Where Final Fantasy Went Wrong, and How Square Enix is Putting It Right

Final Fantasy's star has lost its shine for many fans. We speak with the series' creators to learn how they're working to restore its former glory.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

Yoshinori Kitase has a mission: He wants to restore the Final Fantasy series to its former glory.

Granted, he's never stated his goal in so many words, but it's become clear from his comments to the press as well as my own interactions with him over the past year or two that the series' fading popularity – especially in the West – weighs heavily on his mind. And it's something he aims to correct.

A few days before this year's Game Developer's Conference kicked off, I met with the long-time Final Fantasy producer and found myself slightly taken aback by the directness of our conversation. The plan for our meeting, I had assumed, was that I would interview him about the HD remakes of Final Fantasy X and X-2, whose U.S. versions were launching a few days later. Instead, he ended up asking most of the questions.

Equally surprising was his greeting, as he began our conversation by thanking me warmly for USgamer's review of Lightning Returns: Final Fantasy XIII. Granted, our review of Lightning Returns came in toward the high end of the Metacritic aggregate, but it wasn't the highest critical rating by far. Not only that, but our text was decidedly blunt in its criticism of the game's weaknesses. I referred to the story as "dumb" and the visuals as "a hot mess," while Pete dinged it for its "clunkiness" – not really words you'd expect to inspire gratitude. As Kitase spoke, though, I began to realize that our frankness was precisely what he appreciated about the review.

What was meant to be an interview was quickly turned on its ear as Kitase reversed the usual interview format. Could I expound more on my Lightning Returns criticisms, he asked? What makes for a good Japanese-to-English localization? What do Americans look for in RPGs? How had Final Fantasy XV's trailer been received? And so on, for more than an hour.

And there were more intriguing questions, such as the "strictly hypothetical" inverse of his musings at last year's E3 about the place of turn-based RPGs on modern consoles. Would fans be OK with a remake of a classic game like Final Fantasy VI or VII, he wondered, if it changed the original game's combat system to a more action-oriented style?

The overall impression Kitase gave was that of a man taking a long, hard look at a difficult situation and welcoming all feedback, both positive and negative. As the key figurehead for the Final Fantasy series, he knows the games he creates have to change in order to recapture the international successes they enjoyed a decade ago. Right now, he seems to be contemplating what form that change must take.

Perspective

My conversation with Kitase took place just a few days after the NPD group had released its sales figures for February 2014. Relevant to our meeting was that fact that while Lightning Returns ranked in the top 10 games for the month, it had been outperformed by Bravely Default, another Square Enix RPG. The discrepancy clearly had caught the company off-guard, if the uncomfortable silence that settled over the table when Kitase mentioned Bravely Default served as any indication.

Bravely Default started life as Final Fantasy. Silicon Studio first conceived it as their sequel to 2010's DS spin-off Final Fantasy: The 4 Heroes of Light, but they decided along the way to drop the name and allow the game to strike out in its own creative direction. Despite this shift, Bravely Default nevertheless feels every inch a classic Final Fantasy title, from its turn-based combat to its mutable Job system to the way its storyline echoes Final Fantasy V's. Yet Square Enix declined to publish the game in the U.S., leaving it for Nintendo to pick up – typically a sign of little confidence in a game. Understandably, perhaps; Bravely Default is a turn-based, handheld RPG with cutesy characters designs, ostensibly a losing combo in the West. Certainly that formula didn't do any favors for 4 Heroes of Light, which sank like a stone in the U.S. in 2010, and that game still benefitted from bearing the Final Fantasy name. Could Bravely Default have been expected to fare any better?

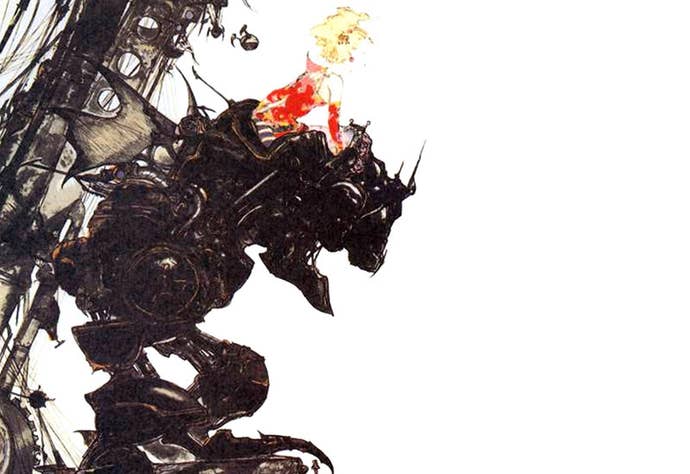

Critical Hit: Final Fantasy VI

1994, Super NES

Yoshinori Kitase's first Final Fantasy project as lead, the third and final 16-bit Final Fantasy may not have sold on the level as later games, but it can make an even more impressive claim: It's almost universally loved. Thanks in large part to Kitase's memorable scenario contributions – the opera sequence, Celes' heartrending tale, and more – FFVI managed to transcend the limitations of its primitive technology and speak to gamers, creating a generation of RPG fans in the process.

Yet fare better is precisely what it did. No doubt appearing on an ascendant platform (the 3DS) rather than being shackled to a system in steep decline helped – both 4 Heroes and Lightning Returns alike showed up on moribund platforms, which couldn't have done their sales any favors. Maybe the appealing polish of the visuals overrode any repellant cuteness they might possess. Or perhaps Americans were simply eager to play a great classic RPG, a format that's all but dried up here in recent years. Whatever the case, the takeaway was the same: A heavily promoted Final Fantasy sequel failed to outperform an estranged and deprecated spinoff.

Kitase knows first-hand that Japanese RPGs can appeal to the West. He's personally responsible for helping to prove Final Fantasy's potential for global appeal; the first three games he directed – Final Fantasy VI, Chrono Trigger, and Final Fantasy VII – may actually be the three most beloved Japanese RPGs ever published in America. Certainly they rank among the best-selling. Several of his other projects (including Final Fantasy VIII and Final Fantasy X) topped the charts abroad as well. No doubt he hopes to capture that level of success again, though of course Final Fantasy can't rely on its old tricks to stay on top. Final Fantasy VI happened 20 years ago, and both games and the industry surrounding it have changed radically in that time.

In fact, therein lies the root of Final Fantasy's current travails.

The obsession

"We had an unhealthy obsession with graphical quality."

Naoki Yoshida's confession during his GDC panel a few days later was, in its own way, as surprising as Kitase's comments had been. This time, the surprise came from his frankness. Japanese game developers tend to be fairly guarded with their self-criticism, not so much from hubris or lack of self-awareness, but more from a cultural reluctance to throw their peers and collaborators under the bus. Despite Yoshida's circumspection during his GDC presentation, however, the fact was that he spoke harshly of someone else's game project in making his point.

But then, Yoshida's strength comes from his pragmatism – his willingness to take a realistic look at the situation and do what's needed to make things work, even if it breaks protocol. As the director and designer on Final Fantasy XIV: A Realm Reborn, Yoshida has shouldered the unenviable task of salvaging Square Enix's most potentially disastrous game ever. The original version of Final Fantasy XIV was, by every metric, an unmitigated failure of an MMO. A Realm Reborn, the first of what evidently will be many stem-to-stern overhauls of the game, threw out nearly everything present in the original version and somehow turned a flaming wreck into one of the best-received MMOs of the past few years. Even more impressively, Yoshida's guidance and his heartfelt candor with the player base helped maintain confidence in the project during the lull between FFXIV's shutdown and A Realm Reborn's launch.

Critical Hit: Final Fantasy VII

1997, PlayStation

By far the most commercially successful single-player entry in the Final Fantasy series, FFVII built on the principles laid down by its predecessor – flexible play mechanics, tremendous character empowerment, a grand and apocalyptic plotline – and applied state-of-the-art visuals. It was the first console RPG to become a true international blockbuster, and it established both Final Fantasy and the role-playing genre as mainstays in the West.

Yoshida credits A Realm Reborn's success in part to his own willingness to abandon the typical hierarchy and collaboration that comprise Square Enix's development processes. He began working on A Realm Reborn by single-handedly establishing more than 400 design goals before slowly delegating tasks to a handful of trusted team members. Yet despite this unprecedented approach, he comes across as wholly matter-of-fact; there's no rancor in his criticism of the game he had to salvage, nor is there braggadocio in his explanation of his own methods. Rather, Yoshida makes it clear that FFXIV's failure wasn't the fault of any one individual but rather amounted to a systemic failure.

According to Yoshida, Square Enix's corporate and creative culture franchise fed the flames of XIV's failure. Processes that worked magnificently in previous game generations – including those that helped make FFXIV's predecessor, Final Fantasy XI Online, the company's most profitable product ever – broke down amidst the realities of the contemporary game technology and requirements. Insular designers failed to account for the changing needs and expectation of players. Artists poured excessive detail into incidental in-game objects, as Yoshida demonstrated by showing off a simple barrel in the scenery that contained the complexity of (and demanded the processing resources of) a player character – a woeful waste of human and CPU effort.

"Final Fantasy XI was successful, so the expectations for FFXIV were high," Yoshida said. "Yet leaning too heavily leaning on a previous success caused failure." The team was unable to recognize the ways the MMO market had shifted in the eight years between FFXI and FFXIV, he explained. FFXIV needed to break from the company's long-running obsession with graphics, adapt to genre-wide design changes, and respond to changes in user needs.

You can draw a line from Yoshida's comments to the franchise as a whole.

Keeping pace

In a way, Kitase's Final Fantasy VII bears much of the blame for FFXIV's troubles. Back in 1997, Squaresoft's first PlayStation RPG set a new standard for visuals and presentation. While the rest of the industry muddled along with Siliwood-style full-motion video cut scenes starring D-grade acting, FFVII featured more than half an hour of computer-rendered sequences that reflected the game's graphical style, seamlessly merging gameplay and movie. It set a new standard for storytelling; other games had used similar techniques, but never to such an extent. Never so carefully integrated into the game action. And never for a game with such depth and content. Appropriately, FFVII became Squaresoft's best-selling game, moving more than 10 million units and inspiring a number of spinoffs, prequels, and sequels across multiple media.

The rest of the industry immediately set about imitating and improving FFVII's techniques. Works like Metal Gear Solid took a major step forward by abandoning full-motion video and rendering their cut scenes with the same real-time graphics present in the game itself, creating a more consistent and immersive narrative style. At the same time, pure action games increasingly began to incorporate more and more role-playing elements.

Critical Hit: Final Fantasy XI

2003, PC/PlayStation 2/Xbox 360

Though less widely played than FFVII, FFXI stands as Square Enix's single most profitable product ever thanks to its longevity and the ongoing fee structure of the MMO sales model. FFXI started rough but grew progressively more enjoyable through years of updates and refinements – great for fans, but bad for FFXIV. According to Yoshida, the fix-it-in-the-patch mentality caused the FFXIV team to take a lax approach to quality.

Fast-forward to the present day, where first-person shooter Call of Duty represents not only the ultimate evolution of FFVII's immersive narrative style – the entirety of any given Call of Duty campaign is basically a blockbuster movie in which the player advances the plot by shooting things – but also integrates leveling mechanics and permanent skill upgrades into its multiplayer component. Likewise the Uncharted games, the Tomb Raider reboot, the BioShock series, and nearly every other big-budget franchise of the past 10 years. Mass Effect 2 brilliantly combined the methods of the role-playing genre with the mechanics of a cover-based shooter. Countless games do what once made Final Fantasy so unique, but without the abstraction of menu-driven combat.

To stay ahead of the competition, Square Enix doubled down on presentation. Each Final Fantasy sequel has looked more visually splendid than the last, and the storylines have grown ever more arcane. But as the graphics improved, so too did the manpower required to create the art for the games. By Final Fantasy XII for PlayStation 2, art demands accounted for 70% of the game's development budget, and the leap to HD consoles only worsened the situation.

"On PS2, Square Enix focused on creating top-flight graphics. But resource requirements exploded in the PlayStation 3 era. Suddenly, there were too many craftsman." — Naoki Yoshida

Yoshida likens the artists working on FFXIV to craftsmen. Yet he conceded that the original game's misplaced emphasis on graphical quality was "probably a product of the company's success in the PlayStation 2 era.

"On PS2, Square Enix focused on creating top-flight graphics," he said. "But resource requirements exploded in the PlayStation 3 era. Suddenly, there were too many craftsman." Where once games could be engineered by small dozens of craftsmen, the move to HD meant that hundreds of artists were all working to create the best possible visuals – but within a structure designed for smaller teams. Collaboration gave way to individuals working at cross purposes. These craftsmen constructed one item at a time in isolation rather than moving in unison to develop a single cohesive whole.

Which brings us back to Lightning Returns, and Final Fantasy XIII, a game nearly as troubled as FFXIV.

Unlucky XIII

The deck was stacked against FFXIII from the very beginning.

"Final Fantasy XIII was originally slated to be a PlayStation 2 game," says director Motomu Toriyama. "However, our game development period coincided with the time when the next console generation was upon us and the announcement of the PlayStation 3/Xbox 360 was about to be made. So after working on the game for about a year or so, we had to make the decision of which console to develop the game for.

"It takes at least three years to develop a completely new Final Fantasy game, and our mission was to achieve the highest technology in game design. These two factors resulted in our decision to develop the game on the next-gen consoles instead."

Critical Miss: Final Fantasy XIII

2010, PlayStation 3/Xbox 360

Despite generally positive reviews and strong sales, FFXIII soured many people – fans and critics alike – to the Final Fantasy franchise. A victim of timing and a system ill-equipped to deal with the realities of HD game development, FFXIII spent years in development yet in the end came out feeling rushed, confusing, and limited in scope. Beautiful, yet incomplete.

In fairness, the blame for FFXIII's development confusion can't properly be laid at its creators' feet; had Final Fantasy XII not run well past its original ship date, FFXIII could quite likely have made it into the PlayStation 2's final days. Instead, a series of development complications delayed FFXII until 2006; it launched in the U.S. mere months before the PlayStation 3 arrived. By that point, PlayStation 2 was on its way out, and there seemed little chance that FFXIII could have sold well had it launched on the older system a year or two later. The team had to reinvent FFXIII from the ground up for a new platform.

As with FFXIV, the spectre of Final Fantasy VII played a part in FFXIII's difficulties. This time, though, the problem arose from a PlayStation 3 tech demo that recreated FFVII's iconic introductory sequence in real time to show off the power of the new console and the potential of Square Enix's next-gen White Engine.

"When we showcased the Final Fantasy VII Technical Demo on the PlayStation 3 at E3 in 2005, we realized its high potential," recalls Toriyama. "This directly spurred us to shift the game onto the next-gen console. It took us about six months to create the demo, and we pretty much had to put a hold on the development of FFXIII during that time."

Six months of development time for a 90-second, non-interactive video consisting of preexisting content? The tech demo presented an extraordinarily high standard of craftsmanship – impossibly high – to which the team felt compelled to target their new project. A year later, they returned to E3 with a fresh trailer, this time announcing FFXIII. That, too, promised a high standard of quality — one that unfortunately didn't truly represent the game as it was.

"The debut trailer shown at E3 in 2006 was created to depict the concept of Final Fantasy XIII," admits Toriyama. The E3 announcement trailer depicted the team's aspirations for FFXIII, but the game itself wasn't there yet.

"The debut trailer shown at E3 in 2006 was created to depict the concept of Final Fantasy XIII. Of course, as the trailer would be shown to a global audience, we worked to visualize what we would consider as our goal for a final game, instead of showing the early development stage of the game." — Motomu Toriyama

"The concept of Lightning as the female protagonist and the fast-paced ATB (Active Time Battle) system had already been decided by then. Of course, as the trailer would be shown to a global audience, we worked to visualize what we would consider as our goal for a final game, instead of showing the early development stage of the game.

"Elements relating to the lore and story that were created for the PlayStation 2 version of FFXIII were kept as-is, but we re-designed technical elements such as graphics, battle system, and game mechanics to specifically match the next-gen console specs."

The FFXIII announcement trailer excited fans with its promise of seamless integration between cutscenes and combat enhanced by a sleek, almost invisible menu system that created an illusion of real-time combat. But while Toriyama's group had already nailed down FFXIII's story, lore, and characters, the expression of those elements as a video game remained murky. By some accounts, the battle mechanics weren't fully locked down until six months before FFXIII launched in Japan.

Critical Miss: Final Fantasy XIV

2011, PC/PlayStation 3

Like FFXIII, FFXIV stumbled through development with the guiding philosophy that the things that had worked (or at least been tolerable) with FFXI would serve FFXIV as well. The end result was reviled by players and critics alike, a crushing disappointment of an MMO.

Then again, the team had plenty of time to sort things out while the White Engine – eventually reworked into the multiplatform Crystal Tools – took shape. "Naturally, we had to build a brand-new engine from scratch as the basis of the game, which was then tuned specifically for the next-gen console," says Toriyama. "Building the foundation of the engine alone took several years. During that time, the size of the development team was temporarily reduced, and we conducted basic technical research and produced preproduction assets before producing them on a larger scale."

"During the transition to the PlayStation 3 system, the technical know-how for character model sculpting and texture completely changed from that of the PlayStation 2. As a result, developers and artists were forced to adapt and change their existing knowledge and skills. We also needed to rebuild the workflow and development pipeline from scratch."

As a result of all this change in the face of the next-generation transition, the FFXIII project spent much of its time spinning its wheels. Despite launching nearly four years after its announcement in 2006 – by which time it had already been in development for roughly two years – Toriyama admits the final product was rushed through a short production timeline.

"Final Fantasy XIII was mainly criticized for its linear game design," he says. "There are several reasons for the game’s linearity. With a limited amount of development time and resources, we made the game linear in order to maximize the players’ gameplay experience and to provide the same type of gameplay experience to all players. By doing so, we aimed to offer the most entertaining gameplay experience.

"This approach had a great advantage in providing players with enough time to become familiarized with the new battle system and the unique world. But on the other hand, it led to players feeling like the majority of the game was a tutorial. I believe this was a big flaw in the game."

Fabula Nova Crystallis

After years of delays and complications, Final Fantasy XIII sold well – to date, it's moved nearly seven million units – but critical reception wasn't nearly so kind. It earned unusually mixed reviews, and forum discussions surrounding the game tended to be unkind. Many positive reviews took on a defensive tone, seemingly written more in response to fan conversations than about the game itself. Square had a hit, but going by online reception it felt like a miss.

The negativity surrounding the game left the future of FFXIII in doubt; in Square's grand vision, the game was to be the beginning of a whole new franchise within Final Fantasy. Perhaps emboldened by the success of its Compilation of Final Fantasy VII projects, Square Enix announced two companion games alongside the debut of FFXIII: A mobile card game Final Fantasy Agito XIII, and a stunning action RPG by Tetsuya Nomura's Kingdom Hearts team called Final Fantasy Versus XIII. The plan, obviously, was to plan ahead for a FFVII-level success and turn FFXIII into its own brand, called Fabula Nova Crystallis.

But the delays and complications that affected the game trickled down into its side stories. Agito and Versus ended up being rebranded as Final Fantasy Type 0 and Final Fantasy XV, respectively; the former moved to PlayStation Portable, while FFXV migrated from PlayStation 3 to PlayStation 4. Like Bravely Default, their new names were presented as an opportunity for the separate works to strike out and find their own identity. But the subtext many fans have inferred is that the name Final Fantasy XIII had become burdened with too many negative connotations – box office poison.

Critical Hit: Final Fantasy XIV: A Realm Reborn

2013, PC/PlayStation 3/PlayStation 4

Though it's called Final Fantasy XIV, A Realm Reborn is practically an entirely new game. New director Naoki Yoshida headed up what may well go down as the most extensive game patch in history, rebuilding FFXIV from top to bottom... and miraculously winning back countless disenfranchised fans in the process.

Nevertheless, FFXIII did spawn two sequels. Unlike the original Fabula Nova Crystallis plan, though, these took the form of direct FFXIII sequels that continued the original game's plot line. This had an obvious benefit: The sequels allowed the team to reuse existing assets (character models, settings, and presumably much of the extra FFXIII content that ended up on the cutting room floor) and recoup some of the costs of the first game's protracted development cycle. At the same time, Final Fantasy XIII-2 and Lighting Returns also offered the FFXIII team a chance to address the complaints that many fans had voiced about the first game.

"In Final Fantasy XIII, the battle system was reinvented, and we believe that generally speaking, the Paradigm Shift system was received well from the players who understood the system," Toriyama explains. "At that point, though, the best we could do in one game was to create a game where the players can master the basics of the battle. From there, I felt we could allow greater flexibility and increase the strategic element in the game. And so with Final Fantasy XIII-2, we decided to allow the evolution of the battle system by making the Paradigm Shift as the basis of the battle and having many monsters join your party as allies.

"The linear design of FFXIII had a great advantage in providing players with enough time to become familiarized with the new battle system and the unique world. But on the other hand, it led to players feeling like the majority of the game was a tutorial." — Motomu Toriyama

"On the other hand, the game design [in FFXIII] received many criticisms for its linear design. In order to allow for greater flexibility, we incorporated Historia Crux, a new gameplay and story element, which allowed players to freely travel between locations and visit them in different time periods as the crossroads of history."

In the end, the FFXIII "series" turned out to be a connected trilogy of fundamentally similar games by the same core team – quite a change from the original plan for a trio of almost completely unrelated titles by separate groups. In the end, it probably worked out just as well. Toriyama explains that the intent behind the different Fabula Nova Crystallis titles was to feature "various worlds using the crystal mythology as a framework." Yet the concept never really gelled with the public – in part because the deliberate ambiguity of the concept made it difficult to pin down.

Hit/Miss: Lightning Returns: Final Fantasy XIII

2014, PlayStation 3/Xbox 360

Though seemingly a sales flop, and the recipient of terribly mixed reviews, Lightning Returns was hardly the disaster many expected, and many who initially wrote it off have been won over by its forays into new, open-world territory for the series. If nothing else, it helped Square shore up its behind-the-scenes processes for the future – that is, for games that won't be dragged down by FFXIII fatigue.

"The Fabula Nova Crystallis mythology is not written like a detailed history book. While the content may be simple, like a fairy tale that gets passed on, it contains a vast world and mythology that are tied to various deities, making it too large to be told in one game.

"We realize that this approach may have been difficult for some players to understand in one game. The Fabula Nova Crystallis concept is so vast that it resulted in creating obscure settings of the world and a lack of explanation of the storyline. Moving forward, we’d like to make an effort to polish up the narrative and storytelling technique in order to create stories that players can easily take in."

It seems a tacit admission that the team put the cart before the horse in planning FFXIII as the fulcrum of a vast, sweeping mythos. In the end, Fabula Nova Crystallis turned out to have been much ado about nothing; both Type 0 and, by all appearances, Final Fantasy XV retain the original story elements that tie them to the Fabula Nova Crystallis. But given that those concepts – crystals and warring gods – have been part of Final Fantasy's DNA since the beginning, nothing about their plots specifically necessitates a connection to FFXIII or Fabula Nova Crystallis.

Righting the course

Despite the conspicuous improvements they offer, FFXIII's sequels haven't precisely scored home runs. While fans and critics alike generally agree they've both improved on the limited design of FFXIII, both games' aggregate review scores are considerably lower than that of their predecessor – and their sales have been even lower.

From a creative perspective, however, they seem to have met their developers' primary goal: Reinventing the broken process by which Final Fantasy games are made.

"We wanted to polish the development structure and respond to the mixed reviews that we received from the fans in the form of a sequel," explains Toriyama. "Final Fantasy XIII-2 was created after a new development method was put into place to thoroughly manage our milestones and to overcome difficult challenges we often faced during the development of Final Fantasy XIII. Thanks to that, the development process for both Final Fantasy XIII-2 and Lightning Returns: Final Fantasy XIII progressed smoothly."

In other words, FFXIII's sequels have played a similar role to A Realm Reborn: A chance for Square Enix's internal teams to reinvent themselves and come up with leaner, more efficient processes. In a sense, the games' ultimate sales are probably immaterial in the long run so long as they help prevent future entries in the series from falling afoul the troubles that undermined both FFXIII and FFXIV.

Toriyama says as much himself: "[For] Final Fantasy XIII, a large-scale team was starting the pre-production while the game engine was being developed at the same time. We relied on past experience, making estimations without clearly defining milestones, and not restricting the team structure with each development phase. It wouldn’t have been an issue if the game was an extension of a past project. But when there’s a major technological evolution or the game is developed for a console with completely new features, this method will not work.

"Because of this, we’ve been trying to improve our development process starting with Final Fantasy XIII-2. Since there are specific milestones, an appropriate structure and a specific number of staff needed for each development phase, we try not to force ourselves to proceed further in the process until we have clearly defined these milestones, team structure and have completed deliverables for each development phase. It may sound obvious, but this method is essential to ensure steady progression of the game development [process].

"We relied on past experience, making estimations without clearly defining milestones, and not restricting the team structure with each development phase. Because of this, we’ve been trying to improve our development process starting with Final Fantasy XIII-2." — Motomu Toriyama

"By the Final Fantasy XIII series becoming a trilogy, the Crystal Tools also evolved with each game. To give you an example of the technological evolution of the environmental design, with Final Fantasy XIII, developing a static image to match the PlayStation 3/Xbox 360 specs was the best we could do at that point. With Final Fantasy XIII-2, however, character lighting technology improved, in addition to incorporating a dynamic design, such as the weather and the game environment. With Lightning Returns: Final Fantasy XIII, we were able to deliver an even more dynamic world by incorporating the element of time.

"By evolving the game engine in each game, we were able to enhance the gameplay quality and our ability to be more expressive. It also shortened the development cycle."

FFXIII's sequels also represented another way in which Square Enix has been righting a listing ship: Collaborative outsourcing. Both FFXIII sequels were co-developed by tri-Ace, a studio that enjoys a lengthy history with the Enix side of Square Enix. While this delegated approach to production is standard practice among Western companies and a key to agile development processes, Square has traditionally preferred to handle major titles (especially Final Fantasy) internally.

Spanners in the works

Even if the new processes Square Enix has developed for Final Fantasy pay off, a number of question marks cast a shadow on the series' future. Both Yoshida and Toriyama have managed to salvage troubled projects and put a more relevant, contemporary spin on FFXIV and FFXIII. But this has come at the cost of the series' trademark visual quality; A Realm Reborn sacrificed granular detail for more impressionistic beauty, while Lightning Returns looks almost like a rough prototype compared to the graphically immaculate FFXIII.

Final Fantasy has sold in large part on aesthetic appeal since the beginning, where Yoshitaka Amano's gorgeous enemy designs set the games apart from other NES RPGs, but its most recent entries are far from competitive compared to the current works of studios like Naughty Dog, Kojima Productions, or Infinity Ward. It remains to be seen whether or not Square Enix can still incorporate stunning visuals into its games while working within the strictures of their new production methods. The company's new Luminous Engine certainly made for an impressive demo when it debuted at E3 2012, but regardless of the underlying tech, designing and creating such detailed graphics still requires significant manpower.

On the other hand, Final Fantasy XV looks absolutely stunning. Not only did last year's E3 trailer feature some of the most gorgeous graphics ever applied to a video game, it also showcased actual gameplay: Fast-paced, epic-scale, shooter-influenced gameplay.

Unfortunately, FFXV made its original debut almost eight years ago at E3 2006, alongside FFXIII (back when FFXV was called Versus XIII). Since then, it appears to have been mired in development hell, with Square Enix reissuing the original trailer with minor modifications each year and showing teasing glimpses of in-engine graphics. Even as recently as last year, FFXV leader Tetsuya Nomura pondered dramatic changes in the game's direction.

Of course, all these delays and uncertainties will be forgiven if the final product lives up to the standard of Final Fantasy's heyday. But regardless of the outcome, FFXV represents the sort of costly production boondoggle Square Enix wants so desperately to move away from. Whatever the quality of its final form – something we hope to have a clearer picture of after next months' E3 – FFXV feels like the last dinosaur wandering the frozen wastelands following an apocalyptic impact event.

????: Final Fantasy XV

TBD, PlayStation 4

And what of the next chapter of Final Fantasy? FFXV looks stunning, and it appears to take a radical approach with the series' mechanics. But will it justify the nearly 10 years' worth of work that will have gone into it by the time it launches? FFXV won't make or break Square Enix, but the reputation and direction of the Final Fantasy franchise hinge on its outcome.

There's also the bigger question, echoed in many of the questions Kitase has voiced, over what Final Fantasy should be. While the current trend of the mainline games is to move away from classic turn-based RPG play, that thinking left them flatfooted when the decidedly archaic Bravely Default became a legitimate hit thanks in large part to classic Final Fantasy fans hungry for a game that tickled their nostalgia. Dynamic action seems like the direction the games industry is heading for now, but does that make it the right direction for Final Fantasy? Or would a turn-based RPG for HD consoles be commercial suicide? Final Fantasy as a concept is big enough that there would seem to be room for both, but the series' direction points overwhelmingly toward frenetic blockbusters. A major factor in Bravely Default's name change came from the fact that the game's traditional stylings represent a take on Final Fantasy's past rather than a look at its future.

The saving grace

For Yoshida, it's essential that Final Fantasy's creators remember to keep their players in mind, to think like a fan.

"I don’t feel like my history with Final Fantasy is very different from people who’ve been playing the series," he says. "It’s been about 10 years since I joined Square Enix, but I’ve played the games since Final Fantasy I, just as a fan. It happened that I was able to be on the development team on a Final Fantasy title with ARR. As I was developing, I wanted to make a Final Fantasy that’s fun for me to play, because I’m a fan of the series as well. I’ve always felt that the franchise could use more fan service, so to speak – not to concentrate on a niche, but more to provide that fantasy.

"As you’re playing [A Realm Reborn], you get the sense that you’re playing through this as the hero of the game. I definitely wanted to emphasize that as one of the main elements, maybe more so than the other Final Fantasy games. With the hero resolving conflicts and accomplishing quests, it starts out in a small part of the world, and gradually expands to bigger tasks and a bigger range within the world. Finally, the hero will shoulder the burden of the whole world. A good blend of that element, and incorporating the Final Fantasy keywords that people would recognize, is how I bring in the essence of Final Fantasy.

"I was going for a sense like the bridge scene in the original Final Fantasy. When people play the game and feel that sense of nostalgia, to me that indicates that we’ve managed to successfully bring out Final Fantasy's essence." – Naoki Yoshida

"You explore and accomplish quests until about level 15, and then you earn the trust of the townspeople in each city. You get on the airship and fly out, and the theme music for Final Fantasy plays. When the team was looking at that part and testing it on their own, they felt, yes, this definitely brings out a sense of Final Fantasy. I was going for a sense like the bridge scene in the original Final Fantasy. There, the title doesn’t show up until you pass that bridge. With ARR, once you hit level 15, and you go on the airship with the expectations of the townspeople, that’s the beginning of your journey.

"When people play the game and feel that sense of nostalgia, to me that indicates that we’ve managed to successfully bring out Final Fantasy's essence."

Toriyama, on the other hand, takes a more pragmatic, technical view on his projects – and promises that generational challenges like those that affected FFXIII are a thing of the past.

"I believe that the Final Fantasy XIII series laid the necessary foundation towards the direction of next-gen RPG battle systems. This was done by adding the sense of speed and action-oriented approach to the fun, strategic aspect of the ATB system, a traditional battle system in the Final Fantasy series."

"While graphics are becoming more and more realistic, I believe that games that can enhance the appeal of the action-oriented gameplay with simple controls and rich playability will become increasingly important in the future.

"If I were to compare the differences between the previous console generation transition and the latest transition to the PlayStation 4/Xbox One, I would say that as long as the game is developed on a high-spec PC, it’s much easier today to make that technological transition. This is because with respect to the visual expression, shader-based technology is still used today."

As for Kitase, the man on a mission? He declined to discuss his as-yet-unannounced next project for the time being. Still, whatever that new venture turns out to be, it'll be interesting to see how much of the feedback he's been gathering from fans and press alike over the past few years makes it into the game – and whether or not his team manages to preserve the series' fundamental essence in the process.

Final Fantasy definitely has a difficult road ahead for it in the coming years. But realistically, there are few legacy franchises that began in the 8-bit era for which that's not true. Compared to most of its peers from the '80s, Final Fantasy still has a fighting chance to remain vital and relevant moving into the new console generation. The fact that its creative leads have made an active attempt to correct the series' course before it's too far gone gives cause for hope even amidst the uncertainty that has surrounded so many recent releases to bear the Final Fantasy name. And the warm reception that has greeted both Bravely Default and A Realm Reborn suggests that the series' estranged fans aren't so far away, eager to return when — and if — the series once again speaks to them.