Why is Hardship the New Hotness?

Eurogamer's Chris Donlan delves into DayZ, survival, and the glorious cult of cruelty.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

I'm always late to the party -- even when most of the people at the party are dead.

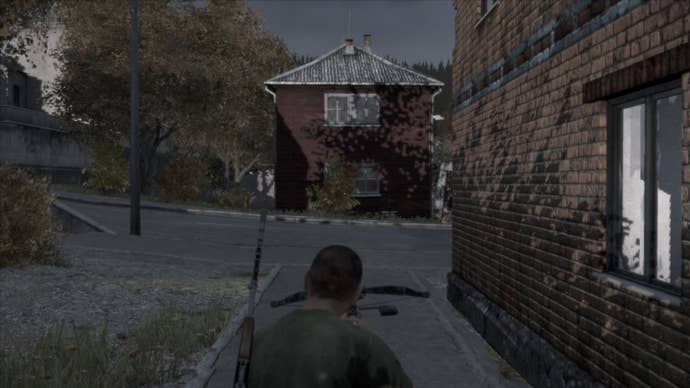

In the case of DayZ, I'm very late indeed. It's been two years since Dean Hall's mod started to turn ordinary gamers into hardened survivalists, and in that time, it feels like the game has helped cement a genre -- or something that certainly behaves like one. I get hundreds of press releases in my inbox every week, and about two thirds of them promise that the latest title I'm about to fall in love with is just like DayZ -- or just like Minecraft. These titles are not unrelated. In 2014, we love foraging and scavenging. We love finding our own tools and getting by on next to nothing. We love hardship. We love suffering. It's no longer enough to just thrive -- we want to feel the sharp edge of survival itself.

Why is this?

That's a question that's worth trying to answer, if only because these games feel so vital, and it would be nice to get some of that vitality into the rest of gaming, too. When I first dropped onto a DayZ server, for example, I just waited. I knew something awful was going to happen to me. I wanted something awful to happen to me. I wanted DayZ to kick me around, like it had kicked around all my friends. Sure enough, I didn't have to wait long.

Zombies were upon me within minutes. Blood started to spray in pretty little bursts from my head. There were 23 real people on the server that day, and I didn't see any of them. Instead, after I escaped from the zombies, I found a crossbow without bolts, a hat where the only conceivable fashion statement was, "Hey, I must have been depressed when I bought this," a moldy green bell pepper and several cans of pop. I carried the useless crossbow around because it made me feel better with regards to the hat. I ate the bell pepper by accident. The cans of pop got stuck to my hands, so I just wandered about with them, a post-apocalyptic idiot with cans in his hands. After an hour, I was clubbed senseless by a second group of zombies while trying to take an artful With-the-Beatles-style screenshot down by the wharf. A cargo crane hung overhead as the world blurred out. I hadn't fired a single weapon in anger. I'd spent most of the game exploring in near total silence. If you've played DayZ, though, you probably know what I'm about to say next: the whole experience was electrifying.

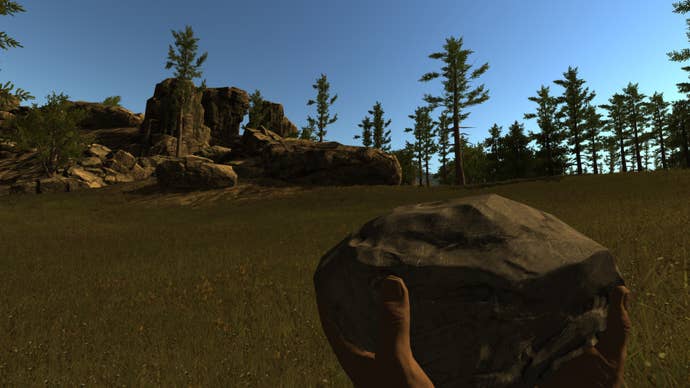

Like a lot of people, my introduction to the survival genre was Minecraft, and I didn't realise it was a survival game until night fell and I patently failed to survive. This still feels like the best way to get into these games, even one as sunny in its demeanor as Mojang's. They drop you onto the playing field with nothing in your virtual pockets, and you, ideally, respond with near-total ignorance, coupled to a child's gormless enthusiasm for the unknown. I knew nothing about Minecraft except that it had blocks in it. It was a building game! I built, and then night fell. That's when the horrors came out, and I realised that I should have been building something rather specific -- like a bunker.

You remember your first bunker in Minecraft, because it really counts. You had to overcome stuff to create it, and its design is, initially at least, defined by the things you've learned, often painfully. This is a huge part of the appeal of survival games wherever they lie on the spectrum, I think. Plenty of games are creative, but survival games provide a context that forces you into creativity. They're LittleBigPlanet with a gun held to your head. In something like DayZ, you quickly start inventing off-the-wall strategies for handling encounters -- or avoiding them entirely. In something like Minecraft or Terraria, you transform that first frantically cobbled-together bunker into a fortress, or a palace. A fox-hole can become a proper underground lair in a matter of days. Avoiding death leads to aesthetic concerns.

Ah Terraria! I've had plenty of fox-holes in Terraria, as it's probably the survival game I've played the most. Unlike games such as DayZ or Rust, it presents a cheery face to the world. It doesn't look like it's going to grind you down before you can start to build yourself up again.

Don't be fooled, though: Terraria's as cruel and as devious as any of the other survival games out there. It allows you to acquire astonishing things, but it forces you to venture underground to get most of them, and down there with the flickering torch shadows and collapsing sand, it has you at the mercy of its terrifying menagerie.

That's another part of the puzzling appeal of survival games, really. Survival games present systems -- often even complex systems - that fundamentally make sense. It's a very specific kind of sense I'm talking about, mind. I don't really know why there's always a stronghold at one side of the map in Terraria, and why there's always an island floating in the sky somewhere else, but the mere fact that there always is allows me to build the information into my moronic plans.

Perversely enough, the systemic rigor of survival games then allows for moments of real, blood-pumping wildness. So many predictable pieces going about their horrible businesses creates brilliantly unpredictable outcomes that still have just enough internal logic about them to keep them honest and interesting. It's delicate stuff, chaos. If the zombies randomly spawned throughout the entire day in Minecraft, the tension wouldn't be quite the same; it's actually more frightening to see fewer of them. To truly dread something in a game, I think, you have to have a decent sense of when and where it's likely to happen to you. You have to have small islands of safety. Otherwise you just have panic, and panic is fun for a short period, but over time I tend to tire of it. There's no surviving prolonged panic. I just get annoyed and load something else.

Slow-burning dread? That sounds like a tricky sell, and when you couple it with instant death and the fact that you'll need to put in lots of hard work to get anywhere, it can be hard for an outsider to see not only why these games are so popular, but why they've captured the imagination of a new generation of gamers -- the kind that grew up with Minecraft rather than Mario, the kind that reads The Hunger Games books and pumps hundreds of hours into DayZ every month.

The part of me that sits in wingback armchairs while underlining amusing sentences in the Times Literary Supplement and clinking a teaspoon thoughtfully against my elegant front teeth is tempted to spin some kind of socio-economic theory out of this, actually. Something about how a generation that's grown up in a recession and is likely to enter a miserable job market is priming itself through play for the deprivations ahead. Educating Chernarus. When the best you can hope for, if the news media is telling it straight, is decades of student debt and a working life spent asking people if they'd like sprinkles on that, you probably don't want to go home at the end of the day and be smacked around the face with the rim-lit wonders of the Mushroom Kingdom. In this theory, DayZ had less to do with Dean Hall swallowing some dodgy ramen on a training course in Brunei and wondering if we'd all like some too, and more to do with Bear Stearns and toxic assets and politicians working so hard on fixing the economy that they're reduced to eating expensive burgers at their desks. (I wonder if they'd like sprinkles on that.)

Play something like DayZ for an hour or two though, and it's hard to avoid the conclusion that this theory could only ever account for a small part of the phenomenon. Why wouldn't you like games like DayZ, like Don't Starve, like Rust, which are punkish and professionally half-finished? Many of them use their moody basins of mud and wet turf to provide brilliant social commentary as player meets player, transforming scarcity and violence into prime-time displays of human behaviour that are by turns comic and poignant. Most encounters in survival games are so charged by the air of twitchy distrust and vulnerability that they spawn one-off set-pieces that you'll remember for months. The end result is either pratfalls or a Haiku.

If survival games are a response to anything, in fact, it's probably something much closer to home. Shamelessly rough and daringly formless, these hike-'em-ups, plant-'em-ups and barricade-'em-ups feel like a creative rejection of the kind of mindless cinematic over-scripting that defines series like Uncharted. Survival games don't need to treat the player like an actor who'd better hit his marks or else, because they don't need to have you pointed in the right direction to see the next mega-budget cut-scene. They're not trying to be movies or even TV. They're trying to be YouTube videos and livestreams. They're voodoo documentaries that no normal channel would be able to air. Instead of creaky matinee trickery, you get the landscape, the atmosphere, and often dozens of other players, as starved and as half-mad as you probably are. You get the scope for inventive griefing, for mocking executions from afar and for human nature left to explore its most creative capacities for selfishness. Now that's a video game.

Because of all this, there's the tang of illicitness to survival games, whether or not they're mods or prolonged alphas -- and this only makes them even more appealing. Their worlds are frequently glitchy and haunted. There's the clear sense that you probably shouldn't be there, and who can resist exploring a place where they shouldn't be? Don't Starve is particularly good at this kind of thing. Beyond the Biro-doodling of the character designs and the disconcertingly hearty soundtrack lies a game in which absolutely everything wants to kill you. It should really be called, Don't Starve or Set Yourself on Fire or Freeze or be Eaten by those Weird Trees with Mouths. Maybe the domain had already been taken.

In amidst the keeling over and the losing your mind and the going up in smoke, though, Don't Starve's survivalist purity allows you to glimpse a final deeper truth, too -- a truth that holds for DayZ and for Minecraft and for everything on the spectrum in between. Survival games are about acquisition and about progression as much as they're about anything else. Like an old-fashioned RPG, they're about improving your kit and building your resources, and the only difference is that your treasured trinkets are clumps of grass rather than magical boots, and that the tankards of frothy beer have been swapped out for berries that looks like somebody's sat on them. Oh, and that you can lose everything in seconds. Or gain everything. Don't Starve will make you bow and scrape and toil before a bonfire all the rainy night long to keep that feeble flame burning, but games like this can make you truly feel as rich as a king come morning, too.

And, as is always the case with games, the road to becoming king starts with looking beyond the rules and learning the deeper rituals. Two years on and DayZ is no longer alone: it's helped shape the genre that continues to thrive around it, and with that genre now comes best practices and standard implementations and a recognisable interface and the soothing whisper of familiar beats.

This is perhaps the most contradictory thing about the grim realities of the survival game, where a life is cheap but a can of beans can be worth a fortune. When you know what it is, and when you know how it works, for all its brutalities and indignities, a survival game can becomes perversely comforting. To many people, DayZ, with its horrors, its harshness, is a kind of home. And people will do anything to protect their homes.