Daily Classic: An NES Hit Honed to Excellence in Castlevania III

The original Castlevania trilogy ended on a nearly perfect note.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

Castlevania III: Dracula's Curse was not quite a perfect game. Like so many works of mere mortals, it suffered from a few tiny flaws that held it back from those vaunted heights.

It came close, though, and the few shortcomings present in Dracula's Curse only seemed egregious by comparison to the utter brilliance of everything else about the game. It was a visual tour-de-force; its soundtrack raised the standard for game compositions, even in its gimped American format; its sheer size and variety, combined with the freedom to adventure in tandem with a second character, made it a game that begged to be replayed; and its level design made excellent use of its protagonists' varied-yet-limited capabilities to present devious challenges and optimal techniques for the clever.

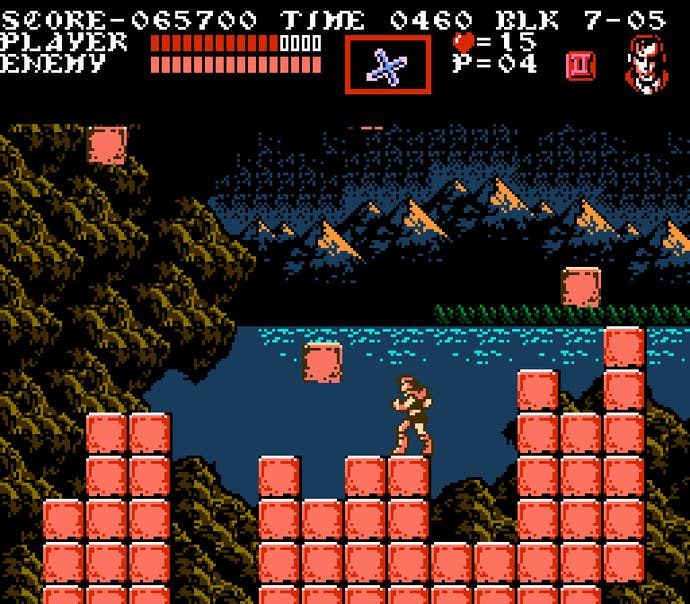

Really, Castlevania III's one false step came in a late and somewhat obscure stage, Block 7-05, a lengthy and grueling level whose second half included a protracted sequence in which bricks fell from the sky to create a path from the bottom to the top of the screen. The brick weren't random in their pattern, but they required careful memorization and left little room for failure. It was a weirdly unforgiving and arbitrary moment in a game that seemingly prided itself on thoughtful design.

But even then, that stage didn't ruin the game. The great thing about Block 7-05 was that it was totally optional; in fact, of the various routes through the game, it may well have been the hardest to come by. And even if you did chose that path to Dracula's castle, the companion who waited along that road and offered to team up with you -- the villain's own son, Alucard -- allowed you to practically cheat your way past the gauntlet of falling blocks.

One thing made this misstep remarkable: It was the sole serious design flaw in a huge and complex game. Unlike the original Castlevania, brief and sometimes maddeningly unfair, or the sequel Simon's Quest, vast, toothless, and opaque, Dracula's Curse managed to cram a tremendous amount of content into a single cartridge while walking a tenuous line between challenging and just plain hard. Players had to earn their victories, but the exceptional play balancing ensured losses were met with a vow of, "Next time I'll get it!" rather than, "Ugh, what crap."

Castlevania's creators had tremendous ambitions for the series right from the start. The NES original took the form of a compact and straightforward action game, but Japanese MSX owners received an alternate take on Castlevania just a short time later, one that reworked the NES game's stages into a series of self-contained free-roaming adventures. Simon's Quest extended that adventuresome sensibility well beyond Dracula's castle to incorporate the entire land of Transylvania. Dracula's Curse combined all of these concepts into a single spectacular whole.

While it played most like the original Castlevania, emphasizing precise platforming and simplified power-up mechanics (no shops or upgrades, just a pair of power-ups for the whip and a single interchangeable subweapon), Dracula's Curse took its cues for scale from Simon's Quest. The eponymous castle itself was slightly smaller than the one in the original Castlevania, but most of the adventure concerned Trevor Belmont's quest to reach his enemy's stronghold. Rather than roaming aimlessly across the countryside, though, Trevor could pick from several different paths and track his progress on a handy area map between stages. The design of each level matched up logically to the map reveal; going through the lowlands would see him tromping through marshes and caverns, while the overwater route took him via rotting galleon to a series of bridges and aqueducts. Sometimes, the route would change; taking the most direct route to the castle across the main bridge would cause the Clock Tower at the shore's edge to collapse, taking the bridge with it and sending Trevor along a more treacherous path.

Besides convincingly depicting the nature of the ground Trevor covered in the course of his adventure, the stage layouts also posed a challenge that perfectly complemented his skills. As with Simon in the original Castlevania, Trevor represented a fairly stiff breed of hero, measured in his pace and limited in his ability to jump. He could duck, whip in either direction, and wield one of several secondary weapons. But -- Block 7-05 excepted -- the entire game world reflected his limits. Jumps never exceeded his ability to reach the opposite side (except to hide a few bonuses accessible only by specific companion characters); enemies were always placed in a way that required quick reflexes and an understanding of Trevor's limitations yet always seemed fair to the observant player. The subweapons that appeared in a given area inevitably offered a specific strategic value for the rooms immediately following -- though tenacious players could often find advantages in hanging onto older tools as well.

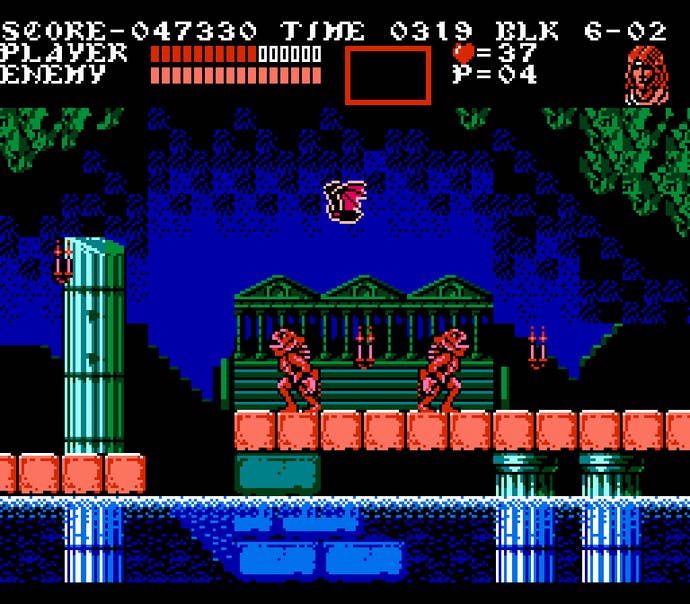

And then there were the companions. Along his journey, Trevor would encounter different warriors (which warrior varied based on his route) and could recruit them to his cause. Of course, players could also choose to go it alone and earn the game's most difficult ending, but taking a companion along offered tremendous tactical advantages. Each of Trevor's three allies possessed unique strengths, along with weaknesses to balance them out. Grant and Sypha were more fragile than Trevor, but the former's acrobatic prowess allowed him to dodge foes and scale walls or ceilings to quickly bypass difficult spots, while the latter wielded powerful magic -- the game's most devastating attacks. Alucard, on the other hand, could take a hit just as well as Trevor, but his fireball attacks were weak. Then again, he could also fly. Players could swap out Trevor for his current companion with the press of a button, instantly changing their combat capabilities to match the situation at hand. They shared Trevor's life bar, so it became essential for players to develop an instinct for which hero should be in use at any given time.

And all along the way, Castlevania III churned out unprecedented sights and sounds. Konami developed a special coprocessor for the game to enhance its graphical and audio capabilities, but even running on a stock Nintendo chip in the U.S. (where third parties either weren't allowed to use their custom chips or simply found it too prohibitively expensive to do so) the game looked amazing. It pushed the aging NES hardware to its limits, with the look and feel of entire stages often changing from section to section. One minute you're forging through the swirling mist of a nocturnal forest, the next you've climbed above the shroud to see the moon in a clear sky. While there was some repetition to be found, with the caverns of Alucard's route in particular feeling somewhat monotonous, the game designers wisely obscured these space-saving tricks by spreading them across different paths of the game (which were mutually exclusive) to prevent players from seeing the same content repeatedly in a single run-through.

Following Dracula's Curse, the Castlevania series abandoned the consistency it possessed during the NES days. The franchise became as mutable as Dracula's castle, retaining certain consistent elements while exploring different expressions of gameplay. Even Rondo of Blood -- of all the post-NES adventures, the one that most resembled Dracula's Curse -- led directly into a massive non-linear action RPG. Regardless of what you think of the series' 16-bit outings and beyond, Dracula's Curse is undeniably the perfect expression of its 8-bit concepts. Bigger, bolder, and more beautiful than anything that had come before, Castlevania III paired its technical craft with inspired (not to mention disciplined) game design. A true 8-bit masterpiece.