The Oral History of Treyarch's Spider-Man 2: One of the Best Superhero Games Ever

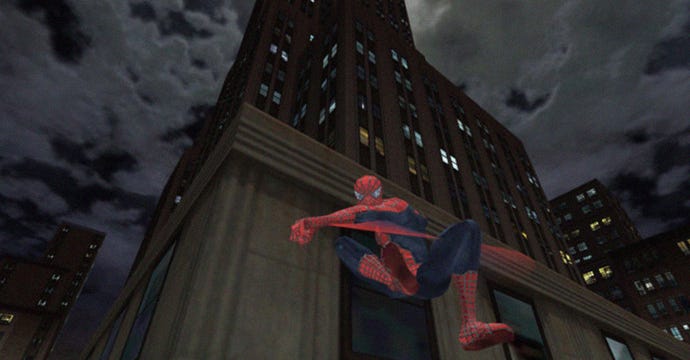

Sure, it made a lot of money. But it also rewrote the rules for what a superhero game could be. Here’s the story behind Treyarch's 2004 masterpiece.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

Originally, our Spider-Man 2 oral history was published on August 29, 2018. We've republished it honor of Marvel's Spider-Man's release today.

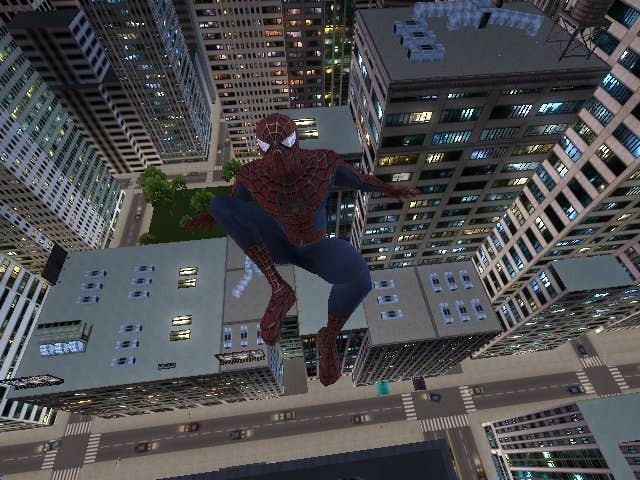

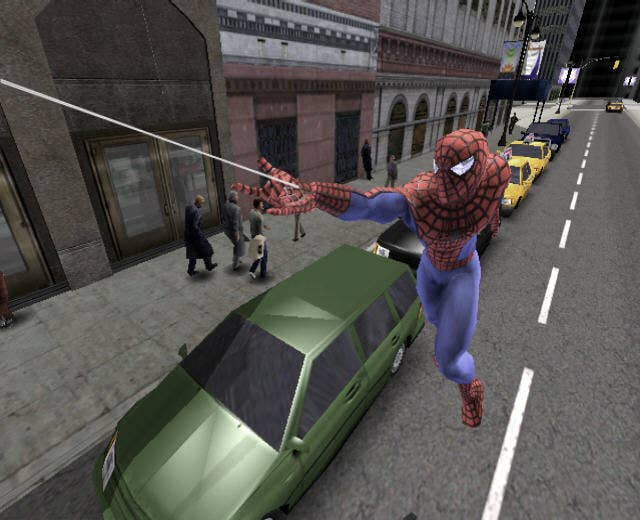

Tobey Maguire's voice-over sets the stage: "This is the city I protect. New York City. It’s my home, my playground, my responsibility." It took the Spidey crew at Treyarch two years to build that playground, spinning together every wacky comic book notion and technological breakthrough they could muster. But somehow they pulled it off—a colossal virtual Manhattan in which players could pick up a controller and experience a day in the life of Peter Parker.

These days, Treyarch is best known for the wildly popular Call of Duty: Black Ops series and the Zombies mode introduced in its 2008 blockbuster, World at War. But the Santa Monica studio had its beginnings in a condo in Los Angeles, where a group of college buddies first holed up to create Die by the Sword, a fantasy action game that drew the attention of the largest publishers in the industry.

Three weeks after 9/11, while a team of animators, artists, designers, and programmers were hard at work on the video game adaptation of Sam Raimi’s first Spider-Man film, Activision announced it was acquiring the developer for $20 million. Bolstered by the hype surrounding the movie, the 2002 Spider-Man game found massive success, with the PS2 edition becoming the seventh-best-selling title of the year in the U.S.

With a major hit on its hands, Treyarch’s core Spider-Man team immediately went to work on a follow-up in anticipation of Raimi’s 2004 sequel. Meanwhile, some of the studio’s best talent moved down the hallway to help with the adaptation of Steven Spielberg’s Minority Report, a game that proved even the company’s biggest failures were often dazzlingly inventive.

Inspired by the vast urban sandbox of Rockstar’s Grand Theft Auto 3, the team hit on an idea that would change licensed games forever: Give players an entire open-world New York. Let them choose whether to swing around and explore, take off the costume and deliver pizzas for Mr. Aziz, or even rescue the city from Doc Ock and that fleet of UFOs. Make them feel like a superhero.

This is the story of Treyarch's Spider-Man 2.

I. Bitten

Spider-Man (2002) was neither the studio’s first licensed project nor its first time working with a big publisher like Activision. Treyarch had done some run-of-the-mill sports titles for EA and Midway, as well as a port of Neversoft’s Spider-Man game, and had wowed critics with the Dreamcast version of Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater 2.

Tomo Moriwaki, creative director, Treyarch: I started towards the end of summer ’97. Treyarch was a very different company back then. It had a pretty conventional pack of dudes. We were all in our early-to-mid-twenties; there were about nine or ten of us. Lots of smart, nerdy kids, basically. I’d say that the culture was very much like a high-school advanced calculus class—just no girls.

James Zachary, chief animator, Treyarch: I worked at a company called Paradox. We did some Mattel stuff, and Marvel, and we did Rock-’em-Sock-’em Robots Arena. Old-school stuff.

Matt Rhoades, writer and designer, Treyarch: I worked for Interplay as a tester, and then I worked at Square as a tester. I worked as an editor at Square, as well.

Jamie Fristrom, technical director and designer, Treyarch: I worked on a bunch of RPGs for DOS at a company called Mindcraft, and did a Wheel of Fortune game, and a casino game for a company called Park Place. But it wasn’t until Treyarch that I started making cool games. [Laughs.]

James Zachary: I started off at a record label doing Quake mods and Unreal mods, and so the culture there was pretty crazy. We had a half-pipe in the studio, and we were doing sites for like Public Enemy, and we were doing sites for L7, and we had some connections to the Beastie Boys, so we’d see them come around every now and then. And the culture [at Treyarch] wasn’t that big of a change.

Jamie Fristrom: Treyarch got its start with Die by the Sword, and I was the second employee. It was all founded by college friends, so the only reason I got in there was because my two college friends, Pete [Akemann] and Do?an [Köslü], wanted to make a game company, and they wanted their friends to join on. I saw the game that they were working on, Die by the Sword, and I was like, “Wow, that’s cool. I want to be a part of that.”

Tomo Moriwaki: It was a PC game, it shipped in ’98, and it was notable in that it was a 3D action-adventure game of sorts, but there were no animators on the project. One of the founders was a guy named Pete Akemann. His dissertation was on some mathematical depiction of human movement, so he created this weird puppet-like system, and animations had to use that to create what looked like people animating. It was interesting; it was a really great first experience. Totally got me lost in possibilities. Crunch culture back then—we didn’t notice. We just worked all the time.

Jamie Fristrom: One thing that was really different was they just got a condo in Venice [in Los Angeles], and we slept there and worked there. We kind of worked in the living room and then slept downstairs. In a way, work was our life back then.

James Zachary: Everybody was kind of the same age, so it had kind of a college vibe to it. And, you know, we’re all double income, no kids, living in L.A. So it was actually a really good first experience in the industry. There was a lot of foosball, a lot of beer, a lot of hanging out 'til late at night. We’d hang out on the weekends as well. It was a good vibe.

Work was our life back then.

Jamie Fristrom: We were spending a lot of time at work and then playing a lot of an RTS called Kohan. I don’t know if you remember Kohan, but we played a crap-ton of that. It was our favorite RTS. That was our jam back then.

Tomo Moriwaki: Lots of 2 a.m. hijinks at the office.

Matt Rhoades: When you’re in QA, you’re a bit siloed. It’s not that you don’t get to interact with people, but you’re kind of off on your own. But I would say that one of the things that was really special about Treyarch, at least through Spider-Man 2, is that the core design team all really liked each other, and I think that there was a lot of mutual respect and a shared sense of purpose that you don’t always find. It was a really creative and very collaborative environment. And that, while maybe not unique in the industry, certainly was special.

Jamie Fristrom: I did ports to the Dreamcast. Not a lot of creativity on my part, there, but the Dreamcast versions were awesome. [Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater] ran around eighteen to twenty frames a second on the PlayStation, and had that weird non-perspective-correct texture mapping, so getting it on the Dreamcast was like, “Yay, it looks like a real game now.”

James Zachary: We did Max Steel, and we had these other little third-person, action-adventure-type games. I remember we did a couple of other demos—I don’t know if I'm allowed to say what they were. Demos that had big properties behind them. And it did just seem like one day we were like, "Hey, we're doing Spider-Man."

II. Pictures of Spider-Man

When Activision bought Treyarch in October 2001, the press release mentioned the developer was working on a Tony Hawk title for Xbox, a tie-in for “the forthcoming Tom Cruise film Minority Report,” and a PS2 game billed as Spider-Man: The Movie. Spider-Man ultimately launched on April 15, 2002, for GameCube, PlayStation 2, and Xbox.

Tomo Moriwaki: It kind of crept up on us. I think it started off as an opportunity to port the [2000] Neversoft Spider-Man game to PlayStation 2. We started in on development and figuring stuff out, and then, in the midst of that, it kind of transformed into a Spider-Man movie deal. Because that was all big news, and Activision signed its deal with Sony Columbia and got some number of games that it had some kind of right to. I think that’s also when Marvel signed the deal with Sony Columbia so that they’d have split rights to the Spider-Man franchise.

James Zachary: We didn’t even do a demo for it, whereas with these other properties we kind of mocked up some stuff. And I didn’t grow up a Spider-Man fan. I knew who he was, I had his comic books, and I definitely knew the story and the lore and Peter Parker, but I wasn’t like a hard-core Spider-Man fan.

Tomo Moriwaki: The Spider-Man 1 game was my first experience in a lead design position, and the team was still fairly new. There was probably not a single soul above the age of thirty. We still had attitudes about games, and were still bright-eyed and bushy-tailed. Definitely more than willing to bite off more than we could chew—mostly just being completely oblivious to that.

James Zachary: As soon as we got that property, it’s like you just kind of dive into it, and surround yourself with all those great characters and storylines, and it really helped. There’s a book called Drawing the Marvel Way by Stan Lee and John Buscema, and I grabbed a copy of that and just kind of transferred a lot of that 2D stuff they had illustrated there, and we really tried to nail that on the 3D side—trying to get some of those iconic poses and really pushing what you can do with the rigs and in the meshes. That book, in itself, probably was the cornerstone of all our animations.

Tomo Moriwaki: As a character, Spider-Man has so many physical capabilities in a 3D environment. One of the many ways that you could describe [the 2002 Spider-Man game] is “us just trying to keep up with Spider-Man.” And, in a lot of ways, it became us mimicking the Neversoft game whenever possible. We just tried to cope with and adapt to the movie script and fulfill our responsibilities. It was our first experience with a really big license client, and so I think, even though we might’ve had terrible attitudes, we kept our heads down and did the best we could.

We definitely had two parents. We had both Sony and Marvel to try to not p**s off. In that kind of a relationship, between Activision and Sony and Marvel, we were just like the kid that was playing on their iPad off to the side. Ultimately, as a dev, when it comes to those kinds of relationships, you’re kind of small bananas. You’re interesting if you have something cool to show; if you screw something up, you’re the snot-nosed kid to be blamed. But not a ton of direct communication. We’re not managing the brand, as the developer; we’re just dealing with the constraints of the deals that were established above us.

Matt Rhoades: [Spider-Man ’02] was my first design project, but I had been eating, breathing, living games for a long time, so it didn’t feel foreign to step into that role. It was largely just understanding the tools and then figuring out the dynamics of what was possible and what my responsibilities were, vis-à-vis other things. But I was hired, initially, primarily to adapt the script for the first movie. And I had some writing experience, some editorial experience, so I was happy to do that. And I have a lot of interest in narrative in games, and kind of how that works, but I always felt like I really wanted to be a designer, and so I used that opening to move into a design role. And, honestly, I feel like if you’re going to write games, you really ought to be embedded with the design team, because otherwise I think that there ends up being a disconnect between story and what’s actually happening in gameplay. And, ultimately, if there is that disconnect, it weakens the entire product.

James Zachary: Activision had the script, and we each had like two hours where we were locked in a room, and you couldn’t bring anything in there, so you had to read the script within the room. And then when we were done, we’d just start writing stuff. We’d leave the room and just start writing notes down, like, “Okay, we do this, this, this, and this.” And then when we saw the film, a lot of the stuff we’d read in the script, like the ending and so forth, wasn’t even in the film. It just changed. And luckily we didn’t follow the film to a tee, so we had some liberty there. But, yeah, that was interesting. That was my first experience of: “Oh, here’s how Hollywood works. Like, you’re locked in a room to read a script.”

Tomo Moriwaki: In my case, the role of creative director started off as basically being a supercharged lead game designer, because that’s the track that I came up in. And in the short term, it really meant a strengthening of the design department, which was very beneficial at the beginning of the project. Because so many things had to be designed, and we really needed to take the uncertainty of the things we were trying to pull off and set it into stone, and deploy just an ungodly amount of coder hours and animator hours to make it a reality.

It very quickly matured into a position where I am serving the team by coordinating the department leads. And certainly the buck might stop with me, and I have, theoretically, the highest amount of authority when it comes to making any decisions in terms of the content of the game—including the systems and the way the game works. Luckily, I had a very strong technical and systems-design background, so that allowed me to have easier communication with the code department and the design department. Culturally, I think I was very different from the artists, but at the very least I had eight years of art school—which, by the way, I never graduated from—to give me the necessary language to communicate with them.

Matt Rhoades: Design is obviously a critically important part of games, but at the same time there are things that the narrative demands that you [forgo]—no matter how great your design is. If your design is that Spider-Man has an AK-47 and runs around shooting people, well, you can’t do that.

Tomo Moriwaki: When it came to the designers, that was literally my soul. And when it came to the coders, especially over the course of Spider-Man 1, we became a really tight family.

Matt Rhoades: If narrative and design are on the same page, then it becomes a collaborative process where it’s not just the writer saying no, or the designers saying, “This is how it’s going to be.” It’s finding ways to use the limitations of narrative to actually make the game more fun and more interesting, and to deliver on whatever the fiction is that people want to be buying into when they pick up the game. And, with Spider-Man especially, he’s such a beloved character that you do want to make sure that you’re really respecting that, because that’s what is bringing a lot of people to the game. They’re gonna get to be Spider-Man, and if you aren’t true to that character, you’re gonna have problems.

Tomo Moriwaki: The transition to Spider-Man 2 is interesting, though, because we got a chance to see the [2002 Sam Raimi] movie before it came out, and that completely blew our minds. If someone wasn’t entirely a Spider-Man fan by the end of development on Spider-Man 1, when they walked out of the theater at that premiere, they were. That first movie was pretty awesome.

James Zachary: I was super nervous. I had a little taste from when I worked on a Marvel fighting game [called X-Men: Mutant Academy] of just how passionate the fans are. And we didn’t see any sort of animation tests for Spider-Man; we went off of the comic book. So I assumed there was gonna be some connection with the film, but I had no idea. Was he gonna be springy? Was he gonna be more stiff? Was he gonna be more realistic? Was he gonna be more cartoony? So, when I went in to see the movie, that’s what I was looking for, really. It was just like, All right, are we close to their animation style? And we actually were, which is funny, because we took some liberties. We made him kind of springy and bouncy, and they did the same. So that was a total relief.

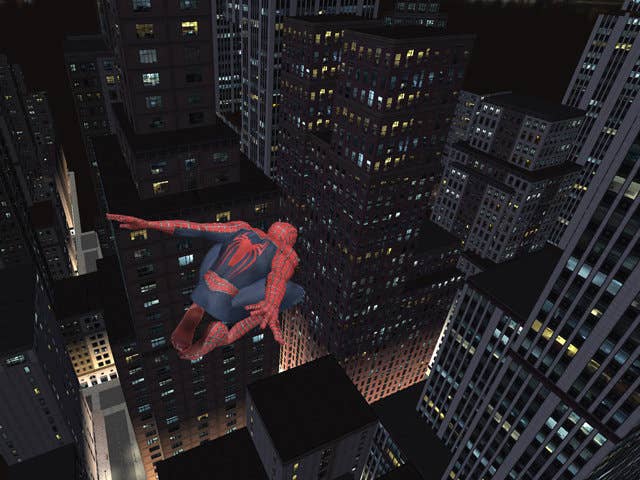

Tomo Moriwaki: I think that the Spider-Man movie really created an imagination of what it could feel like. It gave us an experiential target. And, at that point, everything transformed quite quickly. Now we knew where to go with it. Once that happened, it was pretty impressive. Spider-Man 2 had maybe twentyish people for the first six months, and during those six months we didn’t have access to the movie script. [Activision and Sony] were having their conversation, so we didn’t really have anything else to do but focus on the control experience, and everybody was dead set on that pendular, physics-based, realistic swinging experience. And that was probably some of the best development I’ve seen a pack of people do—at least being witness to it. It was all hands on deck between the animators, artists, modelers, all the designers. It was very cool.

III. Grand Theft Arachnid

A crude prototype, built midway through the first game’s development cycle, became the basis for Spider-Man 2. It grew out of common complaints about the Spidey games of the past, but Raimi’s 2002 film also gave Treyarch an extra dose of inspiration and a ready-made proof of concept.

Jamie Fristrom: Right before I started working on Spider-Man, I’d just finished the port for Tony Hawk 2, I think, and then I got married and had a honeymoon. When I got back from my honeymoon, work had started on Spider-Man [2002]. And it was sort of that—it’s practically flying, except it draws some cosmetic webs in the sky. And so it’s like, “Oh, that doesn’t feel like being Spider-Man.” Don’t ask me why, but the Neversoft Spider-Man before then, for the PlayStation, that felt a little more like Spider-Man to me. Even though, in that case, it’s just like a jumping platformer, again with cosmetic webs that shoot up to the sky. But I also really liked the stealth modes in the early levels of the Neversoft Spider-Man game.

So anyways, I came back and was like, “That’s not super cool.” And that’s when I went off and sort of locked myself in my office at night and started prototyping what I thought would be cool. But after a couple weeks of prototyping, it still wasn’t good enough, so when I showed it to the rest of the team, they’re like, “Okay, you know, we’re already several months in on Spider-Man with the system as it is, and we’ve built levels for it. We can’t just drop that and change horses midstream.” So we rode it out with Spider-Man 1, and then with Spider-Man 2 we gave it another shot.

James Zachary: We knew it was something when Jamie showed everybody for the first time. And he’s so nice, and he’s just like, “Hey, yeah, I kinda worked on something I want to show you guys.” And we’re like, “Holy s**t, dude, this is amazing.”

Matt Rhoades: I remember, after the film, Jamie and I are actually standing next to each other in the bathroom. And we had done what was, at the time, kind of what everyone imagined swinging looked like in Spider-Man. It was kind of derived from the 1960s cartoon, if you’ve ever seen that: the hand-over-hand, very level, boring swinging—the Tarzan-swinging-from-vine-to-vine kind of thing. And seeing the first film, that was when, I think for all of us, all of a sudden we kind of understood what Spider-Man swinging through a city would actually be, and what it would look like. And I remember having a conversation with Jamie in the bathroom, saying, “It’s so dynamic and it’s so cool. There’s gotta be some way—if only we could capture that in the game somehow.” And Jamie’s saying, “Yeah, you know, maybe there’s something that we can do there.”

Jamie Fristrom: Nobody remembers this except me, but I started working on those prototypes before that movie came out. For me, it was not, “Oh, that movie looks really cool. Let’s do that.” For me, it was more confirmation. It was like, “That was what I was trying to get at with those earlier prototypes.”

Matt Rhoades: But I think it was that first film that really kind of lit the fire under us and inspired us to want something more from the swinging than what we’d seen in Spider-Man games in the past, because it just looked like so much fun. What he was doing was this exhilarating, thrilling thing, as opposed to kind of walking through the air with webs attached.

Tomo Moriwaki: We were being bombarded all the way through the Neversoft game’s existence and our development process with the idea that the webs connecting to nothing in the sky was just a very common complaint. And so I think, as an organization, we had some sensitivity to that concern and an interest in trying to address it.

James Zachary: He showed that prototype—I can’t remember where we were in the development cycle, but we were getting close to the end—and I remember looking at that, and I was thinking two thoughts. Both of them were, Holy s**t. But one was, Holy s**t, we’re gonna have to not ship this game. Because this is so cool, we’re gonna have to switch everything around and try to get this in. Luckily, we had some really smart people on the team who said, “No, let’s hold off on this until Spider-Man 2, and we’ll tackle this then.” And I think that was a lifesaver, that decision.

Jamie Fristrom: One thing I think the movie version did show us, which was a pretty indispensable part of the Spider-Man 2 experience, was sort of the running along on the walls that he would do. It wasn’t just that he was a big pendulum going from wall to wall. He was doing some other dramatic stuff, sort of like it was an extreme sport for him, and that definitely informed Spider-Man 2 a lot. That was not in my earliest prototypes.

James Zachary: We actually had a very small team [of animators]. There were only like two or three of us cycling in and out. And we’re doing Spider-Man animations, and enemies, and cutscenes, and when I look back at it now, it kind of shows that we had a small team.

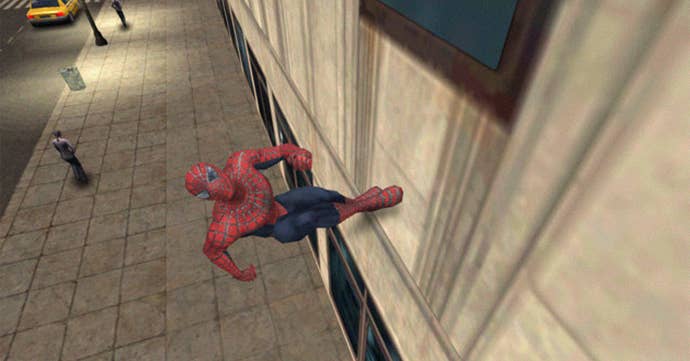

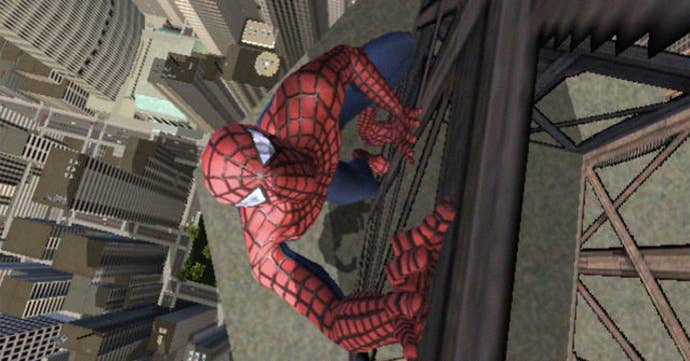

Jamie Fristrom: The crawling was kind of slow in our game. Like, if you tried to crawl from the bottom of the Empire State Building to the top, you’d be like, “What time is it?” But we had those wall runs, where you could start on the ground and run towards the wall and hold down—I think it was the circle button?—and you’d just run straight up the wall. I think Shinobi had already come out at that point, so Shinobi was an influence for that.

James Zachary: When we went to Spider-Man 2, our team did get a little bigger, but we also started doing a lot more procedural stuff, where we’re letting the game do a lot of the blends. The way the swing cycle worked—depending on where you were—if you think of a circle, and the center of the swing is in the middle, you’d swing in a complete circle from basically a zero being, like, where you’re down at the ground, and you’d just do a ring. If you grabbed a pole and you just spun around it, basically each interval or each segment would have a pose that Spider-Man would blend to. So as he swung through the whole thing, he would kind of blend into different poses, which worked.

Tomo Moriwaki: The team rolled straight from Spider-Man 1 into Spider-Man 2. Obviously, the Spider-Man 1 experience dominated our thoughts. It was almost a hundred percent influential in affecting our choices for Spider-Man 2. Well, I’ll throw in GTA 3 as a twist to that.

Matt Rhoades: The first one was fairly traditional, and just kind of followed the model that Neversoft had established with their PlayStation Spider-Man game. It was the second one where we really sort of broke the mold a little bit. But I think there was a sense that we needed to explore the character, and we weren’t trying to do anything crazy. So as long as we were following the movie script in a way that the director and the studio were satisfied with, and not doing anything crazy with characters, they were largely leaving us to our own devices.

Tomo Moriwaki: We all got infected by that. I mentioned GTA 3—this idea of like an open world and a sandbox experience. That was dominating all of the designers’ thoughts, because we were playing that excessively. And this idea that we would play it and never really pursue the story. So those things started coming together to create a really strong motive, in Spider-Man 2, to break out of our bubble and get ourselves into trouble.

It actually really felt like you were Spider-Man.

Matt Rhoades: And when we started seeing those prototypes, initially, there was a lot of resistance to the idea of doing a streaming city. It was tech we didn’t have. It’s obviously very complicated to do that. Creating an open world was something—not only had we never done it, very few people had ever done it. So, with the initial swinging prototype, the idea was always that we were going to build kind of biggish zones, and we were going to have the swinging [take place] in there.

And the moment that we actually started seeing those prototypes, the thing that struck a lot of us was: We need the whole city. It’s so great to swing, and it’s so much fun, and it’s so cool. But you hit those zone boundaries, and it sucks. Having that sense of freedom, all of a sudden it’s just not good enough to hit an invisible wall and kind of get turned around. So those initial prototypes opened the way for us to see what kind of game it was we were really going to end up making.

Jamie Fristrom: It was definitely us ripping off Grand Theft Auto 3. We had a lot more verticality than they had. Grand Theft Auto 3, at the time, was pretty flat, and because it was flat, they could stream in districts as you arrived at them and you wouldn’t really be able to tell that they weren’t there before. So that was our big technical challenge. If you’re on the top of a skyscraper and you’re looking out across Manhattan, there should be something there. You shouldn’t just fog it out; you can’t just have nothing. So we had two levels of detail. We had the sort of hazy, blocky buildings in the distance, and then the detailed ones would load in up close.

Tomo Moriwaki: It was kind of our first thesis on what “open-world sandbox” meant, and the only extremely attractive example that was floating around was GTA 3. In a very crude sort of way, we’re like, “Oh. You can just do stuff. And you don’t have to do any of it, but it’s fun. And you have to be able to move around, you can explore, you can use the mechanics, and you can just do what you feel like. Oh, this is really interesting.”

It’s like, “Hey, look, we’ve got this character—” And almost the entire design staff was totally into fighting games. Really kind of a player-package, controller-heavy set of designers. So it just played right into our vulnerabilities. That line of thinking had a really big effect. And our design process was pretty sloppy back then. I don’t know how much high-level strategy we discussed about what this all meant. We did a lot of talking about, “We’re in for a lot of work.” We knew it was gonna be painful, and we just didn’t care.

Matt Rhoades: There are so many things about making an open-world game that we were really learning as we went. So much of it was trying things, and trying to get things to work. There was constantly this iterative kind of process going on. One of the things—and this is another discussion, actually, between me and Jamie—one of the things that we started realizing is that, when you’re swinging around, it’s really fun. But one of the things that I mentioned to him was, “If only there were more that you could do when you’re swinging.” You know, you’re in the air, you’re getting all this air when you disconnect from the web, but you’re just kind of flying for a little while, and it’s very—you lose engagement in those moments. And we kind of hit on the idea of having this sort of pseudo trick system.

James Zachary: That was a huge change. When I got into games, and when I played games as a kid, I always looked forward to the next level, because it was just so different, right? They would change the color palette; the shapes would change; the lighting would change. It was just a totally different experience, and so you always wanted to see, like, What’s that next level? When you go to an open-world game, you don’t have that. Especially back then—it’s changed a little bit, but back then you just couldn’t make those changes and have everything fit on the disc and have all the memory. So everything had this same kind of feel to it, and I was worried about having a game that looked the same from start to finish. That was one of my concerns.

Matt Rhoades: Since none of us had ever done it before, and none of us knew exactly—we knew kind of in broad strokes what the target was that we were aiming for. But we were finding our way as we went, and so there was a lot of room for these really kind of fun offhanded experiments that ended up in the game.

Things like the trick system. Even though it feels extraneous, it ends up actually binding the swinging system together in a pretty compelling way, and it links back into things like the spider-sense meter. It had a lot of hooks into our other systems that I think ended up making it pretty compelling, and then we added unlocks to it, so that you could do all of these different moves in the air, and it starts feeling a lot more like that dynamic swinging that you see in the films. If you let go of the web in midair, and start tapping the jump button, you’ll actually do flips and other kinds of moves in the air, and you can unlock additional ones as you go along.

James Zachary: I had memory concerns. Not like I can’t remember anything, but memory concerns of: “Okay, now that this is an open world, are we going to have to cut down on Spider-Man’s animations? Or do we have to cut down on his polycount, or his bones on the rig? And can we have as many hit reactions as we were hoping to have?” Those were some major worries going into it, but once we started working on it, we were actually able to do a lot with him and his animations, and all those concerns I had up front didn’t really end up being that big of a deal. We found solutions around ’em. But, yeah, for the most part it was—I don’t want to say “smooth sailing,” because there’s a lot of hurdles we had to go through—but it was just everything I expected that we’d have to tackle, and nothing really sidelined us too much.

Jamie Fristrom: It seemed like it was a war of inches. These days, I never spend that much time prototyping something. We—first me, and then we as a team—were sort of really gnawing away at that problem, trying to make it accessible. For the first prototype, we had like a demo level for Spider-Man 1. I forget who made it and what it was supposed to show, but I went through and I marked that level with little points that I thought would be cool to swing from, like the corners of buildings and stuff. So you didn’t have a whole lot of control in that early prototype, and also you would stick to the wall, because like in Spider-Man 1, when you jumped and hit a wall, you’d automatically stick to it and enter the wall-crawling mode.

So super not fun, because you can only swing from certain points, and then if you make a mistake and you accidentally brush against a wall, it just kills your momentum right then. Once I got good at it, and I thought it was fun, it was like, “Look, I’m swinging around, I have intention, I’m making Spider-Man do pretty much what I want him to do.” But for people picking it up for the first time, they’re like, “This is horrible. He’s doing unintuitive things, and then he sticks to a wall, and I’m stuck.”

James Zachary: I think we’re all used to running around, shooting stuff, and jumping around from platform to platform. But I think this was the first time where you actually felt like you were truly Spider-Man by swinging and having those attach points. I remember the first time I just jumped off of a building, and was just dropping to the ground, and people in the room were like, “Oh my god, wait.” Then when you hit the swing button, and you did that swing, it was just so exhilarating. It actually really felt like you were Spider-Man.

Jamie Fristrom: So, from there, the designers started adding more and more points to the level that you could swing from. [Senior designer] Eric Pavone was a driving force for that, just adding a ton of points to the level. It seemed like the more points he added, the more fun it got. And that’s when one of our programmers, Andrei Pokrovsky, did sort of a ray casting thing, where it’s like, “Okay, now it doesn’t matter how many points we have in there. You can just swing arbitrarily, from arbitrary geometry.” Which made life easier for designers too, because now they didn’t have to mark it up with little dots everywhere.

So that was a big leap forward in the prototype. And then making it so you don’t stick to the walls—you do a cool little animation when you hit a wall, or you run along the wall for a little bit—you look like a surfer or something. That was huge, partly because your momentum isn’t being killed, but partly because it does a cool, juicy feedback-y thing, and it’s like hitting a wall becomes fun now.

James Zachary: And I don’t know if it would have worked as well if it wasn’t Spider-Man, because you have all these images of the character—from when you were a kid, or if you look at comic books, or if you saw the movie—and you project a lot of that energy into the game. So when you hit that, your mind is telling you, “Oh my god, he’s doing exactly what he would do in the movie, or exactly what he did in the comic book.” And he may not have been; it may have been that he just swung with some sort of funny-looking pose, but having that free swinging really kind of stitched all that stuff together. All your internal learnings.

Jamie Fristrom: There were kind of two different fronts we were fighting the war on. There was making the swinging cool and fun, but there was also the open city, [and] different guys working on that part of the problem. And, yeah, after I had the first few prototypes and that was sort of on its way, I did step into more of an oversight role, just watching what everybody’s doing and keeping an eye on the schedule and hoping we’d have cool stuff to show when it came time to show it to upper management and say, “Hey, this is what we’ve got going on. Should we keep going this way, or should we pull the ripcord and reskin Spider-Man 1?”

Tomo Moriwaki: [Feedback from Activision] was usually positive, because when no one was looking, we were able to get the swinging experience to feel pretty damn good. At the end of those six months, there was this great maybe eight-work-day period where, in the span of those eight work days, we saw our producer for the first time in a long time. He saw the game and was blown away by being able to swing around New York City. And then he brought his boss in like twenty-four hours later, and then seventy-two hours after that, his boss came in. The next day after that, Ron Doornink, CEO of Activision at the time, was sitting behind me while I was playing the game. And he had a very policeman sort of vibe to him, with a kind of circus-strongman mustache, and he had his arms folded, and his face didn’t move at all until the end. At which point he said we were awesome, and then we all breathed a sigh of relief.

Jamie Fristrom: Activision was super nurturing. We were kind of surprised, because it’s still a hard game. A lot of people pick it up for the first time and they just can’t do it. And so I was always expecting Activision to sort of like come down on us and say, “Yeah, we focus-tested this, and people can’t play it. So, you know, do something simpler.”

You sort of see that happening to the Spider-Man games over time, right? With Web of Shadows, you can start swinging from the sky again, so you can just sort of cruise over Central Park. Man, I laughed so hard at Spider-Man: Homecoming. That scene where he’s in the park and he shoots his web into the sky, and nothing happens—it just really shines a spotlight on that. Have you ever seen the cartoons from the sixties? The ones where they invented that theme song that’s so prevalent? It’s cel animation, so it’s like, “Yeah, we’re using the same animation loop where he’s just swinging from nothing, and we just put it against a jungle or an alien planet, depending on what episode it was.”

IV. Webheads

As with many developers, the employees at Treyarch were divided into a handful of distinct teams, each working on a specific project. When 2002’s Spider-Man become one of the top-selling games of the year, those who’d worked on it made a huge profit, and those divisions became rivalries.

Tomo Moriwaki: We were purchased by Activision in the middle of development on Spider-Man 1, kind of shortly after 9/11. I remember that 9/11 caused quite a stock slump, and that became a part of the conversation between the companies, in terms of what the purchase value was.

Jamie Fristrom: Because the first one had done well, and so many Treyarch employees who worked on it had gotten sizable bonuses, people were pretty excited about what they might get, monetarily, with Spider-Man 2.

Tomo Moriwaki: We had the default Activision royalty scheme in place for the Spider-Man team, and when Spider-Man shipped, of course, the movie was a huge hit. Best Buy put spiderwebs over pamphlets in every single house in the damn country. So there was all this free advertising. I think there was a commercial for the game at the beginning of some of the movies. And that game sold a lot of units. I don’t know specifics, because back then everybody’s information seemed faulty, or whoever knew wouldn’t tell. But I know it was many millions of units across the three platforms. I also know that the royalties were pretty significant—a lot more money than I had seen in my life up until then. That changed a lot of people’s attitudes. Young people with a single big check—I don’t know if that’s always the best combination. Different people responded to it in different ways, and certainly some rivalries based on that started to emerge.

Jamie Fristrom: And sometimes it was even unfriendly. But, yeah, the Spider-Man team got these bonuses. From both royalties and the sort of agreed-upon bonus: “If the game does this well, you’ll get this much.” And the rest of the company didn’t get to see that. And it wasn’t because they were any less talented, or they worked less hard than us. They just had the bad luck of being assigned to the wrong project. So there was sort of that unfairness thing going on, and even if you try to be magnanimous about it, there’s gonna be a little bit of resentment there, right?

Tomo Moriwaki: There were also rivalries just because there were cultural separations between the Spider-Man team and the rest of the company. We had a lot of the people that had been around a long time—a lot of people that were there back when we were smaller. A lot less of a healthy attitude about how we should coexist with authority. Everybody was young, but we had more people who, if given no constraints, were likely to get fired because of their behavior. And I think that that was visible from the outside, so it kind of created some amount of: Who the hell are you guys? And, honestly, our answer would’ve been, “We really don’t know.”

James Zachary: I don’t recall that. Maybe it’s just that on the art side we had a really good, tight-knit group, but some of our animators that helped out on Spider-Man transferred over to Minority Report. So I don’t think there was like a big friction there.

Tomo Moriwaki: [Most of us] didn’t have a lot of involvement in the Minority Report game.

James Zachary: It actually was a nice break, going to Minority Report, and I just went over there because they really needed some help. And we’d just wrapped up [Spider-Man ’02]. All of our Spider-Man titles took a lot of work; we worked a lot of long hours. Crazy-long hours. So when they wrapped up—and this is what was nice about making games back then—when you’re done, you’re done. Once it went into the box, there wasn’t like downloadable content and you weren’t always like upgrading or updating it, which is the case now. When you were done back then, everyone just kind of fell down.

And so I had to get creatively recharged again, and I went over to Minority Report to help out a little bit with some of the animations and some of the combat design. And then, when Spider-Man 2 started to ramp up, I was ready and fresh and eager to get back into Spider-Man. It’s important that you have those breaks; I did Spider-Man for like ten years, and if you just do that one character that whole time, you start to lose it. So you need these little outlets where you can explore other characters, other storylines, other styles. Minority Report was kind of fun in that way.

Jamie Fristrom: I’m not a hundred percent on this, but I remember Minority Report being in a two-floor office in Santa Monica. We’d moved from El Segundo to Santa Monica to do this, and so the Minority Report people were just down the hall. But then downstairs we had people working on a snowboarding game that never shipped, and people were working on Tony Hawk for the Xbox. And we had one more team, but that didn’t come into play until halfway through Spider-Man 2, when we started spinning up the Ultimate Spider-Man team.

James Zachary: When they started doing Call of Duty [a few years later]—it was also James Bond—we had two floors in the building, and they were on the lower floor. The Spider-Man team was on the top floor, or the second floor, and we really didn’t even see those guys on the James Bond or Call of Duty stuff. It felt like they were just almost in a different building somewhere. And the Spider-Man team was also like the group that formed Treyarch; the first seventy-five people at Treyarch were all on Spider-Man. So I don’t know if there was a rivalry, but it was just that we didn’t know that team as well. And we grew fast. We grew really fast. I think I was employee number fifty, and within a couple months of that, after Spider-Man 1, there were like three hundred fifty people there, and I remember walking around going: “I don’t know any of these people.”

V. Nerds in Suits

When the Spidey devs commenced work on their 2004 sequel, they faced an interesting predicament: The game would feature full voice-over and gorgeous Blur Studio cutscenes, but they wouldn’t have access to the film’s shooting script for a while. And once they did, they saw how unfit the movie’s story was for a video game narrative. So Treyarch was free to come up with its own, drawing on every kooky idea they had about the character’s rich and colorful history.

Matt Rhoades: The first thing that happened [on Spider-Man 2] is that Tomo and I, and a couple of Activision folks, a couple of people from the studio—there were a handful of us that went to the Sony Pictures lot. And they obviously were very protective of the script, so we could only read it on-site. We didn’t have the ability to take anything other than our memories back.

James Zachary: I think that was key, because we had to have our own story for everything to work. If we’d tried to follow the film too much—there’s just too many creative changes that happen in the film as it goes through production. There’s no way we could follow it. So we were trying to kind of lay underneath the film, and just touch it in parts, so it felt authentic.

Matt Rhoades: But they let us read the script at the end. It was not the final script, but it was close, and they also let us read it as they made their changes. But we got that initial look at the script, and based on that I went back and did just a treatment—a layout of what the story might look like in our game. And we also had a list of villains for Marvel that we wanted to use.

James Zachary: Mysterio was fun, too, because he’s like totally crazy. We had some good fun with that character, as well as his fun house. Like, who doesn’t like to play a game in a fun house?

Jamie Fristrom: Do you remember the bit when you face Mysterio, after getting through the Mysterio level? You run into him in a convenience store, and then he does that sort of video game cliché thing, where his health bar fills up over and over again, and it’s like, “Oh, no, here’s the final boss.” And then you hit him with one punch and he goes down. That’s a classic moment for me. Matt Rhoades was the guy who came up with that, sort of subverting the boss-fight cliché.

Matt Rhoades: I love Mysterio. I mean, he’s a great character, and I’ll be the first to admit that I have what could generously be described as a quirky sense of humor. And I love superheroes, I love comic books—but you can love something and still be aware that it’s pretty silly. I was always keenly aware of how goofy a lot of these characters were. And especially when I started kind of writing the stories, I started looking at the origins of the characters. Not their modern incarnations, where they’ve tried to make them cooler and whatever, but their original 1960s Stan Lee–Steve Ditko origins. And the original origin story of Mysterio is that he was pretending to be an alien. He was a stunt man who was pretending to be an alien to discredit Spider-Man, somehow. And I just thought, He’s so goofy, and it’s so whimsical and fun. Is there a way to kind of incorporate that into the [Raimi] movie world?

The Sega CD Spider-Man game has some really fun, wacky Mysterio stuff in it. He drops you into a pinball machine, and you kind of play pinball in the middle of the game. He draws out these doppelgängers of Spider-Man. And I basically stole that and reused it. One of the missions that I did was the fun-house level where Mysterio drags you down into this death trap, this fun house. And we actually, at one point, had a bug in the game that was causing Spider-Man to get all crazy and distorted as he was swinging around. And I asked the programmer, “Hey, you know, obviously we need to fix this, but can you give me the ability to create these versions of the character, as well?”

And he did. So at one point we have all these fun-house mirror Spider-Men coming out of the mirrors and attacking you. It’s certainly, at the very least, an homage to the Sega CD Amazing Spider-Man game. But we wanted things to feel like they were expanding on the movie, and I wanted very much to pay homage to the classic comic-book [Spider-Man], which I think really was an inspiration for Sam Raimi, as well. I think a lot of what he was drawing on was the classic Spider-Man. Sam Raimi’s kind of quirky, and has an offbeat sense of humor too, so I think it works.

Tomo Moriwaki: Because it took so long before we could actually get access to the script, we had developed a bunch of contingency strategies, so we already had the structure of: “We’re gonna take their story, and find the most important milestones, and then we’re going to not have any of the rest of it, and we’re going to fit our stuff in between those milestones.” And that allowed us to start designing enemies and characters and environments in advance of having access to the script.

Matt Rhoades: With the licensing, especially in the pre–Marvel Studios days, they had really balkanized their character licenses. So there were characters that we would’ve loved to use that we couldn’t. There were characters that were in contention that were probably more trouble than they were worth. But we had a list of characters, and I wrote this initial treatment, and we talked about what villains we wanted, and I talked about what villains I thought would be interesting to have. From there, once we had the treatment and everyone was more or less happy with it, we started filling in what the individual missions would look like, and what the actual gameplay would be. Still fairly high-level, though.

Tomo Moriwaki: And, in the end, it was probably for the best, because the Spider-Man 2 movie is really tight and contained. It’s kind of an awful story for an open world. [Laughs.] It’s a great personal character exploration—a non-origin-story Spider-Man, freakin’ Doctor Octopus, Mary Jane.

Jamie Fristrom: One thing that was convenient was that we had a lot of time. It was unprecedented to have twenty months to do a project. And then the movie got pushed back, and we’re like, “Wow.” We had two years, altogether, and them pushing back the movie gave us the time to give it the extra features and polish we wanted to give it, so that was great.

James Zachary: Doc Ock was fun. We actually tried to have each of his four tentacles have its own personality, which we had high hopes for. I don’t know if it read that much when you were playing the game, but they may have added a little subliminal messaging. We had one that was more of a motherly figure, and one that was more of an aggressor.

Tomo Moriwaki: Doc Ock and—what was that actor? Alfred Molina? He was something else. Well, actually, Willem Dafoe from the movie before was also pretty amazing. When we did our voice-over recordings of them, it was really impressive to watch them in action.

Matt Rhoades: I did direct all the VO, as well, and picked the takes for all the characters. And I didn’t really understand what a luxury that was at the time; I just sort of took it for granted. It makes a huge difference, as the writer, to be able to say, “Well, this is actually what I was going for when I wrote this line.” Or, “This really isn’t working. Let’s change it.” And to be empowered to do that, as the actors were recording, was amazing. It was really nice to get to wear both of those hats.

Tomo Moriwaki: It was a pretty high-pressure environment. We were strapped for time; we were spending so much money on these hours. We just had this we-need-to-move-as-quickly-as-possible, but-if-we-hurry-we’ll-screw-everything-up kind of stress. I do remember that the voice actors who weren’t the leads were extremely impressive in their ability to just immediately switch into character and get us exactly what we wanted. The main actors—it was clear that they weren’t maybe always voice actors, for example. They took a little bit more work. Plus, we tired them the hell out. Because Tobey had two eight-hour days in a row, nonstop voice-over acting. Alfred Molina was really impressive. Kirsten Dunst. It was all very good. It’s just that the professional voice actors were like wizards, comparatively.

Matt Rhoades: All the actors that I worked with—both the film actors and the voice actors—were incredibly professional. And Tobey is, or at least was at the time, a huge video game fan. So he got what we were doing, and was very enthusiastic about it. I think the hard thing for him—[and] there were a couple things, but one of the hardest things was, he talks a lot in our game. And that’s my fault, because I was writing for the character of Spider-Man as I thought of him from the comics, rather than writing for Tobey Maguire as Spider-Man.

VI. Great Responsibility

A few months out from the game’s June 2004 release date, Treyarch began cutting environments, missions, and storylines in order to ship on schedule. This increased the amount of crunch time the team was putting in, and brought to light the unsustainability of the studio’s labor practices in those days.

Tomo Moriwaki: We had to throw away what might’ve been hundreds of man-months’ worth of work in this colossal underground recreation of—maybe almost like a third of the scope of the overland city. We had this super quirky, gigantic sewer system that was like a hamster maze of varying spaces that you could swing around in, and crawl around in. And some of the bosses were gonna be down there, and we had encounters down there. It was completely insane. And, probably in the last four months of development, it was clear that we had to cut it, and that was a sad day. That was a good learning experience for me: Time does pass, and eventually the game does have to come out.

Matt Rhoades: Several of the things that got cut I actually brought back as missions in Spider-Man 3. And that game is a whole sad tale on its own, but the Scorpion missions that are in Spider-Man 3 began life in Spider-Man 2, and the Kraven missions in Spider-Man 3 began life in Spider-Man 2. Those were both characters that had appeared in the [2002] Spider-Man game that I really wanted to revisit, along with the Lizard. We were originally going to have a sewer system that ran under the city in Spider-Man 2, and that also ended up getting cut until Spider-Man 3. We had stealth missions in Spider-Man 1, and it had been kind of a staple of some of those earlier Spider-Man games. Our system in Spider-Man 2 didn’t really support it super well, though, and so I don’t remember having serious discussions about that during Spider-Man 3.

James Zachary: We had a section where [Kraven the Hunter] came back in the second one, if memory serves, and we ended up cutting a lot of his stuff. Because it was him and Calypso, and we ended up really trimming back on that aspect of it. The thing I remember the most from that time was just a lot of the stuff that would come in—because we were getting the game closer and closer to having it complete, so more and more eyeballs were getting on it on the movie side and the Activision side. So I do remember some notes coming in.

Like, we made Black Cat really sexy, and we’d planned on that, and I remember them coming back and saying, “She’s too sexy.” So we had to go in and fill her out a little more. And then we had a lot of cutscenes and moves that sold that sexiness of her, so we had to like go in and lift cameras, and change some poses, so that she wasn’t swinging her hips so much. Try not to have her feel so flirty toward Spider-Man. I remember doing a lot of those changes, and those kind of hurt, because she’d been done for a long time. You’re getting close to the end, and then all of a sudden you have to go revisit these animations and this character that everybody actually really liked, because she was so sexy. And you’re kind of like, “Why didn’t that get caught two months ago?”

Matt Rhoades: Boy, it was really tough. We were building something from the ground up that we’d never done before, using a lot of completely new technology in terms of streaming and so forth. And, honestly, delivering it on three platforms—we had a really good multi-platform pipeline, so of all the logistical challenges, that was probably one of the easier ones, just because we had that established pipeline in place. It was much more that the schedule was just this Sword of Damocles hanging over our heads. There was no way to move that [June 2004] date.

And so we were really kind of under the gun. There was no way around it, and we were doing simultaneous release not only on all three consoles but in multiple languages. So there were something like thirteen or fourteen languages that we were doing, which means that not only did our work have to be done, and all the writing and recording had to be done, but then it had to be translated, and it had to be recorded in French and German and Spanish. I don’t even remember all the languages that it was in. So it was very, very stressful.

Spider-Man 2 should go down in history for having famously bad crunch practices.

Tomo Moriwaki: We knew we had found something, because we couldn’t stop playing the game at the office. It’s the only game that I played pretty extensively for at least another six to eight months after I’d shipped it. And played it at home. I used it like methadone to get off the drug, and to kind of ramp myself down. Like, the swinging around the city—you’re too stressed out, and you just swing. And I think all of us were self-medicating on Spider-Man swinging at the office during Spider-Man 2 pretty regularly, especially as we got towards the even crunchier last quarter of the project.

Spider-Man 2 should go down in history for having famously bad crunch practices. I think we crunched for a solid nine months, and I don’t think we entirely noticed. And we didn’t have enough people that would complain about it. We were all too young, and it didn’t get on the radar for being a bad crunch case, but the numbers just don’t make any sense. Back then, [with] every project, I felt exhausted afterward. I didn’t have any other life. I just turned the volume up to eleven, and gassed the pedal till I passed out, and woke up, and just kept doing it.

But it’s interesting—the end of Spider-Man 2 does mark this kind of waking the hell up and taking a look at what we do, and going, “Yeah, shoot.” You inevitably feel defensive when someone says you make these bad calls and you hurt people, but it was a good wake-up: Hey, it’s not efficient. What we do isn’t efficient. We literally just run until we fall unconscious, and then get up and run again. And then, because so many of us do it, it probably creates pressure for other people to follow suit. And if they don’t want to do it, that must be terrible. That was the first conversation I had with myself about work-life balance, probably.

James Zachary: It wasn’t until—like now, I work at Zynga, where I can really see how the culture was different. I don’t want to say we were renegades, but back then no one really did that many games, and there wasn’t really a strong, mature industry, so we were all kind of just doing what we thought was right, you know? Working hard, working long. And we’d also play hard, as well.

Matt Rhoades: We were spending a lot of time in the studio together, especially as the project went on. Everyone was working a lot. I mean, we had bitten off way more than we could really chew. But yes, we were also—the design team, at least—we were definitely socializing outside of work. And I’m still really good friends with Tomo. I’m definitely still friendly with most of the other people on that team. It turned into a brothers-in-the-foxhole kind of thing. We definitely bonded on that project.

Tomo Moriwaki: Especially after Spider-Man 2 had shipped, that [cross-team] rivalry appeared at least a few times where it was clear that there were some problems. And, for me, it was crazy. Like, I just spent the last twenty-six months here. And it’s the end of the project. It’s like I put my head above water—I had matured quite significantly over the course of Spider-Man 2, as well—and I’m like: Oh my god. There’s a social problem.

James Zachary: The success helps. If the game wasn’t as successful as it was, it probably would’ve been a little more painful, but a lot of people really enjoyed the game, and it was considered a huge success for Activision at the time. But back then you sold two million copies, and it was a success.

Tomo Moriwaki: Spider-Man 3, generally, started up right after Spider-Man 2. We did have a young team. I think we made a lot mistakes in the way in which we handled our communication with both the higher leadership of Treyarch and the higher leadership of Activision. I think some bridges were burned—myself burning some of them. It all felt so damn normal. But there was a point when I realized that we were all dysfunctionally defiant. We were a very consolidated bloc, we didn’t have much dissent within the team, and we were all just too young.

James Zachary: I don’t know what bridges were burned. Obviously, when you crunch that hard, and for that long, tempers do flare. I mean, you just can’t help it. It’s human nature. But people are tired and they’re burnt out and they’re exhausted. So little things that, if you asked somebody who’s refreshed and working a normal week, and it wouldn’t bother them—it just gets kind of multiplied after you’re working eighty-hour weeks, and your Saturdays, and you’re having a hard time, and you’re eating junk food.

I think Activision was doing their best to help us out. Sometimes we would just laugh at them, and say, “Okay, you don’t quite understand the constraints we’re dealing with right now.” But I think there was a respect on both sides. I didn’t really see any sort of bridges burned there. There were some employees that got pretty angry with some stuff, and they’d send out nasty emails, but I don’t think there was anything too nutty.

Jamie Fristrom: For Spider-Man 3, I went back, put on my prototyping hat, and made some stealth missions. And they were a lot like the stealth missions in the Neversoft Spider-Man for the original PlayStation. You’d shoot up to the ceiling, you’d be in some installation, there’d be guards walking around, and you’d shoot up to the ceiling—and the guards wouldn’t see you, because you’re above their line of sight or whatever. Kind of like what later happened in the Batman: Arkham games.

And so you’d crawl along on the ceiling. Sometimes the view would be straight up and down, so you could sort of see what you’re doing; sometimes you’d be in a corridor, and then you’d do these takedowns. Again, a lot like what later happened in the Batman games. You’d press a button when you’re over a guard, you’d drop down, and you’d web them up and leave them hanging from the ceiling or splattered on the floor. And unfortunately, in my opinion—some people on the team really liked those levels, but other people were like, “No, don’t make a stealth game. We want to keep it accessible, and stealth’s no fun, and stealth isn’t really what Spider-Man is about.” And, in the end—this was Spider-Man 3—I’m like, Okay, I guess enough people don’t like it, so I’m gonna bail on it. And then I left the team several months later. So it wasn’t my baby at that point anyway.

[Spider-Man 3] was a three-year project, and I was only there for the first year, so I had very little influence over that whole thing. There were underground levels in Spidey 2, but those were more straightforward beat-’em-up levels, where you were gonna fight Lizard minions. It actually wasn’t until the beginning of Spidey 3 where I was trying to prototype missions, and in my mind it was like, Yeah, this is the next cool thing. It’s gonna be as awesome as prototyping the web-swinging in Spider-Man 2. But unlike Spider-Man 2, it didn’t get off the ground. I wasn’t able to sell it to other people on the team.

VII. Infinite

Spider-Man 2 went on to become the best-selling movie tie-in of the year in the United States, but it was also a hit with critics. Despite a harrowing crunch cycle and countless technical hurdles, here was a game that dared to be better than the sea of mediocre licensed titles that had come before it—an example of what superhero games could truly achieve. It was a masterpiece.

Tomo Moriwaki: Any game I’ve worked on, after it shipped, I never saw it again. And I always have plans to. And it’s not even that I have contempt for the game. There are some games I’ve played for a few thousand hours—World of Warcraft, and World of Tanks, and Warframe. But aside from those, you put enough time into a game, and you don’t need it anymore. Once you’ve consumed all the uncertainty in an experience, there’s really no need to have the experience anymore. Right? And so, for games that we work on [laughs], we have consumed all the uncertainty in those games. Except maybe the Spider-Man swinging experience, because it is, quite possibly, infinite in the way in which you can explore and control yourself.

Matt Rhoades: I feel like people kind of fundamentally misunderstood the swinging. They would try it, and there was a lot of friction. When you first started playing Spider-Man 2, you could not swing well; it was not something that you could just pick up and sort of go. Because we were using a lot of real physics—even though we were faking a lot of stuff, as well—you were fundamentally kind of out of control. And you had to learn how to manage that, rather than trying to actually be fully in control. So when people would talk about changes that they were going to make to Spider-Man’s swinging, whether it was in Ultimate Spider-Man, or whether it was in Spider-Man 3, or any of the subsequent games—after Spider-Man 3, I haven’t actually played any Spider-Man games. The PS4 one will be the first one that I have picked up, and will play, in a long time. So I don’t want to cast aspersions, but I think that the idea was always, “There’s too much barrier to entry for me; we need to make it simpler; we need to make it easier.”

And that is not an invalid design goal. But if you’re going to do that, you need to kind of examine first what it is about our swinging system that was so compelling. It had depth. It was a system that you could master. It had all this intricacy to it that made it genuinely fun to pick up the controller, and once you got past that initial friction and were swinging around, you were saying: “I wonder if I can do this. I wonder if I can do that. Oh, let me try this.” And you were really very empowered by the system to be as cool and as Spider-Man-like as you wanted to be.

And I think, in simplifying the systems, what was lost a lot of times was that depth, and it wasn’t replaced with anything. So it was a missed opportunity, because I’m certainly not gonna sit here and tell you that there was no room for improving the swinging system in Spider-Man 2. It was pretty rough. But because of this sort of misunderstanding of what it was that was wrong with the swinging, the corrections that were made, I think, were the wrong corrections.

Tomo Moriwaki: There are two pieces to it. One, a mechanical experience whose complexity is beyond our consciousness, let’s say. So it only needs to be one bit more complicated than I can wrap my head around, and I can never be certain of everything. But then you add in this humongous serving of player freedom and choice. In some ways, I think those two things combined to make Minecraft the big success that it is today. But I think you took those two factors, and the kind of visceral exhilaration of moving through the space, and that feeling of speed, and it was just a really good experiential drug. My mind was never satisfied; I could always explore more. There was no force in the universe that was telling me what to do, so I was free. And I got a little bit of good speed juice, adrenaline, in the process. So that, I think, in a nutshell, describes why it has so much longevity. And we did a damn good job of it.

Jamie Fristrom: I’m bragging here, but that web-swinging system would not be there if it wasn’t for me. If I hadn’t made those first prototypes and championed them so strongly, it would not have happened. If I was left alone on the project, though, it would have sucked. I needed the contributions from people like Eric Pavone and Andrei Pokrovsky and Jason Bare and James Zachary. Without all their help, it would have been pretty crappy.

Tomo Moriwaki: When it comes to certain features, you get it working and then you move on to the next feature. Whereas the player package for Spider-Man 2 was something we started at the beginning of the project, and we literally never stopped spending a lot of our thoughts on it. Also, because we kept playing it, and the more we played it, the more we’d come up with a lot of interesting ways to refine it or go forward with it, and that momentum carried all the way through to the end of the project. And, really, past the end of the project. It was this kind of living, breathing thread that never stopped evolving, from the very first day of the project all the way to the day it shipped. So there is a lot of real carefully tuned depth in that control experience.

James Zachary: Spider-Man 3 is where I really felt we hit our stride on the animation side of things. And then I didn’t do [the 2012 Amazing Spider-Man adaptation], which was a blessing and a curse at the same time, because I actually do miss that character a lot. But after ten years of doing ’em, I needed a break.

Jamie Fristrom: I vividly remember Web of Shadows, which was a pretty fun game, but [being] like, “What? You can attach to the sky now?” Web-swinging still feels good in that game. When you do attach to a building, you still have that feeling of momentum. But then—I didn’t play it much, but in [the Amazing Spider-Man game] you just looked at where you wanted to go and pressed a button, and it played a cool movie, and you ended up where you wanted to be. [Pauses.] That stops feeling like a game to me.

Tomo Moriwaki: It was a really good experience after the fact. I got to learn a lot. I gained orders of magnitude of perspective. The end of the project was this amazing and wonderful and depressing moment in my life. I’d just deployed too much of my life, too much of a percentage of my life energy, into Spider-Man 2 for so long. And it’s not like there’s live ops, like there is now. When it was shipped, it was done. We didn’t have to do anything. That was like a brick wall that I’d been pushing, putting all my energy into, day after day, hour after hour, just evaporating. Kind of fell flat on my face and started thinking about what the next step was. Oh, wait, maybe I should think about who I am and where I’m headed and stuff. I also had a kid on the way, and so it was a period of significant maturation for me.

Matt Rhoades: I don’t remember, specifically, what people were saying at the time. I think mostly what I internalized was the negative feedback—people getting frustrated by the amount of repetition in the city missions and things like that. But the thing that people have said to me repeatedly over the years that always makes me smile is, people will say, “Spider-Man 2. You know, I can put it in, and I can get ahold of my controller, and I can just start swinging around, and I can just do that for hours.” And I think that that’s a great place to be. If someone can pick up your game, and they’re not even really engaging with it beyond this core system, and they’re having a good time and they just want to keep going, that’s fantastic. So I love that about the game.

Jamie Fristrom: We were kind of obsessed with GameRankings. Remember GameRankings? I don’t know if it’s still around—people tend to use Metacritic now—but GameRankings was the big game-rating aggregator site back then, and we would look at it every day as new reviews came in and watch our score go up and down—partly because we wanted to see what people thought, but also partly because our bonuses were actually tied to our GameRankings score. That was something Activision built into our contracts. But it was such a relief for me. It was like, “I love this thing we’ve done, but is it accessible? Are people going to get it? Or are they just gonna try it and throw the disc out the window?” So it was really gratifying that people dug it as much as we did.

James Zachary: Oh my gosh. That’s always the hard part of any sort of creative field. You’re like, “What are they gonna think of our game?” And you start to second-guess yourself a lot. So you’re like, “We did everything we could, but maybe we could’ve done more. Maybe if we’d worked that one other weekend, we could’ve done something.” So when the reviews started to come in, you start reading them, and I’d always go right to the animation side of it first because that was my responsibility. And a lot of them were super positive, and they didn’t see a lot of this stuff that I saw and wanted to fix, or where we had to do the animation in like half a day. They were just like, “Felt like Spider-Man. Dynamic posing. Loved it—was snappy, responsive.” I was like, “Oh, yes.” And then I actually started making a collection of feedback, because I knew we were doing another Spider-Man, so I wanted to address everything in the next game.

So I created a document that had all the pros from the animation, and then all the negative sides from the animation, and I remember one day looking at it—I think we had to do [employee] reviews or something—so I opened it up, and most of the stuff was positive on the animation. We had very select things for our negatives. Very, very few cons. And at that moment, I was like, “Okay, we did a good job.” But it took a long time before I felt like that. I always thought, Okay, the next review is gonna see the stuff I saw, or the stuff we weren’t able to fix. And, you know, they never did.

Tomo Moriwaki: It was a really, really good time. It was the defining challenge of my entire career.

Jamie Fristrom: What I found when I was working on it is, I would sort of get lost in it, you know? It’s like, “Oh, I’m supposed to be checking to make sure I just fixed a bug, and then compile and run.” But I’m just swinging along, losing track of time.

Matt Rhoades: I’m really proud that we got it out. It was not a foregone conclusion that that was going to happen. And it’s a game that is greater than the sum of its parts. I think the fact that it does continue to show up not just on lists of the best Spider-Man games but on lists of the best superhero games, to this day, is really a testament to the quality of our design.

At the time, there was this feeling that the first game had sold a bazillion copies, and the movie had been a huge hit, and the second movie was a huge hit, and so the second game sold a bazillion copies. It was hard to kind of separate the success of the game, financially, from just sort of being a cultural product of the success of the film and the success of Spider-Man in general. So I’m really proud that the game is something that people still talk about and get excited about when they find out: “Oh, you worked on Spider-Man 2!” That people are genuinely excited about that, all these years later, is really cool. To make something that lasted—that’s a hard thing to do.