A Life Less Ordinary: Living a Virtual Life

"Life sims" are an interesting spinoff of the strategy and RPG genres, and with the current popularity of Animal Crossing: New Leaf, they're at the forefront of the public's attention at present. Pete investigates some of the most intriguing examples over the years.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

Video games tend to be regarded as an escapist form of entertainment, allowing us to switch off from the annoyances of everyday life and immerse ourselves in fantastic other cultures. So why, then, would you ever want to play a game that simulates the mundanity of a "normal" existence, whatever that is?

That's because "mundane" doesn't necessarily have to mean "boring," of course. And the types of games collectively known as "life sims" prove this fairly aptly, as anyone who has been playing Animal Crossing recently will attest.

Although the term "life sim" is used as an umbrella description, it's actually a fairly misleading one, as there are a diverse array of different interactive experiences that fall into that category -- some of which are more well-known than others.

"Life sims" tend to be one of two different types: freeform sandbox simulators, and stat-centric life sims with a degree of "direction" about them, though there's a degree of overlap in many cases. Let's have a look at both categories, including some prominent (and not-so-prominent) examples of both.

Activision's Little Computer People: The First Sandbox?

Most people credit Will Wright's The Sims as the originator of the sandbox life sim genre, but in fact it's much older than that. Specifically, in terms of mainstream releases that fit this description, the genre dates back to the mid-1980s and Activision's Little Computer People, originally released for Commodore 64, Atari ST, Commodore Amiga, ZX Spectrum and Apple II.

In Little Computer People (also known as House-on-a-Disk), each copy of the game generated a unique (but always male) virtual character who moved into the game's on-screen house. Said character would go about his daily business as the player watched, and the player was able to interact with them by issuing simple commands and even playing poker with them. Over time, the character would begin to initiate contact with the player on their own, inviting them to play games and even writing letters explaining their thoughts and needs. It was a largely directionless experience, but that didn't stop it being immensely compelling for a few hours at least -- and intriguing enough for Will Wright to cite it as an important influence in the development of The Sims.

Little Computer People was later followed by a Square-published spiritual successor in Japan known as Apple Town Story, which replaced the male character from Activision's original with a little girl and her cat. It was otherwise a fairly similar experience, albeit all in Japanese.

Little Computer People was well ahead of its time, and technological limitations held it back somewhat. Some 15 years later, however, The Sims attempted to realize some of the potential Activision's game had originally offered.

The Sims Hits the Scene

The Sims first came out in February of the year 2000 to a PC gaming community that was already well familiar with Will Wright's various forays into the simulation market, the most well-known of which was SimCity. Wright's previous work with Maxis had always been on a "macro" scale, however -- you were dealing with large-scale complex systems such as ant colonies, farms, cities and even entire planets. The Sims would be the first game in the sort-of-series that concentrated on a more "micro" level -- rather than looking at how diverse influences affected the system as a whole, The Sims would look at how outside influences affected an individual element of the system, and how those individual elements affected one another.

The first version of The Sims seems rather rudimentary by today's standards, though it still boasted a considerable amount more depth than Little Computer People ever did. Players could take on control of one or more male or female, child or adult characters placed inside either a custom-built or prefabricated virtual house and then direct their fate. The Sims' moods were determined by a combination of statistics that tracked everything from how much fun they were having to how much they needed to go to the toilet, and a simple level-up system allowed the little people to learn skills and become better at various aspects of their lives. Money was earned primarily by sending them out to work each day, and getting promoted was largely determined by the characters' skill levels.

Wright's previous work had always been on a "macro" scale; The Sims would be his first to concentrate on a more "micro" level.

Like many of Wright's other games, The Sims never ended; characters didn't age, though they could die if they starved, got caught in a fire, got electrocuted or drowned in a swimming pool. You generally had to make a significant effort to kill off a Sim, however, which led to the rather widespread practice of people experimenting with increasingly-devious ways to torture and kill off their little people. This was a perfectly valid way to play, however; throughout its entire history, The Sims has never punished players for experimenting and playing the way they want to. Indeed, in more recent incarnations, you can play a thoroughly evil character that attains considerable gratification from the misery of others; it's quite refreshing to have this much freedom in many respects.

Each new iteration of The Sims added a considerable amount of depth to the franchise; The Sims 2 added an ageing mechanic along with a genetics system that allowed characters to pass on various traits to their offspring, while The Sims 3 featured a coherent open world rather than isolated individual residences, along with the new "moodlet" mechanic, whereby a character's mood was more affected by specific things rather than the values of their "needs" meters. Over time, the series started to have a degree more "direction" to its gameplay -- The Sims 3 in particular has plenty of "objectives" to complete, particularly with the updates it has received over time -- but remains a largely open-ended experience.

Another noteworthy thing about the Sims series is that each entry in the series has also played host to a considerable number of expansion packs and, a few missteps early in the first game's lifespan aside, each of these also added a bunch of new gameplay mechanics to the base game. The Hot Date expansion for the original game, for example, added considerably more depth to interpersonal interactions, while the University expansion for The Sims 2 added a whole new life stage where Sims could, unsurprisingly, go to University.

It's The Sims 3's expansions that have provided the biggest shake-ups to the formula, though: World Adventures adds dungeon-crawling, puzzle-solving and treasure-hunting; Ambitions adds the oft-requested ability for players to take control of their Sims while they're at work as well as at home; Late Night transplants the series' trademark suburban gameplay into a more urban environment with more opportunities to meet virtual people.

The Sims series is a benchmark for sandbox life sims, and remains arguably the best of its type out there. That hasn't stopped various developers from trying to imitate it over the years, of course -- perhaps most notoriously, Deep Silver released a game called Singles: Flirt Up Your Life in 2004, which was effectively an insultingly easy, sexually-explicit version of The Sims 2. Suffice to say, it wasn't particularly good, and Maxis' iconic series hasn't really ever been matched.

Crossing the Animal Tracks

About a year after The Sims hit the market in the West, Nintendo released Animal Crossing to an unsuspecting Japanese public. Originally an N64 game, Animal Crossing was quickly ported to GameCube in the space of eight months for international release, and to incorporate numerous features which had had to be stripped from the N64 original.

Animal Crossing, lest you've somehow missed everyone talking about the latest installment recently, is an open-ended sandbox game, but it goes about simulating life in a very different manner to The Sims. Rather than allowing the player overall strategic control of a whole family and tasking them with seeing to their needs and ambitions, in Animal Crossing, you take control of a single avatar that is your presence in the virtual world. You're the only human character in an environment otherwise entirely populated by anthropomorphic animals, and the reason why you are where you are is never really explained.

There are no real "responsibilities" to go along with your character's "rights" in Animal Crossing.

In contrast to The Sims, there are no real "responsibilities" to go along with your character's "rights" -- you don't have to manage their health, hunger, bladder status or anything like that. Instead, your avatar simply acts as your projection into the world, and your means through which you can interact with the characters. It's entirely up to you how you play the game -- many players gravitate towards making their house as big as possible as the main "goal" of the game, but there are a wide variety of other things to do: collecting items, fishing, digging up fossils.

Crucially, as this is a key aspect of most life sims, there's still a sense of progression, though. Your house fills with cool stuff and expands; the village sees new residents arriving and old ones leaving; the "main street" of your village gradually grows and changes with new shops and expanded versions of existing ones.

In an interesting contrast to The Sims, which made use of an accelerated timescale to allow many days to pass in a single play session, Animal Crossing unfolds in real time, meaning that in order to see certain characters or participate in certain events, you have to play the game at specific times or on specific days. This is something which has been maintained in subsequent entries in the series, and is one of the things that keeps the game interesting over time. Particularly early in the game, new things happen almost every day -- new characters are introduced, new play mechanics appear, new places to explore are revealed.

Animal Crossing also distinguishes itself from The Sims in that it's an inherently social game -- in order to get the most out of the game, you need to play with others. This is something that has been made significantly easier in the most recent 3DS iteration of the game thanks to the magic of wireless connectivity; in the GameCube original, you had to make use of a friend's memory card to "travel" to their town, while in the 3DS version, you can visit and play alongside them using either local wireless or Internet connectivity.

Animal Crossing is perhaps slightly harder to get into than The Sims due to the fact what you're "supposed" to be doing isn't so clear-cut -- while free-form, The Sims at least has recognizable mechanics such as bars you need to keep filled and skills you need to improve, while Animal Crossing basically just drops you into a strange new world and tells you to get on with it. Both approaches are valid, but both will doubtless appeal to different types of people.

Building a Better Princess

While open-ended, freeform sandbox life sims were developing from Little Computer People to The Sims, Animal Crossing and beyond, a completely separate branch of the "life sim" genre was forming, and is still going strong today, albeit in a somewhat less-visible format in the West.

Princess Maker hit Japan in 1991, and provided an interesting spin on the stat-based role-playing game genre. Rather than taking control of a legendary hero on his way to defeat some great evil, players instead took on the role of a foster parent caring for a war orphan named Maria. It was the player's responsibility to see to her upbringing from the age of 10 to 18, building up her skills and nudging her in the direction of a particular job in the process. Each game in the series has a ludicrously huge number of endings according to whatever job your "daughter" ended up doing (including some "dark side" jobs such as prostitution or crime lord), whether or not she was successful at it, and whether or not she managed to find a husband and/or start a family in the process.

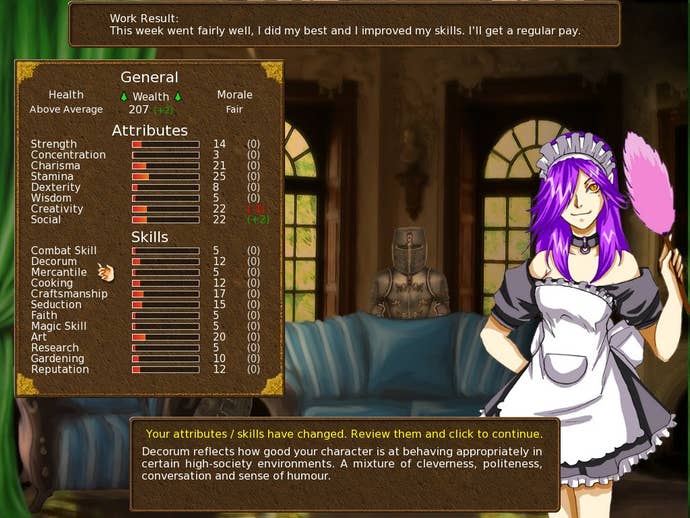

Princess Maker's gameplay largely consists of managing your foster daughter's free time in such a manner that will build up her statistics and skills. Various iterations of the series over the years have also added a variety of different mechanics, ranging from top-down RPG-style adventuring to visual novel-style "events" in which the player must determine the best way in which the young wannabe princess should act.

The Princess Maker series was enormously influential on the modern stat-centric life sim genre. While we don't tend to see too many The Sims imitators these days -- it seems that Singles: Flirt Up Your Life's poor critical reception may have played a role there -- we do see a lot of Princess Maker-style games. Interestingly enough, these often tend to come not from Japan, but from independent Western developers seeking to imitate or pay homage to the typically Japanese-style gameplay.

Pretenders to the Throne

Winter Wolves Games' Spirited Heart is one of the most obviously inspired by Princess Maker, casting players in the role of a human, elf or demoness girl coming to a typical fantasy-realm city for the first time. By taking on various jobs, success in which is determined by a dice-based gambling minigame, the player can build up their character's skills, earn money and attempt to build a better life for them.

There are several ways to "win" Spirited Heart: get your character married off to one of the (male or female) potential suitors throughout the game; survive for 10 in-game years; or complete a special task given to you by your race's goddess. It's an interesting game, for sure -- perhaps not the best, particularly in terms of writing for some of the romance sequences, but certainly a good example of the Princess Maker mold, and well worth a play or two. (It's also noteworthy for being friendly to both homosexual and bisexual characters -- you can buy the game in either its heterosexual edition or the same-sex romance "girl's love" version, or combine the two together to keep your virtual romance options open.)

Magical Diary is particularly noteworthy for its strong use of allegory, but its "life sim" mechanics are also used particularly well.

Independent developer Hanako Games, aka Georgina Bensley, is also rather fond of Princess Maker-style mechanics, and frequently incorporates them into her games. Bensley's titles also tend to have a visual novel-style storyline flowing through them as well as the emergent narrative that comes from building up your character's stats.

Magical Diary is one of Bensley's more interesting titles, casting players in the role of a young female student gifted with the power of magic and heading off to a Hogwarts-style magic school for the first time. Through carefully scheduling your time, learning magical spells and interacting with your fellow students, you'll have to do your best to steer your character right and make sure she doesn't fall victim to the many perils the magical world has to offer.

Magical Diary is particularly noteworthy for its strong use of allegory to represent surprisingly mature concepts such as abusive relationships and rape, but aside from those facts, the "life sim" mechanics are used particularly well for solving puzzles and offering interesting new solutions to various situations. The most obvious use of these comes in the school's regular "exams," where your character is thrown into a dungeon and tasked with finding her way out using the spells she has learned. Different spells provide very different potential solutions!

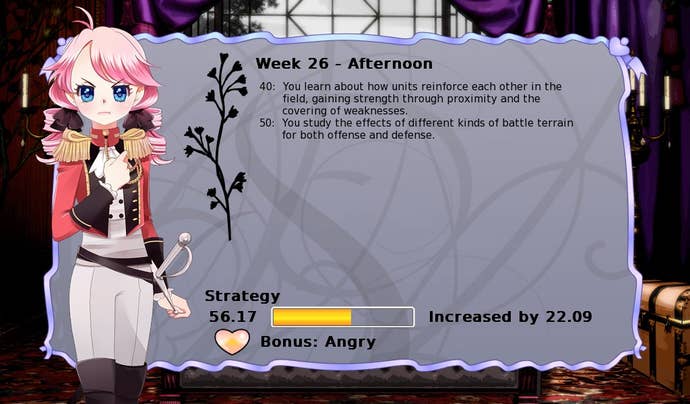

Also from Bensley, Long Live the Queen is perhaps closer to the original Princess Maker mold in that you literally take on the role of a young princess as she endures various hardships. The land of Long Live the Queen is a brutal one, however, and there's absolutely no guarantee that our heroine will make it through the entire story alive; indeed, the game's main menu includes a "checklist" of all the possible ways that you can die over the course of the story.

The game spins an interesting tale that changes significantly according to the choices you make regarding the young royal's upbringing, and is a good example of how stat-heavy gameplay can be well-integrated with well-written storytelling.

For a rather more low-key twist on the Princess Maker style of gameplay, the Japanese-developed Cherry Tree High Comedy Club, brought to the West by Nyu Media, is a great example of how stat-centric life sim mechanics can be used in a real-world context as well as a fantasy realm. Casting players in the role of a teenage girl who has about a month to recruit a selection of misfits into her comedy club, this rather charming little game is entertaining and amusing, and is a great game to point to if you're looking for examples of well-produced non-violent games.

It's also a game which often draws comparisons to a certain series by Atlus, which brings us nicely on to our next topic.

Work-Life Balance

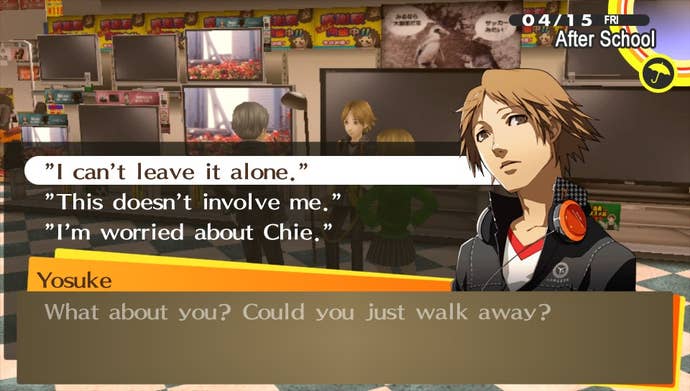

Perhaps the most well-known example of a relatively "mainstream" game adopting life sim-style mechanics is Atlus Persona series. While these games started out as relatively straightforward JRPGs with an interesting modern-day setting and premise, with Persona 3, the series took on the distinctive structure it has today: roughly 50 percent life sim, 50 percent dungeon-crawling RPG.

On the off-chance you've never played Persona 3 or 4, allow me to explain. In both games, you play the role of a new transfer student who comes to a Japanese school and makes some new friends who all have something in common: the ability to summon a Persona, a being that lives inside you and helps you overcome life's hardships. The protagonist's Persona-summoning ability is special, however: while his compatriots can only summon a single Persona, he is able to summon many different ones.

The exact Personas he can summon are determined through his "social links" with people in the real world, and thus playing Persona 3 or 4 becomes a matter of managing your time effectively so you can build up your various social stats, hang out with your friends and then make use of these social links to power up your Personas for use in the dungeon-crawling aspect of the game. Each social link has its own mini-story to follow, and discovering the deepest, darkest secrets of all the incidental characters is one of the most addictive, interesting parts about Persona 3 and 4.

Why Live a Virtual Life?

The reasons players have for playing and enjoying life sims are many, but a big part of this genre's appeal can probably be attributed to the fact that they tap into the reward centers of the brain through a constant sense of progression.

It's pretty rare that you'll find yourself stagnating in a life sim, regardless of whether it's a sandbox-type game or a stat-centric title: in Animal Crossing, you'll find something new to collect, or a new character will appear; in Princess Maker-style games, you're always improving at least one of your stats; in Persona, the story moves onwards with each passing in-game day regardless of whether you're "ready" for it or not. And we haven't even touched on the nature of living a virtual life in an online space -- but that's probably a topic for another day.

And, of course, as we said at the beginning of this piece, games are an escapist form of entertainment. Just because some games focus on more mundane things than others doesn't make them any less escapist; living someone else's rather ordinary life for a little while is just as valid a fantasy as pretending to be a powerful dude with a big gun, or an improbably-bosomed lady with a physically-impossible sword, or... you get the idea.

Try living another life for a little while. You might be surprised how much you enjoy it.