The Universal Systems of Tom Francis

Eurogamer's Tom Bramwell chats with the Gunpoint developer about how his game was always building inside him, even as he continued life as a critic.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

The last time I remember spending any proper time with Tom Francis was in early 2010. We were both in San Francisco to cover the announcement of BioShock 2 -- he was there for PC Gamer and I was covering it for USgamer's sister site Eurogamer -- and he is one of two people I remember vividly from that trip.

The other was the then 2K Marin creative director Jordan Thomas, who I can still picture in a corner of a dark room, addressing me from a leather armchair of inscrutable power, speaking eloquently and patiently about the intellectual rigor of the game he was making -- a sequel to a Ken Levine special.

You have to be a certain caliber of developer to get away with following Levine -- let alone improving on his work, as some felt BioShock 2 did -- and I remember I found Thomas slightly intimidating. Francis wasn't fazed, though. Indeed, the reason I remember him on that trip in particular is the sight of him, stone cold sober in a whiskey bar, chewing Thomas' ear off about how to make games.

Last month, Francis put his money where his mouth had been three years before, releasing Gunpoint, a 2D stealth-action homage to Deus Ex. Smart and funny, it embodies many of the things Francis loves -- players pounce around levels in a pair of superpowered spy pants, using a special Crosslink gadget to rewire light switches, sensors and elevators to outwit security guards and steal corporate secrets. It's been tremendously successful, securing him a future making games full-time.

"I think it's probably a safe policy not to say exactly how much it's sold," he tells me when we meet up in Brighton, UK for the Develop conference. "But really, really well. I have many years in which to make another game and I don't have to worry about my next thing being commercially safe or I don't have to worry about monetizing it. Well, I have to worry about selling it, but..." You don't have to read that white paper on monetizing children? "Hahaha, yes, I can skip Monetizing Children!"

Another person who will presumably skip that seminal paper is Jordan Thomas, who followed Francis into full-time indie game development earlier this month.

The thing people fixate on with Francis is that he has joined the ranks of game critics who have downed tools and gone into development, and there are some interesting things about that. The first is that he didn't actually down tools. He developed Gunpoint in his spare time, only leaving PC Gamer when it was clear the game was a hit, which is an incredible thing to have done.

The second is that Francis was an unusual critic. As he accumulated a body of work over many years, he seemed to be searching for something; some deeper understanding of the things he loved. Every critic does that from game to game, and perhaps we develop specific tastes along the way, but as one of Francis' readers I always got the feeling his ideas were likely to outgrow his medium. Now that it seems as though they have, when we meet up I want to trace how and why.

It turns out that it's quite easy to draw a line from Gunpoint back to one particular formative experience.

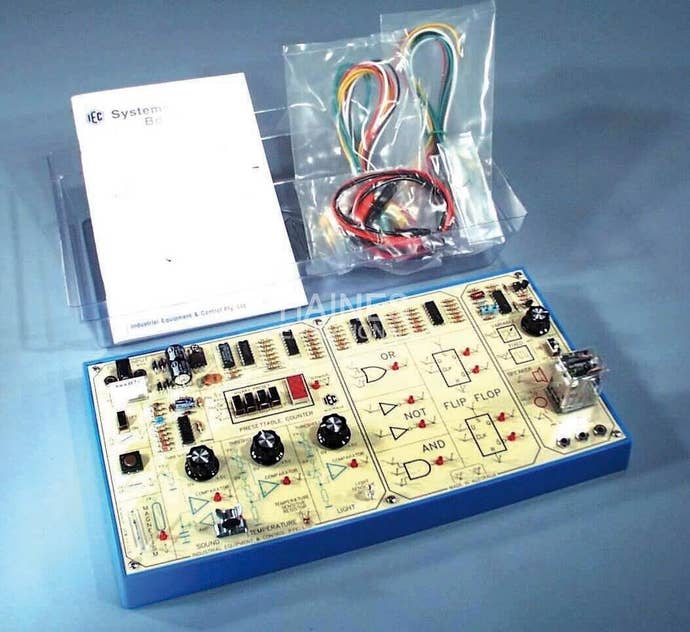

"I realised after I'd implemented the Crosslink in Gunpoint that it's almost exactly like an electronics kit my dad gave me when I was very young," Francis tells me. "That was just a big circuit board with inputs down one side and outputs down the other side. And then you had a bundle of wires and you choose how to wire them up.

"I don't know if I liked that toy because I already thought like that, or maybe I was just completely impressionable at that age and when I started playing with that toy that's what made me start to think about, 'Oh, it's cool when you have a set of elements and you choose how to combine them.'

"But looking back at it -- I haven't actually seen it since then -- and thinking about how it worked and picturing it in my mind, that's embarrassingly similar to the game I made! You can literally have a light switch connected to a light and decide to wire it differently to make it do what you want."

If that electronics kit was an influence that took a while to establish itself in his thinking, then Deus Ex was not. Many years later, Francis played Ion Storm's game and came to revere it above all else, as anyone who followed his games journalism will be able to attest. Which is funny, in a way, because when he first played it, he kinda hated it.

"I played the demo," he explains today. "I'd heard it was good so I was really trying to like it and I just got shot immediately, and I was like, 'This is a terrible shooter! This is rubbish!'" As he neared the end of the demo, though, he faced two guards in a corridor. "I was looking through my inventory for just anything that I could use, and there was a fire extinguisher. So I thought I could spray it at them. I ran round the corner, sprayed it in both their faces, and headshotted them both at point-blank range, and I was like, 'F***ing hell! That was brilliant!'"

He didn't quite know why, though. "Yeah, I think I didn't really know, or couldn't really articulate it at that time. I remember actually saying, 'Any game where you can spray a fire extinguisher at two people and then shoot them both in the head is automatically brilliant.' But I hadn't made the jump to why is that and what makes it so cool to me."

Fortunately, the cyclical nature of his job on PC Gamer and the long shadow cast by his favorite game meant he was able to spend his nine years as a critic honing his understanding of why he loved it.

"Every Top 100, even if it's not the number one spot, I'm the person who has to explain it, and because you've done it before you also have to come up with new reasons every year or every time you have to write about it... Obviously the more you think about it, the better your understanding gets of what's working about it."

As he wrote about Deus Ex over and over and fell in love with other games with similar principles -- Hitman: Blood Money and Supreme Commander are his other two favorites -- the elements that he enjoyed became clearer to him. They're particularly clear in Derek Yu's Spelunky, the procedurally generated 2D platform game, which Francis credits with inspiring him to start making a game in the first place.

"It gives you systems that work universally, or work in any context, and then doesn't try and predict the consequences of those," he explains. "It doesn't let you pick things up and then say, 'You can only pick up these and the reason you need to pick it up is to solve this picking-up puzzle where you must pick up the crate and put it on the switch.' It's just like, 'Anything you could reasonably pick up, I'll let you pick up, and anything you're holding you can throw.'"

Something that I find really interesting about Francis is that he doesn't just like this sort of game; he is almost paternally forgiving of games that function this way, even if they fall apart in others.

His reviews would often open with anecdotes about how some combination of systems allowed him to fashion a unique plan that led to hilarious, often useless consequences. Writing about Deus Ex: Human Revolution for PC Gamer, for example, he explained how he launched a spectacular attack on a group of gang members from a rooftop, throwing a vending machine into their midst and then landing nearby in a blaze of cybernetically enhanced fury, only for them to peer at him with disinterest and tell him to push off.

Meanwhile, he is powerfully repelled by any game that deviates from his favorite paradigms, particularly those where the story contradicts rules he thinks should be important and universal. "Here's an idea, guys," he wrote in his Call of Duty: Black Ops review. "Make a f***ing film. Get it out of your system, and come back to games when you're ready to give the player even the illusion of control." Gunpoint contains almost no scripted sequences.

"I do really like good stories," he tells me today, "but they're pretty rare in games, and what's very, very common is, even if the story is OK or good, it clashes with the mechanics and restricts the mechanics, and the systems that I'm really excited about [in the game in question] are not even universal.

"It gives you this gun and says the gun's really powerful, but then it doesn't work on this person because this person's important to the plot, so they can't die, so that system that was universal is now injured by that so it's not really a true universal system, and so now every mechanic that doesn't always work is another spanner in the works when I'm trying to think of a cool solution to a problem. So I usually end up irritated by stories in games."

As we continue to delve into what he likes, I get the feeling it's not just games that he feels suffer from story. I'm not convinced he's even keen on it in books.

"I guess most of the books I really like are quite light-hearted... There aren't many stories I like just because of the story -- it's almost always because of the writing." I don't think he means the writing in a poetic, beautiful sense, though, but more the way writers play with the structure, epochal events and your expectations.

"I don't mind a really long story," he says, "but it can't just be a short story with a lot of detail just crammed into the spaces between the actual events. I get impatient with that, so I don't get on with the Lord of the Rings books at all -- I'm just like, 'For f***'s sake, get on with it!'"

"I probably have more favorite films than favorite books," he says. Which films? "The stories I get most excited about are things like Memento, which I absolutely love, and Adaptation, LA Confidential... I guess obviously they have to get to the point because they're movies, so there can't be too much extraneous detail because I get impatient with it, but also I think maybe when you're telling a shorter story you can play with the format and the way you tell it in really clever ways, and you almost have to in many ways."

I point out that all the stuff we're talking about is in the same oeuvre. It spans a whole bunch of different genres and styles and mediums, but it's all structure, puzzles, systems. "We might have actually understood my brain," he laughs.

On that note, Francis is probably one of the few people -- not just game developers, critics or gamers, but straight-up people -- who can claim he actually does understand his brain, or at least how to make it do things. He's blogged entertainingly about his attempts to understand the logic of things like his moods, and if this is evidence of some sort of existential or midlife crisis -- "ageing and panicking", as he puts it -- then he's handling it a lot more coolly than most of the rest of us.

"The main thing I cared about in a review was always that my analysis has to be correct and I have to really deeply understand what is and isn't working about this," he notes. "That's the same kind of thought that I find myself applying to everything, including my own life." If that sounds strange, go read a couple of his posts. This is just how he sees the world.

Eventually we come to Gunpoint itself. To me, it's the sum of Francis' tastes in everything. It has universal systems, and although it has a story, that story is kept off to one side, completely skippable, so that the player can create his or her own adventures. Francis still enjoys it, despite working on it feverishly for three years, and when I ask for an example of why, he reels off a trademark anecdote, the sort of thing you can imagine him writing in a review in PC Gamer.

"I was trying to get past one guy who was standing in front of an open door and had nothing to interact with," he explains. "It was just me and him. He was facing away from me." Through the open door there was a light switch, which he could rewire with Crosslink to close the door, but that would be useless if he couldn't get there. In classic Tom Francis fashion, he was playing the game his own way -- refusing to touch anyone else in the level, just to amuse himself.

"I climbed up the wall behind him and did a maximum-strength jump directly in front of him. So I'm coming down over his head and landing in front of him, skidding through the open door, and then I hit the light switch as quickly as I can so the door closes behind me and he can't shoot me. So he just sees a guy suddenly appear in front of him, skid across the floor and slam a light switch. The door shuts and then he runs to it and he can't open the door. I got away with it. Yes! That was perfect!"

If Gunpoint is the sum of Francis' tastes, though, his tastes are the reason why it exists. "I think probably they relate a lot to the fact I wanted to make a game in the first place, and the fact that I ultimately did," he says, when I ask him what his preferences as a gamer and developer say about how his brain works. "I stuck with it and I kept tinkering, because it's a game for people who like tinkering, and the games that I like are not about how to play the game the best way, but just to find new ways to play games. Just to experiment."

In some ways, Francis has come a long way from that whiskey bar in San Francisco three years ago, but in others he's come no distance at all. He was always inventing games -- as a child playing with his electronics kit, in his writing as he hatched plans and made his own rules in Deus Ex and Spelunky -- and the clash of different mechanics and their interesting consequences has always propelled him forward.

Now he's simply making the universal systems as well.