A-B-C-DW: Do Video Games Really Rot Your Brain?

Not so, says someone who learned to read through games like Dragon Warrior.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

Although the media is coming around to the idea that video games don't train kids to push old ladies into traffic and steal their Rascal scooters, the pastime hardly enjoys uncontested mainstream approval. Video games certainly aren't celebrated for their potential as learning tools, at least not outside of obvious fare that involve Muppets counting slowly.

In fact, the media often portrays games as education's most resilient enemy. According to reports, games gobble up time and attention that should be spent on reading and homework. While it's understandably hard to sell a kid on his or her math homework while he or she is bounding through the Mushroom Kingdom, parents who brand games as the antithesis of learning and shut them out altogether are doing themselves and their children a disservice. I know for a fact that video games can encourage children to nuzzle deeper into an inborn love for reading and writing. I know, because that's how it happened for me. Games also made it so I could learn vocabulary real good.

Your Enlightenment is in Another Castle

My earliest game systems were the ColecoVision and the Atari 2600, but Super Mario Bros. for the NES was the first title that really managed to sink its teeth into my young brain. Its barebones story was more like a thread that kept Mario moving from left to right, but even "the Princess is in another castle" can seem like Pulitzer-winning stuff if you're not used to games offering an incentive beyond, "Your father just destroyed your Missile Command score. Better do something about that, girl."

When I saw Super Mario Bros. for the first time at a birthday party, I wasn't necessarily impressed by its graphics or its gameplay so much as I was blown away by the realization that a video game could be an interactive storybook—something so much more interesting than the score counters on my Atari 2600. I gawped as my host's mother worked her way through the game while the party-goers around me adopted Barbie dolls as microphones and screamed pop songs into tangled nests of faux blonde hair. Thinking back, I guess isolating myself from the goings-on made me an awful party guest, but I was on the cusp of a life-changing event.

I assure you, I did rejoin my friends in time to eat cake.

Writing With Erdrick

It was a while before I was able to secure an NES of my own. Times were hard, and my parents were not made of money. They opened a vein in front of me to prove it (kidding -- sort of). I was about 11 years old when I received my NES, which, incidentally, was around the same time I started earnestly punching out stories on my school's chunky Macintosh Plus keyboards. I quickly discovered that my love for video games fed into my love for writing, and vice-versa.

I'd enjoyed penning my own stories since I was a little girl, and the books and comics I read at the time inspired the worlds that were born on my stacks of newsprint (my earliest works were based in the Archie universe—I'm sorry, Mr. Goldwater). But something about the interactive nature of video games threw open a channel in my head and let ideas pour out in a torrent.

I don't just mean fan fiction. I wrote plenty of that too, including a story wherein the brotherly love between Mario and Luigi dissolved and the two wound up fighting and swearing at one another, ultimately leaving the princess to rescue herself. No, many of my works were original stories inspired by the worlds, characters, and situations I met in the games I loved.

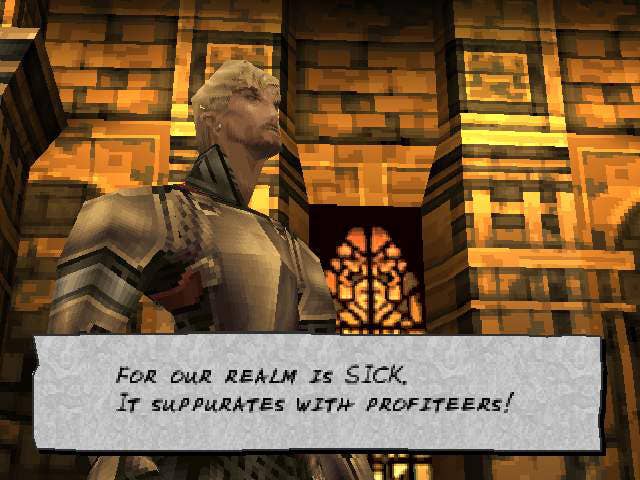

Dragon Warrior series made the biggest impression on my earliest attempts at serious, novel-length fantasy writing. Emphasis on "Warrior" over "Quest;" the faux-Shakespearean English used for the former's localization really fascinated me for some reason, and I adopted it (inaccuracies included) when I wrote my first story about dragon-slaying. In it, a young boy undertakes a mission to skewer a dragon, mostly because a king tells him to do so. Along the way, he inexplicably finds gold tucked in the corpses of his enemies, upgrades his equipment, and grows in the same manner as Erdrick's lonely descendent in the first Dragon Warrior title. The boy in my story does befriend a griffin, however, which gives him one up on Erdrick's bloodline. I even included an illustration of the boy and his beast, though drawing on an uneven surface made it look as if the left side of the boy's face had collapsed.

Parents constantly struggle to convince their kids to read, and for good reason. An early start on reading can help cement a love for learning. What some critics of video games fail to realize is that certain games can supplement the benefits that books provide. I was too young for Lord of the Rings when I wrote my first fantasy adventure, but the easy-to-follow story of Dragon Warrior combined with its appealing visuals to form a digestible experience that I eventually made my own.

Mythology, Culture, and Cross-Pollination

Video games can also teach kids about traditions and beliefs from other cultures, even if they don't realize they're being educated until years down the road. How many '90s kids knew what a tanooki (tanuki) actually was, aside from a "teddy bear suit" that helped Mario fly and turn into a statue? And how many kids today know the cultural significance behind the tanuki? Granted, at least today's children can hit up Google and get an immediate answer. Today's 20- and- 30-somethings have contented themselves with chuckling about how Nintendo must've been "sooooo high" when it decided that a leaf would grant Mario the power of flight.

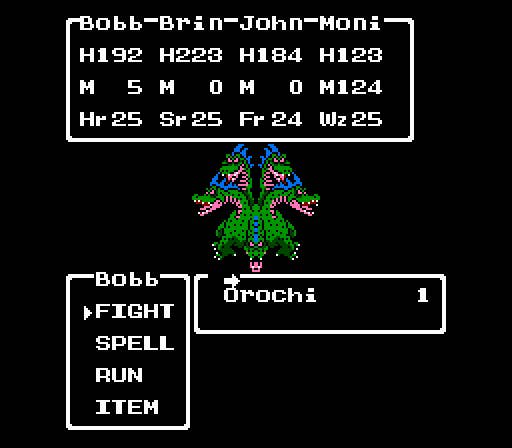

To be fair, even Japan tends to utilize its myths and legends outside of context for its creative works—not unlike how Greek mythology's Minotaur is a catch-all name for any bull-headed man, and is not explicitly the misbegotten result of the queen of Minos making it with a bull. So maybe I can be forgiven for adopting and misusing the Shinto religion's fearsome Orochi monster without having a clue about its true nature.

The year was 1992 or somewhere thereabouts, and I made another crack at a fantasy novel. I still have it; it's written on cheap newsprint, line after thick, clumsy line obviously made with a dull pencil. One corner is peppered with staples. Dragon Warrior III was to blame for this particular project. As Enix's world had grown, so had my imagination. My story goes from the "real world" to a parallel fantasy universe wherein the heroes (more than one this time—like in Dragon Warrior III) fought a variety of monsters and dragons, and even travelled to the underworld, the domain of (sigh) Orochi.

Though in retrospect, Japanese legend doesn't paint the eight-headed dragon in a flattering light, so the underworld would be a comfortable domain for the beast. Merely a happy coincidence, however. Orochi was portrayed as a multi-headed, maiden-eating dragon in Dragon Warrior III, and I assumed the game's writers had made him up for a single side quest.

Video games need not be all about the butchery of culture and religion, however. Once I realized the Orochi myth runs deep, I was inspired to learn more. Games are full of neat cues that can inspire players to research legends and symbolism.

Learning Can Be Fun. Honest.

When we talk about the positive side of video games, we bring up how games improve hand-eye coordination, or enhance our problem-solving skills, or simply help us wind down when we're stressed. Those are all great reasons to tuck into a video game, but games rarely get deserved credit for unlocking our creative energies. You might not get up from a game, sit down at your computer, and automatically pound out the next best-selling novel, but you might get a good start on one.