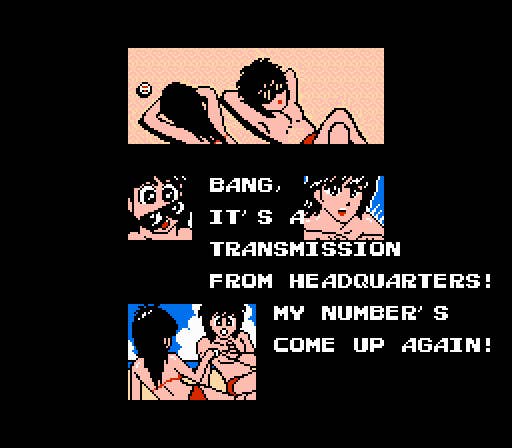

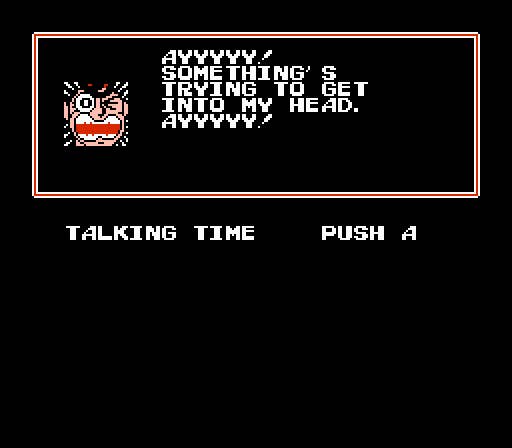

The game begins with comic panel-like story sequences in which Bang, an agent of a secret organization called S.A.B.R.E., is summoned from his vacation to rescue an abducted professor. Bang himself is a young hero in the '70s action anime mode, with big hair and distinguishing facial scars a la Harlock, and a can-do spirit of the type that would later be lampooned by more self-aware post-Evangelion anime like Martian Successor Nadesico. But more importantly, Clash perpetually bordered on complete zaniness, slipping freely between dramatic action and goofy pratfalls in the manner of true Osamu Tezuka devotees.

A surface reading of Clash at Demonhead might suggest a game that played like a more fanciful version of a James Bond spy tale, with the quest for a lost professor leading to a race to deactivate a planet-shattering doomsday device. Aside from the fact that Bang's nemeses took the form of bizarre, inhuman creatures (besides the skeletal Guycot, Bang also battled a raging panda, a mushroom person, and more), Clash's plot fell very much into the epic secret agent mold. Yet its whimsical, anime-influenced presentation took the edge off the drama, rendering it very much as a broad comedy with a few dramatic elements.

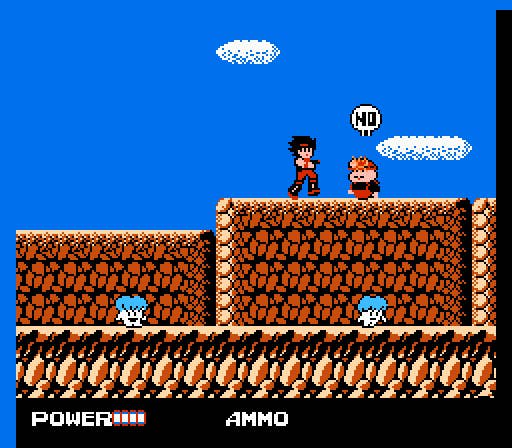

The wackiness frequently bled beyond the borders of the cutscenes and dialogue sequences (helpfully labelled as "TALKING TIME") and into the actual game mechanics. Shoot an ally character and they'd complain by way of a word balloon emblazoned with the word NO; return to where Bang's comrade was betrayed and murdered and the poor fellow's corpse would become progressively more decomposed (but cartoonishly so) with each visit. The plot's increasingly loopy twists and double-crosses went down more easily thanks to the fever delirium with which they were presented, and the loose, imperfect platforming shooting became a little easier to forgive because of the gung-ho style of the art and narrative.

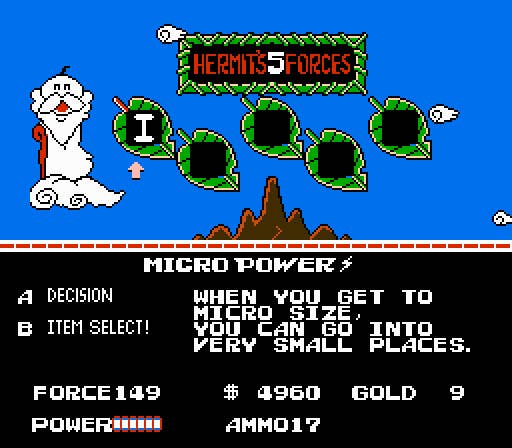

In a lot of ways, Clash was fairly ambitious for a platformer of its vintage. Its world sprawled across an expansive map of dozens of discrete stages linked by various routes, with Bang frequently forced to return to previously explored routes as dictated by the narrative or even to enter stages from a different direction in order to reach otherwise unaccessible areas. Bang could purchase weapons and tools to aid his exploration (the shopkeeper tended store with his tiny daughter by his side, a decidedly Toriyama-esque convention), and the boss encounters were each unique and inventive. It was a flawed game, no doubt, but an entertaining one.

Much of Clash at Demonhead's appeal came from its decidedly over-the-top manga influences, which gave the game a vital energy lacking in more serious NES contemporaries like Code Name: Viper or Top Secret Episode: Golgo 13 (which actually was based on a manga, but a far more straight-laced one). Thankfully, the snarling chrome-clad hero from the box had nothing to do with the reality of the game, which cheerfully paid homage to a school of slightly goofy Japanese cartoons that already was fading into obscurity.

American kids may not have understood the pastiche elements of Clash, but those who played it definitely responded to its hilarity (including Scott Pilgrim creator Bryan Lee O'Malley, whose work exhibits the same energetic, manga-influenced vibe as the game). Even more than today, publishers fretted back then about their packaging seeming too foreign, but they needn't have worried; slapstick insanity speaks its own universal language, and Clash at Demonhead's decidedly foreign personality turned it into a cult classic among players who didn't quite know what they were experiencing but who dug it anyway. The game certainly didn't single-handedly change American attitudes about foreign media, but it should be remembered as one more straw added to that particular camel's back.