Why Did Atari Fail in Japan?

30 years ago, Atari made its official debut in Japan, hoping to go toe-to-toe with upstarts like Nintendo and Sega. It bombed hard.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

Until Nintendo waded into the fray and sorted things out with its iron-clad rule, the Japanese home games market muddled along somewhere between "anemic" and "chaotic." Unlike the American market, no single platform had risen to dominance in Japan's console scene before Nintendo joined the battle. In fact, Japan barely had a console scene until the Famicom, MSX, and SG-1000 debuted in July 1983.

"There wasn't much of a home console market," agrees Magweasel editor and game history expert Kevin Gifford. "Epoch's Cassette Vision de-facto monopolized that market in Japan from 1981 to 1983, and even that was chiefly because it was cheap compared to the imported competition."

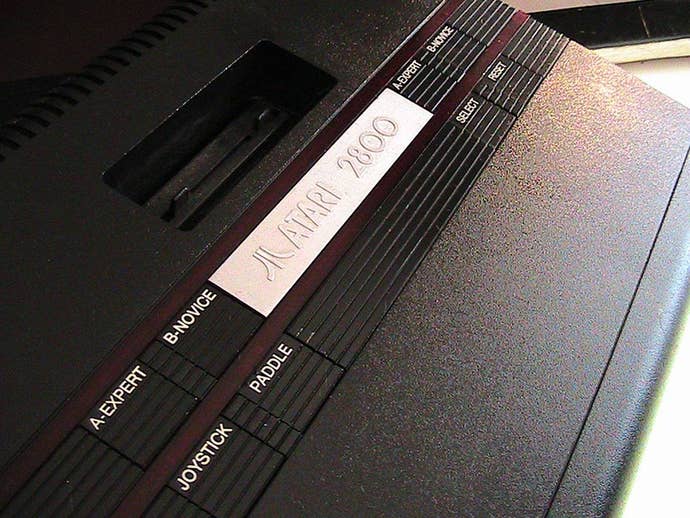

The missing ingredient in Japan's early console mix? Atari's VCS, better known as the Atari 2600. The undisputed console juggernaut in America for more than five years, Atari's revolutionary system has gone down as little more than a tiny blip in Japan, where it launched under the name Atari 2800. You'd be hard-pressed to find any trace of the console in Tokyo's well-stocked retro game shops; aside from a single pricey console in a banged-up box that's been collecting dust on the same shelf at Akihabara's famous shop Super Potato for the past few years, I've never once seen Atari 2800 merchandise in Japan. You can even find Intellivision software pretty easily if you know where to look, but good luck finding its chief rival in a country where classic games are practically commoditized.

What happened? Why did Atari blow it so badly in what would prove to be one of gaming's most pivotal markets? Ultimately, their failure boils down to three factors.

Problem 1: Terrible timing

When Atari 2600 launched in America in 1977, it changed the entire concept of console gaming as it had existed to that point. To be sure, it wasn't the first system to pull off any of the technical feats for which it's known; the Fairchild Channel F had introduced the concept of games stored on interchangeable cartridges to liberate the machines from the shackles of expensive dedicated hardware in 1976, and various Pong clones (such as Nintendo's Color TV Game 6) beat it to the punch for color graphics. What Atari managed to do was bring together flexibility, extensibility, power, and quality software for a great price; it towered over the competition of its day. By the time Mattel managed to roll out the Intellivision in 1979, Atari already had the advantage of a massive lead. The competition -- technically superior though it may have been -- never stood a chance of catching up.

Perhaps if Atari had released the system overseas in 1979 or 1980, the 2800 might have had a shot.

Yet a number of factors kept Atari's machine from making its way across the Pacific in a timely fashion. Blame it on the nature of an industry in its infancy. Blame it on the fact that Japan was still establishing itself as a global electronics leader. Blame it on the high cost and high risk of exporting bulky goods to an untested market. Whatever the case, the 2600's Japanese counterpart, the 2800, didn't make its debut until fall of 1983.

"Although various companies like Epoch had imported and distributed the 2600 in Japan, it was never officially supported nor was it heavily promoted," states an uncredited Atari 2800 retrospective at Freelancer Games. "Perhaps if Atari had released the system in 1979 or 1980, the 2800 might have had a shot."

"They were a bit late to the game with it," writes Sean of Famicomblog, "releasing it in 1983 just as the Famicom was about to hit. That meant it was a total failure in a commercial sense and they only sold a handful of them."

In fact, the 2800 came to market shortly after the Nintendo Famicom. In 1983, the U.S. console market had already begun its infamous implosion; by that point, New Mexican bulldozers were revving up to crush surplus E.T. cartridges into landfill pulp. Atari found itself with far more pressing concerns to worry about than marketing an aging console in a tiny country half the world away, and less than one-tenth of the more than 400 titles officially released for 2600 ultimately made their way to 2800.

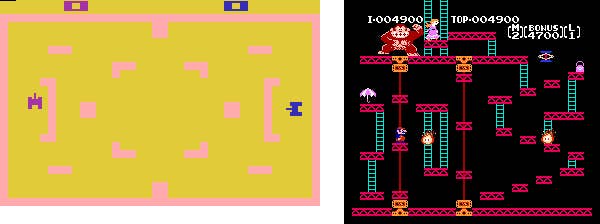

While the 2800 had more games at launch than the Famicom -- Nintendo made only three titles available on day one, with a total of nine games released by the end of 1983 -- the newer system's software seemed light years ahead of the 2800's dated offerings. One needed only compare each system's take on Donkey Kong side-by-side for a clear sense of how badly Atari's machine was outclassed by Nintendo's console.

"Next to the Family Computer, games on the Atari 2800 must have looked practically archaic," wrote Frank Cifaldi in a 2800 retrospective on 1UP. "The architecture in the system was already six years old by that point. That, perhaps combined with the system's American origins, meant that Japanese gamers would flock instantly to Nintendo's system, leaving the 2800 to collect dust on store shelves."

In fact, the 2800 was a generation behind even for Atari; it contained the guts of the 2600, which had been surpassed nearly a year prior by the Atari 5200. Meanwhile, the 7800 (which ran on a chip remarkably similar to the Famicom's at the exact same speed) was lurking in the wings for a U.S. launch half a year later. In one of gaming's most fascinating might-have-been moments, Nintendo actually approached Atari as a possible partner for the U.S. distribution of the Famicom, presumably unaware that the company was preparing its own direct competitor for what would become the NES. Had Atari not been putting out fires on its home front and bracing to be cut loose from the Warner mothership, one can only imagine that they would have jumped at the chance to grab the rights to the NES simply to sit on them and suffocate the system in favor of the 7800.

Problem 2: Unreasonable price

Looking back at the Japanese games industry of 1983, Gifford notes, "There was a definite opportunity for a Japanese manufacturer to bring home console technology to the next level at a price that importers like Mattel and Atari couldn't match, and that thought is likely exactly what brought [NCL President] Hiroshi Yamauchi to launch the project that became the Famicom."

There is no way the Famicom could've sold 1.4 million systems in its first year -- and that's with just a dozen or so games, too, and no third parties -- if it wasn't for the bang it gave for the buck.

Price was everything to Nintendo. Yamauchi pushed the Famicom's chief hardware designer, Masayuki Uemura, to create a system that offered unrivaled technical power for the lowest possible price.

"There is no way the Famicom could've sold 1.4 million systems in its first year -- and that's with just a dozen or so games, too, and no third parties -- if it wasn't for the bang it gave for the buck," says Gifford. "Yamauchi's only real order to Uemura and team was to make the system as good as possible, for as cheap as possible. There are echoes of [Commodore founder] Jack Tramiel in that: 'Computers for the masses, not the classes.'

"The Atari 2800 was not released until 1983, the same year as the Famicom, for the ridiculous price of 24,800 yen. Compared to the 14,800 yen price tag of the Famicom, which was substantially more powerful for a lesser cost, it's easy to see why it had no real chance. And that's not even taking into account the fact that neither competitor had any big software support.

"The difference in quality between the two are pretty obvious," muses Gifford, adding that Atari's troubles were further compounded by the fact that Sega's SG-1000 launched the same day as the Famicom for the same price. Granted, the SG-100 lacked the horsepower of the Famicom, but its architecture was almost identical to that of the ColecoVision, at the time the most powerful console on the U.S. market.

By comparison, Gifford adds, "the Intellivision's list price was 49,800 yen in 1982 -- roughly $500 adjusted for inflation -- and for that kind of money you were already well on your way to purchasing a computer."

In short, Atari showed up late to the fight, wielding an overpriced expensive knife, only to find the battle dominated by cheap handguns.

Problem 3: Cultural incompatibility

And one final possible reason the Atari 2800 fizzled, though one that's much more nebulous and harder to prove than hard numbers like pricing and launch date: It simply may not have been the right system for Japan.

By 1983, you could already tell at a glance if a game originated in the U.S. or in Japan. While the medium came to life in America, Japan had proven itself a powerhouse with a rapid succession of hits, beginning with 1978's Space Invaders and continuing through instant classics like Pac-Man and Donkey Kong. Even less popular titles such as Dig Dug or Frogger had a certain feel to them that set them apart from their American counterparts. They were more colorful, more cartoonish, more whimsical.

American marketing pushed the realism of graphics; personalities as varied as actor William Shatner and political pundit George Plimpton raved about the "life-like" graphics of the Vic-20 and Intellivision, respectively. American-made games strived for realistic design and details as much as was possible within the barebones technology of the late '70s and early '80s, with much of Atari's library (and even third-party games like Pitfall!) featuring stickmen protagonists with proper human proportions.

While U.S. designers gave us the spindly avian knights of Joust, the realistic bugs of Centipede, and the abstract battle croissant of Tempest, their Japanese counterparts gave us Mappy, Pooyan, and the mustachioed stars of Track & Field.

Japanese designers, on the other hand, aspired to create personality within their games, realism be damned. The space invaders looked like seafood rather than the hulking electric Chewbaccas depicted in the cabinet art; Pac-Man was chased around by monsters whose big eyes did more than give them personality, they offered a clue to the creature's behavior; and squat Mario, of course, wore suspenders and a mustache to better define his appearance. While U.S. designers gave us the spindly avian knights of Joust, the realistic bugs of Centipede, and the abstract battle croissant of Tempest, their Japanese counterparts gave us Mappy, Pooyan, and the mustachioed stars of Track & Field.

A quick glance through the 2800's official library reveals Atari pinning its hopes not only on old games, but also on games that highlighted the aesthetic gulf between American and Japanese software. The bulk of its lineup featured simple, abstract, sometimes starkly geometric graphics. Even its handful of converted Japanese arcade titles like Space Invaders and Pac-Man lacked a hint of the originals' charm.

By comparison, the systems that launched immediately preceding the 2800 -- Nintendo's Famicom, Sega's SG-1000, and the MSX computer standard -- possessed much higher graphical standards that allowed the warmth and personality so intrinsic to Japanese arcade games to shine through. Despite being slightly compressed due to the shift in screen orientation, Nintendo's rendition of Donkey Kong felt wonderfully faithful to the coin-op, and even the more primitive SG-1000 still managed to bring home recognizable versions of Pop Flamer and Congo Bongo.

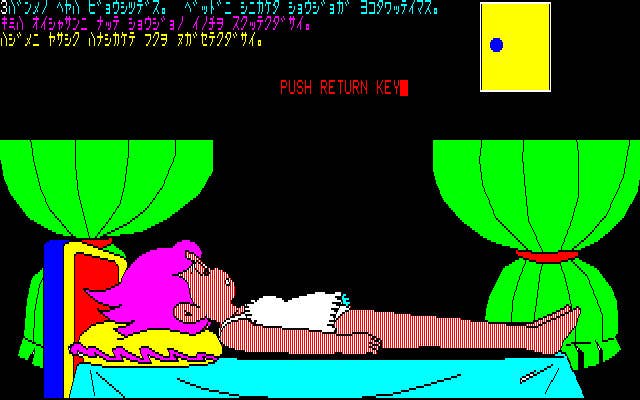

These differences weren't restricted to arcade and console games, either. For example, while American PC game designers were dabbling in adult bondage with Leather Goddesses of Phobos and Softporn Adventures, companies such as Enix were appealing to Japan's love for the cute side of kink with the likes of Lolita Syndrome.

While this could be boiled down to a simple argument of graphical power, that would be overly reductive and fail to take into account the intangible stylistic preferences and tastes of two different cultures. Those differences define their respective markets today, but they've always been present, even when graphics were so simple you could barely make out the details.

In the end, Atari badly misaimed and mistimed its official entry into the Japanese market. Maybe it could have followed through and gained some ground under different circumstances, but as profits plummeted in the U.S. the Japanese market surely seemed like a trivial concern. And even if Atari had embarked on its Japanese venture sooner, pricing and content would have presented considerable hurdles. As it was, Atari's long absence from Japan simply made things easier for the local powerhouses when they stepped in for their own attempts at locking down the console market.

Next: Nintendo Gets Into the Game