Too Powerful for Its Own Good, Atari's Lynx Remains a Favorite 25 Years Later

Though it never stood a chance against Game Boy, America's first major portable system worked its way into many hearts.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

The console war mentality has dominated gaming culture ever since George Plimpton first espoused the superiority of Mattel's Intellivision over Atari's 2600. Given the combative nature of so many video games — the medium got its start with head-to-head competitive experiences — this sort of us-versus-them narrative more or less writes itself.

From this comes the idea of winners and losers in the business of creating games. Which hardware was better? Which had cooler games? Who sold more? History texts favor the winners, and everyone else becomes relegated to also-ran status.

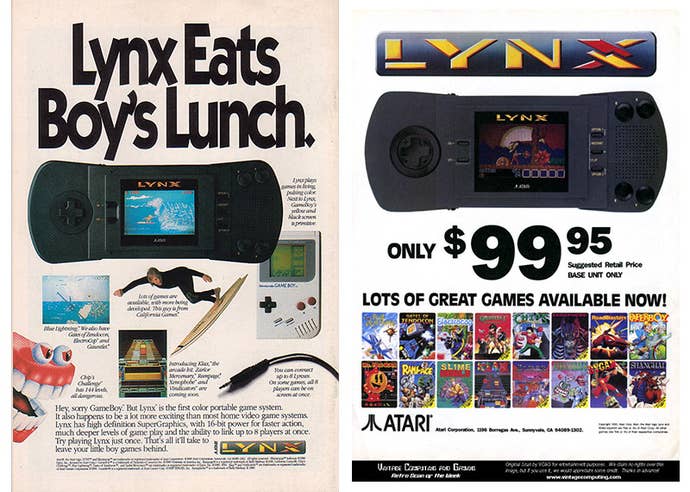

Consider the Atari Lynx, which launched in direct competition with Nintendo's Game Boy. No one had produced a serious portable game console until summer 1989, when suddenly two systems entered the market in rapid succession. Game Boy beat Lynx to stores by a matter of months, but that small jump was enough of a lead to cement its triumph over Atari's console.

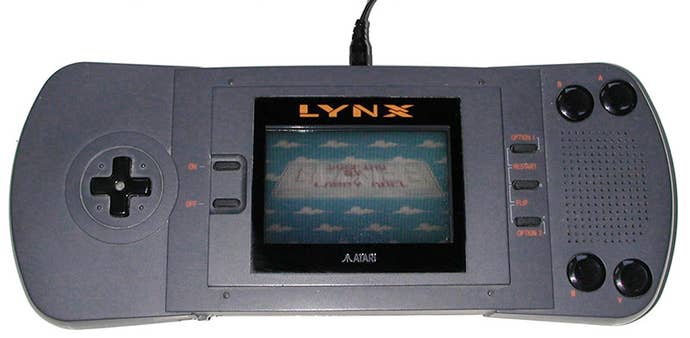

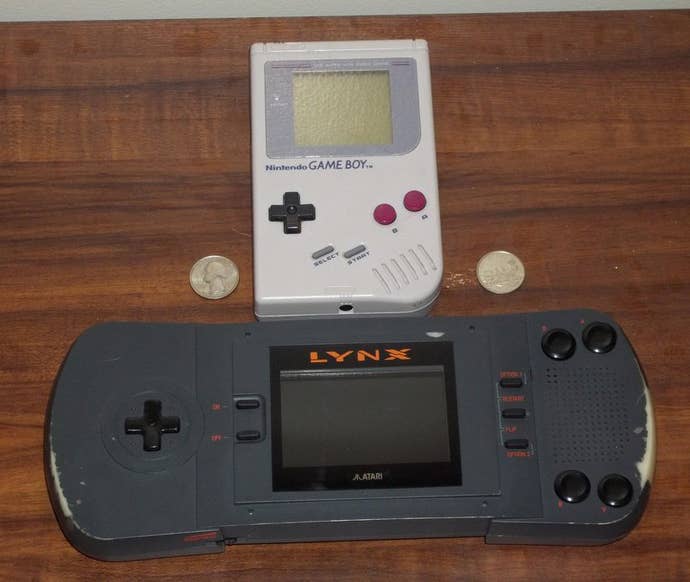

Yet by all appearances, Atari's system should have won the first portable console wars. It was a beast of a machine: Powerful, versatile, gorgeous. Where Game Boy could output smeary greyscale sprites on a tiny screen, Lynx could churn out incredible scaling sprites in full color on an LCD nearly twice the size of Game Boy's postage stamp screen. Anything Game Boy could do, Lynx could do better. Graphics? Not even close; Atari churned out intense arcade games in miniature, whereas Game Boy was better suited for static puzzle games. Networking? Game Boy's Link Cable could theoretically connect 16 systems; Lynx's ComLynx could, too. Playability? The chunky Lynx was comfortable to hold, and its ambidextrous controller design hearkened back to the inclusivity of old arcade games, whereas Game Boy was simply an NES controller with a screen built in.

And yet, in the end, Lynx experienced a rocky existence, fading from the market after five dwindling years; it vanished altogether right around the time Game Boy experienced its second wind. The Game Boy's immense library of software numbered 10 times that of the Lynx's, and that's not including the extensive release list for Game Boy Color, a sort of incremental revision of Nintendo's system.

There's a temptation, I think, to characterize the Game Boy/Lynx rivalry as a David-and-Goliath battle, all the way down to its inevitable outcome. Lynx, after all, had an absolutely hulking design — it literally dwarfed its rival, even once the more compact Lynx II model came along — and its tech specs exceeded Game Boy's in every respect save screen resolution. Game Boy's triumph reads like a biblical tale of inversion and victory in the face of impossible odds.

But in truth, that reading doesn't reflect the realities of actual history. Yes, Lynx was by far a more powerful system than the best-selling Game Boy. Nevertheless, Nintendo's dominance didn't represent the triumph of the little guy; it was instead a classic case of the big guy steamrolling a scrappy little competitor. Atari was David in this feud, crushed beneath Nintendo's giant, ruthless heel.

Crash and Burn

For those who cut their teeth gaming in the early '80s, the idea of Atari as the "little guy" seem almost counterintuitive. Atari practically invented the games industry: Coin-op hits like Pong paved the way for the golden age of the arcades, while the home version of that game established a consumer market... one the company transformed into a permanent fixture with the success of 1977's Video Computer System, the 2600. Atari handily outmaneuvered competitors like Mattel and Coleco; its stunning success caught the attention of media giant Warner Communications, which absorbed Atari as an extension of its home entertainment division. In the early '80s, Atari was as big as big could be.

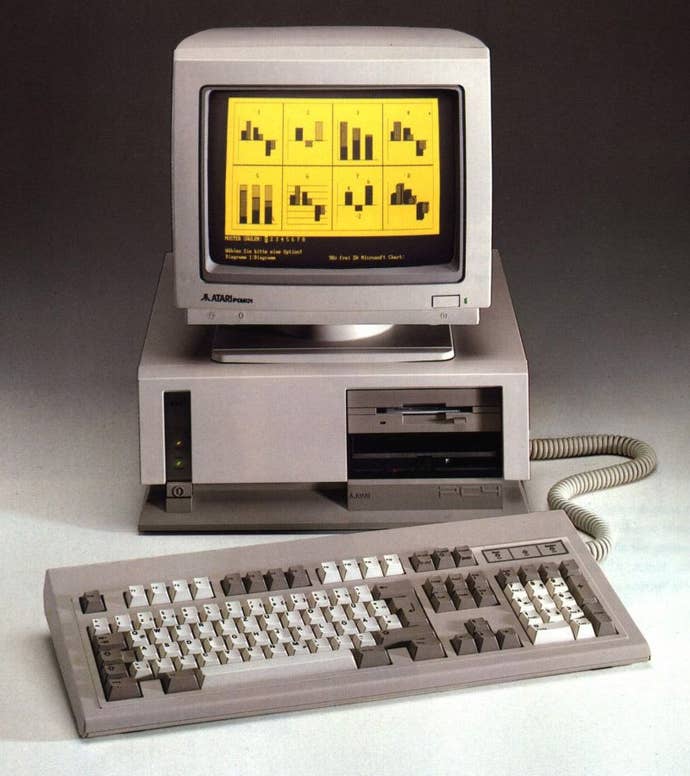

Yet's Atari's business imploded shortly thereafter, leading to the infamous "video games crash" that devastated the American console industry and crippled the influence of American games on the international scene right as those other markets stood at the cusp of their own booms. The vacuum left by Atari's collapse caused the European market to consolidate around a handful of locally made computer standards like the ZX Spectrum and Amstrad CPC. And, of course, it gave Nintendo a chance to rise to prominence in Japan.

Meanwhile, the one-time giant found itself divided and conquered. Warner eagerly divested itself of Atari, having suffered the worst financials of its entire existence thanks to the 2600's self-destruction. In the process, Warner broke its video game subsidary into two entities. Atari Games carried on the company's old-school tradition of producing arcade games, churning out a number of classic coin-ops in the back half of the '80s even as its controlling stakes bounced from owner to owner. Meanwhile, the home entertainment and computer division became Atari Corporation, run by exiled Commodore founder Jack Tramiel.

Neither half of the broken Atari ever managed to reclaim its former glory. Despite valiant attempts to keep abreast of the industry, including launching the "64-bit" Jaguar console in the thick of the '90s next-gen wars, Atari Corp. couldn't compete with the steely grip Nintendo had gained over the industry with its perfectly timed (and cunningly conceived) NES launch.

By the time Lynx debuted, Nintendo owned the console industry in both Japan and the U.S., claiming 90 percent or more of each nation's respective market. With that reach came a certain degree of power when it came to distribution and marketing; in fact, Nintendo came under fire more than once for alleged monopolistic behavior toward retailers. At any rate, the sheer popularity of the NES guaranteed its little sibling Game Boy would be given prime treatment at toy, department, and electronic stores.

Lynx, on the other hand, proved to be a harder sell. Atari Corp. had considerable clout with computer resellers thanks to the Atari ST series; the company's console presence, on the other hand, had effectively diminished into a memory. The 2600 and 7800 soldiered on as a cheap entry-level console and a would-be NES competitor, respectively, but they occupied forgotten corners of the game racks at outlets like Toys 'R Us and Kaybee Toys, if they appeared at all. Lynx would have to struggle if it hoped to make inroads into a market dominated by Nintendo.

The same held true on the development side as well. After Atari's 1983 wipeout destroyed dozens of smaller companies by way of collateral damage, American studios were slow to return to the console space, having found far more stable and profitable results in the growing personal computer market. The success of the NES drew a number of American companies back into the console space, but the early launch and success of the system in Japan meant Japanese developers had a considerable lead over Western developers on contemporary consoles. At the same time, the dominance of Nintendo in its homeland and a certain tendency toward nationalism meant almost zero Japanese interest in the Lynx.

In short, Atari and Lynx represented the underdogs in 1989, not Nintendo's Game Boy. All it really had to put up against Nintendo's reach, mindshare, distribution, and business partnerships was slick graphics and a unique (albeit small) library of software. In hindsight, it never stood a chance.

"I don't think [Atari] really could have done anything, really," says Origin Lead Writer Craig Harris, former editor of IGN Pocket. "We can play armchair quarterback and play the 'better games and cheaper price' retrospective game, but Nintendo was king of the gaming mountain back then and hit it big with an inexpensive system that offered Nintendo games in black and white. Oh, and Tetris."

The Plucky Upstart

Lynx's story actually began in 1986, when R.J. Mical and Dave Needle began developing a handheld game system for software publisher Epyx. As the architects behind the almighty Amiga, Mical and Needle knew a thing or two about delivering compelling and powerful hardware at prices that managed to stay just within the bounds of "reasonable."

Epyx had been one of the success stories of the post-crash era. When the U.S. console industry collapsed in upon itself, Epyx thrived by bringing arcade-like experiences to home computers. Hits like Summer Games and Impossible Mission turned Epyx into a publishing powerhouse.

Despite being known best for designing games, however, Epyx wasn't venturing entirely outside its wheelhouse when Mical and Needle came aboard to create the handheld system that would be codenamed Handy. The company had dabbled in peripherals and software tools that improved the efficiency of the Commodore 64's hardware. A full console was simply the next logical step.

Handy was poised to take Epyx into the lead in a sector of gaming no one had even begun to explore. Handheld games prior to that point had been humble affairs: Dedicated LCD units like Nintendo's Game & Watch, or primitive cartridge-based black-and-white systems (e.g. Milton Bradley's Microvision and Epoch's Japan-only Game Pocket Computer). The closest thing to a color portable were tabletop VFD (vacuum fluorescent display) systems that essentially worked identically to Game & Watch systems, but with limited luminous colors.

By comparison, Handy was to be a monster. Sporting a 16-bit processor, a color LCD screen capable of displaying more than 4,000 different colors, and advanced networking capabilities, Lynx was a more powerful system than the home consoles that launched around the time its development began (the Nintendo Entertainment System and Sega Master System). It didn't simply represent a step above its portable predecessors; it leapfrogged home systems as well, offering a natural harbor for conversions of contemporary arcade games.

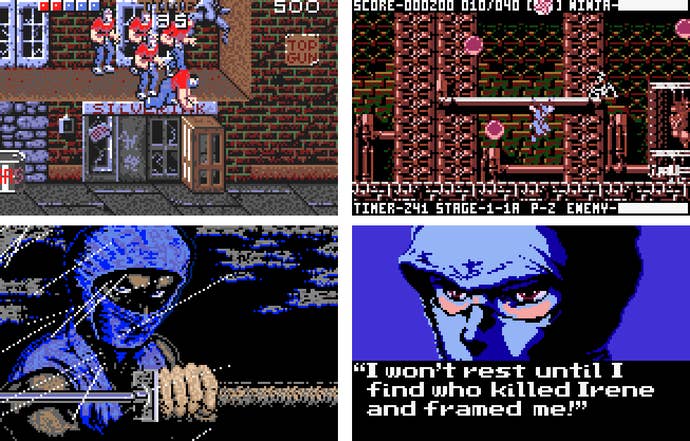

"The Lynx excelled at bringing the arcade experience home," recalls Lynx fan Diego Trujillo. "Atari was in the middle of a truly great period of incredibly fun and interesting arcade games during the woefully short Lynx lifespan, and they flawlessly brought the best of them to their handheld baby. I grew up playing arcade games, always yearning for the day the home experience wouldn't be a pale shadow of the glory of the arcade. In that respect, the Lynx did something that really no one else was really doing, and did it very well."

Unfortunately, Lynx's high specs also came with high costs. Mical and Needle delivered the handheld system Epyx had commissioned, but by the time it took shape the company was in no condition to manufacture and distribute it on their own. According to a NowGamer retrospective on the system, Epyx attempted to interest Nintendo in the system, but Nintendo already had its own portable device in the works. When that gambit failed, Epyx turned instead to Atari Corp.

Not surprisingly, Atari didn't require much convincing. As NowGamer notes, the company had experimented with portable games technology to no avail, and with only the aged 7800 to compete against Nintendo's NES, it was in a poor position to take on the console market. On top of that, Atari had already missed the boat on one pitch; years prior, Nintendo had solicited the Famicom console to Atari in the hopes that the American corporation's existing distribution network would give it an easy in to Western markets. Atari, however, found itself in the midst of a desperate struggle for survival and passed on the opportunity, leaving Nintendo to bring the Famicom to the U.S. as the NES. Nintendo hadn't simply resuscitated American enthusiasm for consoles; it had replaced Atari as the generic catch-all term for video games. Atari undoubtedly wanted to reclaim a piece of that glory, and Handy was a perfect vehicle for the company's return.

For Epyx, it would prove to be a deal with the devil. Atari brought the Handy to market, rebranding it as the Lynx, but the tradeoffs would be fatal for the company that conceived the system. By allegedly abusing the terms of the Handy licensing contract, Atari managed to strongarm Epyx into surrendering the rights to the console altogether. Epyx eventually disintegrated as a direct result of Atari's manipulation.

Slow on the Draw

Despite Atari's Machiavellian intervention, the system itself wouldn't come to market for another two years, despite having largely been finished well before that. In that time, Atari didn't tinker much with what was under the Lynx's hood, though they did come up with the utterly massive hardware design that many regard as one of the system's Achilles heels.

"In all the focus group testing, and we did a lot of it with consumers, we had a bunch of different models that we showed them," Mical recalled in an interview with 1UP.com. "[We asked] "which one do you like? Which one would you like to have it be?" We showed them big ones; we showed them little ones. We showed them gigantic ones; we showed them little tiny ones. They loved the big ones. They all told us, 'Make it big. Make it big. This one feels like it's substantial and I'm really getting my money's worth.' They all told us to make it big, so we made it big. And when it came out on the market, they all said, 'Why is this damn thing so big?' It'd drive me nuts, because the original Lynx was mostly air space inside. We put it in, because that's what they told us they wanted."

Lynx's unwieldy girth wasn't without its benefits — the system incorporated a clever ambidextrous design — but it had the significant drawback of rendering the machine not particularly portable. While it was friendlier to gameplay on the go than something like the Vectrex, Lynx couldn't be slipped into a jacket pocket or small bag the way the compact Game Boy could.

Lynx and Game Boy made for an interesting study in contrasts. While the two devices worked toward common ends — playing games on the go — they arrived at that destination with two very different philosophies. Game Boy was an exercise in minimalism and compromise, stripping down every feature to its most basic level. Lynx was about indulgence, not just in its size but its power and options as well.

"It was a very powerful console, ahead of its time, with a color widescreen style screen," writes Lynx owner Omar Garza. "While the SNES could scale a plane using Mode 7, the Lynx could scale the sprites. Visually, some of its titles were comparable to or better than what was available at that time on the NES and Genesis. Being able to connect 8 players or more was a great idea, but I bet no player at the time was able to find enough players with a Lynx console to make it happen."

The problem was that the system's feature-rich design made it a pricey option... and not just at the time of purchase.

"The Lynx had pretty terrible battery life, if I remember correctly," writes Supergiant Games designer Greg Kasavin. "In hindsight the genius of Nintendo's Game Boy was that it ran so much 'lighter' than systems like the Lynx. You could keep playing and playing, while the Lynx would flare out in a couple of hours. You'd end up playing it at home plugged into a wall, so the portable aspect of the device was rendered somewhat moot."

With a sticker price twice that of Game Boy and half the battery life, Lynx made for a tough sell despite its stunning graphical capabilities. Budget-conscious parents almost always take the path of least resistance to their wallets when it comes to buying games, something Nintendo itself has been forced to contend with in an era of mobile games that cost 99 cents, or even nothing at all. Had Atari launched Lynx well before Game Boy, it might have stood a chance, but head-to-head all the computing power in the world couldn't top a budget-friendly price.

Life at the Bleeding Edge

Lynx did benefit from having been folded into the Atari family. Despite being separate entities, Atari Games and Atari Corp. maintained a strong relationship, and many of the former's top arcade releases made their way in fine style to the system. Despite its low screen resolution, Lynx could display and scale an impressive number of sprites, giving an effect not too different from Sega's popular "Super Scaler" arcade titles. In fact, launch title Blue Lightning was Epyx's blatant ripoff of Sega's Afterburner, and it put most legitimate home renditions of Afterburner to shame.

"Lynx had a Blitter chip that helped it move big chunks of data around quickly, and because of that, it could bang out huge numbers of sprites, which it could scale and rotate with ease," says USgamer's resident Lynx enthusiast Jaz Rignall. "Robotron 2084 is a great example of how good the system was. Where other home versions were often lacking, the Lynx was a faithful recreation and featured a similar monster count to the arcade machine — all of which exploded in a spectacular way when you killed them."

"Warbirds, Xenophobe, Rampage, Rampart, California Games, Gauntlet...," muses Harris. "The Lynx system had some excellent network multiplayer gems. And it's hard to explain just how unreal it was to play these multiple-screen multiplayer games in a day when hardware these days does it wirelessly without breaking a sweat.

"The networking feature was phenomenal in games that supported it. I actually managed to get eight players together for an afternoon of Todd's Adventures in Slime World back in the game released in 1990. It's unreal. You explore the same underground world independently — imagine a 2D Metroid game with five other Samus Arans running around the same planet — and just the idea that we could either be in remote areas or in the same sector to help out our fellow player...it was something that no other video game system did.

Yet not everyone found themselves quite so taken with what Lynx had to offer. Whereas Nintendo's Game Boy quickly established a library at once both deep and broad, filled with everything from puzzlers to platformers to RPGs and bolstered by familiar names like Mario and Final Fantasy, Lynx offered arcade conversions and original — which is to say, unknown to casual consumers — creations. Initially, the Lynx's library consisted entirely of Epyx creations, and Atari and third parties were slow to populate the lineup with additional releases. Going into the systems' crucial first holiday season, Game Boy had nearly 20 titles available for purchase; Lynx had five. And of those, none offered the compelling allure of Tetris or the mascot power of Super Mario Land.

"Finding an Atari Lynx title that is actually a good game instead of an impressive tech demo can be difficult," states Garza. "I always got the impression that titles were developed by very small teams that lacked the vision of what a portable game should be. Arcade ports on the console tend to be good, mainly because they already had a tried-and-tested game design. Games like Warbirds and Todd's Adventure in Slime World are good examples of titles where the developers did not know how to make a single, unified game design, and so they overwhelmed the player with options and game modes that offered no reward, hoping the player would find the correct combination of options to make the game fun.

"Lynx did have a few good games, but not enough compared to other consoles libraries. Third party support was practically nonexistent. I can only imagine what the developers at Capcom or Konami could have managed to do with the console's capabilities."

While Atari claimed to have sold through the majority of its initial shipment in short order, Lynx sales quickly tapered off in the following years. Atari attempted to rectify the machine's shortcomings by releasing the Lynx II, a more compact version of the handheld offering longer battery life and a dramatically better sticker price.

The system never launched in Japan, and its European distribution was so scarce as to be nonexistent. European Lynx owner Uwe Spiller characterizes Atari's efforts overseas as, "shabby."

"The Lynx was nowhere to be found in physical presence, i.e. it wasn't stocked in stores," he writes. "You could mail order it (and the games) from video game retailers who did ads in magazines. So buying fun, quality titles was pretty much hit or miss. To my knowledge, it was really more a word-of-mouth thing among established young adult gamers who could shell out their own money to justify the purchase."

The Lynx did find a place among an enthusiastic niche who appreciated its raw power — Mical bragged that the system's specs went unmatched by any portable prior to Game Boy Advance — and it continues to thrive thanks to a small, dedicated homebrew niche. The console's list of rediscovered canceled titles and fan-made unofficial games is nearly as lengthy as the official releases. That's less a knock on the Lynx's legitimate library than a testament to the affection and tenacity of its fans.

It's hard not to look at all the strengths the Lynx offered and wonder how it could have gone differently had a few details been different — had the system made it to retail before Game Boy, had Atari worked harder to bring down the cost and power consumption of the machine, had they convinced more third parties to sign on as development partners. Could Lynx have become the handheld standard? Or would Nintendo's clout, cunning, and toymaker's instinct for what kids and parents would look for in a portable system have trumped Lynx's raw power no matter what? Given Nintendo's 25-year legacy of dominating the handheld market with inferior hardware, perhaps Lynx's also-ran status simply couldn't be avoided. Still, Sega gave Nintendo a run for its money in the console space with a Lynx-like focus on tech and arcade-style experiences; why couldn't Lynx have done the same in the handheld arena?

"I always see it as Atari throwing away so much potential," says Harris. "The company wasn't doing great when the Lynx came out, and even just a year later it was throwing all its eggs into the console basket with the rumored Panther and released Jaguar. And we all know how well that went. The company had gold with the Atari Lynx but it just faded into unsupported obscurity."

"I see the Lynx today as the first portable game system that was not explicitly intended for children," says Trujillo. "It was brought to market with the hope that its superior specs would woo an untapped section of the market, and find success through word of mouth. Pretty much every challenger to Nintendo's handheld dynasty has used the same strategy to mostly the same effect. Sadly, that's probably the Lynx 's legacy."