The Rise of Nintendo's Curiously Divisive Competitive Communities

Why do the competitive communities of Pokémon and Smash Bros. engender so much loyalty... and so much controversy?

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

We first published this piece in 2014. With a new Smash Bros. on the way for the Switch, we're republishing it here. Enjoy!

On a chilly Ohio day in 2006, three Super Smash Bros. Melee fans piled into a van with a rusted out bed and no backseats and set course for Champaign, Illinois with three CRT televisions. Their destination: Show Me Your Moves 6, now one of the largest semiannual Super Smash Bros. tournaments in the country.

The little group of Ohio State students, which included future Smashboards owner Chris "AlphaZealot" Brown, were part of a then-small but growing underground community of fans holding Smash Bros. tournaments around the country. Having met on campus, Brown and his compatriots, who went by the handles Soap and Paradigm, decided to drive hours to Illinois to see the scene firsthand. Being college students, the van they used lacked even basic amenities like a driver side window, forcing them to endure temperatures in the teens with no heat and the wind blasting in their face at 70 miles per hour. When they finally arrived in Illinois, they stayed at a house owned by the tournament organizer's house, where they slept on the floor with thirty or more other Smash Bros. fans.

Brown, of course, remembers the trip fondly: "Though our accommodations, transport, and even the tournament itself were less than perfect, I never once heard a single complaint. We were housed out of great generosity by other Smashers and their families based on a community bond. While the van ride to the tournament was freezing, we were mostly smiling and enjoying the absurdity of the situation.

Like all tournaments, even today, we brought the setups across state lines that were needed to help run the tournament. And like most tournaments, even today, the event was run by a small group of Smashers based simply on their passion for the game and the community. We supported the tournament and the community and in turn the community supported us, as best it could."

Today, the Smash Bros. community is larger than ever, having finally found some measure of legitimacy at events like EVO, though underground tournaments like Show Me Your Moves are still comparatively common. The same can be said for the Pokémon community, which has also been shunned before gaining wider acceptance over time.

Many competitive communities have started under similar circumstances, building themselves up bit by bit through grassroots initiatives and Internet message boards, but these communities seem to engender more passion than normal among their devotees. Perhaps because Nintendo games are such an unlikely foundation for hardcore competitive play, there's an "us against the world" undercurrent to their discourse that is less apparent in, say, the Call of Duty or League of Legends community. Rather than being bitter, though, the Pokémon and Smash Bros. communities have only worked harder, in the process forging tight knit bonds that in some cases have lasted years.

"No one could touch him

At first blush, the very notion of a competitive community based on a Nintendo game seems almost like a contradiction in terms. Going back to the earliest days of the NES, Nintendo has built its foundation on accessible and family-friendly games-a far cry from much more intense competitive fare such as Counterstrike or even Street Fighter II.

One reason Nintendo games have endured as long as they have, however, is their depth, which goes all the way back to the days of Donkey Kong, which was easy to grasp but notoriously difficult in its day. Because they're noted for their accessbility, though, Nintendo games tend to get short shrift among competitive gamers. Even Brown never really thought about taking Super Smash Bros. seriously until years after he first picked it up on the Nintendo 64. "I was introduced to Smashboards by a friend back in 2003-though to be frank, he really introduced me to the competitive community by routinely beating me with techniques I had never seen before," he remembers. "I am very competitive and really do not enjoy losing-when I was getting beat I kept trying to find out what I was doing wrong and where I could improve. Smashboards naturally was and still is the center of all information about Smash and is always the first place to find information. Using the site I was able to learn, improve, and eventually match my friend in battle."

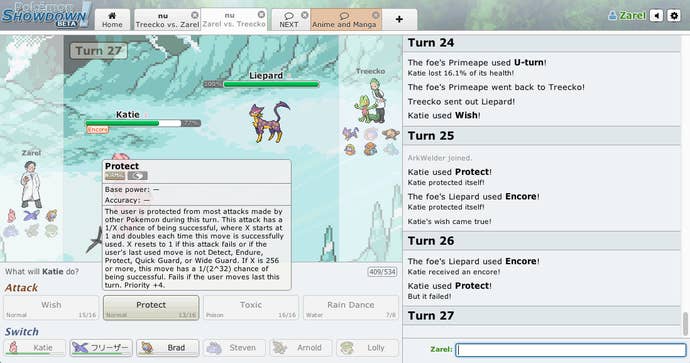

Brown's story is fairly common among Pokémon and Smash Bros. enthusiasts. Most get their start playing their preferred game at a very young age, only discovering the competitive community much later. Guangcong Luo, a programmer who recently graduated from the University of Minnesota, found the Pokémon competitive community only about four years ago, after which he began work on Showdown-a web-based battle simulator. Its turn-based format was partly what drew him in, "The biggest competitive games I can think of right now are games like League of Legends and StarCraft II, which are games in which click-speed and reflexes are very important. I don't see anything wrong with that, but it's nice to see representation from a game where players take turns thinking through moves. The only other turn-based competitive games I can think of are card games like Magic: the Gathering and Hearthstone, or board games like chess."

Luo launched Pokémon Showdown in October 2011, making it an alternative to existing battle simulators that had not yet adopted to the changes introduced in Pokémon Black 2/White 2, and it has mostly grown ever since. "Showdown's growth has always been slow and steady, other than one burst up to a thousand users at a time when we made it to the front page of Reddit. These days, we get ten thousand users at a time, and it's weird to think making it back to the front page of Reddit would barely even change the number of users we have."

Online simulators, of course, have been the lifeblood of the Pokémon community for a long time now. Originally developed as a way for far-flung battlers to test their mettle against one another, online simulators have mostly stuck around even with online-enabled Pokémon games arriving in 2007 due to their ease of use and customizability. Where Smash Bros. fans have typically congregated in towns like Champaign for local tournaments, Pokémon fans have long gathered on web-based apps like The Pokémon Battle Simulator and RSBot-a tradition that remains a part of the fabric of the community.

Online simulators and local tournaments provided a venue for both communities to grow and evolve, and soon enough legendary players began coming on the scene and winning tournaments, introducing new strategies, and making everyone else better. Brown remembers playing against one such legend-a player using the name Azen, who was prominent in the community around 2004, and the experience gave him a new perspective on just how far ahead of the curve high level players really were.

"Azen dominated me," Brown says blunty. "First, with top tier characters like Marth, Fox, or Sheik. Then he started winning using middle or low tier characters. This entire time, I stayed Peach, and after hours I hadn't come close to beating him. That was until he used Bowser. Peach has a massive advantage against Bowser and I leaned on this advantage to victory. I was so happy, I finally had my first win after hours of turmoil. For the next match, Azen did something he hadn't done the whole night. He chose Bowser, again. This was back in the day when we were still using five stocks for matches (now players use four stocks). That second match with Bowser was a massacre. He four-stocked me. It was not even close, which was when I realized Azen was just on an entirely different level. Without much care and without trying, he was better than 99 percent of Smashers. If he did care, if he was properly motivated, no one could touch him."

In the years that followed, Brown became a prominent member of the Smash Bros. communtiy himself, organizing tournaments and even purchasing the Smashboards site when its former owner, Major League Gaming, opted to move on. "I had done event contract and content work for MLG for about 7 years when the opportunity to acquire the site came around in 2012," he says. "Since they knew I was passionate about the game and heavily involved in the community, they felt the site would be in good shape in my hands. I'd like to think that I've shown that to be true."

He needn't worry. Much like its Pokémon equivalent, Smogon, Smashboards is a thriving portal for the community with news, tournament listings and rankings run by a volunteer force of moderators numbering around 100. Says Brown, "Everyone volunteers their time to help because of their love of the game and community. My role is mostly looking at the macro vision for the site including what projects to take on, general design of the site, and where to dedicate resources. More recently, I've been working on supporting tournament organizers and streamers to help grow the Smash scene overall. For example, the upcoming tournament 'The Big House 4' received help from Smashboards, including a $500 'Good Player Fund' to get strong players like Armada to the tournament who otherwise may not have been able to attend."

Both communities have mostly thrived through most of the 2000s and beyond, steadily expanding their scope to include more ambitious projects like Smogon's competitive Pokedex. What they didn't reckon with, though, was the backlash that followed their increased profile in the gaming community.

The Backlash

Masahiro Sakurai never seemed altogether comfortable with Melee's popularity among hardcore competitive gamers. In a 2010 interview with Famitsu (originally translated by 1UP, though the site is no longer online), Sakurai admitted that he had originally created Smash Bros. as his response to "how hardcore-exclusive the fighting game genre had become over the years."

"There are three Smash Bros. games out now. But even if I ever had a chance at another one, I doubt we'll ever see one that's as geared toward hardcore gamers as Melee was," Sakurai said at at the time. "Melee fans who played deep into the game without any problems might have trouble understanding this, but Melee was just too difficult."

Predictably, the competitive Smash Bros. community reacted to his comments with a sigh and a handful of multi-page forum threads. One fan responded, "I find that hard to swallow, considering that at the time I first picked up Melee I was completely casual about it. I was 10 when I first played it and to me it was the perfect casual experience at the time. I couldn't even imagine that there was a deeper side to it until a friend introduced me. So it's weird to me how he sees it as an obligation to keep Smash exclusive to a certain crowd, when one of the biggest things about Melee to me was its ability to be appealing to literally any crowd."

By that point, a large portion of the Smash Bros. competitive community had been at odds with Sakurai's vision for the series for years, having been deeply frustrated by many of the changes to Super Smash Bros. Brown remembers Brawl's launch as an exciting period that was soon tempered by just how different it was from Melee: "Brawl was not like Melee-the game played slower, had infuriating design decisions like tripping, and favored more defensive, though strategic, play. This left many players who preferred the pace and design of Melee frustrated. Some suggested the community abandon Brawl and go back to playing Melee, and some players did."

In the end, Brawl did have its own competitive presence, with more than 500 grassroots tournaments and some $250,000 in prizes the year after its launch. But the community was split. "Even to this day, there is the 'Brawl vs. Melee' debate that will crop up around the internet. When these debates occurred on Smashboards, they often spiraled out of control-things could get ugly," Brown says. "The entire topic was eventually banned as a discussion since no forward progress would be made on either side and it typically resulted in personal insults and negativity within the scene. The Brawl scene, and the Melee scene, essentially developed separately and were always held at different tournaments from 2009 onward-the lone exception being the largest regional and nationals tournaments where all Smash games were welcomed and the community could feel 'one' again."

In the meantime, a separate backlash was brewing among more casual fans of the series. In the years since the arrival of Super Smash Bros. Melee, the phrase "Final Destination, No Items" had become a kind of shorthand for expressing disgust at the competitive community's approach to the game. Some of it was to do with what more casual gamers felt was an overbearing sense of superiority lorded upon anyone who didn't feel like learning to wavedash-a physics exploit discovered in Melee that made it possible to slide along the ground without walking or running. But in other ways, it went deeper than that. If the backlash to the Smash Bros. competitive community could be summed up in one sentence, it would be, "You're playing it wrong."

Pokémon fans know this reaction well. It's the exclamation of disbelief that comes with someone wondering how anyone can get so wrapped up in what they perceive to be pure, dumb fun. This phenomenon is relatively unique to Nintendo games, having been precipitate by a "big tent" approach designed to bring in as many players as possible, as opposed to competitive games such as StarCraft II that have largely focused on narrower niches. Usually, it's a single aspect of the competitive scene that comes under fire, as in the case of EV training back in the days of Pokémon Ruby and Sapphire, which at the time was considered an "exploit" in the eyes of detractors for the way it leveraged relatively obscure mechanics. Either that, or non-competitive players complain about the attitude of the competitive community in general, which often comes off as brusque or elitist.

Even within the competitive communities themselves, things can be tense. Pokémon has lately seen a split among those who prefer the metagames introduced by Smogon, and those who prefer Nintendo's official rules. Earlier this year, Youtube user Verlisify brought matters to a head by releasing a video slamming Smogon's rules. The video has since been deleted, but reaction was nevertheless swift.

"The video was full of incorrect claims, including getting wrong what the VGC rules actually were, and so was widely denounced both by competitive Smogon players as well as competitive VGC players," Luo says. "But the reason the video became so popular that so many competitive players felt the need to denounce it was because discontent about Smogon rules is so common. Pokémon is a game with very broad appeal, that people enjoy playing for many different reasons, but the unfortunate consequence is that a lot of people feel the need to hate on each other for not enjoying their game the same way. I consider Smogon rules overall a very good achievement. They took a game mode that Nintendo doesn't really care to balance, and built their own ruleset around it, which is currently the most popular ruleset by a long shot."

Nevertheless, Smogon remains controversial among competitive and non-competitive battlers alike, with many complaining that the site has styled itself the ultimate arbiter of the competitive scene.

As overwhelming as the Pokémon community drama can be at times, though, Super Smash Bros. has arguably had it even worse. Since becoming prominent in the early 2000s, the Smash Bros. competitive community has been trapped between those who reject competitive play entirely, and those who don't think it's nearly hardcore enough. The fighting game community in particular famously rejected Super Smash Bros. out of hand for many years, deriding it as a "kids game."

"The discussion whenever Smash was brought up on fighting game forums would always turn hostile toward the game and it's players. As a result of this rejection, Smash developed entirely on its own and Smashboards grew as the home of the community instead of more traditional fighting game sites," Brown remembers. "In many ways this caused Smash to grow larger and much stronger than nearly all other fighting games. The tournament community had no developer support, no support from the traditional fighting game community, and was even reviled by casual players of the game. Aside from periodic help from Major League Gaming, the community was forced to develop a resilient mentality that it would only succeed on its own."

After several years of being belittled by the fighting game community, the Smash Bros. scene grew large enough that it could no longer be ignored, and the game was finally allowed into EVO, where Brown says it was the second most attended game that year. The next year, though, was a disaster: "Smashers transitioned to Brawl in 2008 and EVO ran with Brawl that summer. But EVO 2008 was announced to be run with items on. This was essentially blasphemy to the competitive community and the tournament flopped. Blame was usually put on Brawl players or on the game itself instead of this poor choice of rules."

Whoever was deserving of the blame, though, there was no denying that Super Smash Bros. had been given an opportunity to make its mark with the fighting game community... and failed. Smash Bros. would not be back at EVO after that.

... At least not for a few more years.

Smasher for Life

Troubled as Super Smash Bros. was at EVO, things have changed quite a bit since 2008. The rapid growth of eSports, among other things, have forced developers to recalibrate their stance toward competitive communities. Game Freak and The Pokémon Company, formerly somewhat cagey regarding their stance on competitive Pokémon, began organizing the Pokémon Video Games Championship in 2009, and have since largely embraced the hardcore element of their fandom. They've even acknowledged EV Training through Pokémon X and Y's Super Training mode, which significantly streamlines the process.

"It's definitely had an influence on the games. For example, X and Y just had their first world championship back in August, and we're always watching how the players are playing the games, of course," Game Freak's Junichi Masuda told us in a recent interview. "At this most recently Worlds, a big surprise for a lot of people was that Pachirisu was used in a really creative way, which was a big surprise to us as well. It was awesome."

If the Pokémon competitive community is occasionally frustrated with Game Freak, Luo says, it's mostly due to balance issues. "I think that for Pokémon, as a Nintendo game like Smash Bros, competitive balance is only one of many priorities in development, which is something that often frustrates competitive players. That's why things like Project M (for Smash Bros) or Smogon (for Pokémon) spring up. They've also signaled very clearly that 4v4 doubles is the primary balance target, and is the format that their tournaments are built around. Since the games themselves are mostly played in 6v6 singles, there's a lot of demand for competitive 6v6 singles battles which is neglected."

Still, Game Freak is definitely paying attention, which counts as positive progress for the community. And in recent years, attitudes have turned around a bit on competitive Smash Bros. as well, with the latest version on the Nintendo 3DS even bowing to the community and introducing a "For Glory" mode that automatically removes items and makes every stage flat. Sakurai still stresses that he wants to target the experience "at the center" and not a "very small, passionate group of sort of maniac players," but he says he also appreciates high level competitive play. He even has some experience with it himself. "Personally, I have a lot of experience playing in the arcade scene, and personally came out as a champion of a 100-person battle in arcade Street Fighter II," he told Kotaku proudly in a 2013 interview, though he admits it was a "long, long time ago." Even the fighting game community has buried the hatchet somewhat, allowing Super Smash Bros. Melee back into EVO in 2013, and affording Smash Bros. regular coverage on the community's flagship site Shoryuken. The warmer relationship has much to do with business interests, Brown says, as well as being "older and wiser."

"Large Smash tournaments will sometimes hold FGC games like Street Fighter in order to bring more bodies into the space and help cover the cost of the venue or in some cases make the organizer a decent profit," Brown explains. "The largest of tournaments like EVO stand to bring in a huge amount of revenue and additional exposure by adding the Smash community to their events. As such, it is in both communities best interest, at least at the top level, to respect and at least tolerate each other."

Issues still persist, of course. According to Brown, some organizers in the fighting game community continue to advocate for using items due to their belief that the game should be played on default settings as the developers intended, which is anathema to the Smash Bros. community. And there's still a bit of tension as well. "Older players have essentially settled past differences and are more accepting, but younger players or players with less maturity, on both sides, still throw insults or otherwise create a harmful environment." Brown says. "In the end, the scenes share a lot of similarities and shared experiences. We'll see how things develop in the next year or so with a new game on the horizon. For Melee, due to the sheer age of the game, it has mostly found it's place and is accepted, but each new Smash game will bring new challenges."

With both communities having now gained a measure of legitimacy, it's fair to say that both have exited their formative stages and hit something akin to critical mass. What's particularly striking is the intense loyalty the communities tend to engender among their hardcore members, which is really only rivaled by the fighting game community at large. Though there's certainly been plenty of turnover, many community members have been playing their respective games for more than a decade now, bringing with them a wealth of knowledge, experience, and ultimately, wisdom.

In the meantime, the relationships forged battling monsters and riding to tournaments in decrepit, freezing vans last a lifetime. When Brown talks about what keeps him coming back to Super Smash Bros., his love for both the series and the community are obvious.

"When Smash is plugged in, regardless of which version it is, I forget about what time it is and can get lost in playing the game for hours. Probably days if I didn't need to eat or sleep. At it's core the series is about freedom of expression, figuring out your opponent, and having fun as you exchange jabs in battle," he says. "No two matches are alike and rarely are any two exchanges in a match exactly the same. You are constantly learning, adapting, and changing based on both your history playing the game, and your history against a specific opponent. Throw all of the fun of the game in with one of the strongest, closest, and most inviting community of gamers, and you have something that few have been able to walk away from."

"Once you're a Smasher, you're a Smasher for life."