The Stars His Destination: Chris Roberts from Origin to Star Citizen

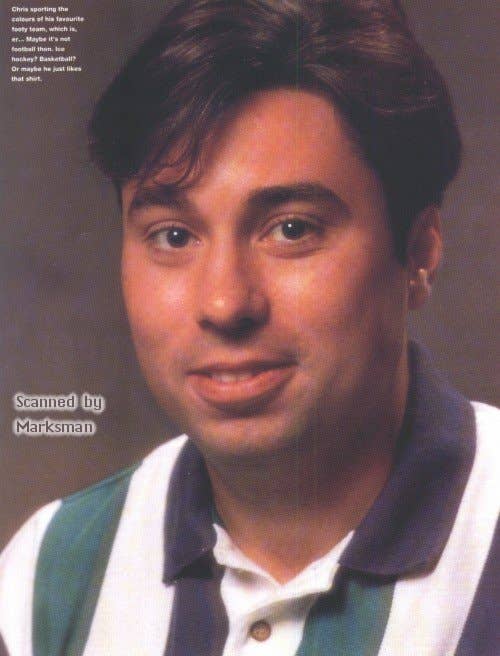

We follow Wing Commander creator Chris Roberts from his days at Origin to Star Citizen. Oh, and we ask about a certain movie he made.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

Words by Ian Dransfield.

It's a risk to move across an ocean to start a new life, even if the weather you're escaping is terrible. It's even more of a risk to give a young man free reign on an ambitious space simulator that allows you to embody a new virtual life. And it's still more of a risk to put everything on the line and ask a community you haven't been involved with for a decade to give you millions of dollars so you can make, again, a new virtual life. Chris Roberts' story truly is one of risks.

Growing up in a small suburb of Manchester, UK, avoiding university, getting away from bad weather and choosing to avoid big publishers offering millions of dollars. It doesn't read like the traditional route to making your dream project.

But that's just how it happened for Chris Roberts, the man best known for his work on the much-loved Wing Commander. Today he and his team of around 270 are hard at work at Cloud Imperium Games developing the game that has raised the crowdfunding bar to unheard of levels: Star Citizen.

Born in 1968 in Redwood City, California, Roberts moved across the Atlantic when still an infant—the Manchester United soccer team supporter considers himself thoroughly Mancunian—and began working on his first games when he was still very young.

"When I was young, I was an artist," Roberts tells me, "I enjoyed drawing comics and so on, and at my father's university they got a computer—I think it was an Apple II—I would go in on the weekends and be fascinated about how you could have games on it and you could animate stuff. That's how I had an interest in how to program, so I could figure out how to animate imagery."

His father, noticing the younger Roberts' budding interest in the dark arts of programming, quickly signed his eldest son up to an extra-curricular class at Manchester University. Around the age of 12, Roberts began to learn BASIC. It wasn't long until his youthful imagination-along with that of a friend-began making games: "I went with a friend of mine and we were at the back of the class, while they were teaching boring database stuff like how to file phone numbers or something, we were trying to program games like a helicopter game, or an oil rig platformer where you had to shoot at something."

Remarkably, this tinkering-and ignoring the teacher-didn't get him into trouble. Instead, it got Roberts his first paycheck: "The next year, the teacher of that class became the editor of The Micro User." He remembered that me and my friend were in the back of the class trying to make games, so he called up and asked if we'd like to write a 'game of the month' for the back of the magazine. In the old days they'd put a game of the month in the back of the magazine that you could type in in BASIC."

For the princely sum of £100 ($160), Roberts made a King Kong game, which he titled "Kong."

"It was, basically, King Kong on the Empire State Building and you were flying a helicopter and had to knock him off while he was throwing rocks at you. Oh, and you had to save people. That was the first game I did," Roberts remembers.

One more game for The Micro User later, and young Roberts officially had the bug. He was already a professional game-maker and hardly even a teenager. The adolescent talent eventually created games with titles like Wizardore, Match Day and Styker's Run for the BBC Micro [a computer from that era], but the platform soon lost its luster.

Origin

In the mid-1980s, Roberts' family left behind the grey clouds of Manchester for the last time and moved to the U.S. Roberts was attending Manchester University at the time and opted to stay behind, but it wasn't long before he went to spend time with his parents in Texas.

"I was at my parent's house in America which had a separate little studio. I set up my computer, got an IBM, figured out how to build a cross-development system so I could compile and work on the IBM, then put it across onto the Commodore 64," Roberts remembers.

"At that time I really liked the BBC Micro, but it really was just for the UK," Roberts says, "So the number of units you could sell wasn't high. I got a Commodore 64 and was teaching myself how to program and use a C64, because that was all around the world so you could sell a lot more copies."

At the time, the 19-year-old was working on Ultra Realm, the precursor to what would become his first "true game," Times of Lore. But a mixture of talent and, really, blind luck soon conspired to bring Roberts into the orbit of one of gaming's preeminent designers: Richard Garriott.

The meeting came about in part thanks to an artist named Denis Loubet, whom Rorberts engaged to help with Ultra Realm: "There was a local pen-and-paper role-playing place in Austin—I forget the name of it now—and I saw this picture on the wall and thought it was really good, so asked who did it. They told me it was a freelance artist called Denis Loubet, so I got hold of him and said, 'Do you want to do some work for me? I'll pay you to do something on this game I'm working on'."

Loubet agreed-the beginning of a working relationship that lasted into the midst of the Wing Commander series-and began working on Times of Lore. It wasn't long though before Loubet was hired on as a fulltime artist at nearby Origin Systems. That might have put the brakes on the game's progress, instead it opened the doors to Roberts' largest opportunity to date: "[Loubet] told them, 'I'm happy coming to work, but I've got this contract I'm doing on this other game, so I need to continue that.' They said it was fine and suggested they meet me. That's where I met Richard Garriott for the first time."

Though they didn't necessarily know it, Garriott and Roberts had a good deal in common. Both had roots in England-Garriott in Cambridge and Roberts in Manchester-and both had started developing games at a comparatively early age. Garriott had gotten his start in the 1970s developing games for the Apple II, which he sold in ziploc bags at a local computer chain, after which he developed the seminal Ultima series. Along with his parents and his brother, Garriott had founded Origin to handle the distribution of his suddenly very popular games.

Garriott liked what he saw from the young programmer, but as it turned out, Roberts had already pitched Times of Lore to the big publishers of the day: EA and Broderbund. But after mulling it over, Roberts opted to go with Origin. "The EA offer was for more money and all the rest of it, but with Origin I was already there in Austin, I really liked Richard, Denis and I could get to work on [Times of Lore] full-time, and I was like, 'Ah, I'm 19, I'm young, if it doesn't work out I can go to EA or something later on'. So I walked away from the richer deal to do the Origin stuff."

In retrospect, it was the right choice. Even now, Origin Systems is still remembered with reverence in the game industry, having been home to some of gaming's most well-known names. Roberts and Garriott, Warren Spector, Tom Chilton, Sheri Graner Ray and even, briefly, John Romero all plied their trade in the studio at some point—among many others.

During his time at Origin, an encounter with another development luminary, Sid Meier, was to change Roberts' entire views on game development. At a press day in Microprose's offices in Baltimore, Maryland, Meier showed Roberts his then-current project: F-19 Stealth Fighter.

"He showed it to me on this 386/25 which at the time was something like a $10,000 computer that had just come out and only three people had it," Roberts laughs, "It was completely mind-blowing, amazing, but nobody could play it. But it came out and all the reviews were effusive about how amazing it was... That was the moment that I was like, 'Sod this, trying to make it work for the lowest common denominator—I'm just going to try and push it'. This was the inspiration for Wing Commander in certain ways."

Joining the studio in its still-early days, being surrounded by an environment of creativity and enthusiasm, working in a small team, being inspired as so many have by Sid Meier and with everyone simply getting along ("Basically everybody went to lunch together," Roberts remembered, "It wasn't five people working on a game, it was five people working on three games. There was this really tight-knit spirit"), Roberts was free to unleash his dream project on the world. Though first it had to go to the bosses.

"The day Chris Roberts came in to pitch Wing Commander, was one I will never forget," Garriott tells me, "He had already mocked up the ship launch sequence: running down the launch bay, climbing into craft, closing the canopy and launching into space. It was obvious to all who saw it that this was a winning formula. It was obvious that Chris was a true visionary."

Roberts explains why his idea seemed so complete from the get-go: "Most of the time when you make games you have to tweak and polish, but on Wing Commander we'd done the tech demo, designed all the missions out on paper, and literally the game that shipped was the game that went in first time... The game that shipped was the game I wanted it to be in my head."

Not only did it come out right, it was appreciated and loved almost universally, even by its creators: "I would say that Wing Commander was the result of my previous eight years game development," Roberts says, "I tried all these different things: what worked, what didn't, what I wanted to do, and for whatever reason, Wing Commander became the perfect storm."

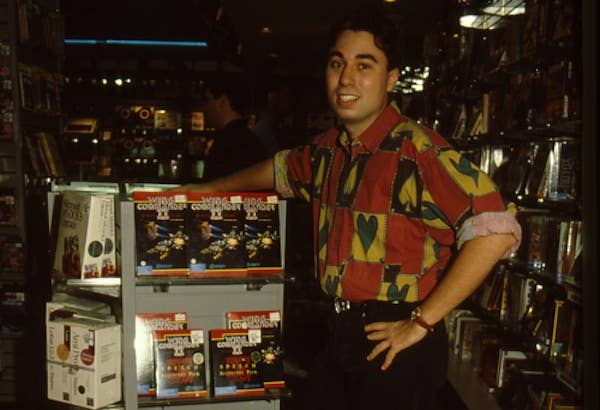

After Wing Commander and its amazing success came a more ambitious sequel that attempted to up the drama, including more in the way of storytelling and a broader branching narrative. Wing Commander II was the result. But from there Roberts wanted to take it further.

"When we'd done Wing Commander II it was still very Saturday morning cartoon in terms of the animation level," Roberts says. "One of the programmers working for me, Jason Yenawine, had been working on a compression method to play back video [on CD-ROMs]... For the time we thought it was good. Now it's pretty awful, but back then we were like, 'Oh yeah this is awesome!'

"I'd been feeling like I wanted the animation and story quality to increase, so based on this tech I thought I really could combine some live action where I could get some more performance and more human connection from the characters with the gameplay."

This 'bigger and more ambitious' move had always been on the cards, but Origin's sale to EA in September of 1992 wasn't a part of the plan: "I didn't want to sell Wing Commander to EA," Roberts admits, "But the terms of the deal were that they were buying Origin and they had to get Wing Commander and Ultima. It was a dealbreaker if I said no, and if I said no a lot of other people that had helped to build the company up over quite a long time would have their payoff for all the hard work destroyed."

So Roberts agreed, the sale went through for $35 million in stock, and for good or for ill, the EA/Origin era began. Soon enough, Roberts was greenlit on his next Wing Commander project-the third game bringing in real life actors and showing off FMV cutscenes with aplomb. It was EA's first million-seller on DOS and a worldwide hit, and Roberts is still grateful to the publisher for allowing him the chance to make it.

"I wouldn't have been able to make Wing Commander III without EA buying Origin," he says, "In terms of pushing what I did with Wing Commander, I wouldn't have been able to do it without EA's backing-that's the plus side of it. The downside is as you get bigger and become more beholden to things like, 'We need the sequel here, and we need you in this release window.' It feels like you're in a machine versus creating stuff that you're really 100 percent excited about."

Another sequel followed at EA's behest, taking around 13 months to complete. It was a success, but it showed Roberts that Origin was moving in a direction he wasn't particularly interested in. In 1996, when his EA contract expired, he left on amicable terms to begin a new chapter in his life as a creator.

Forging a New Career

After Roberts moved on from Origin, he quickly setup Digital Anvil with backing from Microsoft and AMD and began work on his next project.

"it just felt more like, when I was at that age, about 27, I just felt like I wanted a change," Roberts says with a shrug. "I'd been at Origin for nine years—it had changed quite a lot in that time."

Digital Anvil saw mixed fortunes in its relatively short lifetime. While the games it released were generally well-received, they weren't too numerous. Starlancer, made in partnership with Warthog Games, was the first release, but the company is mostly remembered for the often-delayed Freelancer—a project which wasn't even finished by the time Roberts left the company in the early 2000s.

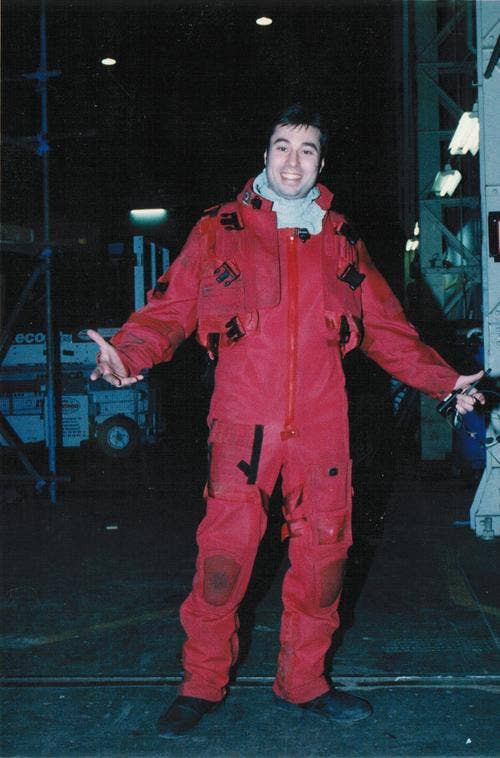

He also made a movie.

Directed by the 29-year-old Roberts, with digital effects provided by Digital Anvil and starring teen idol Freddie Prinze Junior, the Wing Commander film should have been the cherry on top of a sparkling career-an ultimate ambition fulfilled. Instead, it was a flop. A huge one.

Today, Roberts is sanguine about the reasons it just didn't work: "In the game business I had a lot more power and clout when I was doing filming stuff towards the end. Whereas in the film business I was a first time director and there were some issues."

Aside from being given a budget amounting to half of that other sci-fi films were getting, running out of money and having to axe a major character, and not being given the time to fix the Kilrathi ("They're not very good"), Roberts faced other difficulties. A producer who acted as a good deal-maker- but not one very helpful for a first-time director, for example.

And of course, it didn't help that he was a first-time director. "Movies are all about detail and texture-they're all about moments, feeling and emotion, and all that stuff isn't immediately obvious if you're a first time director."

Nevertheless, he remains positive about some aspects: "Robert Rodriguez is a friend of mine, when I first showed him the early cuts he was like, 'How did you do that shot? I'm going to steal that for Spy Kids!' Maybe he wasn't stealing my storytelling sense, but at least my shots-that's not bad!"

Roberts isn't making excuses to me, though-he recognizes the film has a lot of flaws, one being the general look of the thing, which rubbed series fans up the wrong way: "Star Wars was an inspiration for the Wing Commander games, so I didn't want people saying it was just a Star Wars clone. Instead I went for a very literal 'World War II in space' look, but all the people who grew up with the games were used to [it] looking a certain way.

Beyond that, he was more direct in this reflective critique: "I don't think I was particularly good at the nuance or subtlety that I think you need for movies, or also understanding how to focus your time and resources... I wasn't particularly happy with the movie myself."

Basically, it didn't work, even if all the intentions were good. The cast was wrong (Roberts said of Prinze Junior "He's a really nice guy, but for the character that I saw in the film he wasn't right"), production was difficult, and generally speaking it just didn't go to plan.

But it didn't put Roberts off: "I won't say I wouldn't do it again-I actually did have a lot of fun, I just want it to be what I see in my head next time."

His love of film undented, Roberts segued into the world of movies full-time after Microsoft purchased Digital Anvil, producing films like Lord of War, Lucky Number Slevin and Outlander. His time in the world of production was enjoyable, he tells me, and involved being on the ground, working on-set and helping directors achieve their vision-whatever it might have been.

"What I enjoy is developing a script," Roberts says, "I hate dealing with agents. I hate dealing with lawyers and financiers. That sucks. I love pre-production, production and post-production... For me I really like to be on the set. I view it like, if I'm not directing, my job is to help and support the director and be the overall big picture person."

Explaining why he enjoyed it, Roberts continues: "It's something that fun because movies are pretty in-depth. Games take years to make, whereas movies, once you've got your script and you're up and running, you can make even a big move in about a year. It moves pretty quickly when you're on set, lots of things are happening, you start to see early edits. For me, the on-set stuff and sitting in the editing room and the pre-production stuff sitting there with the art department, doing set design and working stuff out-that's by far the most fun part of movie-making process."

But there was an itch that moviemaking wasn't scratching. The technology behind games had moved on to a point where the vision Roberts had always held onto could be realized, and emerging trends outside of the gaming sphere meant that he would be able to follow through with them. After 10 years in the gaming wilderness, Chris Roberts made a triumphant return.

When You Wish Upon a Star (Citizen)

"I honestly thought Chris was done with games," ex-Origin colleague Warren Spector told me, "He became a movie guy a long time ago, something he told me was one of his ambitions pretty much the day I first met him. But if he was going to make a game, he wouldn’t bother unless it was ambitious. Like all Origin alumni the appeal of the impossible is part of Chris’s make-up."

Roberts wanted to make a game, but this time around, he didn't want to go through the regular publisher route. "I think he saw publishers as an annoyance," Spector says, "the way you or I might find a mosquito annoying."

"As long as you don't get bent out of shape that not everyone loves all of your ideas, then you're okay. You're never going to get that, it's impossible. I can't get six people to agree on where to go to lunch, so how am I going to get 500,000 people to agree on exactly how the flight model needs to be? It ain't going to happen. Especially on the internet." - Chris Roberts

While discussions were held with the big companies and another Wing Commander sequel with EA was touted for a time, ultimately Roberts decided on a crowdfunding venture, and it paid off in a big way. Star Citizen's campaign has thus far raised $52.7 million direct from the players as of September 6. Financially secure and freed creatively, Roberts smiles broadly when he talks about the project: "I'm enjoying it because I feel like I'm getting to make the game I've dreamed of making with pretty much no compromise.

"I guarantee you I would not be in that situation if I was doing it for a publisher. There would definitely be compromises. I would say from Wing Commander IV onwards everything had some level of compromise."

But why, after so long out of the picture, did he decide to return to games? "Part of the biggest reason I'm doing this," Roberts explains, "Was feeling like I wanted to play this kind of game and they weren't getting made-so I was going to make one, basically. I was missing that experience."

To make sure 'that experience' was the same as it had been before, Roberts employed his younger brother and common collaborator Erin, which Chris described as "like having shorthand in your communication". But it wasn't to be exactly like the old days, for one big reason-Star Citizen is being developed very publicly: "We're literally giving people the game when it hasn't been tested very much," he explained, "We know there are problems, but we want to hear their feedback."

Of course with feedback comes... shall I say 'negativity'. Roberts chuckles when I bring it up: "As long as you don't get bent out of shape that not everyone loves all of your ideas, then you're okay," he says, "You're never going to get that, it's impossible. I can't get six people to agree on where to go to lunch, so how am I going to get 500,000 people to agree on exactly how the flight model needs to be? It ain't going to happen. Especially on the internet."

But Roberts does understand where at least some of the criticism comes from: "It's incredibly ambitious. It's not just a standard space sim. It's sort of four games rolled into one: the traditional space sim, the first-person action down on the planets, the full economy and trading sim part of it, and then it's got the big Wing Commander-style single-player story. We're basically trying to build four triple-A games at once."

Back to the money though-because with all that comes criticism from the online sphere. Roberts has been accused by some of taking fat salaries for him and his friends, rather than pumping the cash into Star Citizen. Bunkum, says Roberts: "We've got about 270 people working on this game, and they're not all in China in a sweatshop. They're [in the US], in the UK, all around the place [at three internal and two external studios]. You can just go to the game developer's salary survey, do the math, add in some overheads, and you can figure out it's a decent amount of money that we're spending, but only because we seem to be bringing in enough to justify it."

Besides, Roberts says he's not in it for the money. 'Some' would be nice, but as he says: "I'm not going 'I need a desert island' or 'I need a Bugatti Veyron' or something. I do see a few comments occasionally on articles saying, 'He's putting it all towards his gold-plated Bugatti Veyron'. Not really. The whole point of a Veyron is to go fast, and they've gone out of their way to make sure it's got the lightest materials possible. You probably don't want to put gold on it."

But what makes me, personally, confident that Star Citizen will deliver is the fact that the man at the helm, the Mancunian by way of California, gets feedback like this from game development legend Richard Garriott: "Chris is a rare, truly brilliant game designer. I was always shocked to hear his first pitches for a new game. While myself and others would labor to reach a good idea, and then need large amounts of time to refine it, Chris would often show up with a game design far more clear and powerful than I have experienced with anyone else before or since. The clarity and power of his ideas means that Chris also attracts strong talents to be around him. This works as a virtuous feedback cycle, helping to keep his creations and his teams top notch."

That's pretty glowing. But Star Citizen could still fail-and I had to know, what would Roberts do if the game tanked? He explains this isn't a concern-it isn't something he thinks about and he stubbornly persists to make it everything it can be, to make it the game he has in his head.

But, after a short pause, Roberts does consider failure: "The risk of failure is the public support ends before I can get it to the point where everyone thinks it's great," he tells me, "I'd rather not think about it though. It's like asking what happens if you walk out the door tomorrow and get hit by a bus.

"It would suck."