The Making of Fallout: New Vegas: How Obsidian's Underrated Sequel Became a Beloved Classic

From its beginnings at Black Isle to classic DLC like Lonesome Road, we dive into the history of one of the best RPGs ever.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

If you want to know how relevant Fallout: New Vegas still is today, consider what happened when Obsidian founder Feargus Urquhart and director Josh Sawyer went to a local middle school for a game design competition. Given an opportunity to ask the judges a question, the competition's winner-a 7th grader who couldn't been older than six when New Vegas was first released-asked Sawyer: "Hey, are you going to update your mod anymore?"

Sawyer was flabbergasted.

"I was like, 'What? How does this kid, one, know about New Vegas, two, know about my mod, and three: that's the burning question that he wants to ask'?"

But that's the kind of cultural cachet that Fallout: New Vegas has these days. In the wake of Fallout 4, which has become something of a whipping boy for the Fallout community, New Vegas' legacy is stronger than ever.

Check Fallout: New Vegas' Steam page, and you'll find that it enjoys near universal acclaim, with player after player calling it the best game ever. A 2016 Kotaku article featured the headline, "Fans' Intense Love for Fallout: New Vegas Must Be Weird for People at Bethesda."

What do fans want even more than Fallout 5? Fallout: New Vegas 2, obviously.

It's hard to believe now that the game that enjoys so much acclaim once missed its Metacritic score by one point, depriving Obsidian of their hard-earned bonus payments. It's stranger still to read passages like this one from 2010:

New Vegas is a proclaimed non-sequel, and it shows. By bringing little else new to the experience and with it being as buggy as ever, New Vegas could have been adequate as a smaller-sized expansion disc. Instead, it's a game where the play clock is measured in time spent plodding through loading screens and not actually doing much.

Somewhere along the line, things changed. Instead of fading into history, New Vegas became a classic. So what's different now? Maybe it's best to start from the beginning.

The Beginning

Urquhart never quite dared to dream that he would get to work on another Fallout. Just a few years earlier, he had departed amidst the slow collapse of Black Isle Studios, leaving Sawyer and a skeleton crew to take on the impossible task of finishing Fallout 3.

Black Isle's Fallout 3, called "Van Buren," was very different from the version that ultimately came out of Bethesda. It would have included many of the aspects that ultimately defined Fallout: New Vegas, such as the setting, but the combat would have been a hybrid of turn-based and real-time elements. Instead of The Courier, Van Buren would have featured an escaped prisoner who later uncovers the plot of a mad scientist named Presper.

The death of Black Isle Studios and the loss of the Fallout IP to Bethesda seemed to preclude any chance of Urquhart and company finishing what they had begun at Obsidian. But then they got the chance of a lifetime. They wouldn't get a chance to finish the game they had called Van Buren, but they would get one more chance to put their own stamp on the franchise they had helped to create.

Taking the reins as director was Josh Sawyer, who had fought to finish Black Isle's Fallout 3 until the very end. Joining him was Chris Avellone, author of the Fallout Bible and a tremendous designer in his own right, who wrote characters like Rose of Sharon Cassidy and developed the DLC. John Gonzalez, who would later go on to work on Horizon Zero Dawn, helped to develop much of the core story. Old-school Fallout fans were getting their wish: For one game, at least, Black Isle was back.

With the team already deeply familiar with the Fallout universe, the initial concepts came together quite quickly, Urquhart remembers. "The first thing we said was, 'Well, we're going to do the West Coast.'"

It was a natural choice. Fallout 2 had been set in Oregon and Van Buren would have been set in Arizona, Nevada and Colorado, so shifting the setting back to the West Coast offered the opportunity to establish a connection between Bethesda's vision and the franchise's roots. It also made it possible to bring back the New California Republic, which had last been seen spreading its roots out west.

Obsidian's team tossed around any number of ideas. They debated setting it in New Reno, which had been a prominent location in Fallout 2. They thought about making it possible to play as a ghoul before ultimately shelving the idea due to technical challenges with how the armor would work.

Before long, Obsidian had most of the particulars nailed down. The NCR would return, factions would play a heavy role in the story; and most importantly, it would be set in New Vegas.

New Vegas was kind of the perfect Fallout location. The Mojave Desert brings its own Mad Max vibe, and Vegas itself automatically conjures images of the '50s and '60s: Elvis, the Rat Pack, the mob.

Sawyer was happy to push that vibe a little. "It kind of felt nice because we had covered the '50s with Fallout 1 and Fallout 2. So pushing a little bit into the '60s didn't feel bad, because it was like, 'Okay, we're continuing ideas from Fallout 2.' And we're venturing into a later decade, but the cutoff I used was JFK's assassination. We couldn't use music or anything past that point."

The gangs inhabiting the strip further embodied this vision of Las Vegas. The Omertas represented the real-life mobsters that ruled Vegas in the 50s and 60s; the Chairmen represented all the denizens of the Strip wanted to look cool but were really just trogolodytes, and the White Glove Society was pure vice. As always, the apolocalypse was meant to strip away the real-world location's glossy exterior and reveal the rot beneath, with a particular emphasis on Vegas' greed and excess (indeed, one of the original working titles for Fallout: New Vegas was "Fallout 3: Sin City").

For good measure, Sawyer implemented gambling. Amusingly, Sawyer actually hates gambling, but he felt that it was necessary to meet audience expectations. "You're making something for an audience, and understanding their wants, and needs, and their desires. And it doesn't really matter that gambling in New Vegas isn't particularly consequential. It's like 'I'm in Vegas, dude! Let me roll some dice or spin a roulette wheel, or do something.'

In order to get a feel for the actual location, Obsidian obtained data from the U.S. Geological Survey, which they included in their pitch to Bethesda. Sawyer also hopped on his motorcycle and rode to Las Vegas, where he explored the outskirts of the Strip and the surrounding area.

"He made a big deal about the freeways," Urquhart remembers. "He said, 'We need those freeways to help people understand, as the thoroughfares in the Valley, to know how to get from place to place.'"

Soon, Sawyer was mapping out the entirety of the Wasteland with orderly designations like "A-1" and "A-2." Their main rule of thumb, courtesy of Bethesda, was that from any landmark in the world, you had to be able to see at least three other landmarks. To that end, one of the first landmarks Obsidian designed was Dinky the Dinosaur—the massive T-Rex statue that serves as Boone's sniper nest—with the goal of ensuring that it was visible from as far away as possible (the real Dinky is actually in Cabazon, California-some four hours from Las Vegas).

As the team began work on Fallout: New Vegas, though, they ran into a bit of a problem: none of them were familiar with Bethesda's Gamebryo engine. "We had no experience working with that engine. The first person who came here who had experience working on the engine was Jorge Salgado, who was the modder who had made Obscuro, an Oblivion overhaul, while the rest of us were completely clueless," Sawyer says.

Obsidian's inexperience presaged many of the technical problems Fallout: New Vegas when it was later released. Still, with the basic location established, and the Mojave Wasteland mapped out, Obsidian was officially off and running. And they needed to be: they had just 18 months to finish a massive open-world game.

Surviving in the Desert

From the start, Fallout: New Vegas was intended to be an experience that equally appealed to hardcore fans and newcomers. It rebalanced the progression to force players to specialize, and it introduced a new Hardcore mode that was meant to evoke the sense of surviving in the desert. Crafting and weapons mods was dramatically expanded, and it became possible use ironsights to shoot.

But while it was more hardcore, Sawyer also wanted to make sure that the new features were largely optional. "Hardcore mode was not a tremendously difficult thing to implement, but it as a cool thing. It was a hardcore thing. And it's something that you can opt into. If you don't want to play it, you just leave it alone. And so we really approached it from that perspective, like, 'Hey, if you want a more challenging thing that makes you feel more like you're struggling in the desert, then here's this aspect for you.'"

On that front, he remembers an argument he had with Bethesda's Jason Bergman about the Living Anatomy perk, which offers +10% Doctor and +5 damage per attack against organics.

"I wanted to bring Living Anatomy in and have it show you the Damage Threshold and the Hit Points of the creature that you were targeting on the actual HUD," he says. "And he was like, 'Ahh, don't put numbers up there.' And I'm like, 'You just don't buy the perk, Jason!' Like, you don't have to take that perk," he remembers.

Crafting was another example of optional depth. "[I]t was just looking for those ways to get the characters that really want to dig in, and have more to play with. Like from a numbers perspective, or they just want to analyze stuff a little more. But there was always a line where I said like, 'You know what? If we push on this too hard, it's going to turn people off.'"

Much as Obsidian wanted to add to New Vegas' mechanical depth, though, the biggest strength of Obsidian's Fallout was the writing, the quest design, and most especially, the companions and the factions.

New Vegas' companions are frequently cited as one of its best features. Their purposes vary widely: some of them have relationships with the factions (Boone, Cass, Veronica); some are meant to be callbacks to previous games (Lily, Arcade), and some are just plain fun (Rex, the cybernetic dog). Most have well-developed backstories, and a few of them play into some of the best quests in the game.

Fun as the companions are, though, the real heart of New Vegas is its factions. Where choosing factions in Bethesda's games is often a binary choice, Fallout: New Vegas operates on more of a gradient. Factions will react positively or negatively depending on your actions, and only extremely hostile acts (or wearing a hostile uniform) will turn them fully against you.

"One thing that I had noticed in Fallout 1 and 2 that I wanted to address in [Baldur's Gate III: The Black Hound] as well as Van Buren, was that sort of... You know, I kiss a baby and then I punch an old lady in the face, and the result is that no one has an opinion on me?" Sawyer says.

You're ultimately meant to bounce between the game's three main factions—the NCR, Caesar's Legion, and Mr. House—before finally setting aside their individual flaws and joining the one you find least offensive (or simply striking out on your own).

This is a large part of Sawyer's personal philosophy when it comes to designing RPGs. Sawyer is a believer in freedom in the old-school sense. He wants players to feel like any choice they make is valid, whether they team up with the NCR or become a Wasteland axe murderer.

Everything about Fallout: New Vegas' journey is about getting you to the point where you get to make interesting choices, the main hook being that you're a simple courier who has run afoul of powerful forces without realizing it. As the camera pulls well back from the Strip, we see someone digging a grave as a figure lays prone on the ground.

"This must seem like an 18 karat run of bad luck," a man in a checkered suit tells The Courier. "But the truth is, the game was rigged from the start."

Then he pulls the trigger.

Your journey to find the man in the checkered suit takes you to New Vegas—the nexus point where all the factions converge. In the early going, you're pretty much just another desert dweller passing through (Sawyer likens it to spaghetti westerns and the Man With No Name). But once you step into the Lucky 38 for the first time and meet Mr. House—the Howard Hughes-like genius who wants to rebuild the Mojave Wasteland-people begin to take notice.

This is where you get to start to choose your faction by taking on quests on their behalf, and where things begin to get messy.

The NCR is a good example of what Fallout: New Vegas is aiming for. While they initially come off as the "good guys" in their fight to restore order and introduce democracy to the Wasteland, they are bogged down by beaurocracy and heavily influenced by psychos like Colonel Moore—a career soldier who is willing to do everything and anything to seize the Wasteland on behalf of the NCR.

Avellone doesn't necessarily consider the NCR sympathetic, but feels their qualities have some value in the world of Fallout. In his opinion, the companion Rose of Sharon Cassidy pretty much sums up NCR's bad side. Caught in the Caravan Wars precipitated by the NCR's expansion, Rose of Sharon Cassidy is a hard luck merchant who is perpetually bogged down in NCR paperwork.

"In many respects, NCR isn’t better than the Legion, and while the Legion has plenty of bad qualities, it's not cartoon bad: it's got some elements about it that NCR could stand to pay attention to," Avellone says. "I wanted the player to at least consider an alternate perspective even if they didn’t agree with it (it makes an antagonist more well-rounded)."

That brings us to the Legions. Ostensibly the villains, Caesar's Legion combines Mad Max with Roman cosplay, adding in a Klingon-like sense of honor for good measure. Originally conceived as a slaver faction for Black Isle's Van Buren, Sawyer took them and made them more of a Roman military society, using Colonel Kurtz from Apocalypse Now as an inspiration.

"I think that [Chris Avellone] and I had talked at various points about really liking these kind of Colonel Kurtz characters, where they wind up in these circumstances where they just sort of descend into this really savage, cargo cult leadership role," Sawyer says. "And so this idea of a follower of the Apocalypse going off into the wilderness, and emerging on the other side as this sort of God king of the tribes of the wasteland? I thought that was a really cool idea."

Your first encounter with the Legion is most likely to take place in the burned out husk of Nipton, where the town's populace has been decapitated, enslaved, or simply crucified.

You're meant to be horrified, but this is where New Vegas begins to toy with your expectations a little bit, Urquhart says. "What I say is, 'I like turns.' I like it when you get exposed to something, and then over time, you start to question your first impression."

As it turns out, Nipton was a town of thieves that trapped innocent passersby, and the Legion was meting out their form of medieval justice. Later, if you decide to meet with Caesar, you find a charismatic and often brilliant man with his own vision for reforming the Mojave Wasteland.

Caesar, interestingly, has neutral karma, which Sawyer says isn't an oversight on his part. "My reasoning is that his morality is so alien to everyone else, that it's just hard to even put it on the same axis as other people, because he's just thinking about it in a completely different way."

Sawyer is not inclined to judge whether you're supposed to sympathize with Caesar or not. His only goal is to offer rich, multi-dimensional factions with their own virtues and flaws, and let players choose for themselves. One of the chief pleasures of Fallout: New Vegas—and perhaps one of the biggest reasons that it has endured to this point-is moving between the main factions, working with and against them, and eventually choosing who you want to side with for the Battle of the Hoover Dam... if you side with anyone at all.

"A very common thing that I see is people who are like, 'I support the NCR,' and then they get to Colonel Moore and a few other people, and they're like, 'What about Mr. House?,'" Sawyer says. "And then they get to Mr. House, and then he's destroying The Brotherhood, and they're like, 'Independent New Vegas, it is!' So the mechanics needed to be robust enough to handle this swaying of the player, and we needed to have mechanics in there that allow you to remove negative reputation."

Such a complicated setup makes for a fascinating journey-one that gives you agency to make decisions based on your own biases and beliefs. But there is a cost to such ambition, especially when you're a small studio like Obsidian. And that price eventually had to be paid in full.

Cost of Ambition

Obsidian ultimately managed to push Fallout: New Vegas out in 18 months. It fit much of Obsidian's original vision; but as with every triple-A game, cuts had to be made.

The biggest casualty, Sawyer says, were the settlements east of the Colorado River. This area was meant to contain three Legion locations filled with quests and content, and would have ultimately had a very different vibe from New Vegas proper.

Sawyer regrets the cuts, "I think a lot of people have said, in addition to the Legion being just repulsive, they didn't have content to redeem them as a faction. Some people talk to Caesar, and they're like, 'Caesar is interesting. Crazy, but interesting. But the faction itself just seems like misogynistic psychos.' And there's nothing to really change that perception."

Ulysses was another casualty in the main game. Conceived by Chris Avellone, he would have been a companion sympathetic to the Legion. But the character just got too big, Sawyer says. "That character just became enormous. I mean, literally, we just couldn't fit in the game. I can't remember how many lines he was, but he was just gargantuan, and editing him would have been too hard. So that's when we decided like, 'Okay, we're going to save this for later.'"

In speaking on what he would have liked to tackle given the chance, Avellone also focuses on the companions. "If there'd been time and the inclination, having Sunny Smiles, Yes Man, Benny, Vulpes, Victor and others as potential companions would have been great. So would have Muggy (we wanted to, but adding a full companion through the DLCs that would work in the core game would have taken more time than allowed)."

Then there were the invisible walls, which Sawyer swears wasn't meant to block people from traveling places, but made a bad impression nevertheless. "[Designer Scott Everts] for the most part was trying to solve line-of-sight issues. And really just prevent things from looking ugly. It wasn't to prevent the player from going anywhere. Because, as people have seen, you can get to New Vegas from the beginning of the game. It's just really hard."

"But because you start off in Goodsprings, and you're in mountains, near the edge of the map, you run into a lot of invisible walls really early on, and it really was not our intention to like, 'Oh, no! You can't go that way!' It was like, 'Oh, crap! People are getting stuck.' People would get stuck in the mountains, right? And so we put up invisible walls to prevent that. But it was a mistake. "

Needless to say, when it came time to make the DLC, Sawyer made sure that invisible walls were minimized as much as possible.

Fallout: New Vegas ultimately came out on October 19, 2010, where it received solid if unspectacular reviews. Much of the criticism centered around New Vegas' bugs, which had become an Obsidian staple by that point. Scroll through news articles from the time and almost all of them focused on the crashes and technical problems that bedeviled Obsidian's opus.

Urquhart is mostly sanguine about the reviews. "I don't want to excuse it. It's hard to make a huge game," he says. "We'll just say that four months is about 64,000 hours of test. You send your game out and a million people buy it. In one hour, they've tested it for one million hours. So it's again, not an excuse at all. It's just when you make a big complicated game, it's just hard and we need to figure out how to make stuff that's just not as fragile and stuff like that."

Sawyer says he would have been a stricter director in hindsight. "If I had it to do over again, I would have tightened things up, I would have pulled things a little closer together. And included those Legion areas. And I also would have been more aggressive. I let our designers actually do a lot of crazy things, sometimes those things were really cool, sometimes they were really bad and caused a lot of bugs."

Both say they were ultimately not that concerned with negative reviews, even if they did wind up missing out on their targeted Metacritic score. They had gotten their shot and taken it. In another era, that would have been that, and Fallout: New Vegas might have faded into obscurity as a cult classic but not much more.

But that's not what happened.

Walking the Lonesome Road

As you might expect, a lot of fans differ on why they consider Fallout: New Vegas a masterpiece. Some will point to the infinite opportunities afforded by the modding community, others will praise the writing and the often clever quests. But a significant number of them will tell you that the DLC is where Fallout: New Vegas really came into its own.

There were ultimately four DLC packs—six if you included the Courier's Stash and Gun Runners' Arsenal. They were mainly spearheaded by Chris Avellone, who used the DLC as an opportunity to fill in some of the gaps with the lore and play around with the quest structure.

"I think that both Chris and I wanted to explore specific ideas that were risky within the main game, but were less risky within a DLC," Sawyer remembers. "Like in the first DLC, a big focus was on the feeling of survival, and feeling really desperate, and almost like a horror vibe, and so Dead Money had that focus, which... It would feel weird if you designed even maybe a big Fallout New Vegas level around that. But as a DLC, it felt like, 'Oh, cool. This is my trip to a horror realm.'"

In a subsequent postmortem with GameBanshee, Avellone said that the DLC needed to have narrative hooks within the main game so that players would pause to consider the connection. "[W]e took care to make sure there were narrative connections across all the DLCs as well to reinforce the 'things that came before' and how all these signature characters' paths changed the Mojave and the DLC space."

Sawyer agrees. "Chris and I had to collaborate a lot to make sure that the DLCs actually fit together with Fallout: New Vegas and the core game. He had a certain progression towards Ulysses in mind, and Honest Hearts needed to fit into that progression."

The reception to the DLC was fairly lukewarm at the time of their release; but like New Vegas itself, they have grown in esteem has passed, particularly Sawyer's Honest Hearts and Avellone's grand finale: Lonesome Road.

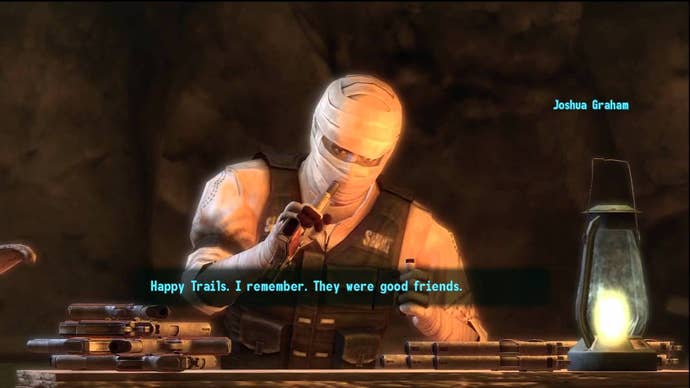

Honest Hearts was a comparatively simple and straightforward quest, but Sawyer wanted to use it to delve into a number of themes, particularly religion. It begins with meeting Joshua Graham: the famed "Burned Man" who is alluded to but never seen in the main quest.

The Burned Man was a nod to The Hanged Man from Black Isle's original version of Fallout 3. As originally envisioned, the Hanged Man would have been statistically one of the best characters in the game, but would have made negotiations problematic. His appearance in Fallout: New Vegas was a treat for longtime fans looking for a nod toward Black Isle's roots.

The subsequent centers around a war within Utah's Zion National Park and a mysterious character called "The Survivalist.

"I gave John Gonzalez the idea of who the Survivalist was," Sawyer remembers. " I'm like, 'The Survivalist is some guy from the army who got stranded in Zion, and he lived through all this crazy stuff, and it's just his logs and his life. Run with it.' It's not really a formal quest. It's just this sequence of learning about this guy's life, and I've seen a ton of people who are like, 'This is the best thing I read in Fallout: New Vegas. I love going through the story.' It's actually very simple because you're really just going from cave to cave and picking up these things, but the story it tells is very compelling, to learn about how this guy went through his life and came to peace with himself when he died."

Lonesome Road, for its part, brought back another would-be companion: Ulysses. It was intended to bring the story full circle by answering some of the questions introduced during the first moments of the game. It was also meant to serve as a dark reflection of the Courier's own story, suggesting what might have happened if everything had gone wrong.

"Lonesome Road was purposely built around the final image at the end of Fallout 1: the Vault Dweller walking off into a lonely future. The idea of a protagonist whose home is lost to him, walking off into the wilderness after helping to nurture and protect a place that ultimately exiles him (or where he simply no longer belongs) is one of the hallmarks of Fallout," Avellone told GameBanshee.

"The sense of abandonment and the lone wanderer connection was important in Lonesome Road, except you're not walking into a lonely future, you're walking into your character's past and seeing what it's done in the present. Ulysses hints that it's possible the player left the West and left NCR because he didn't belong, and that's why he walked the road to the Mojave-but that's Ulysses' perspective, and the motivations for your character are your own."

While New Vegas' DLC wasn't for everyone—plenty of fans and critics consider Bethesda's Point Lookout and Far Harbor to be the gold standards of Fallout DLC—it does find modern day Fallout at its most interesting and experimental.

It was also a rare opportunity for Obsidian to put an exclamation mark on the series. Not many studios get a four episode arc of DLC to close out their game. Obsidian got their chance, and they seized it.

From Cult Favorite to Undeniable Classic

Fallout: New Vegas was seen as a bit of an oddball at release, but a few major factors managed to turn the tide and get people to appreciate its idiosyncracies.

First, it was available on PC, pretty much guaranteeing a long life after release thanks to the modding community. There are hundreds of mods out on the Internet, from texture packs to an attempt to turn Fallout: New Vegas into a multiplayer game, all of which have helped to keep New Vegas fresh. Even Sawyer himself has put out a mod that makes the base game more challenging by tweaking progression and other factors, which he says was a matter of practicing what he preaches (it's pretty much the only mod that he uses when he plays).

"I will say that Bethesda's tools are incredibly good, like just... Straight up, the G.E.C.K is very powerful," Sawyer says. "I think that when I hear gamers who try to pick up a mod of it and complain about it, like, 'You have no idea how bad development tools can actually be.'"

Mods were ultimately an essential component in Bethesda's recipe for success, and Fallout: New Vegas was no different.

Second, with the complaints about the technical side of the game having long since subsided, fans can properly appreciate everything Fallout: New Vegas has to offer. And Fallout: New Vegas offers a lot. From the quests, to the writing, to callbacks to the days of Black Isle, New Vegas is one giant rabbit hole for fans.

Finally, Bethesda released Skyrim, and later, Fallout 4, which invited fans to draw direct comparisons with Obsidian's work. Those frustrated with getting railroaded into one faction or another found relief in Fallout: New Vegas. The stark contrast wound up boosting Obsidian's profile considerably.

You could really see the narrative turn after Fallout 4, which remains quite divisive among fans. Aside from its more robust reputation system, there are the little things, like the fact that you can kill pretty much everyone except Yes Man (who will continually revive himself) and still finish the game. In Fallout: New Vegas, freedom wasn't limited to its vast open world.

While Urquhart won't call out Bethesda specifically (they have relationships to maintain, after all), he does feel strongly that the intelligence of gamers should be respected. "They don't want to be overwhelmed, but that doesn't mean you can't lead them down the road of enjoying a complex system."

That is one of Fallout: New Vegas' guiding principals, and perhaps one of the biggest reasons that it has proven enduringly popular.

Obsidian has since moved on to other projects, but there are still daily requests for a sequel to Fallout: New Vegas. Earlier this year, fans were absolutely certain that a sequel to Fallout: New Vegas set in New Orleans was about to be announced, but nothing materialized.

Urquhart insists that nothing is in the cards right now, "Like we were saying, it was so awesome to get to do Fallout: New Vegas and it was sort of like this is maybe our only chance. If ever it were to happen that we would work on another Fallout, we would absolutely talk to Bethesda about it and think about it, but at this point in time there is nothing on the table where we would be working on another Fallout."

Disappointing, perhaps, for fans of the series. But even if Obsidian never makes another Fallout game, Fallout: New Vegas will live on. They got the opportunity that they could scarcely imagined having when they first started: the chance to make their dream game. The result was a game that many consider an all-time classic.

And seven years after its original release, that's more apparent than ever.