10 Years Ago, New Super Mario Bros. Made Old-School Cool… or Profitable, Anyway

The only thing truly "new" about Nintendo's DS blockbuster was the notion that maybe classic platformers still had a place in the world, but that was enough to make a difference.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

A decade ago this week, Nintendo debuted one of its most revolutionary creations ever: New Super Mario Bros. for DS. That game's revolutionary achievement? It proved games don’t have to be revolutionary in the sense of inventing new, groundbreaking concepts in order to make an impact.

In other words, NSMB made a difference by being, well, old. Many critics have lamented long and loud the irony of such a brazen throwback of a game wearing the title "New" Super Mario Bros. That seeming misappellation, however, sits at the very core of the game’s success: It went on to become the 10th best-selling retail game of all time, and the second best-selling Mario platformer to date (right behind the original Super Mario Bros., which enjoyed the benefit of being a pack-in title for most of the NES's life). To put it in perspective, NSMB was the top-selling game on the second most successful game console ever. By any definition of the word, it was a massive hit.

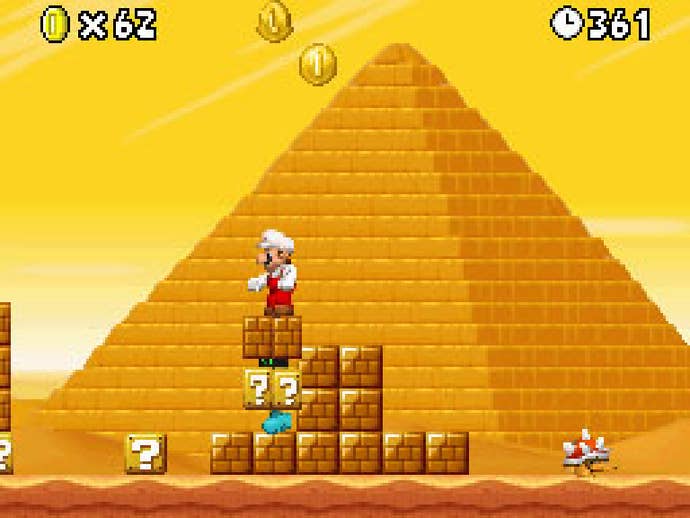

New Super Mario Bros. makes for an interesting study in contrasts versus the original Super Mario Bros. That 1985 classic set a new standard for video games, offering unprecedented depth, variety, and control mechanics — a tremendous achievement in action game design. More than 20 years later, its DS follow-up did almost exactly the opposite: It threw out the innovations and refinements of Super Mario's sequels through the years, abandoning the three-dimensional platform design of Super Mario 64, the complex level design of Super Mario World, and the breadth of power-ups seen in Super Mario Bros. 3. Despite its title, NSMB was the most basic and stripped-down Mario adventure since Super Mario Land for the original Game Boy.

While many long-time Mario fanatics found the game's lack of invention to be a disappointment, its predictability — its familiarity — proved to be its strength.

"I picked up [New Super Mario Bros.] right when it came out, and remember being really excited to play a 2D Mario again," says James Petruzzi, designer of the upcoming pixel platformer Chasm, which he acknowledges drew some influence from Mario's DS smash ("I was actually inspired by its great wall-jump mechanic for Chasm," he says). "I liked the 3D Mario games on Nintendo 64 and GameCube, but they just didn’t scratch the same itch for me. So in a way, it felt like a real follow-up to Super Mario World."

Petruzzi wasn't alone. On the contrary, Mario's backward-facing sequel appealed to millions of people precisely because it reminded them of games, and game design, from long ago. Nintendo couldn't have timed the game's release better: The DS had finally picked up genuine traction thanks to a strong roster of holiday 2005 releases, and the DS Lite hardware revision — which would outsell the standard DS model by a factor of five or six — had just debuted in Japan and was less than a month away in the America and Europe. The DS's roster of unconventional games like Nintendogs and Animal Crossing: Wild World had cemented the system's popularity with a much wider audience than the typical gaming crowd, and New Super Mario Bros. was a perfect follow-up. It offered familiar, rock-solid action that appealed to older players by stirring primal memories of the NES while snaring new fans with its accessibility and raw appeal.

"I loved it," says Dan Adelman, an indie gaming business development consultant who is currently working with Petruzzi on Chasm. "The color palette was bright and cheerful, the controls tight, and the level design was varied. After putting out so many Super Mario Bros. games over the years, Nintendo could have just churned out more levels with shiny new graphics, but they put in a lot of new touches that weren’t possible before. I think everyone remembers the first time they saw that giant Mario sprite. It made the whole level feel tiny by comparison. You could also become mini Mario, and there were a bunch of small physics effects that added a lot polish."

"I remember the first time I got the large mushroom powerup, and laughing with delight as I barreled through the terrain," agrees Petruzzi. "Both the shrinking and growing felt like a really good use of the 3D, something that would be incredibly hard to do with sprites. The wall jumping also felt fresh and very intuitive."

"I think what it did incredibly well was re-introducing gamers to classic Mario gameplay while updating the graphics to suit the modern age," says Active Gaming Media designer Nayan Ramachandran. NSMB effectively turned back the clock of the Mario series to the late ’80s; despite its mix of modern polygonal and pre-rendered graphics, its play mechanics, structure, and general aesthetic seemed to sit somewhere in between the first and third Super Mario games for NES. More complex than Super Mario Bros., but less elaborate than Mario 3, you could almost believe that NSMB was the real Super Mario Bros. 2.

NSMB made only a few modest additions to Mario canon. Mario gained a wall jump that worked much like that in the Mega Man X games; in addition to the standard Super Mushroom and Fire Flower power-ups, he could also gather the new Mega Mushroom — which allowed him to grow to tremendous size and smash through the scenery — and the Micro Mushroom, which allowed him to shrink, make floaty jumps, and run along the surface of water. There was also a rare Blue Shell that allowed Mario to spin almost uncontrollably through the scenery, a fun but risky skill. All of these new skills appeared infrequently and had extremely limited utility (the Mega Mushroom power-up appeared only a handful of times and wore off after about 15 seconds), placing the emphasis firmly on old-school power-ups for most of the game. It was, above all, a back-to-basics rendition of Mario. Even its level-progression world map offered only a handful of secrets and alternate routes, with a far more linear layout than that of Mario 3.

In short, Nintendo played it safe with NSMB, which disappointed many long-time fans. "I liked it a lot," says Axiom Verge designer Tom Happ, "but I think in retrospect this was more because of its resemblance to Super Mario World and Super Mario Bros. 3 than because of its own merits. I wish it had brought something more interesting to the table than just repeating the past, now with 2.5D effects. Remember how [SMB3's] raccoon tail significantly changed how you played the entire game? Couldn't they do something with the same degree of freshness as that?

"I think of this game as being a bit more like that Disney revival in the '90s where they just started aping the old formula without understanding that the old formula only worked because it was different from what came before."

"If I had to nitpick," muses Adelman, "I’d say that it would have been good to see even more innovation, but that might have defeated the purpose. It had been so long since people had a really good new 2D Super Mario Bros., they just wanted a well-polished experience. I think a lot of the innovation went into games like Super Mario Galaxy, which came out about a year later."

Polish over innovation may as well have been the mission statement behind NSMB; what it lacked in new ideas it made up for in sleek refinement. If anything, it may have been too refined; level designs lacked the go-for-broke wackiness of older Mario games, and the game's new enemy types turned out to be bland and unmemorable. On the other hand, it played smoothly. Unlike the overwhelming majority of 2.5D games of this style, NSMB presented tight controls and precise platforming, lacking the nebulous collision detection and general floatiness people had come to association with the format. Its quality was no coincidence: The core team behind NSMB had plenty of experience with the Mario series.

Producer Hiroyuki Kimura and director Shigeyuki Asuke had both been heavily involved in the Mario Advance series for Game Boy Advance, and the time they spent restoring those 8- and 16-bit classics for the 21st century gave them a unique inside perspective on the nuts-and-bolts of making Mario. After churning through the Advance line, NSBM offered them their first chance to put their experience rebuilding the classics to the test. In hindsight, NSMB definitely feels like a first ride without training wheels; the duo would go on to produce New Super Mario Bros. Wii and its Wii U sequel, along with Super Mario Maker, and each of these creations feels more ambitious and creative than the last. The duo clearly grew in confidence with each release.