When Nazis Ruled the Earth: The Tricky Politics of Wolfenstein: The New Order

How Bethesda and MachineGames handled the touchy task of letting the Nazis win WWII.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

Video game press events aren't what they used to be. The days of publishers reveling in bacchanalian excess to impress a handful of journalists are long gone, and good riddance. Lavish parties can't hide a mediocre product, and a great game speaks for itself.

The increasing scarcity of large-scale promotional events is precisely why I was surprised by the scale and spectacle of Bethesda's PAX East party in Boston this spring. It was precisely the kind of loud, lively event game publishers simply don't do anymore. Granted, it wasn't a press event per se — it was open to the public — though as a reporter I was allowed to sit in the VIP balcony area with the handful of game developers in attendance.

Sitting there above the crowded floor of fans writhing in time to '60s-style electric rock music, the surreality of the scene below struck me. The company had put the event together to promote the impending launch of Wolfenstein: The New Order, which was slated to arrive a few weeks after PAX. The New Order turned out to be far better than many seemed to expect — and it demonstrated a rare conviction of purpose by foregoing any multiplayer features whatsoever and existing entirely as a single-player first-person shooter.

No less daring, however, is The New Order's entire premise: Protagonist B.J. Blazkowicz doesn't single-handedly save the world from Nazi dominion. Here, World War II extended well beyond its natural lifespan thanks to Germany's use of advanced science and wizardry, and their enemies on both the eastern and western fronts slowly gave way to the Third Reich's unrelenting ferocity. The game begins in 1946, with the war still raging in Europe and the Nazis poised to perform a final coup de grace to cement their supremacy. Blazkowicz and his squad make a desperate foray into General Deathshead's fortress in Castle Wolfenstein... and fail.

Flash forward 14 years and the war is over. America's greatest cities are radioactive ruins. Nazis rule the world, replacing Europe's elegant historical buildings with brutalist structures, monuments to der Führer's greatness. It's dark, oppressive, hopeless, bleak — just the thing for a dystopian first-person shooter.

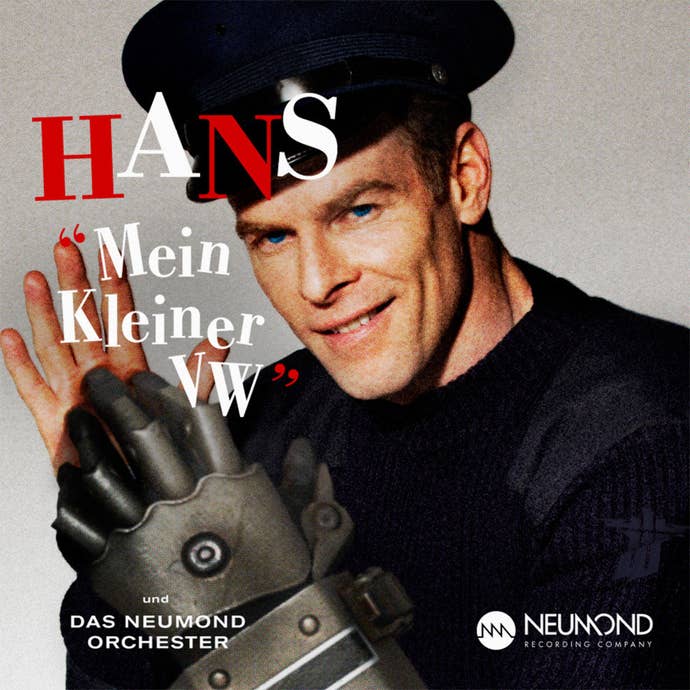

On the other hand, it makes for a weird PAX party. Bethesda decked the venue out to resemble a German dance hall circa 1960 — that is, the 1960 of The New Order's alternate timeline. An emcee dressed in a flamboyant Elton John-like getup strode onto the stage and conducted the entire event in German. Posters and other artwork plastered around the walls resembled a cross between Nazi propaganda posters and pre-psychedelic '60s artwork. The live band played music that sounded like Beatles-era rock with a more menacing edge.

The party reflected the underlying aesthetic concepts that defined The New Order — though of course Bethesda was far more circumspect with the live event than the video game. There were no swastikas to be seen at PAX, no actual propaganda, no mention of Nazis or world conquest whatsoever. Still, the underlying premise remained the same: What would the '60s have been like under a different world order?

"The 1960s in the world we live in was a time of cultural upheaval and anti-establishment humanism," says MachineGames' creative director Jen Matthies. "We asked ourselves how this iconic era would look if perverted through a Nazi filter. We wanted to explore the language of authority and oppression juxtaposed with imagery and concepts we’ve all come to associate with freedom and love. This cognitive dissonance runs deep through the game in everything from story to details in the environment.

"When designing the settings for the game, we drew a lot of inspiration from Brutalist architecture and the work of Nazi Germany’s chief architect Albert Speer. This combination, sprinkled with a little 1960s technological optimism, has yielded a signature personality to our environments."

MachineGames' efforts definitely paid off; The New Order is dense with detail and demonstrates meticulous research in the depth which which its Nazi-dominated world plays out. It makes for an unconventional setting, too. Most World War II fiction involves maintaining the proper order of history, fighting the Nazis' secret plans and bringing about V-E Day according to its ordained schedule no matter what kind of nasty plans Hitler secretly had in the works. Everything from Indiana Jones to the original Castle Wolfenstein held to this pattern. Even works that dabble in the idea of Nazi victory, such as Star Trek's "Mirror Universe" episodes, basically dress up the familiar with evil goatees before putting things right again.

The New Order goes well beyond these superficies, presenting its universe as a grey fascist regime where concentration camps have spread well beyond Poland and every major European skyline has been reshaped by massive constructs on the scale of the Volkshalle. And yet, at the edges of the story, you see signs that life goes on. Conversations overheard between citizens hint at the continuing desire to carry on with a normal existence despite the oppressive all-seeing eye of the secret police.

Perhaps more than any other factor besides environmental design, music factors heavily into MachineGames' world-building. The game's diegetic tunes — that is, the music you hear in-world rather than the accompanying score — play a key role in shaping Wolfenstein's alternate reality, flickering at the edge of the player's perception to create a sensation that feels at once familiar yet unsettlingly off. According to Mattheis, "Our approach to the diegetic music in the game was to explore how popular music would sound if it was forced to comply with a governmentally mandated aesthetic and drained of all creativity and soul."

Coincidentally, I spent most of the PAX East party talking to one of The New Order's composers. He corroborated Mattheis' comments, explaining that the bands referenced in-game are meant to be state-sponsored pastiches of real bands from the era, reflecting a twisted version of their real-world counterparts' attitudes. The Beatles and Rolling Stones send-ups, for example, were tasked with making the idea of obeying the regime and falling into line seem like the hip thing to do, playing off the impulse of teens to rebel against their parents and the underlying sense of discontent with the world's situation to foment compliance.

And, like me, he seemed struck by the unusual premise of the event and admitted that the game itself posed an interesting personal challenge for him, being of Polish and Jewish descent.

"I had a hard time explaining this project to my grandmother," he admitted, laughing. "She seemed very concerned — 'How can you work on a game about Nazis? You know, your grandfather fought against them...."

Hers was a fair concern, of course, one that I frequently wondered about myself in the run-up to Wolfenstein's launch. World War II isn't some abstract fantasy or distant historical relic; many people have been touched by its atrocities, either by living through them or simply by virtue of being close to someone who did. While WWII-based fiction is hardly uncommon, stories building on the premise of Nazi victory are. And building a game in such a world seems a task fraught with potential missteps.

Mattheis acknowledges the tricky tightrope involved in creating The New Order, especially given its inevitable release in Germany, where anything that could be viewed as glorifying Naziism is strictly verboten. "It's a criminal offense to supply video games with 'nazi symbols' in Germany, with all of the consequences related to that," he says.

"Movies like Der Untergang, Schindler's List, and Inglourious Basterds are excepted from this problem because they are considered as media art, contrary to computer games which are categorized as toys. And the jurisdiction looks at this issue very critically because using those unconstitutional symbols in toys could trivialize the atrocities of the regime."

So the question becomes not only how to create a convincing world ruled by the Third Reich, but also how to build it in such a way that overt Nazi references can be altered for the series' first-ever official German release without undermining the story's gravity.

"We’ve put a lot of work into this localization, and not only for the sake of legal safeguarding," Mattheis explains. "Wolfenstein: The New Order is not a typical FPS — MachineGames have packed an unbelievable number of details and background into the game in order to create an extremely dense atmosphere. And we’re absolutely certain that we have succeeded to transfer, intact, precisely these qualities into the German version. Alongside the aforementioned legal dimension, the depiction of violence in the game certainly pushes the limits of the local regulations as well, but we are extremely proud of the fact that we could stay true, particularly on this point, to our 'uncut' line over the past years. The graphic effects are also uncut in the local version."

The tricks Bethesda used for the German version of the game — for example, replacing historical Nazi emblems with the iconic Wolfenstein symbol — were the same ones they used for their PAX party. The posters that depicted the series' logo in stark white on a field of deep vermillion convey the concept of totalitarianism clearly enough, echoing the graphic design of Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union, but stop just shy of appearing as a celebration of the Third Reich. Even in the midst of an event crafted to mimic the game's alternate reality version of 1960, the point came through without being so blatant that attendees couldn't enjoy themselves. Just like real-world civil complicity with unjust governments, one might say.

The game also works in part because it inverts some clichés of war games while celebrating others. The New Order's story isn't perfect (our review refers to Blazkowicz's constant running narration as his "inner moronologue"), but it embraces the rules and standards of the genre while carrying them earnestly into new territory. For instance, the sadistic Frau Engel plays the part of the genetic tyrant on the nose, but her over-the-top performance makes for a memorable antagonist. The player's first encounter with her happens outside of combat; despite her being a slight, middle-aged woman — no match for Blazkowicz's powerful physicality — it becomes clear she holds the upper hand, to the point that she can terrorize a stranger twice her size simply for the sake of her own amusement (even to the visible discomfort of her lover).

"We work a lot with classic concepts we feel are absolutely integral to a true Wolfenstein experience," Mattheis says. "The lone army ranger against impossible odds is one of them. There are several classic war movie themes and characterizations we’ve chosen to incorporate and highlight in ways we haven’t seen before.

"B.J. Blazkowicz himself... our incarnation of him is based on the original Wolfenstein 3D version, where he’s this muscle bound action hero clearly inspired by the Stallone’s and Schwarzenegger’s of the late '80s/early '90s. Rather than shy away from this legacy, we’ve elected to honor it and go as deep with it as we can."

Even though Blazkovicz plays the Hollywood cliché of the big, tough, American hero out to save the day, he's not written from a typical American perspective. While publisher Bethesda is based near Washington D.C., MachineGames calls Sweden home. This gives them something of an outsiders' perspective on the topic of WWII; Sweden was one of the few European nations to remain completely neutral during the war, never invaded by Germany yet never allying themselves against the Axis, either.

"I think it’s been helpful when developing the story and characters to have a slight alien perspective," Mattheis agrees. "To write a good character, it’s incredibly useful to try and see the world from their point of view, even the most vile antagonists. This search for empathy and aspiration to see both sides of a conflict is deeply entrenched in the Swedish psyche."

"For all the over-the-top action and fiction that is at the core of this Wolfenstein game, we feel comfortable that we’ve treated the subject matter seriously and honestly," says Mattheis.

By and large, they succeeded. The New Order manages to pull off its unhappy premise of a world ruled by Nazis by making it clear the scenario isn't some perverse attempt at wish-fulfillment. The regime that rules the game's version of the '60s is never presented in a positive light; it systematically oppresses the public and murders dissenters. The government issues propaganda that contradicts the reality in which the player takes active part. The world under German rule makes impressive technological strides at a terrible price, including intrinsic flaws in the materiel fabricated for the purpose of rebuilding the world to Hitler's aesthetic preferences: The advanced concrete the Nazis have formulated proves susceptible to mold and, it's hinted, makes people ill from too much exposure. There are no nuanced enemies in this game, no subtle moral choices. You're not meant to sympathize with the bad guys — you're meant to take revenge on them.

There's nothing good about the world of Wolfenstein: The New Order... except maybe the cleverness with which that world has been created. Yet even the game's pop music, infectious as it may be, left me feeling uneasy as I left the game's PAX party. But it also made me more curious about the game — which was, no doubt, the point.