Daily Classic: How Chrono Cross Triumphed Over Destiny

As a sequel to upbeat Chrono Trigger, this gloomy RPG should have been a wreck... yet somehow, it wasn't.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

As the sequel to Chrono Trigger, Squaresoft's Chrono Cross should have been a guaranteed hit, right? Wrong; by all rights, it should have a total disaster. That it was any good at all, in fact, should go down in the books as something of a minor miracle.

Chrono Cross' very existence posed several challenges. For one thing, the staff behind its creation only represented a fragment of the original talent behind 1995's Trigger; the key staff behind the previous game had largely moved on by 1999. At the end of the Super NES era, Trigger stood out because it represented a collaboration between two RPG "rivals," Dragon Quest and Final Fantasy: The former's creator, Yuji Horii, teamed up with the guiding force behind the former, Hironobu Sakaguchi, to build an RPG that combined the best of both franchises into something unique.

They did so with aplomb. Chrono Trigger possessed the simplified accessibility and relatable character writing that continues to define Dragon Quest, but it married these elements to the scale, pomp, and experimental design that had become Final Fantasy's stock in trade. Two schools of RPG discipline united in a singular work that sent players hurtling through millions of years of history to save the human race while at the same time feeling personable and fun. Trigger's systems offered flexibility but never became bogged down by fussy complexity, and despite spinning a massive tale about time travel and paradoxes, the plot deftly avoided needless convolution, presenting the most accessible, people-pleasing take on time paradoxes since Back to the Future.

But Horii and Sakaguchi had nothing to do with Chrono Cross. Instead, the sequel was left in the hands of Masato Kato, who had previously served as the sequel's lead writer and director. While Kato was certainly no hack – this was, after all, the man who planned and wrote Trigger's scenario and script – his post-Trigger work betrayed an inclination for considerably more baroque plot twists than Trigger had featured. His work on both Final Fantasy VII and Xenogears demonstrated far more elaborate (one might say "inscrutable") stories than anything in Square's 16-bit oeuvre, and it was this intricate approach to narrative, not Trigger's, that Kato carried through into Chrono Cross.

It's hardly fair to lay the abandonment of accessibility entirely at Kato's feet, however. Even more crucially than its change in creative leads, Cross also had to contend with a cultural change in RPG design and at Square in particular. The runaway success of Final Fantasy VII – which not only stood as the most successful game to date at Square, but one of the highest-selling releases on PlayStation, period – meant that publishers insisted that nearly every RPG to come down the PlayStation pipeline had to be huge and epic. "More, more, more" became the guiding philosophy: More arcane mechanics, more characters to recruit, more elaborate plot twists. The power and capacity of PlayStation relative to the cramped consoles that had come before sparked a veritable orgy of self-indulgence in RPG design.

Chrono Cross didn't simply reflect this trend; it embodied it. Here we had a game whose skill system made Final Fantasy VIII's Junctions look childishly simplistic, granting each character a handful of unique skills but otherwise making them entirely customizable. Each character possessed a huge grid of empty skill slots into which practically any ability in the game could be assigned, and the level (that is, location on the grid) of a given slot determined the relative power of the skill slotted into it. Combat operated on an incremental system in which players could spend a character's stamina on actions of varying levels of power, potentially even going into negative stamina in order to trade a turn for the change to execute an immediate high-powered combo – a system not unlike Bravely Default's, but much more elaborate. Add to that a feature in which the elemental designation of combat actions in turn determined the elemental nature of the battlefield, complex rules for activating summons, individual elemental affinities per character, secret combination attacks drawn from Chrono Trigger, and many other nuances, and you ended up with a system far more complicated than Trigger's low-friction design which simply gave each protagonist a handful of skills and a variety of ways to use them together.

Rather than adopting Trigger's reductive approach to party-building, Cross went the opposite direction. Players could team up not with six allies but with more than 40. Few were well-defined, however, and many were locked away behind obscure requirements and side quests. Cross' expansive party options felt like an attempt to mimic Suikoden or Pokémon, but minus all the characterization and character-specific traits that make those games' rosters so compelling. In the end, Cross offered about the same number of worthwhile characters as Trigger, but those few were practically lost amidst an army of chaff.

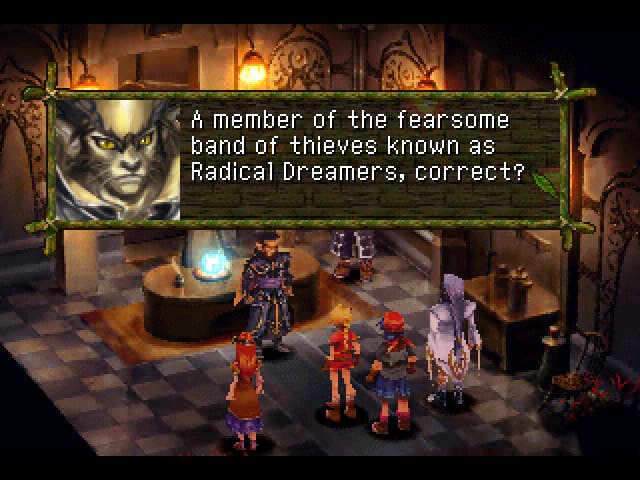

And then there was the story, which took Trigger's plot and explored every possible horrible outcome that could have resulted from its lighthearted time-travel romp. Rather than spanning millennia of time, Cross took place across two different realities (that is, branched timelines), and the "proper" reality turned out to be the one where the game's protagonist had died in childhood. Meanwhile, just about every character from Trigger turned out to have been murdered – including Robo, whose virtual personality is deleted right before the player's eyes – while a small and innocuous village on Trigger's mainland formed a massive army to crush the kingdom of Guardia, oh and by the way the planet itself hates mankind and will go to any length to make sure all humans are exterminated one way or another. Going from Chrono Trigger's happy-go-lucky save-the-world plot to Cross' we're-all-screwed grimness is like following up a Super Friends marathon with Man of Steel.

Taken as a sequel to Chrono Trigger, Chrono Cross is actually kind of horrible. It's not that Cross missed the appeal of Trigger so much as it isolated that appeal and then systematically set about destroying it. It seemingly went out of its way to undermine everything people enjoyed about the previous game. But that was kind of the point of the story: Crono and his friends from Trigger meddled in history with unforeseen consequences, and it was ultimately down to a boy who wasn't even supposed to be alive to set things right. In the end, Cross' story amounted to little more than resolving Trigger's biggest plot hole: What happened to Princess Schala after her self-sacrifice in the Ocean Palace? By resolving that mystery, players ultimately would heal time and set things right, and by all accounts the horribleness that spans Cross' tortuous plot would never have happened at all.

So if it plays nothing like Trigger and ultimately its entire story is wiped from reality, what's the point? Sure, if you say it like that, Chrono Cross sounds awful. But in truth, it's an excellent game. Bleak and dissonant when taken as a Chrono Trigger sequel, yes, but it's probably the purest example of PlayStation-era RPG design you'll ever find. Its elaborate systems seem like the very definition of "over-engineered," but they work together in unison to keep the game a constant challenge; the toughest battles work almost as puzzles, each with many possible solutions. The characters are the definition of slight – most of them have little personality outside of a hokey accent – but the core cast has purpose, while everyone else is there in case you want to have a giant voodoo doll, mushroom man, or baby alien in your party for some reason.

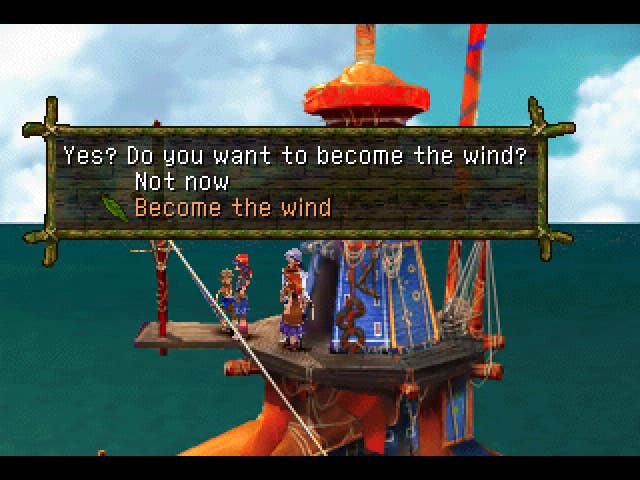

Most of all, though, Chrono Cross is a game about predestination. You can experience a shocking amount of trivial variety in each playthrough of the game, ranging from three different ways to approach the first major quest, to potential party members being devoured by monsters if you choose the wrong path. Yet the story always turns out the same. You can go to preposterous lengths to avoid allowing female lead character Kid into your party, but in the end the story ultimately revolves around her; despite your best efforts, you'll inevitably be drawn into her plot, although the game allows you to put it off for an impressive amount of time, accounting for a ludicrous number of minor story variants where Kid is involved. In other words, it basically amounted to a BioShock plot that was much more subtle about its message.

Chrono Cross may be a bleak and unsatisfying sequel for many Trigger fans, but it wholly embraces the strange, experimental, low-budget side of Square's PlayStation golden era. While clearly a far more modest production than your standard Final Fantasy – look at all the content recycling, including all times the pre-rendered cutscenes are reused! – that same B-tier status allowed the team to do their own thing. Whether it was appropriate to go off into the weeds of arcane game design in the form of a sequel to one of the most beloved RPGs of all time is certainly a matter for passionate debate. Take it on its own merits, though, and you may find Chrono Cross has the same anything-goes weirdness about it that makes Final Fantasy X-2 and Lightning Returns so interesting. In other words, your mileage may vary, but those who cotton to its peculiarities will probably love it.

.jpg?width=291&height=164&fit=crop&quality=80&format=jpg&auto=webp)