After early promise, is The Tomorrow Children digging itself into a hole?

Immaculate Cold War stylings can't hide the drudgery of busy work in this PS4 exclusive, says Dan Pearson.

"It has a beautiful brutalist aesthetic, a rousing, sturdy choral hymn of visual references which pulls together some of the best artistic and technological visions from both sides of the Cold War Curtain, albeit with a hefty Soviet spin."

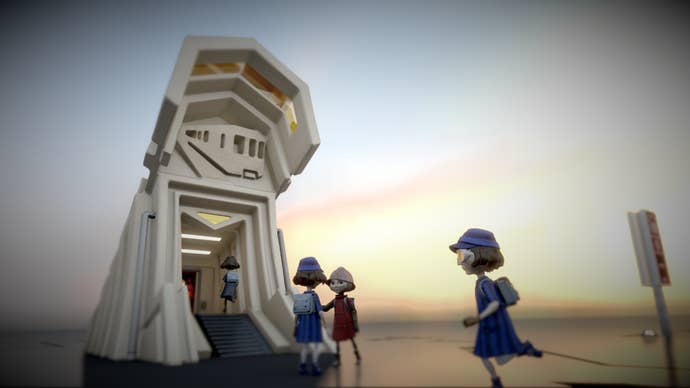

When I saw the first trailer for The Tomorrow Children, I was smitten. It has a beautiful brutalist aesthetic, a rousing, sturdy choral hymn of visual references which pulls together some of the best artistic and technological visions from both sides of the Cold War Curtain, albeit with a hefty Soviet spin. It's the Jetsons, imprisoned in Terry Gilliam's Brazil for expressing non-conformist ideas, a clockwork Epcot centre bristling with happy peasants on jetpacks. It’s simultaneously grimy and oppressive and very beautiful, reminiscent of Little Big Adventure and early Double Fine. I was excited.

But. Pickaxes. Pickaxes are the new crates, the modern exploding barrel. Because crafting is now a mandatory feature of anything that wants to call itself a video game (thanks Notch) pickaxes are absolutely everywhere, a tool-based shorthand that says "Hey, you can smash the world and make it into stuff! How cool is that?" And often it is pretty cool, you know? Bringing your hand to bear on the natural landscape and refurbishing it in your own vision is a beautifully Ozymandian expression of one of the things I love most about games - the freedom, the creativity, the happiness of a good toolset and a few hours to spare. But it’s ubiquitous, and in the ADD world of games, that means boring.

That’s often because the pay-off of creation has to be preceded by the slog of production, which means digging. I don’t think anybody enjoys digging, not even the 895 billion people who play Minecraft. It’s quintessentially dull, the very epitome of mindless donkey work. Tap tap tap. Tap tap tap. Tap tap tap. Tap tap...crumble. Well done, you got some mud. Live it up, hombre! Finding stuff afterwards can be exciting. Building stuff with what you find can be exciting. But we should not conflate the work with the reward, because the digging itself? S**t.

Sadly, The Tomorrow Children is largely about digging. And that’s disappointing.

It does have a good stab at making it interesting. You play as a quasi-extant projection of a worker, a sort of Matrix-drone in a non-corporeal world created from the nebulous, amalgamated consciousness of humanity after a Soviet experiment gone wrong. Predominantly it consists of Void, a grey goop which spreads from horizon to horizon, punctuated only briefly by plucky constructivist settlements and bizarre islands of material, piles of giant shoes or gaudy primary-coloured geometric primitives.

"It took me a while to work out whether the multiplayer aspect was real at all, or if it would be revealed to be a sham, some sort of commentary on the fundamentally illusory nature of societal co-operation."

As a new worker, you’ll be shuttled out into the Void and delivered to a settlement, connected to each other by a metro system. If you’re not happy with your new home, jump on the underground and find a new one, perhaps one where you can make more difference, or one where you can freeload like the capitalist pig you are. Find somewhere to settle down and it’s time to start building for the betterment of humanity.

Like most great journeys of self-discovery and personal growth, it begins by catching a bus. Venturing into the void on foot is possible, but slow and dangerous, with the greyness turning to a fatal quicksand once you’re more than a few seconds out from the boundary of your town. The glorious people’s omnibus instead takes you directly to where the action is happening: the nobbly excrescences of material which pepper your world.

Hop off the bus at one of these islands and you can start to gather materials for building, collecting the usual wood and metal from the usual trees and outcroppings of ore. Different tools collect in different ways, allowing you to automatically create stairs or tunnels in the islands as you search for the treasures they conceal, but it’s all much of a muchness, a process which feels tediously familiar. Hit a vein with a pickaxe until it vanishes, replaced by a few nuggets of whatever. Carry these back to the bus stop and you can either drop them there, leaving them to an automated process which returns them to your settlement, or jump on yourself and see the job through to its end.

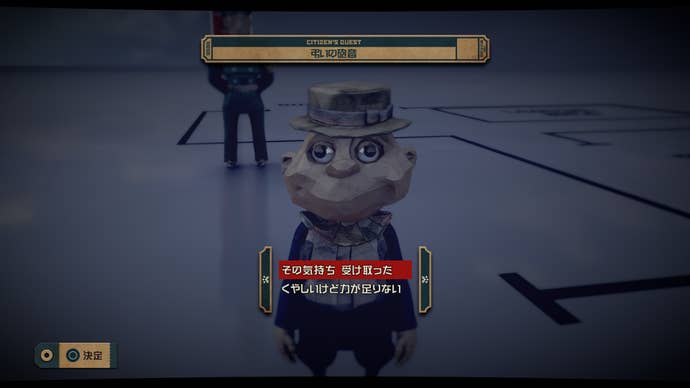

And... Well, you know where it goes from here. Get enough stuff. Build things. Get rarer stuff, make rarer things. Defenses, residences, shops and weaponry. There’s an interesting twist here, though - because this is a land of glorious socialism, you can’t just wade into the pile of communal resources and start knocking up a town hall like you’re the mayor. Instead, the other residents of the asynchronous multiplayer universe will vote on what to build next until consensus is achieved. Apparently. In the three hours I managed to spend on the game when the servers were up, I saw no evidence of my choices being contradicted, but then my town was pretty quiet.

In fact, it took me a while to work out whether the multiplayer aspect was real at all, or if it would be revealed to be a sham, some sort of commentary on the fundamentally illusory nature of societal co-operation. Other player’s avatars phase in and out of existence, popping out of the ether to help you dig out a node of metal or to pick up the ore that results. When they do, you can snap off a quick salute or a swift snubbing, according to your whims. It’s a slight and not particularly concrete form of interaction, particularly for a game which purports to be about collectivism, but it does contribute to the otherworldly atmosphere and mundane surrealism.

You’ll see your cohorts popping up on the resource islands (which crumble to dust shortly after being exhausted, to reappear elsewhere) or trotting around town, but there’s no real impression of inhabiting the same reality, let alone the same town. Building a town is all about the satisfaction of shared labour, but it’s hard to feel like you’re really collaborating on a grand municipal project when your fellow workers are all spatio-temporally dislocated phantoms. There’s no way to coordinate your efforts or to make joint decisions and it quickly becomes the town planning of the sensorially deprived.

"There’s no challenge to the fundamentally boring collection of materials, which means you spend most of your time in an assembly line state of mind rather than being engaged in a creative endeavour."

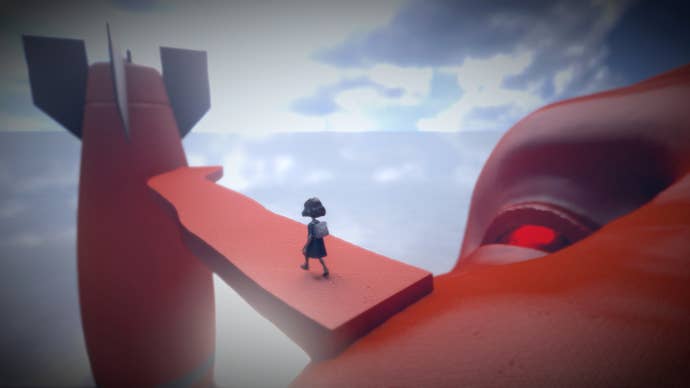

There are aspects of the game which give you more of a sense of a shared experience, however. Giant neon and chrome megafauna roam the grey wastes: massive godzilla-esque kaiju and flying manta rays, seething metal spiders and things that look early drafts of Star Wars’ Watto. These 'Izverg' are generally fairly aimless, but will occasionally take notice of your town and come looking for trouble. When they do, it’s up to you and your brethren to take up arms against them, occupying laser turrets or wielding shotguns to bring them down. Once murdered, they duly yield up more materials - shiny green crystals which are the mainstay of many of the more advanced buildings.

It’s a tremendously difficult thing to judge from such a short period of exposure. There was no time for me to become attached to my fledgling settlement, to get to know my ghostly neighbours. People flitted in and out, disappearing into the subway as they sought brighter lights and bigger cities. There was no pride when a new building rose from the glop, no shame when a massive reptile knocked seven shades out of it five minutes later. It felt transitory, fleeting, a little vapid.

Because buildings are prefabricated, with no challenge to creation other than a sliding block puzzle which has to be completed before you’re granted a blueprint, there’s little sense of having actually done anything. There’s no challenge to the fundamentally boring collection of materials, either, which means you spend most of your time in an assembly line state of mind rather than being engaged in a creative endeavour. It’s pickaxe syndrome writ large.

And yet… It’s still an interesting game, somehow, carried by its oddness and quirky charm even as it’s rebuffed by repetition. There’s promise here, but it’s not been brought to the surface just yet.

Impressions based on The Tomorrow Children closed beta, which ran from Jan 21-23.