Why Dragon Quest Failed to Make it In America 30 Years Ago

Nintendo tried its best to make the West love RPGs, but culture—and more importantly, timing—was against the attempt.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

Dragon Quest is 33 years old. Like the mythical creatures it takes its name from, the role-playing game series has become bigger and wiser in its passing years. It's grown from a simple adventure where a legendary hero slowly trades blows with monsters to an epic that travels through an enchanted world for dozens of hours.

But it takes effort for a fantasy protagonist to build themselves up from a stick-swinging slime-slayer to a grown warrior who's fully outfitted to fight scourges that slither up from the deepest pits. Dragon Quest had a slow start in Japan, but it picked up tremendous steam after its publisher, Enix, promoted the game in Japan's widely distributed Shonen Jump magazine. When Nintendo of America prepared to release the localized version of the game—exactly 30 years ago this month—it immediately ran large-scale promotions in hopes of getting North Americans to fall in love with RPGs as hard as Japan.

Despite Nintendo's efforts, Dragon Quest—which became Dragon Warrior in the West because D&D publisher TSR held the rights to the Dragon Quest name at the time—hardly caught fire in North America. Though a handful of kids certainly fell in love (the author of this piece included), Dragon Warrior generally sank to the bottom of NES owners' libraries and was buried under the deluge of Super Mario, Mega Man, and Castlevania games available at the time. Nintendo tried its best to make us love Dragon Warrior, and it failed. This is where Homer Simpson might suggest the solution is to "never try," but Dragon Quest has fortunately found itself a dedicated Western audience since its Shockmaster-style 1989 debut.

Looking back on Nintendo's push, it's not hard to understand why all those Dragon Warrior cartridges wound up languishing in living rooms. Cultural differences between Japanese and North American audiences contributed to the disinterest, but time was simply not on Nintendo's side, either. By the time Dragon Warrior came Westward, Japan was already enjoying its enormously improved third installment, Dragon Quest 3. Novel as it was, Dragon Warrior was already arcane and dusty by the time it arrived, and Western audiences just couldn’t get excited when much flashier games like Super Mario Bros. 3 were on the horizon.

"Please Give This RPG a Good Home"

No one can begrudge Nintendo an "A" for its efforts to get us excited about Dragon Warrior. Its plan of attack was threefold: It updated the game's visuals during the localization process, it promoted the game like mad in its Nintendo Power magazine, and finally, it just gave us the darn game for free. Dragon Quest was a phenomenally popular series in Japan when Nintendo started promoting Dragon Warrior on these shores (Dragon Quest 4 was already in development overseas), and Nintendo likely hoped we'd be inspired to buy the sequels after we ate up the free sample.

In retrospect, it's worth wondering how long it would've taken Nintendo to localize Dragon Warrior 2 and 3 in an alternate universe where Dragon Warrior did become hugely popular. Even a Mario game's localization took a good deal of time in the pre-internet age, let alone a game with pages of text.

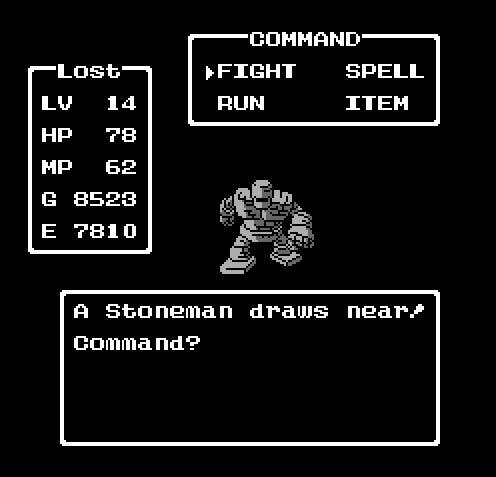

The first clue about where Dragon Warrior "went wrong" can be identified in Nintendo's decision to upgrade its graphics. The first Dragon Quest is a very primitive-looking game—the player character doesn't even face the direction he's moving in (he received a whole new set of sprites for Dragon Warrior)—but even with the spit-shine, Dragon Warrior is still far from a showcase of impressive visuals. The monster designs by Dragon Ball Z manga artist Akira Toriyama are very charming, but outside of enemy encounters players spend a lot of time staring at squashed character sprites and plain overworld maps.

"The original Dragon Quest was very much a 1986-vintage NES game, and its age showed, even with its improved sprites and slimmed-down menus," writes Retronauts' Jeremy Parish in a blog. "The game's primitive tile-based graphics, heavily windowed interface, and sluggish movement would have been less detrimental when every game looked like that. But in 1989, we had gorgeous action games like Mega Man 2."

Nintendo had a hard time getting Westerners to fall in love with Dragon Warrior, but at least it didn't have a hard time getting the game in their hands. It sent out a wonderfully-illustrated mailer that promised a "monstrous" deal for 7.5 million prospective Nintendo Power subscribers. This obviously wasn't a small job for Nintendo: Mailing out the promotion itself was such a huge ordeal, the employees working at Nintendo Power's distribution warehouse even printedT-shirts declaring "I Survived the Dragon Warrior Mailing." "Once the job started, it continued for 19 hours every day, seven and a half days in a row," states a Nintendo News Pak corporate mail piece from November 1990.

Unsurprisingly, kids saw the offer and said, "Free game? Hell yeah, sign me up," after checking to make sure their parents weren't in the room to hear them say "hell." Dragon Warrior arrived as promised, the kids shrugged after a few hours of play, and the rest is Dragon Warrior history.

Not a Pretty Picture

To reiterate a previous point, Nintendo's Dragon Warrior localization is built on a three-year-old game. This can't be overstated, because it ties into another important reason the debut game failed in North America: Japan initially wasn't too impressed with the first Dragon Quest game, either. It only caught on thanks to a campaign laser-focused on its target audience.

"Dragon Quest released in February 1986. The Enix team panicked when the game hardly sold. It began advertising in Shukan Shonen Jump, a weekly boys' magazine with a circulation of 4.5 million copies," David Sheff wrote in 1999's Game Over -Press Start to Continue: The Maturing of Mario. "The magazine's editors agreed to publish an article about the role-playing game's lore and mythology. It sparked Dragon Quest sales; a groundswell followed."

The first Dragon Quest should be recognized and appreciated for revolutionizing console RPGs. But to be honest, it's not much fun to play anymore.

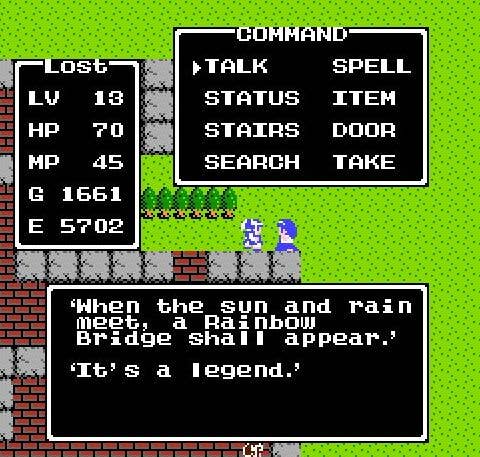

Dragon Quest 3, which hit Japan almost a full year before the West received its free copies of Dragon Warrior, is fun to play, even all these years later. It's a huge adventure filled with interesting subplots, puzzles, and even town-building. Players get to build up their own parties from a selection of classes, then engage in quick-paced battles against regular monsters as well as vicious bosses. The soundtrack is one of the series' best, and the Dragon Quest 3 overworld music is probably remixed for modern Dragon Quest titles more than any other piece. The graphics aren't remembered as the NES' best, but they're much improved over the first game and include interesting new environments.

That's all on top of significant quality-of-life improvements over the first game, like no longer requiring torches to explore caves and pressing "A" to chat with townspeople in lieu of selecting "Talk" from the menu every time.

In hindsight, Nintendo might have had more success getting Westerners interested in Dragon Warrior 3 instead of Dragon Warrior's uniformly pitch-dark dungeons and ponderous one-on-one battles. Nintendo's hard work promoting Dragon Warrior was admirable; it just backed the wrong game. Dragon Warrior 3 did indeed make it to the West, but not until 1992—long after the NES was old news next to the Super Nintendo.

Two Cultures, Two Different Methods of Dragon-Killing

Even if Nintendo spent its time, money, and effort localizing and distributing free copies of Dragon Quest 3, cultural differences between Japanese and North American gamers might still have prevented the translated game from touching Japan's sales numbers.

RPGs certainly had an audience in North America—series creator Yuji Horii's inspiration for Dragon Quest stemmed from his interest in Western-developed RPGs like Wizardry, after all—but that audience was primarily found on computers. The NES' best-sellers were platformers and action games like the Super Mario Bros. titles, Mega Man games, and Contra. Look at the game list for the NES Classic if you want an idea of what North American childhoods were made of: Ninja Gaiden, Super C, Ghosts 'N Goblins, and so on.

In other words, the NES generally meant "action," and games with the leisurely pace of Dragon Warrior didn't occupy as much shelf space in Toys 'R' Us. It's not surprising that the kids who played those free copies of Dragon Warrior generally walked away from the experience feeling confused.

Moreover, dying in Dragon Warrior is a punishing ordeal. You're sent limping back to the game's starting point with half your gold, which is a major deterrent for players who just want to push ahead and see what's on the horizon. Other old school NES action games are also brutal, but they usually offer a straight shot to success via instantaneous power-ups and extra lives. In Dragon Warrior, the only way to get strong enough to defeat the Dragon Lord is by slowly and steadily building yourself up. You fight Slimes for scraps of gold, which you use to buy slightly more powerful weapons. Once equipped, you can take on the next tier of enemies and win more gold. It can take hours to get strong enough to beat the Dragon Lord.

"That's a very traditional thing for [Japan]. You have to try, try, try, try—and then at the end you can finally get a reward," Yuji Horii tells Gamasutra in a 2011 interview. "It's like climbing up a steep mountain—you have to keep climbing, climbing, climbing, climbing, and then at the end you finally get to the top of the mountain, and you see the beautiful view."

That's not to suggest NES owners detested RPGs. The first Final Fantasy, which Nintendo also published, sold over 700,000 copies. In fact, it's the only menu-based RPG included on the NES Classic nostalgia machine. Those numbers still aren't on the same level as the millions of copies Dragon Quest moved in Japan. But Final Fantasy has flashier graphics and a more sophisticated battle system than Dragon Warrior; maybe its better reception affirms that Western audiences might have reacted more positively to a Dragon Warrior 3 promotion.

As influential as Nintendo is in gaming, even it lacks a "Reset" button that might let it return to the '80s and give its Dragon Warrior stunt another try. It'll just have to be content with the definitive edition of Dragon Quest 11 being a Switch exclusive. That's not so bad.

Header art via The Cover Project

Screenshots via MobyGames