The Play's the Thing

Smarter writing in games is a good thing, but let's not forget the importance of intelligent systems, says Eurogamer's Chris Schilling.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

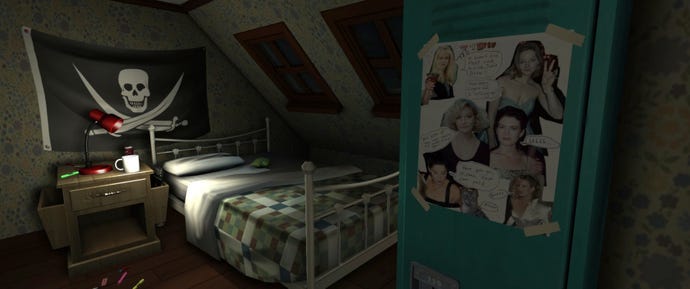

Gone Home is a critic's dream game. I liked it a little more than Eurogamer's reviewer Oli Welsh did, a little less than most other reviewers, but whatever you think of it, there's plenty of thematic meat to chew on, some brilliant writing, and a particularly progressive bit of character development (which shouldn't really be considered progressive but, in terms of video games, it absolutely is).

More importantly, it's over in two hours. You can get a review and a couple of features out of that, easy, with a total time investment far less than for that 6/10 action game you trudged through for 20-odd hours a couple of months back.

I tend not to read articles about games I know I'm going to write about myself until after I've said my piece, so this week I've been catching up with what others have been saying about Gone Home. It seems to have struck a chord with many, and I'm delighted about that. I'm far less comfortable, however, with claims that this is "the future of games" -- partly because it's a continuation of a trend I think is actually quite harmful.

This isn't Gone Home's fault. It is, like Dear Esther, an experiment in interactive narrative, and for my money, a more successful one. I'm not entirely enamored with its approach to storytelling, as good as the writing is, because to me it's structured like a bad movie, where the protagonist stumbles around awkwardly before triggering the next piece of exposition that advances the plot. But it's hardly unique in that regard: that kind of delivery is used in plenty of games. The difference is that Gone Home is being cited as a step forward simply because the quality of the writing and the environmental storytelling is superior.

Games like Dear Esther and Gone Home aren't so much confronting the issue of ludonarrative dissonance as sidestepping it entirely.

It all goes back to 'ludonarrative dissonance,' that wanky but admittedly useful term that describes the moments where systems and story lock antlers like testosterone-fuelled stags before finally separating, ragged and scarred by the experience. What I find interesting about the increasing use of this term in games criticism is that it's always the game that should change, never the story.

Sure, I've been guilty of pointing out the homicidal qualities of Nathan Drake, and at times during BioShock Infinite I wanted the shooting to be over so I could get to the next bit of plot. Ken Levine's response to the questions about Infinite's combat was pretty much a what-can-you-do? shrug of the shoulders, and I admire his honesty about the difficulties in marrying an intelligent narrative to fun gameplay. (Incidentally, I'm not convinced Infinite is as dissonant as some have made out. It's a jailbreak, essentially; how many non-violent jailbreaks have you seen?)

I'm not saying Infinite couldn't have done with a little more conversation, a little less action. But isn't it slightly troubling that critics are often found encouraging developers to change the parts of games that might make them more entertaining for the many players who don't give two hoots for a game's story? Do most gamers care about a developer's creative vision? I'm not convinced. One of the most common complaints I see about modern games is that you can't skip cutscenes.

If you ask me, games like Dear Esther and Gone Home aren't so much confronting the issue of ludonarrative dissonance as sidestepping it entirely. There's nothing wrong with that approach; some of my favorite games have relatively limited interactivity -- Hotel Dusk and the Ace Attorney series, for example -- and it doesn't make any of these titles less of a game. Games with great stories are a good thing, and the interactive medium gives us a more tangible connection to those stories. The narrative becomes richer for our direct engagement with it.

It does, however, annoy me when people say Gone Home gives them hope for the future of games, or that it demonstrates a maturity that's otherwise alien to the medium. Just as it annoyed me when people were saying The Last of Us was gaming's "Citizen Kane moment" simply because its cutscenes are uncommonly well-written and nicely performed.

Citizen Kane was a landmark moment in cinema because it was in love with the possibilities of the medium. When some critics talk about ludonarrative dissonance, it's almost with a sense of embarrassment that games sometimes have to be games. Gone Home isn't the future of games, it's a future; just one possible route that developers could take. It's an example of the malleability of this wonderful medium: it could start a trend, or lead a movement even, towards narrative-focused games with intelligent writing and mature storylines. But why does it seem like we're asking every other game to follow suit?

The reason, of course, is our desire for cultural acceptance. "Look!" we cry. "Games are smart, and mature, and emotional. Games matter." And the examples we always cite are the Heavy Rains, the LA Noires, the Dear Esthers, the Gone Homes; the games that prioritize stories over systems. Why? Because it's easier. Because it's easier to show a friend or a loved one that LA Noire features that guy from Mad Men and thus validates the idea that games are culturally relevant.

It's far harder to explain the joy of a perfect, arcing drift in OutRun; the exquisite hit-pauses of Bayonetta; the tangible solidity of Mario's worlds; the immaculate pacing of Resident Evil 4; the genius of Spelunky's universal systems. Imagine being part of the team that designed Portal 2's devious, mind-warping puzzles, only for everyone to bang on about Stephen Merchant's performance as Wheatley.

To me, a sign of gaming's maturity as a medium isn't that it can tell a story as well as a film, a play or a book, but that we can embrace everything it does well without worrying about its cultural relevance. And that means it's our job as critics, and as gamers, to try harder.

Let's not just focus our attention on the games that tell good stories, but also champion those that work hard to weave interesting mechanics with compelling narratives -- games like Brothers or Year Walk. Let's not chastise games for having the temerity not to prioritize narrative above all else. Sure, it's great if we can marry the two, but if a game's systems are really fun, who cares if the story isn't up to much? (As long as you can skip the cutscenes, obviously.)

In the course of writing this, I found an unlikely ally. At a DICE event in Las Vegas back in February last year, David Jaffe spoke out about developers favouring story over gameplay. An over-emphasis on story, he claimed, "is a bad idea, waste of resources, of time and money and worst, has stuffed the progress of video games, to our own peril." I don't entirely agree with Jaffe's assertion that games have "historically, continually been the worst medium to express philosophy, story and narrative" -- there may be some truth in it, but why shouldn't we challenge that notion? -- but I do think he's got a very good point when he says "we've let the gameplay muscle atrophy."

Gone Home is as valid an expression of the interactive medium as, say, Saints Row 4. But therein lies my point. Gone Home isn't the better of those games simply because it deals with more adult themes or has superior writing; indeed, I could make a case for Volition's game being the smarter, the more mature of the two. Rather, I'm saying we should embrace examples of great game design every bit as tightly as we do great writing. Let's talk about intelligent storytelling and intelligent systems.

In other words, let's celebrate games that are brilliant at what they do -- however they choose to express themselves.