True Tales from Localization Hell

COVER STORY: Three veterans of video game translation recount their most harrowing projects.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

"Traduttore, traditore." This 19th century adage meaning "translator, traitor" proves anxieties over moving a work from one language to another haven't recently sprung into existence. (Appropriately enough, this proverb works as a pun in its original language, but not so much in English.)

In short, translation is an imperfect art. Transforming words from one language to another stands as its own challenge, but capturing the essence of meaning—often tied to specific beliefs and experiences—is another obstacle altogether. And when you're dealing with cultures as different as those found in American and Japan, nuance isn't just helpful; it's absolutely necessary.

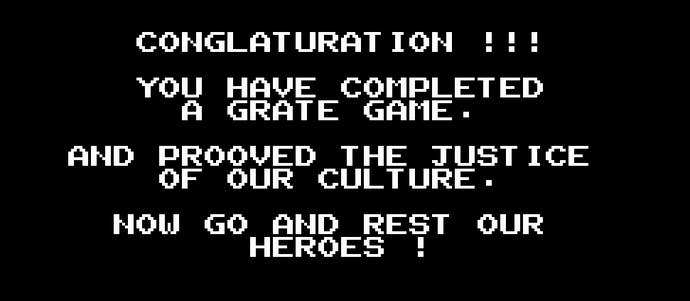

While it's true video game localization (if you could even call it that) didn't rise far above "congraturations" in its earliest years, in the passing decades, it's transformed from an afterthought to a legitimate career path. Throughout the '90s and early '00s, talented localizers raised the bar for dialogue and voice acting in Japanese video games brought to the States, causing the industry as a whole to follow suit for fear of appearing stuck in the awkward past.

What follows is a discussion with three video game localization editors who paid their dues in the localization mines with some very notable—and beloved—projects. For the sake of revealing the intricacies of the process, this cover story will focus on their most difficult projects; the ones that, through technical issues, cultural barriers, or other problems, gave them their greatest challenges.

Alexander O. Smith

The PlayStation era saw developer Square at the height of of both success and prolificity. After building a strong reputation in America over the 8 and 16-bit years, Square launched Final Fantasy VII, whose impressive graphics and epic, three-disc adventure helped bring scores of reluctant Americans into their RPG fold. During this period of newfound relevance, a localization editor named Alexander O. Smith began working for the company shortly after getting his Master's in Classical Japanese Literature from Harvard.

Though Smith began his career at Square with 1999's Final Fantasy VIII, it would be a year later before one of their RPGs bore his distinctive voice. 2000's Vagrant Story was the first game by the developer to carry Smith's distinctive Shakespearean stamp, which he would later apply to other RPGs like Final Fantasy XII and Tactics Ogre: Let Us Cling Together. With an impressive amount of credits under his belt at Square, Smith's most taxing project would take the form of Final Fantasy X, which stood as the first time the developer embraced voice acting in their long-running series. Figuring out the best way to implement this new element, though, would be quite the learning process.

USgamer: Can you talk about the complications involved in working with voice acting for the first time?

Alexander O. Smith: Well, nobody really knew what they were doing, even on the Japanese side, and that led to one key miscommunication in the lead-up to the project. And, the miscommunication that happened was [voice director] Jack [Fletcher] had asked several months before the project began whether there was going to be ADR recording—to lip flaps, basically. And he was told by somebody—not at Square Japan but at Square Hawaii—who had been working as a go-between, that there would not be syncing to lips. And, the video that he had received at that point, a few months before we actually began recording, was indeed rough cut and didn’t have lip-flaps, or where it did they were garbage flaps that had nothing to do what was being said—the mouths were just moving randomly.

Essentially, it came down to having to rewrite the script to fit not just the lips, but also very, very strict length considerations. We had been aware of that when we were working on the original translation, but we didn’t realize how serious they were about not having the English voices go over the length of the Japanese voices at any point. Because the way that the game engine was triggering sound files was tied into the same system that it was using to trigger action on the screen, so if you had a sound file that went overboard by even half a second, it could throw off the entire scene and you could get a crash.

[W]hen it became clear that a lot of the script had been written roughly to length, but nowhere near as tightly to length as it needed to be... you’ve got to have a line in 2.3 seconds, you can’t write a three-second line for that, or a 3.5-second line. It has to be a two-second line. And it makes a really big difference, and when you get to five seconds and six seconds, you can start compressing the files a little bit and tweak the length without making it sound too strange. So, there’s a lot of rewriting for that, and of course, all of the well-articulated lip scenes, which were many in Final Fantasy X, had to be completely rewritten so the lines fit the lips.

USg: I do remember that the US release of Final Fantasy X was supposed to be 2002, but it came out around Christmas of 2001. I’m not sure if that was something that was always in the works, or if that was something sprung on you.

AS: Yes, we had a really leisurely schedule, and then it got moved up by about three months. That was a marketing consideration. It had nothing to do with the progress of the translation or the game or anything. It was some sort of—they wanted to get it out before Christmas kind of thing. And, yes, now that you mention it, we did get things moved up. That sort of thing happens in general with a lot of games, you can get things moved up on you.

USg: So, where did the biggest difficulties come in? Obviously, you’re telling me this is everyone’s first time with voice acting, and from that point on almost all Square RPGs would have voice acting.

AS: Yeah, it was a real grind for me, personally, because the rewriting every night after a full day in the studio. Something had to give there, basically, so, in that case it was just me. I ended up putting in ridiculously long days for two months, basically, to get that out the door.

It was not made clear to us how precisely we had to match the Japanese timing. Or, if it was made clear to us, we didn’t really understand. We didn’t take it seriously enough. [There] wasn’t terribly good communication between the sound department and localization at the time, and so, nobody really sat down and said, “Look, these files have to be exactly this length.” And even if they had, since we’d never recorded anything, I’m not sure whether that would have meant the same thing to us before recording as it did during recording.

[With] a ten-frame [line of dialogue], you can’t even say "yes" in ten frames. It’s thirty frames a second, so ten frames is a third of a second, and you can’t say the English word "yes." You can say the Japanese word hai in twelve frames, but you can’t say "yes" in twelve frames, because the "s" sound drags out. No matter what you do, you end up around 25 frames or something. So, even at that level, it was challenging, because I was having to make a lot of decisions that I think affected the final quality of the game for reasons that had nothing to do with the scene or the writing or the emotion of the scene, it was all about technical difficulty. And, given maybe twice the amount of time, maybe I could have found my way through that a little better.

It’s an entirely different skill set from translation, because you’re rewriting to very, very unusual constraints. "I have to end this line with a vowel sound." That kind of constraint. It’s a bit like poetry, or trying to write a haiku, because you have X number of syllables, and in the middle you’ve got to have some really rapid lip flaps, and in the end, you’ve got to end with an open mouth. And so, just learning all that and how to write those scripts and how to write lines that end in a vowel and don’t end with "You know" every time, because that’s an easy one. I think Rikku got her little, "You know—" she ends a lot of lines with "You know." And that was just sort of a, "Well, we’ve got to do something, and that can just be her thing, a vocal tic for her."