With Metroid, Indies Do What Nintendon't

Even though the people behind the Metroid series seem content to let their beloved creation lie dormant, independent developers are picking up the slack.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

"Metroid clones." "Metroidvanias." "Castleroids." "Free-roaming exploration-based platformers requiring upgrading your equipment and skills in order to progress." Call 'em what you will, they're a long-time fan-favorite... and these days, you can't swing a dead cat in a room full of indie developers without hitting a few guys who are currently developing their own take on the genre.

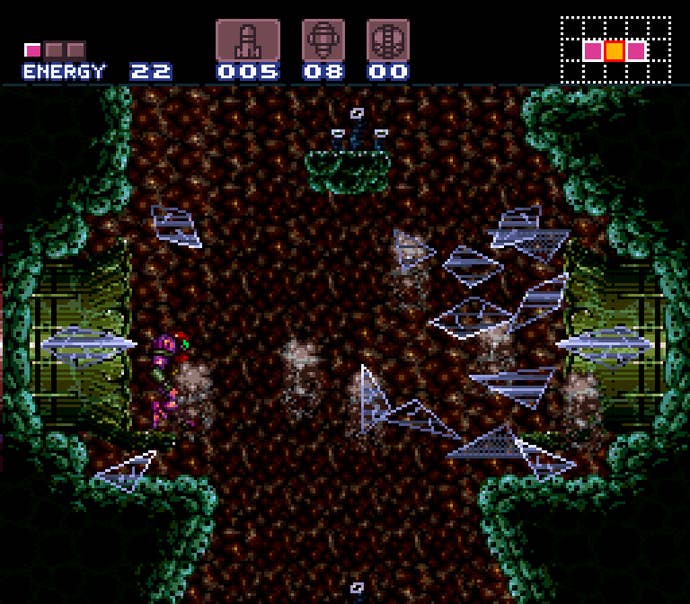

The origin of Metroid-style games lay, reasonably enough, with Nintendo's 1986 masterpiece Metroid. It's not quite so cut-and-dried as that, of course, and I've even made a small side project of chronicling the format's origins and evolution. But for all intents and purposes Metroid, represented a jumping-off point for the medium: The moment at which platform action games pushed beyond single-screen challenges of dexterity and linear obstacle courses to become something grander.

The structure of Metroid created a smooth, natural difficulty curve as a built-in function of the game's fundamental premise. Its design philosophy has gained considerable popularity over the past few years as action games have folded elements of RPGs and adventures into themselves, and even the likes of Rocksteady's Batman games -- ostensibly stealth-focused brawlers -- have borrowed "metroidvania" mechanics to enrich their design.

In fact, just about the only place you won't find Metroid-style games is in Nintendo's current library. The last proper and faithful Metroid sequel arrived more than a decade ago, with 2002's Metroid Fusion. Since then, the series has seen a great remake (Metroid: Zero Mission), some good-to-excellent first-person shooters that increasingly strayed from the series' original approach to structure and progression (Metroid Prime), and a total misfire that appears to have put the kibosh on the franchise for now (Metroid: Other M). The company's apparent disdain for its own legacy is downright baffling; while it cranks out multiple Mario and Zelda games each year, Metroid has been downgraded to mere reference fodder in games like Nintendo Land and Smash Bros.

Metroid fans certainly aren't out of luck, though. Nintendo's Metroid-shaped hole has been filled -- amply so -- by a huge array of independent developers. More games than ever are being produced in the Metroid vein; the difference now is that they're coming from small studios rather than the major publisher who established the format in the first place. Why has Nintendo abandoned one of its most beloved properties, and why have indies been so quick to pick up the slack?

"Everyone wants to make Metroid," says Kenny Lee, co-creator of the recent indie breakout Rogue Legacy. "The concept itself is just really solid. When you're brainstorming ideas, the first thing that jumps into many minds is, 'Let's make a Metroid game.'"

"It’s my favorite style of game," agrees Moise Breton, who recently Kickstarted his own Metroid-inspired project, A.N.N.E. "In Metroid, for example, you have very little text. The story is told mostly with the environments and real-time events. It’s easy for me to get immersed in these kind of games. Exploring is a real treat, and it’s really what keeps you playing -- you want to see more of the world. I don’t have that much time to play games nowadays, and when a game has a lot of text, I tend to mash buttons until it’s all gone so that I can play again."

Metroid's intricacy naturally appeals to the detail-oriented types who long to make video games themselves. And it's no coincidence that the uptick in Metroid clones comes in tandem with the growing ability of amateur developers to create their own complete games from start to finish, explains Tom Happ, who is currently hammering away at his own Metroid-like indie project, Axiom Verge.

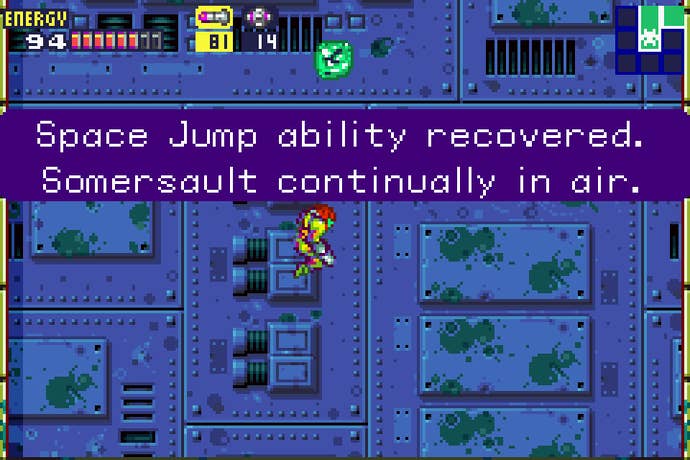

"Vast improvements in tools, funding, and distribution methods make it much easier for anyone with an interest to try making their own metroidvania," Happ observes. "I used to be involved in the GBA homebrew scene, and it had this kind of overtone that you were doing something underground and maybe a little bit naughty. Documentation was kept locked up, so people had to reverse-engineer the hardware just to learn how it worked, using peripherals that were more or less contraband. You knew that without an official Nintendo license your games were destined for obscurity, so it wasn't something you'd make a large investment in.

"Once the iPhone and its App Store came about, everyone started waking up to the viability of indie development, and the goal shifted from trying to keep everything exclusive, licensed, and official to being open. Dean Dodrill taught himself to code when he made Dust: An Elysian Tale entirely on his own, which in 1994 would probably have taken about a dozen developers, all well-versed in assembly -- not to mention a lot of esoteric in-house tools, development hardware, and the infrastructure to make and support them.

"So now we have a lack of true Metroids (or even Castlevania, really) and a bunch of people who love that style of game and don't need anyone's permission to make and sell it. I think it's kind of coming to its obvious conclusion."

"Metroid was, as far as I know, the first in-depth platformer exploration game," explains James Petruzzi, whose Chasm launched a successful Kickstarter this spring. "I think its influence on us comes in two parts: First, that the world is 'open' in the sense you’re not locked into a left-to-right level structure and have the freedom to backtrack; and second, that you obtain keys not only in a traditional key/lock format but also as improvements to your character.

"Beyond the mechanics, I think there’s also something to be said for Metroid’s dark atmosphere, lack of hand-holding, and overall difficulty. The world feels like a place that’s indifferent to your presence, not one that’s built to cater to it, and that makes all the difference."

Of course, the sense that Metroid's world isn't built to cater to the player is entirely illusory. Perhaps more than any other style of game, the metroidvania genre is elaborately constructed as a puzzle to be solved by the player alone, with gates to progress that can be conquered only by a weapon or other tool conveniently acquired in an area directly preceding it. This balancing act of level layouts and perceptual deception may be one of the most difficult tricks of presentation for a game designer to effectively duplicate; even Nintendo didn't get it quite right until the Super Metroid, the third entry in the series.

"It's difficult to name many games that do the Metroid style right," admits Lee. "There's like, Metroid and its sequels, and Shadow Complex. Those are the big, true, Metroid-styled games. But everyone thinks they can do it, so a lot of developers end up trying to tackle it with varying results.

"I say 'varying results' because making those mechanisms work is really hard to do. To make it work you need really strong gameplay ideas and even stronger level design. And for a lot of people, once they get into the nitty gritty they realize how much work is actually required."

And Lee is correct: The Metroid format is complex, and it's correspondingly difficult to do right. Few of the most popular indie games in that vein are absolute renditions of the full Metroid experience and instead borrow elements and ideas to integrate into a more linear design. Daisuke Amaya's seminal indie work Cave Story, for example, offers much less open exploration than it's often given credit for, with only a minimal amount of backtracking. It's an excellent game, but it's far less intricate than something like Super Metroid.

Ever since the 1986 original, the Metroid games have allowed players (as bounty hunter Samus Aran) to traverse a complex underground labyrinth of corridors and shafts in a mission to defeat the enemy boss Mother Brain. While that first entry in the series operated with the side-scrolling mechanics of contemporaries like Super Mario Bros., Ghosts 'N Goblins, and Wonder Boy, Metroid differed in the fact that you could -- indeed, had to -- backtrack. Your only goal was to defeat Mother Brain, but in order to do so you first had to defeat two bosses that held the keys to her lair. And reaching those bosses, in turn, required the acquisition of certain power-ups scattered throughout the maze.

Those power-ups involved more than just making Samus' weapons more powerful; each served as a key as well, in its own way. This was Metroid's real stroke of genius: Upgrades were both progressive and permanent, not fleeting bonuses that vanished within seconds. To reach the vital Varia Suit that halved enemy attacks, Samus first needed the High-Jump Boots; but in order to acquire the High-Jump Boots, she needed the Ice Beam to freeze enemies to serve as stepping stones; but she couldn't get those without Bombs to access the chamber housing the Ice Beam; in order to acquire Bombs, she needed Missiles to open the Bomb room; and before she could pick up Missiles, she needed the Maru-Mari ("morph ball") so she could pass through the narrow passages beyond the entrance to the labyrinth.

The resulting chain of acquisition felt more akin to a role-playing game than an arcade quarter-gobbler, demanding exploration, memorization, deduction, and skill. Samus' pick-ups doubled as both weapons and keys, meaning that she naturally gained the ability venture further into the hazardous depths as she built up the strength to survive the threats therein.

Perhaps not surprisingly, not a single one of these new and upcoming games attempts to offer a pure rendition of this format. Chasm and Rogue Legacy fold roguelike mechanics into their structure, including a high degree of randomness that's completely antithetical to Metroid's deliberate construction. Axiom Verge feels like a mishmash of Metroid, Contra, and a number of other NES action games. Finally, A.N.N.E. takes on an even more chimerical aspect.

"Metroid is definitely the main influence," says Breton, "but what I really wanted to do was mash some of my favorite games together and see what happens. Throw in elements from games like Gradius, Blaster Master, Mega Man, Guardian Legend, and Ys, to name a few.

"One of the elements I am bringing into the mix is physics-based gameplay. Your ship has the ability to pick up heavy objects in the environment that can be used to unblock the entrance to a cave, or as a weapon against enemies or as a platform for the character. I want the exploration to be a mix of traditional exploration (find X upgrade to access X area) and more dynamic (make your own path). It’s fun to shoot stuff up, but it’s also a lot of fun to use a bit of your brain to figure out how to reach new areas."

Similarly, Lee admits he and his brother shied away entirely from mimicking Metroid, and suggests that whatever similarities exist are more a matter of coincidence.

"We never tried to make Rogue Legacy like a Metroidvania since we knew the system we created would not be conducive to a backtracking system with door locks," he writes. "We were more inspired by the general concept of cartography, and having people map out the path that they wanted to take. Metroid is all about strict design, where you know where everything is placed and where the player is going to go at all times. You need weapon A to get to room B, and so on. But roguelikes are a lot more fluid, where you don't know where the player is going or how he or she is going to play, so you give them the tools and let them worry about it."

"I found that it ended up being a puzzle balancing the areas you visit (and re-visit), bosses fought, new abilities gained, etc," explains Chasm's Petruzzi. "They all have to tie in together, and balance where you don’t fall into strict routine, or have boss battles or power-ups gained back to back. There needs to be breathing room, while keeping things interesting. It’s enlightening seeing how Super Metroid went with just a few large areas with upwards of 30-40 rooms you continually revisit, versus how Symphony of the Night has many smaller areas that are usually only around 10 rooms and more throwaway in nature.

"Due to our limited resources, it made much more sense for us to focus on fewer unique areas, but making them more interesting by finding good reasons to bring the player back to them. We’re hand-designing the individual rooms for consistency and high quality, which brings up the question how do the procedural elements tie in beyond the dungeon layouts?"

Perhaps this complexity is what's caused Nintendo to shy away from Metroid. Like the rest of the games industry, Nintendo tries these days to cater to the broadest and most profitable audience possible, and Metroid's baroque design by necessity spurns casual and less experienced players. But moving away from the older games' labyrinthine design undermines the essential quality that makes Metroid what it is, as witnessed in the disastrous Other M.

With Other M, the team behind the classic entries attempted to create a more accessible design by stripping out the sense of exploration and focusing on action and combat in the vein of God of War and co-developer Team Ninja's own Ninja Gaiden series. What they came up with proved to be the worst-received chapter of the Metroid franchise to date, despised as much for its simplified play mechanics as for its poor handling of Samus Aran's character. Nintendo played by the rules of current-gen blockbuster design, but those rules simply aren't compatible with Metroid.

And perhaps Metroid simply can't exist as a major franchise in an industry that has deprecated complexity and freedom in favor of its new sacred cows, accessibility and universal appeal. In truth, though, Metroid's creators have struggled with the series' direction for years. Metroid Fusion underwent a radical reinvention during development. Zero Mission changed at the last minute from a cartoonish kid-friendly visual style to something more traditional (though a number of backgrounds in the finished game retained the original comic style). And then of course there's the infamous Metroid Dread, a proper Metroid sequel for DS that vanished before it was even formally announced.

Nintendo's not really a company to let valuable properties lie -- witness last year's big-budget Kid Icarus sequel after 20 years of silence -- but until the company sorts out its long-term plans they surely have bigger priorities to contend with than how to make a proper Metroid game that somehow doesn't simply seem like more of the same and yet will still make a tidy profit.

Until then, though, we can get our fix from indie developers, who tend not to be as motivated by the bottom-line perspective that drives corporations like Nintendo.

"Personally, I just try to remind myself that I'm doing this more for myself than anyone else," admits Happ. "Kind of like classical art. Maybe that's the core problem with AAA games to begin with -- there's no sense of 'we should make this because the world will be richer for it' when you have to sell like gangbusters just to keep afloat."