TurboGrafx-16 at 25: Remembering the Little PC Engine That Could

In August 1989, NEC launched the TurboGrafx-16 in America. We explore why it lost the console wars — and why it was great nevertheless.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

When old gamers wax rhapsodic about the 16-bit console wars, they're really talking about the conflict between Nintendo's Super NES and the Sega Genesis. Case in point: Blake J. Harris' recent book by the same name, which extrapolates semi-fictionalized conversations from the real history of the early '90s. It's all about Sega and Nintendo going to head-to-head, frequently with a bloodthirsty nastiness that belies the whimsical, kid-friendly nature of the merchandise being peddled.

If Hudson and NEC's TurboGrafx-16 enters these console war conversations at all, it's strictly to serve as a footnote or distraction. And fair enough, one might say; despite having had the number "16" appended to the end of its name, the TurboGrafx was more of a bridge between the 8- and 16-bit generations, with an 8-bit heart boosted by 16-bit video components. This amounts to splitting hairs, though. In any case, the TurboGrafx more than held its own against other 16-bit consoles in Japan.

While Sega proved to be Nintendo's greatest nemesis in the U.S., the Genesis (called the Mega Drive in Japan) amounted to nothing more than a distant also-ran in their home market. In Japan, the TurboGrafx-16 (known as the PC Engine over there) didn't put as big a dent in Nintendo's mindshare as Sega did over in America, but the system certainly built a significant following. Sega ultimately sold roughly 40 million Genesis consoles around the world, but less than a tenth of those were to Japanese customers. Meanwhile, the PC Engine moved merely 10 million units during its lifetime — but roughly eight million of those sales happened in Japan, making the system twice as popular as Sega's Mega Drive and nearly half as successful as Nintendo's mighty Super Famicom.

Clearly the machine had legs, but NEC and Hudson couldn't translate its domestic popularity to the overseas markets; the system never even saw an official release in Europe. Despite being a major player at the console wars' point of origin, the TurboGrafx-16 barely registered a blip in the global battlefield.

House of the Rising Sun

"While the big three — Nintendo, Sega, and NEC — were obviously based in Japan, that wasn't always apparent in the 8 and 16-bit days," explains Tomm Hulett, a director at WayForward Technologies. "Nintendo made every effort to appeal to everyone as the industry's Disney equivalent. Sega was very busy coming across as cool and hip to American MTV kids. The TurboGrafx may have followed Sega's lead as far as marketing was concerned, but the games made no such effort. They arrived without much alteration, fully Japanese and a little weird to [American] kids like me. It made them feel exotic, and a little removed from the common fare Nintendo and SEGA were serving up."

As two of the world's most active and prolific regions for game development, America and Japan have always shared an uncomfortable relationship. People in both countries love video games, and they're good at making games, but what plays in Peoria rarely goes over in Osaka. Case in point: Atari's profound failure to make a dent in Asia back when the Atari 2600 was essentially the only game in town.

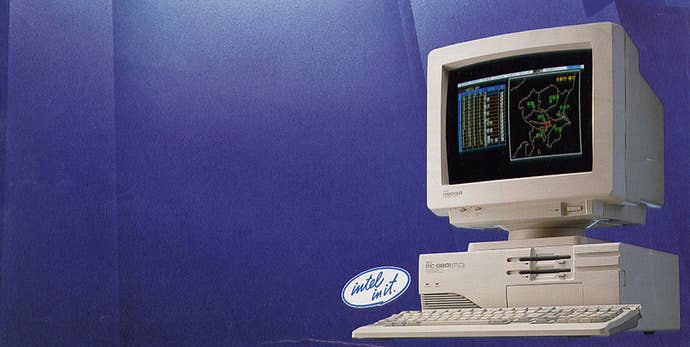

Nintendo and Sega succeeded in the West in large part because their games either eschewed cultural specificity (as in Nintendo's case) or else actively embraced the foreign market (a major key to Sega's Western popularity). The TurboGrafx, however, was a profoundly Japanese device. And little surprise; its innards came from NEC, the company that essentially owned the Japanese PC market in the '80s. Where Americans gravitated toward DOS-based IBM clones or Apple II and Europe preferred Commodore 64 along with locally grown microcomputers, Japan collectively settled on NEC's PC-8801 and PC-9801 family. It helped that those computers, unlike Western-developed PCs, offered high-resolution graphics capable of displaying complex Japanese-language character sets.

Countless Japanese developers cut their teeth on the 8801, and the system's extremely local focus meant — unlike Nintendo and Sega games designed for a global audience — the software that appeared on PC-8801 could drill down into the preferences and peculiarities of the Japanese marketcandle. The 8801's library makes for a fascinating study in an alternate history of video games that Americans never experienced, but to those not versed in Japanese culture and tastes, those obscure games feel more like an anthropological study than a chance to discover inviting rarities.

NEC's foothold in the PC space gave the TurboGrafx a built-in audience; it's no coincidence that the system went by the name "PC Engine" in its home territory. NEC and Hudson hoped to send developers and gamers alike a message: Want in on console mania but find the aging Famicom too cramped, too limited, too simplistic? Here's a system that's more like our computers. It's powerful. Sophisticated. Capable. And their targets took the bait; the PC Engine sold a couple million units in its first 18 months of existence, marking it as an unequivocal success — especially considering how poorly previous prospective Famicom competitors had fared in the face of Nintendo's juggernaut.

TG16 enthusiast Matthew Flott has noticed the system's computing heritage throughout his own experiences. "Looking back on it, I think I felt a lot of similarity between PC games and TurboGrafx games," he muses. "Most of the games released on the system were focused on single-person play, and text-heavy in many instances. They seemed to have the darker tones of media aimed at adults, which was different than Sega and Nintendo's games-as-toys approach. I mean, hell, there was only one controller port!"

But the underlying aesthetics and sensibility of PC-8801 game design carried over to the PC Engine. It looked, unquestionably, every bit the part of a machine made for a Japanese audience: A diminutive little square of plastic barely larger than the controller that plugged into it, playing games on tiny credit card-sized wafers. It was a far cry from the chunky machines and bulky cartridges that Americans gravitated toward, and the software that beamed out of the console seemed equally exotic. Hulett cites the TurboGrafx as "the first time it really struck me that these awesome video game things I was playing actually came from a completely different country.

"I knew logically that everything after my Atari came from the far-off land of Japan. I even knew they ate sushi there. But it never really struck me just how foreign the place might be until playing Keith Courage in Alpha Zones. Reality hit me in the face, hard. What a weird game, filled with things I'd never seen before."

"TG16 games tend to be bright, colorful and 'clean,' if you will," says Kevin Bunch, currently the world record holder for the TG16 version of Splatterhouse. "There's not a lot of potentially muddied detail that just detracts from the image. Compare Devil's Crush to Dragon's Fury on Genesis."

Overseas, overwhelmed

The PC Engine library banked in part on being different — on its quirkiness. Where else would you find a shooter called Toilet Kids in which you fight your way through a colorful world composed largely of cartoon feces and other bathroom references? What other system would give birth to J.J. and Jeff, which in its original form was based on a comedy duo with a penchant for, yes, potty humor? Or Bonk's Adventure, in which you control a not-particularly-cute platformer mascot with a massive cranium and a generally irritable attitude? Or the sole home port of Wonder Momo, Namco's strange arcade game in which you battle through what appears to be a stage production of a magical girl show while the audience tries to get a peek at the heroine's underwear? Or Gekisha Boy, a bizarre precursor to Pokémon Snap in which you help an aspiring photographer snap pictures of utterly outlandish scenarios?

Which isn't to say the system only offered weirdness. On the contrary, it made its mark in large part by offering crisp conversions of current arcade hits, something its 8-bit competition couldn't even begin to do.

"I really think the arcade-oriented library of the system really makes it unique for the time period," says Bunch. "The NES was definitely not focused on those burst, pick-up-and-play for 10-20 minutes type of games, nor are the Genesis or SNES libraries for the most part. TG16 has the shooters, arcade ports like Splatterhouse and Cadash, arcade-ish games like Parasol Stars and the Crush pinball titles... sure, if you're good, you can last a while, but the console never struck me as the home of the mascot platformer like its counterparts ended up being. Even things like Bonk or Keith Courage are definitely not the norm for the console library, to me."

For shooter fans — that is, bullet-frenzied spaceship shoot-em-ups, not the first-person variety — the PC Engine and TurboGrafx (as well as the system's eventual CD-ROM add-on, the Duo) represented a slice of heaven. Hudson led the charge with its own Star Solider family of games that spun off from Tecmo's Star Force. The mid-generational technology of the TurboGrafx made it ideally suited for shooting action — the hardware had the power to push lots of sprites, but at the same time it didn't have the ability to render quite as much color and detail as the Genesis and Super NES, which made for a cleaner look — a godsend for fast-paced shooters crammed with countless fast-moving objects. The system has become something of a legend to shooter fans, and rare or Japan-only releases like Sapphire and Magical Chase command impossibly high prices.

Yet this focus on blazing action and surreal quirkiness proved to be a sort of overspecialization when it came time for the PC Engine to launch in America as the TurboGrafx-16 in the summer of 1989, two years after the system's Japanese debut. American gamers tend to gravitate more toward realism, character-driven action, and sports: Areas that PC Engine developers had been slow to build in. Despite the console boasting a healthy library of releases in its home market, when it came time to focus on the West, NEC America found itself in desperate need of viable releases, and that showed from the very beginning.

"The bundled game we got, Keith Courage in Alpha Zones, might be the worst pack-in game in history," says TG16 enthusiast Marshall Martin. "At least, it was the worst until that point. Much too 'Japanese' for a seven-year-old to appreciate. It seems like the best games weren't localized, too. NEC probably gave up on the U.S. after what I'm assuming was a really weak launch."

Much as would happen several years later with Sega's Saturn, the TurboGrafx's sluggish start had a cascading effect on the console's fortunes: NEC America circled its proverbial wagons by leaving excellent but "foreign" releases in Japan and focusing on a narrow selection of localized games that it deemed suitable for the U.S. The disparity in releases between regions, already pronounced thanks to the system's two-year lead in Japan, grew worse as time went by. TurboGrafx-16 managed to wrangle up a couple million fans in America, but today most enthusiasts focus heavily on imports.

In a lot of ways, the late American release of the system probably sealed its fate. The PC Engine launched in Japan a year before Sega debuted the Mega Drive, but here the Genesis actually beat TurboGrafx-16 to store shelves by a matter of weeks. Technologically speaking, NEC's console didn't hold a candle to Sega's — but that didn't matter so much in its home territory, where its only competition for the first year of its life came from Nintendo's aging Famicom. Its early lead over Sega quite likely accounts for the ultimate triumph of the PC Engine over the Mega Drive.

That same first-strike advantage fell to Sega in the West, however. Genesis launched with superior graphics and a visually stunning conversion of arcade brawler Altered Beast in tow — perhaps not the greatest game ever made, but more visually impressive and a lot more U.S.-friendly with its manly monster-punching action than the bizarre Keith Courage. Right out of the gate, Sega had the upper hand. Within a year of the Genesis launch, Sega had a line of top-flight American sports games locked down. A year after that, Sonic the Hedgehog launched and made a campaign of turning Mario into a laughingstock; after that, the race between Super NES and Genesis ran neck-and-neck, with TurboGrafx a distant third. The system's own de factor platformer mascot, Bonk, didn't even rate a mention in Sonic's campaign.

As the TurboGrafx's chances receded, NEC America handed over the reins to a newly established company called Turbo Technologies, Inc. TTi made a noble effort to rejuvenate the system's image in the U.S., embracing the same aggressive marketing tactics as Sega, though with mixed results. The outlandish comic book-style Johnny Turbo campaign has become an ironic Internet favorite, as popular for its over-the-top attacks at the system's rivals ("They're not even human!") as for the bizarre fact that the character was based on an actual TTi employee, and in some ways the ads appeared more interested in mocking him than selling systems. A more successful gambit came with the inclusion of discount coupons alongside the Turbo CD peripheral that helped soften the blow of that add-on's steep price.

Still, try as they might, TTi couldn't change the physics of market inertia. The competition gained steam as the Turbo family slowed down; even the release of the spectacular TurboExpress — a full-color portable system capable of playing the same HuCard games as the full console, absolutely spanking both the Game Boy and the Lynx in terms of power — couldn't sell America on the merits of the machine.

The TurboGrafx-16 Legacy

"TG16 was just another console whose prowess in amazing 2D games would've blown the NES out of the water," says TG16 fan Kenneth Wesley. "But by the time it launched, Genesis and SNES felt like the future. It became a niche console for niche gamers. It has a solid lineup though, which was more than I can say for the Sega CD. Had the TurboGrafx attracted the right backers and publishers, the early '90s gaming landscape could have been altered dramatically."

TurboGrafx-16 may have arrived in America too late to get a competitive edge in the 16-bit market, but in truth it's hard to imagine a scenario in which it could have done any better. The console arrived in Japan late in 1987; had it been localized for America a year later, as was standard for Japanese consoles until PlayStation 2, it would have arrived here right as NES mania reached its fever peak. The American market was still in recovery mode following the Atari crash, and Nintendo had ample momentum. And by that point, NES games were beginning to incorporate much more sophisticated add-on chips, making the TurboGrafx-16 seem like a half-step between generations.

"I just don't think there's room in the industry for 3 equally successful parties," says Hulett. "Gamers go where the exclusives are, and TG16's offerings just weren't as meaty as their competition. It would be interesting to see an alternate world where Bonk's Adventure or J.J. & Jeff had the same quality as a Mario or Zelda, and NEC continued to thrive off exclusives alone like some proto-Gamecube."

"The easy answer is that NEC should have brought out a lot more games — good ones — from the Japanese market than they did," says Bunch. "But with the chokehold Nintendo had the market in the late '80s, I'm not entirely sure NEC could have made much more headway than they did. Perhaps if NEC had catered to third parties and had a Sonic-level killer app like Sega did, they could have at least gotten the breathing room to change their strategy."

Even though it offered a remarkably diverse lineup by the end of 1989, ranging from brawlers to shooters to strategy games, the TurboGrafx library simply didn't connect with American gamers the way Nintendo and Sega's games did. NEC leaned heavily on Japanese-developed games from Hudson and partners like Namco and Atlus; fewer than 20 of TurboGrafx-16's official U.S. releases came from Western studios. The U.S. TurboGrafx-16 HuCard library never even made it to 100 releases, whereas Japanese fans saw more than 300.

The numbers look even grimmer when you factor in CD-based games, of which less than 50 official releases came to America. Japanese consumers, however, had more than 400 CD releases to choose among. In that light, the U.S. market's failure to adopt the Turbo CD ultimately proved to be the greatest limiting factor for the system's viability. Official CD-ROM releases continued to appear in Japan until 1997, well after the advent of the succeeding generation of consoles; as of 1993, however, the platform was effectively dead in the U.S. The one game to see U.S. publication in 1994, Dynastic Hero, was produced in such small numbers that it now commands prices upwards of $1000.

Time has been kinder to the TurboGrafx-16 than gamers of the '90s were, though. Thanks to their sharp visuals and no-nonsense play appeal, the system's better games remain entertaining to this day. And while America found itself on the short end of the CD software stick, the lack of region-locks in the Turbo CD and PC Engine CD-ROM

JJ & Jeff vs Kato & Ken

One of the most popular first wave PC Engine releases was Kato & Ken, a rather lavatorial platformer starring the hosts of Japan's equivalent of America's Funniest Home Videos. While its gameplay is solid and entertaining, more memorable are the crude antics of its starring characters. Laying deuces behind hedges? Check. Squatting and launching deadly puffs of flatulence from the rear? Why not. Tinkles being taken up lamp posts? You got it. Birds dropping bumper-sized cleveland steamers? Oh yes. Big bonuses for kicking your partner in the nates? Of course.

The game was released in the US under the name of JJ & Jeff, sans rudeness. Tinkles were still taken, but there was no visible stream - just the character bobbing up and down in a way that left much to the imagination. A mask was used to cover the red, straining face of the person dropping an otter behind a bush, which made no sense in the general scheme of things. The least incongruous change was swapping out the original's rearward-firing, naturally produced, airborne toxic cloud for a forward-firing one that emitted from a spray can.

JJ & Jeff is a curious footnote in TG-16's history, but one thing it does do is highlight just how utterly strange and arbitrary corporate decision-making can sometimes be. Two things were kept from the original game: beautifully curled turds continued to rain down from the heavens, and kicking your partner's ass was A-okay. At which meeting were these solutions brainstormed and decisions made? And who made them? It would have likely been quite entertaining to have been a fly on the wall.

"In the U.S., the Turbo has developed a sort of mystique, much like the Saturn," says Bunch. "It has a solid library of arcade-style games, several of which are looked at as some of the best games of their era... though collectors tend to snap up anything that isn't nailed down for the system, so it can be expensive to get physical copies of the good stuff.

"And, much like the Saturn again, there's still kind of a mystique over the stuff that is not readily accessible via Virtual Console, PSN, or Xbox Live. So in a sense, I feel like the strongest image the Turbo has in the States has nothing to do with the machine itself, but just the idea of it. Unless you're a shooter fan, in which case you probably worship the table the TurboGrafx sits on. And given how it barely touched the European market, that mystique is probably even greater there.

"While I can't necessarily speak for Japan, it seems to me as an outsider that the system was the first proof of just what companies could do with the CD format at much lower cost than cartridges (or cards, as the case may be). Obviously that's a huge deal, and as the system did much better over there it seems like it became the home of the sort of more bizarre Japanese design aesthetics that we didn't see much of until the PS1 era (again, Wonder Momo, dating sims, and Mr. Heli all spring to mind). I think you could also make the case it had the best home ports of Neo Geo fighters outside of the Neo itself for quite a while, which certainly doesn't hurt its arcade gaming credentials."

For the millions of seasoned gamers who spent the '90s embroiled in the Sega-Nintendo console wars and pining to relive the sense of discovery of bygone days, TurboGrafx-16 represents a potential hotbed of "new" games just waiting to be found. Although the scarcity and Japan-exclusive nature of many of the system's best releases (such as the legendary Castlevania spin-off Dracula X: Rondo of Blood) can make for a pricey hobby, NEC's excellent console simply begs exploration.

As the TurboGrafx-16 turns 25 this month, why not take this occasion to discover (or even rediscover) the greatest console that never quite caught on in America? We recommend you start with the following American releases, and once those whet your appetite, move along to the more esoteric pleasures of the PC Engine and its CD library. Just be prepared to pay for the privilege.