Did Resident Evil 4 inspire this bear horror movie?

Of all the films to take notes from Capcom's survival horror classic, we didn't expect this one.

Winnie-the-Pooh: Blood and Honey is a roaring carnival of witless bullshit. There are things in this movie which defy any sane classification: simply saying them out loud makes you seem as if you're confessing to some crime or other. At about 15 separate points during the movie, your mind will whisper ‘can everyone else see this, or have I totally snapped? Am I dead?’. In the Silent Hill 2 remake, when James finds that tape, this will be what he sees.

There’s a section with a swimming pool which is, and I’m not being over-the-top here, the stupidest thing I’ve ever seen. Pooh – PIGLET – drives a BMW Estate, which sounds mundane (where’s he going after he kills all these people, the driving range?) until you say it out loud and wonder if you’ve accidentally seen something only the crew of the Event Horizon were meant to. Go on, say it out loud. 'Pooh drives a BMW Estate'. Over someone's head, granted. Does that make what I'm saying better? WHAT ON EARTH ARE YOU ON ABOUT, MATE. See it immediately.

While you’re there, after everyone in the cinema has sliced open their thumbs into a petri dish to prove to each other, despite their life choices, that they are real people, you may begin to notice what seems like a pervasive influence on Blood and Honey: Resident Evil 4. Again, that sounds bizarre, but we’re here now. Go with it.

Ascribing intent to filmmakers is always dangerous, and should usually be avoided. History is littered with critics hanging their hats on theories and then being told it was actually budget concerns, or shooting schedules, which informed specific choices, not any overt homage. And if I’m wrong, well, that’s fine. But if Blood and Honey wasn’t meant to reference Resi 4, then I have no idea how it ended up like this.

At first, you think it’s just a coincidence. After all, it is a slasher movie, and it’s not like Resident Evil 4 wasn’t stealing from Lucio Fulci or Tobe Hooper, or that particular Friday the 13th movie where Jason hasn’t quite got his wardrobe sorted out yet and wears a bag over his bonce. And it’s not like Resi 4 invented forests either, or the fact that going into them always seems to end badly.

Then, however, you see a character do something you’ve done a million times before: smashing open a suspiciously familiar-looking crate. You know, the sort that might contain some supplies or, sometimes, a snake. When this happened, I turned to the person I was watching it with, who literally works for a video game publisher (he’s not my uncle), and said ‘did you see that?’ They did, and they thought the same. That conspicuously-placed truck (embedded above) looks familiar, as well. Hope there aren’t any Spanish coppers about.

Things escalate from there, because while sometimes a crate is just a crate, and the truck isn’t particularly egregious, it’s a little harder to explain the showdown in a barn which seems very similar to the Bitores Mendez boss fight where he transforms into whatever that thing is, complete with chains hanging down from the rafters. Many, many times during the screening I asked myself if I was imagining what I was seeing, so it wasn’t unusual to turn to my friend and ask such things, but – again – the consensus was it was very close.

Things get clearer, however, in one of the movie’s uppermost demented scenes. Up until this point, the plot has trundled along as expected. Well, not the Winnie-the-Pooh part, but still. It’s standard slasher fare: a group of young and (in some cases) intentionally underdressed women head to a house in screaming distance of the Hundred Acre Wood. Maria, the lead and ‘final girl’ is struggling to recover from her nightmarish experiences with a stalker, and so as you would expect the natural thing to do would be to get out of town and hang out in a spooky old forest.

Sadly for the women, Winnie and Piglet have (after Christopher Robin abandons them to go to uni rather than, you know, hang out with talking animals) gone mad and turned into some hybrid man-beast bonanza of bollocks. They killed Eeyore, and now they’re routinely killing people who get close to their lair. This explains where they got the BMW from, I think. I’m not sure Winnie-the-Pooh’s papers are exactly in order, but in this movie you simply can’t tell.

Anyway, once the killing really starts and the women realise they’re being hunted by the world’s greatest argument for copyright law, they panic. But wait! There’s a plan. In a scene so ridiculous that it’s obviously meant to be a joke (though none of the rest of the movie really supports it: it’s not intentionally funny apart from maybe this part), she exclaims that she has forgotten about the gun she brought with her.

There are a few things to break down here. Firstly, if my pals were being ruthlessly slaughtered and then I found out someone else in the party had a secret gun, I’d be a bit annoyed. But then I’d probably start asking questions, such as: how did you get a handgun in England? Sure, the country has its problems, but easy legal access to firearms is not one of them. Finding a gun store here is like finding a British Prime Minister who didn’t go to Oxford: difficult, time-consuming, and ultimately rather futile.

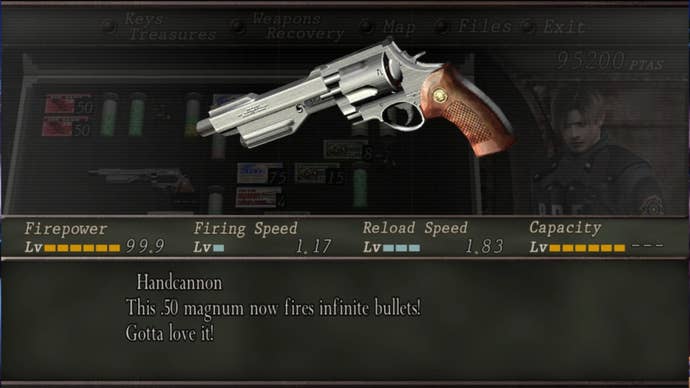

Then you see the weapon in question. Look familiar?

At this point, after I stopped laughing like a drain, I wondered if she was just really good at Mercenaries.

The similarities don’t end there, but as I was watching the film I did start to wonder about just how a new generation of filmmakers might have been influenced by the Hollywood-guided cutscenes in the games they grew up playing. After all, when people see something which is inspired by something else, or a parody or pastiche of it, that often becomes the foundation of their initial understanding of it, not the actual source. A good example of this, for me at least, is how the Tommy Lee Jones character in this gag from The Simpsons delivers the famous ‘I don’t care’ line in a much, much different way than in the actual movie: having seen The Simpsons version first, the actual delivery by Lee Jones never felt quite right.

Blocking, direction, lighting, framing, mise-en-scene (one for the beret crowd there): some of the new school of directors and DoPs seem to draw from games in how they see film, in an ouroboros-like feedback loop. Blood and Honey’s direction contains a few instances where you could take the frame out and plonk it into a game cutscene and it would just work. In a way, it’s oddly fitting, in Blood and Honey at least: there are shots with an over-the-shoulder vibe which are very Resi 4, and it’s hard to overstate just how important that camera angle was to the game’s success – and the industry as a whole – when its imitators showed up.

With the success of The Last of Us TV show – and the ongoing raid on video games IP for adaptations with a pre-baked audience – we’re likely to see more of it creep in. This doesn’t make it a good or bad thing, of course: more that it’s interesting to see a medium which was often derided for copying film finding itself influencing film. This is most prevalent in the feeling that some framing feels like you’re waiting for the cutscene to end and the camera to move closer to the characters as you take control, no doubt done deliberately here.

I wasn’t expecting to think these things after seeing Winnie-the-Pooh: Blood and Honey, but then I haven’t thought about anything else apart from that thing since I saw it. It will run forever, like The Room, and, well, you can’t argue with that.