The Oral History of EVO: The Story of the World's Largest Fighting Game Tournament

The history of the Evolution Championship Series as told by the people who have been there from the beginning.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

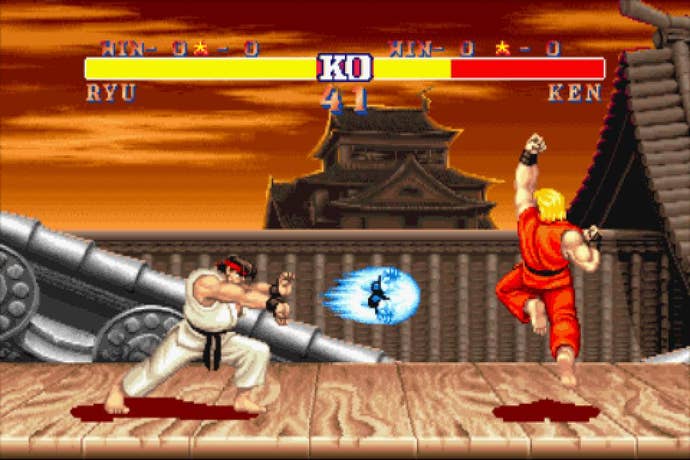

You know him and his trademarks: The headband, the fireball, the stoic demeanor and friendly rivalries. When you see a Ryu match, you see people getting baited into jumping at him so they can meet the business end of a Dragon Punch, then maybe an un-ironic win quote with some affirmation of the opponent's skill. Ryu is the zero point at which all fighting games grew and evolved, so rock solid is his visual and play design.

For a series of video games about people punching each other in the face for 99 seconds, the Street Fighter games have an elaborate, even absurd lore to them. But what it all boils down to in the end is a man traveling the world for strong opponents, and for no other reason than to better himself. It's competition in its most pure, distilled formula: win and move on, lose and learn from it. When fighting game players, then, emerge from their local scenes with that same drive to travel the world for strong competition, they know what they need to do: They go to EVO.

This weekend, The Evolution Championship Series will hold its yearly tournament in Las Vegas, with over 2600 strong for Street Fighter V alone and roughly 1500 each for two separate Smash Bros. games. Through the halcyon twilight of arcades in the 90s to the lean Dark Age of fighting games in the early 2000s, EVO has had continued attendance growth year-over-year, and outlasted other large events in the world to become the place to test your mettle. For this genre of games, there is no higher trophy than that of EVO champion.

Getting to this point wasn't without its growing pains, though. As the name implies, EVO evolved from local scenes on the West Coast of the US, growing in size and scope from the Battle By The Bay in the late 90s. Now just over 20 years since those first gatherings, we spoke to the tournaments founders—Joey "MrWizard" Cuellar, Tom Channon, and Seth "S-Kill" Killian for a robust history lesson about where the event began and how it became the mountain that pro fighting game players train tirelessly to ascend. We also spoke to three legendary competitors—John "Choiboy" Choi, Capcom producer Peter "ComboFiend" Rosas, and Daigo Umehara—for their perspective on the birth and growth of the tournament that put them on the map.

This is the complete history of EVO.

Note: This story is several interviews collected over several months. They have been edited for clarity and to reduce redundancies.

Local Legends

The fighting game community got its start in arcades like the Southern Hill Golfland in Southern California. It was there that a hunger for Street Fighter II competition drove fans to begin organizing tournaments. Soon, the competition that we would come to know as EVO began to blossom.

Joey Cuellar: I was playing at Southern Hills Golfland down in southern California. This was considered the mecca of fighting game arcades back in the day.

Tom Cannon: Of course, fighting games grew up in arcades, before the days of consoles or PC-Gaming. The crazy thing about the tournament scene is that it happened basically everywhere at once. Players would gather at arcades to play and compete, and it was just a totally natural thing to say, "Hey, let's hold a tournament!"

So, while I played at this fairly small arcade in Albuquerque, NM, you had much bigger, much more competitive events going on in places like New York, the Midwest, and California.

Peter "Combofiend" Rosas, Producer at Capcom: The first tournaments I ever entered were at Southern Hills Golfland in Southern California. Back then I was in high school and extremely nervous! I really wanted to prove myself against all the players, both known and unknown, while also representing my local arcade. This would cause me to really psyched up. That said, I loved every second of it. The first few tournaments were definitely an exercise in how to maintain composure under the most stressful environments.

John "Choiboy" Choi, original competitor: Street Fighter II cabinets were ubiquitous in laundry mats, bowling alleys, 7-11s, video rental stores, etc. Everyone and their mama played SF back then so it was easy finding competition when first starting out. I was not old enough to drive yet so I rode my bike to my local 7-11 and that was my original training ground. As I started to get better in the game, I started traveling farther to find good competition. I eventually settled on San Jose Golfland as my main training ground as I could bike there. Later when I was finally able to drive I made it out to other arcades and eventually settled on the infamous Sunnyvale Golfland where [Battle by the Bay 3] took place. I settled here because it had the best competition. After a while tournaments became popular at arcades, there was a period of time when I competed in 3 tournaments a week. A lot of players at this time was literally doing Ryu world warrior mode and going from tourneys to tourney and various arcades. I have very fond memories of these times.

The Battle by the Bay

The local arcade scenes were still flourishing in the mid-90s, and the rise of the Internet made it easier to organize regional tournaments. The Battle by the Bay was born in 1996, attracting California's top fighting game players to Sunnyvale Golfland for a massive tournament. In the years that followed, it grew to include competitors from other regions, then other countries.

Tom Cannon: So back in the mid-1990s the U.S. tournament scene had coalesced around a few hot-spots that were largely recognized to have the very best players. There was Chinatown Faire in New York, Super Just Games in the Chicago area, Sunnyvale Golfland in northern CA, and Southern Hills Golfland in southern California.

[At this time] I was in college, studying Computer Science in Norcal. Lucky for me, Sunnyvale Golfland, one of the hottest spots for competition in the whole country, was 13 miles south of campus. So twice a week I would take the bus down to play, usually one day to practice and another day to compete in the local tournament there.

These were the spots that got written up in game magazines and were the places you really needed to play in to make a name for yourself. And there were rivalries between these player groups, particularly between the Northern California (NorCal) and Southern California (SoCal) players.

Tournaments were almost entirely local back then. It wasn't like today where top players are able to fly around the country to a new tournament every week. Meetings between these player groups were fairly rare, so they were high stakes. Who came out on top very much dictated who had bragging rights for the next year or so until the next big tournament.

John Choi: I was young and [it] just felt it was business as usual. I could not fathom how big the scene would blow up and how long it would last. I was just focused on finding good players as competition was fun for me. I kept myself busy by going to as many tournaments as possible to soak up information and only wondered how good other regions were. There was no internet or cell phones back then so the only way you learned was by going places physically and talking to people.

Tom Cannon: So, remember, at this time you have a ton of local scenes, centered in arcades, competing more or less in isolation from each other. Big regional or national tournaments were pretty rare.

But gradually, a trickle of players (myself included) were gradually finding each and talking strategy over internet message boards. This was before the web, so everything was just text. There was no GameFaqs, no YouTube, and no real way to share knowledge about the game, except literally typing up these lengthy descriptions of play patterns, counterplay, and tactics that we were discovering or had seen in our local arcades.

So, you'd get these enormous, 50-100 post strategy threads, and they usually devolved into massive s**t-talking, about how terrible the other guy was, because the garbage he was spewing in the thread was totally off-base.

This is actually how I met Seth. Seth was one the most active posters on the message boards, and a legendary s**t-talker. We would go back and forth for days arguing over all aspects of play, and we both basically probably thought the other guy was trash at the game.

Anyway, Battle by the Bay was basically a "put up or shut up" moment for all these internet folks who all thought they were the best. Because we held it at Sunnyvale Golfland, we also were able to attract all of the top California talent, which ratcheted up the stakes by about a hundred-fold.

Joey Cuellar: It was mostly newsgroups and word of mouth back then. The internet had just started so people jumping on there was mostly at colleges and universities.

One-hundred percent of play was happening in arcades back then, so if you were a Street Fighter or Mortal Kombat player, you would sort of habitually check out any arcade you ran across that looked like it might be a spot for serious players.

Inevitably someone would run into this amazing player or players at some other arcade, then run off and tell the folks at their local arcade. So even really early on there was a rivalry dynamic between groups of players. It started off as arcade vs arcade, then gradually grew to regional, national, and international competitions.

Enter Japan

Tom Cannon: Our tournaments have always had an international flavor. Even Battle by the Bay had an international presence, from Canada and Kuwait if you can believe that one!

The fact that we were seeing global interest, right from the start, has actually had a big impact on me in seeing the potential of these games to bring people together in incredibly powerful ways. It's just such a great experience to meet other people who don't look like you, don't talk like you, and have a different culture, but you both have a deep passion for the game.

When it comes to the Japanese, things started out with invitations, going both ways. The first was a 5 on 5 U.S. vs. Japan invitational back in 2000 that Peter Kang put together as a component of his fighting game documentary, Bang the Machine. Later, we had the U.S. Alpha 3 national tournament, where the winner (Alex Valle) competed against the Japanese champion (Daigo Umehara) in an exhibition.

Though these invitationals, I think both countries got to understand that we all had the same hype and drive for the game, and Japanese players gradually started to attend U.S. majors on their own. It was just a trickle at first, but it steadily snowballed, to the point where we have over 100 Japanese competing every year at EVO, along with competitors from all over the world.

Joey Cuellar: I think it all started with Daigo coming over here to play Alex Valle in Street Fighter Alpha 3. That was really the first time an exhibition got worldwide coverage and what opened the door to awareness of fighting game tournaments across the world.

Daigo Umehara: I think I first learned about EVO through a gaming friend at the time. There were four titles: Super Street Fighter II Turbo, Street Fighter 3 Third Strike, Guilty Gear, and Capcom Vs. SNK 2. I could enter, and I thought it was worthwhile participating. Looking back, it was the first overseas tournament I voluntarily entered.

Though I can admit now, I dreamed a little bit that people might have noticed me if I had won all the four titles. I was young and felt really strong. In fact, I took 1st place in 2 titles and second place for the other two. That's how much I was at the top of my game.

Peter Rosas: Japanese players were always regarded as the best, so when more and more started attending EVO, I felt there was immense pressure to beat them and represent the US! It was interesting because a transition happened where local or even national rivalries weren't the focus at EVO. This is where global rivalries were settled.

Daigo Umehara: It takes a lot of courage and money for the Japanese to make it to an overseas tournament, especially back then. Considering they still made it, including myself, proves that it did have a great impact on us. What attracted us most was, first, was a monetary prize. We could not and still can't get any monetary prize in Japan (due to a law), so it was unheard of. Additionally, a great number of participants that we had never seen before were at a tournament. It was very exciting. It immediately gave us a sense that it would be an extraordinary, such a fun event. Most of the Japanese probably felt "I will get them", given the skill level of Japanese players were so much higher compared to other regions back then.