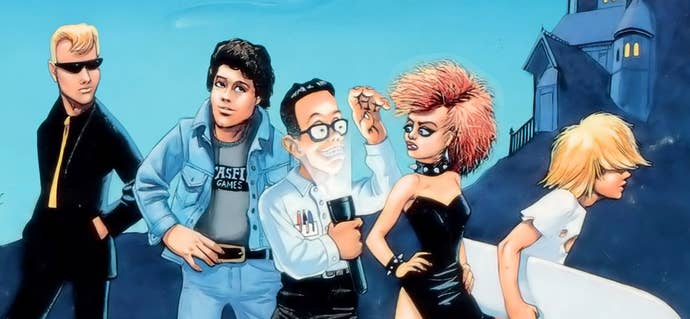

Use Questions on Developer: A Ron Gilbert Retrospective

Monkey Island creator Ron Gilbert reflects on 30 years in the industry, and a new chance to revive his old brand of point-and-click magic.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

King's Quest might have inspired Maniac Mansion's design, but, for Gilbert, this Sierra game was really just a jumping-off point. While his adventures would borrow the graphical interface of Lucas' competitor, Gilbert's games would be much different than Sierra's—they would be fair.

USgamer: We've talked about your "Why Adventure Games Suck" piece, at great length actually, and I’m just wondering: Did you feel that in the era of Maniac Mansion, making a game fair, or at least potentially "finishable" was considered innovative?

Ron Gilbert: Yeah, I think we were. I think it was a very conscious thing at the time, trying to make the adventure games so they didn’t have the dead ends to them, and I think we at Lucasfilm were trying to be different, too. Working for a company like Lucasfilm at the time, this was really in their heyday. Return of the Jedi had just come out and they were still making Indiana Jones movies, and I think we all felt like we needed to live up to that mystique of Lucasfilm. So we were trying to be different, we were trying to do things that felt like we were reaching a broader audience, that we weren’t just making games for nerds, that we were trying to make games for everybody else.

I think the lack of death and making sure the adventure games were finishable and fair, I think that was just a part of that, a part of that philosophy we were trying to do. You know, I’d done—I don’t remember which GDC it was—but back then I had done a little one-on-one debate with a designer from Sierra about why death in adventure games was good, and they were taking the attitude of why death in adventure games was good and me saying it was bad, and so it was something that warranted an entire GDC talk.

USg: So, as one of seven employees at the beginning of Lucasfilm Games, did it seem at all possible that you would one day be directing your own projects? Was it that open of an atmosphere, in terms of collaborating and pitching ideas?

RG: It wasn’t initially. When I came on and got the job, I was just a contractor, I wasn’t even an employee at the time, and I didn’t know anything about the Lucasfilm Games group—I didn’t even know that Lucasfilm made games. When they called me up and they wanted to know whether I was interested, I was kind of floored. Lucasfilm was Star Wars and Indiana Jones to me, not games at all, so I didn’t really have a lot of preconceived notions; I was just overjoyed and thrilled to be working there. But quickly, within a few months of working there, it was pretty clear that this was a very collaborative group of people, and they didn’t have these segregated tiers of “Well, these people are game designers and these people are programmers and these people are artists.” I think everybody was a game designer, and that’s something that was instilled in everybody there at some level, so I think it was pretty quick that I realized I can probably do more than just port stuff over.

USg: In terms of technology, what were the most exciting advancements that happened when you were at Lucasfilm Games/LucasArts?

RG: Well, I think there were probably three things that were exciting to me. One was the graphics, when we moved from EGA to VGA graphics; having 256 colors instead of 16 colors was actually a major leap forward for stuff. As amazing as [Monkey Island background artist] Mark Ferrari’s art was in EGA 16-bit stuff, [once you] move to 256 colors, it feels like a game-changer in a lot of ways. You could put images on the screen that stop looking like video game graphics and actually look like something they’re supposed to be, and so that was very exciting. That was a very exciting leap forward.

The other thing was just with storage, when CD-ROMs came around and suddenly we didn’t have to worry about storage any more. I remember on Maniac and Monkey Island and all those games, throughout the entire project there was always this stress level of “are we going to fit on five discs?” Because we had been given a budget by the company that says “this thing has to fit on five discs” or six discs, or whatever it was, because that’s what they had priced out the cost of the box to be. So there was just always this thing in the back of your head was like “can we keep this scene? Can we keep this animation?” just because it might go on to a sixth disc, and we can’t do that. With the advent of CD-ROM, that kind of went away; it went away for a while, it cropped its ugly head up again eventually, but there was just this plate where it was “well, we have so much space now, we no longer have to be limited by anything creative we wanted to do by the storage medium,” and I think that was a huge leap.

Then I think the next thing that was kind of a game changer was digital audio, when we’d actually play back digital sounds and especially voice—that was a big thing.