The Strange Origins of Your Favorite Japanese Game Developers

We all had to start somewhere—and these directors started in some pretty inauspicious places.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

Very few game directors make a name for themselves with their debut. Even Nintendo's resident genius Shigeru Miyamoto first fumbled with Radar Scope before turning those forsaken cabinets into the immortal arcade classic Donkey Kong.

In most cases, developers toil away in obscurity for years before earning the chance to turn their unique vision into a reality. The following Japanese directors have been responsible for the best and most important games in our medium, but, like most superheroes, they began their careers in some pretty humble places.

Shinji Mikami

Capcom Quiz: Hatena? no Daib?ken | Game Boy | 1990

Quiz games never really caught on in America—outside of ancient, beer-coated machines bolted to bars—but in Japan, they've always been a pretty big deal. So it's not surprising to learn former Capcom director Shinji Mikami (best known for creating the Resident Evil series) started his career at Capcom working on one of these productions: After all, something as basic as a quiz game seems pretty hard to screw up. And, as quiz games go, Hatena? no Daiboken is pretty basic. Outside of the Capcom-themed board game framing device, this 1990 release doesn't do much other than present a series of questions about pop culture of the era. (Though it's probably the only time we'll witness Dr. Wily and Damnd from Final Fight sharing a cover.) We wouldn't get to see Mikami's knack for game design until the following year with the Game Boy's Who Framed Roger Rabbit?, which has the distinction of being the only video game adaptation of the classic 1988 movie that's worth playing.

Yuji Naka

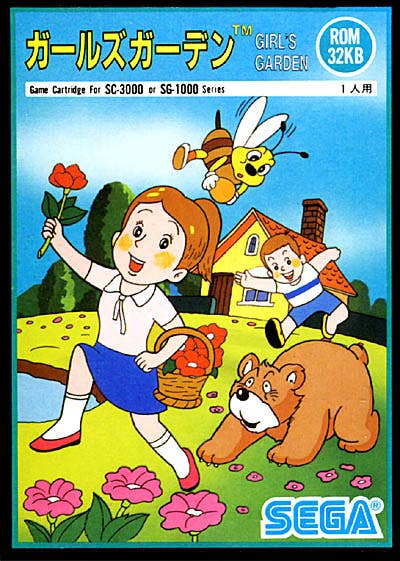

Girl's Garden | SG-1000 | 1984

Though a little guy named Sonic the Hedgehog put Yuji Naka—and the Sega Genesis—on the map in 1991, he began his career seven years earlier with an obscure little game called Girl's Garden for Sega's SG-1000 console. All in all, it's a cute, simple experience with a somewhat questionable message: As Papri, you're tasked with collecting a certain number of flowers in a stage—while evading deadly animals—before your boyfriend literally wanders into the arms of another woman (which is depicted in the UI). If you dig past its cutesy, storybook exterior, Girl's Garden comes shockingly close to being a codependent relationship simulator—though it does make for one of the more technically impressive games on the shockingly primitive SG-1000. Questionable content aside, Girl's Garden helped Yuji Naka prove his worth at Sega, where he would go on to be known as one of the best programmers in the business.

Hideki Kamiya

Arthur to Astaroth no Nazomakaimura: Incredible Toons | PlayStation, Saturn | 1996

Platinum Games' Hideki Kamiya made a name for himself with Devil May Cry and its progeny: stylish, fast-paced, and ridiculous action games that make players feel like total badasses. But his career at Capcom began with a very non-Kamiya production: a Ghosts 'n Goblins-themed version of Incredible Toons, a spin-off of the beloved PC classic The Incredible Machine. And Arthur to Astaroth doesn't deviate much from from The Incredible Machine, outside of the Ghosts 'n Goblins-themed trappings—you're still solving puzzles by building elaborate Rube Goldberg devices. It wouldn't take Kamiya much longer to prove his worth at Capcom, though. His role as system planner on the original Resident Evil elevated him to the status of director for the fantastic sequel, even if it took a few tries to get things right.

Yuji Horii

Love Match Tennis | NEC PC-6001 | 1983

Yuji Horii created a Japanese cultural touchstone with Dragon Quest, a revolutionary RPG that streamlined the mechanics of its PC contemporaries for an experience much friendlier to the console crowd. And that's not all he's responsible for: Horii also created the template for Japanese adventure games with 1983's highly influential Portopia Serial Murder Case, which did much to inspire the Ace Attorneys and Danganronpas of our modern times. Shortly before this, though, Horii first entered the industry with Love Match Tennis, a game he submitted to an Enix-sponsored game design contest in 1983—crowdsourcing isn't exactly a new idea. Love Match Tennis looks pretty primitive more than 30 years later, but it was impressive enough at the time for Horii to get his foot in the door at Enix, where he would go on to be one of the most prominent developers in the Japanese gaming industry after just a few short years.

Hidetaka Miyazaki

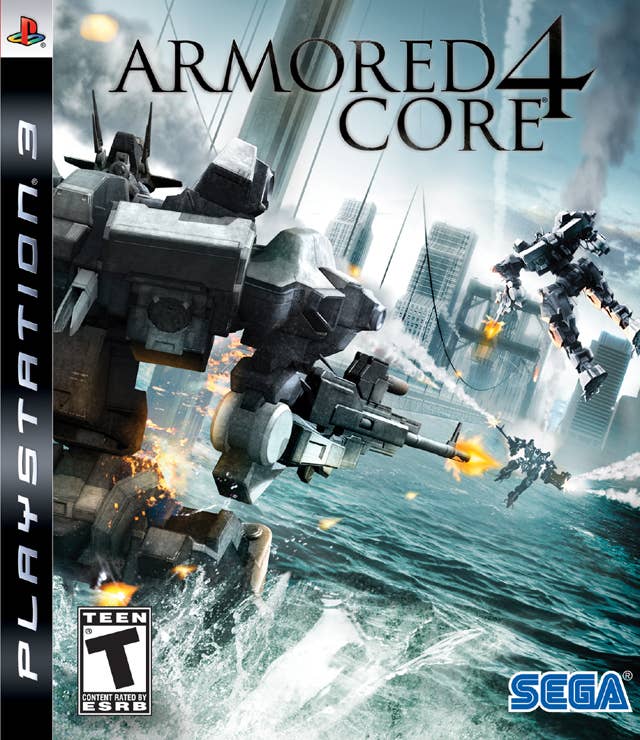

Armored Core 4 | PS3, Xbox 360 | 2006

Much like the narratives of his Dark Souls games, the life of the reclusive Hidetaka Miyazaki is shrouded in mystery. But what we do know makes him a pretty interesting figure: After playing 2001's Ico, he left a lucrative job to start from the bottom at From Software in 2004. It didn't take Miyazaki very long to earn the title of director, though his initial duties took him pretty far from the RPG action of the Souls series. After a few years of working in the programming mines at From, Miyazaki made his directorial debut with 2006's Armored Core 4, a sequel that garnered extremely mixed reviews from critics at the time. Miyazaki directed another Armored Core before moving on to 2009's Demon's Souls, but he's never forgotten the series that got him to where he is today: If you look hard enough, you can find references to From's robot-battling series sprinkled throughout the Souls games.

Hironobu Sakaguchi

The Death Trap | NEC PC-8801 | 1984

Square did its share of puttering around before going independent and kicking off the hugely popular Final Fantasy series in 1987. But creator Hironobu Sakaguchi—whose name is basically synonymous with "JRPG"—started his career developing text adventure games, a huge genre for an era in which early computers had a hard time pushing graphics around the screen. Sakaguchi's first production, 1984's The Death Trap, strays pretty far from Final Fantasy's Dungeons & Dragons-inspired source material: it's essentially a Cold War-era spy thriller. And while text adventures aren't the most exciting thing to stare at in the world, Square went the extra step by including glorious (kinda) full-screen images—which wasn't always the case in the early '80s. The sequel, Will: The Death Trap II went on to be Square's first commercial success, though their dabbling in text adventures wouldn't last much longer than the mid-80s.