The Lost Child of a House Divided: A Sega Saturn Retrospective

20 years ago, Sega created a beast of a console... unfortunately, the wrong beast for the wrong time.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

Sega Saturn embodies the very concept of "cult favorite." Despite being a major system by one of the three biggest console manufacturing presences throughout the '90s, it sold less than 10 million units around the world — only a fifth of which sold through in the world's biggest gaming market at the time, the United States.

A commercial flop in America, the Saturn trailed distantly behind Sony's PlayStation and even failed to surpass Nintendo 64 anywhere except Japan. Few properties that debuted on Saturn continue to exist as franchises in the modern era. The staggering financial losses the Saturn incurred helped hasten demise of its successor, Dreamcast, and pushed Sega out of first-party status as the new millennium dawned.

Objectively speaking, Saturn was an unmitigated disaster, the keystone Jenga block that sent a 60-year video gaming legacy crashing down. And yet, somehow, this wreck of a platform, this destroyer of empires, commands a legion of die-hard fans — many of whom never owned the system during its natural life span, and many of whom aren't even particular fans of Sega. What is it about this troubled console that makes it more than just a footnote in game history? And how did something capable of inspiring such loyalty go wrong in the first place?

An uneasy peace between nations

Saturn's turbulent life and unceremonious demise did not happen in isolation. Its failure to catch on in the U.S. and inability to outperform Sony's PlayStation both resulted as a side effect of Sega's long, divided history, the fractious relationship between its Japanese and Western arms.

"It's hard not to see the Saturn's failure as a failure of management more than anything else," says Sega enthusiast and game writer Mike Zeller. "By most accounts, Sega's Japanese and American branches butted heads over nearly every issue, to the ultimate determent of the console."

There is no small irony in Sega's internal schism; in theory, no game company should have been better prepared, historically speaking, to find a harmonious balance between East and West. The company, established by American David Rosen in 1940, got its start in Hawaii but moved to Tokyo about a decade later to establish a foothold as Japan rebuilt its economy in the wake of World War II. It was eventually purchased by American media giant Gulf+Western, then bought out by an international consortium that included both Rosen and Japanese investor Hayao Nakayama, who reputedly bankrolled Sega's tenure as a first-party entity.

Yet outside of international arcade hits like OutRun, After Burner, and Golden Axe, Sega could never seem to get its business to line up between regions. The Sega Master System/Mark III saw massive success in Europe and Brazil and moderate popularity in the U.S., but it was a non-starter in Japan. Likewise, the Genesis/Mega Drive dominated America and Europe through the first half of the '90s, but it landed with a dull thud in its home territory.

According to Director of Necrosoft Games Brandon Sheffield, "The goals of [Sega's] Western and Japanese offices were very different. The US and UK offices are what made the Genesis a success. It was much more successful here in the West than it was in Japan. But when the Saturn came out, Japan was back in control — they really cared about this one, so they wanted to dictate things a bit more."

Sega's internal struggle had made itself manifest long before Saturn launched in the company's bizarrely uncoordinated attempts to define a successor to the Genesis. "The decision to launch the 32X (favored by the American branch) and the Saturn (favored by the Japanese branch) so close together only served to siphon sales from both pieces of hardware," says Zeller. "It really started to foster the idea in the minds of consumers that Sega didn't stand behind its consoles and would make whatever decision would net it a quick buck, regardless of how that screwed over early adopters."

"The decision to launch the 32X and the Saturn so close together only served to foster the idea that Sega didn't stand behind its consoles and would make whatever decision would net it a quick buck, regardless of how that screwed over early adopters." — Mike Zeller

This same conflict began to hurt Saturn right out of the gate. Sega announced at E3 1995 — a late spring event — that its Saturn would be available at select retailers immediately, not in September '95 as previously announced. This precipitous maneuver, likely a panicked response to Sony's strong start with the PlayStation overseas, gave Sega's new machine a several-month lead over PlayStation in the U.S. Unfortunately, Sega let the competition have the last word at E3; in its own press conference the following day, Sony's entire message consisted of the system's price at launch: $299, $100 less than Saturn. Sega, having already released its machine into retail channels at a higher price, found itself unable to make a graceful countermove.

"The decision to have a 'surprise' launch for the Saturn in the U.S., mandated by Sega's Japanese branch to the protests of its American branch, [lost it] four months of building hype, which most certainly would have improved its early sales... not to mention cost it most of its third-party launch titles," says Zeller. "Perhaps most damaging to its long term prospects, though, was the way this upset numerous retailers who had been left out of the loop and made them hesitant to do business with Sega in the future."

These conflicting choices and confusing decisions didn't go unnoticed by customers, who grew increasingly wary of Sega's apparent lack of respect for their needs and money.

"Sega lost credibility with its fans," says German game writer Thomas Nickel. "I should know, I was among them. Sega seemed headless, without direction. There's no doubt the whole 32X affair was a major catastrophe and should never have happened. On the other hand, Sega of Japan dropping the Mega Drive [Genesis] so quickly was also a big mistake."

"I see it as similar to the battles NEC went through with the TurboGrafx," says Pulp365 reviews editor Matt Paprocki. "A stubborn Japanese side who believed they understood the American market better than the American side. Why else would most of the best and memorable games sit in import limbo while the U.S. side was granted non-classics like Congo or an updated Corpse Killer? It was a one-sided culture battle."

Bigger in Japan

And so it was that Sega effectively ensured Saturn's failure in the west. Sega of America's president during the Genesis era, Tom Kalinske, had been granted considerable latitude to market Sega's 16-bit console as he saw fit. Even when the Japanese office strongly disagreed with Sega of America's moves — the aggressive marketing, the inconceivable decision to give masterpiece Sonic the Hedgehog away for "free" as a pack-in title — they ultimately deferred to his experience and understanding of the American market.

His efforts paid off; under his stewardship, Sega of America multiplied its profits many times over. Yet throughout the 16-bit era, Sega's Japanese leadership slowly but steadily eroded Kalinske's autonomy, and the early Saturn launch happened despite his protests.

"It always felt that Sega tried to distance itself from its success in the 16-bit era," says Nickel. "Hardly any famous [Genesis] brand was continued on Saturn. Of course, I'm not sure if a polygonal Streets of Rage would have done much good, and a 3D Sonic would have to have been outstanding to stand any chance against Mario 64. But still, with a better mixture of classic brands, new properties, and the great arcade ports, Sega might have at least stood a chance against the Nintendo 64. Saturn's western-developed games always seemed to try a little to hard to seem cool and edgy, while PlayStation seemed to pull coolness off without much effort."

"The Japanese Saturn has one of the most eclectic, creative game libraries of any console, ever," says Zeller. "Its U.S. library is frankly pretty anemic, and outside of a few gems that now, on the secondary market, cost as much as a year of college tuition, most of those games have not aged very well. When third parties saw the Saturn's U.S. struggles, combined with the breakaway success of the PlayStation, it made most of them very reluctant to bring their Japanese masterpieces stateside, leaving countless amazing titles stranded on the other side of the Pacific."

Kalinske left the company a year after Saturn's bungled launch to be replaced by Bernie Stolar. Stolar had just helped usher PlayStation to a stunningly successful American launch, thanks in large part to an excellent marketing campaign that positioned the machine as a futuristic device for adult gamers, but even Stolar's sense for his audience couldn't turn around Saturn's fortunes.

"Sony's marketing trumped Sega's while smartly courting an audience who may have stepped out of gaming for a bit," says Paprocki. "Demographics matter. There was something new to what Sony was doing, more than just releasing their first console. Then there were those who were burned by the unholy console fungus of the Genesis, Sega CD, and 32X – the Saturn wasn't moving in different directions from what was established, and there was zero consumer comfort in a system not backwards compatible with those units.

"And really, it was a change for the industry. 3D was new, it was hot, and Sega bet wrong in their design. Their competition knew it, too. Steve Race's famous 1995 E3 address where he stabbed Sega in their financial heart by announcing PlayStation as a $299 console compared to the Saturn at $399? That's the killer, right as Sega tried to be hyper-aggressive with the immediate launch."

"If recent interviews are to be believed, the U.S. arm of Sega was not ready to launch in May of '95, and what happened in the following months seems to be proof of that," says former Electronic Gaming Monthly editor and Generation-16 creator Greg Sewart. "The early launch put the Saturn in a hole that almost no system would have been able to climb out of — alienating retail partners, throwing off schedules for third party developers, and a dearth of software during the first six months that only furthered Sega's already terrible reputation for releasing hardware without supporting it.

"If that was truly the result of pressure from Sega of Japan, then you have to say that the culture clash lead directly to the failure of the system in the west."

It definitely didn't help that Saturn, in addition to being badly launched, also suffered from hardware design as ill-considered as its launch. Sega found itself caught inexplicably off-guard by the industry's shift to 3D graphics; despite being a pioneer in polygonal game technology with Virtua Fighter and Virtua Racer, the company designed its 32-bit console as a sprite-pushing powerhouse. When the profoundly powerful 3D-capable nature of the PlayStation and Nintendo's "Ultra 64" became evident, Sega's designers hastily added a second processor to the machine, increasing its potential power... but creating such a complex, poorly documented architecture that few developers could hope to tap into the system's true power.

"The hardware was difficult to develop for," agrees Sheffield. "Like the PS3's SPUs, the Saturn's multi-processor setup was theoretically powerful, but it was hard to work with in practice. On top of that, Sega hadn't predicted the importance of 3D in the upcoming console wars, and while the Saturn was capable in this regard, the hardware was under-documented, and used quads instead of triangles like the PlayStation did. This meant ports were difficult, and developing for the Saturn required different and specific skill sets — nobody wants to invest in that when a console doesn't launch amazingly well, as was the case with the Saturn.

"It was a change for the industry. 3D was new, it was hot, and Sega bet wrong in their design. Their competition knew it, too." — Matt Paprocki

"If somehow, magically, the Saturn were the most popular console of that era, there's a remote possibility that quads would've become the standard instead of triangles. PC developers were mostly pushing triangles, but nVidia invested in quads. It could have happened! And it's minor, but Sega's continued lack of support for native transparency in its hardware made all its games look just a bit older and less impressive than games on the PlayStation.

"So then there was the marketing, and the launch. Obviously, Sega's gambit of releasing the console several months early failed hard. There weren't enough games ready, third party developers were alienated because they weren't informed, retailers felt snubbed, and the supply was constrained. They wanted to beat Sony to market, but the only thing they beat was themselves. The third party games that did start to trickle in from Western developers were largely not so exciting, and very PC-like, which felt strange on console. I like Amok because it uses voxels for its environments, but did we need it on the Saturn? Probably not.

"The software was eventually excellent, but by then it was too late. If the system had launched with a larger lineup, a bit later, other developers might have been encouraged to put their A-teams on the job. As it was, Western developers flocked to the much friendlier upstart in Sony's PlayStation. In terms of the hardware, it's not so anemic as people think. Check out the early demo of Shenmue on the Saturn to see what it was capable of."

Once upon a time (not in America)

"I remember seeing the Panzer Dragoon and Nights demos at Best Buy," says Saturn fan Kevin Bunch, "but other than that, I never physically encountered a Saturn, and found those demos to be completely bizarre experiences anyway. I do remember being fascinated by coverage of Fighters Megamix in the gaming press at the time, and was absolutely stoked for Sonic Xtreme. It was all moot anyway, though — by the time I could afford any of that generation of consoles, it was late 1997, the Saturn was already on its last legs, and I had gone with the N64."

The writing was already on the wall for Saturn in America by the time Stolar took charge. Rather than try and salvage the flailing system the way competitor Nintendo has occasionally managed to do, Stolar decided it would be best to cut Sega's losses. By the end of 1997, software releases slowed to a trickle. By summer of 1998, Sega released its last few Saturn games, including the beloved Panzer Dragoon Saga. By the end of the year, just as the generation was truly coming into its own with revolutionary releases like The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time and Metal Gear Solid, Saturn saw its final official release: Working Designs' long-delayed Magic Knight Rayearth, a humble-looking 2D Zelda clone released at the beginning of the system's life in Japan.

Meanwhile, the system continued to thrive in Japan. Though it never came close to the sort of success Sony had with PlayStation, it maintained respectable support through 1999 and into 2000 — well into the Dreamcast's life, which kicked off in Japan in Nov. 1998.

The Saturn's durability at home, along with its friendliness toward developers who weren't quite ready to give up on classic 2D game styles, resulted in a respectable library. Ultimately, nearly 600 official releases saw the light of day on Saturn, about twice as many as were released globally for Nintendo 64. But less than half of those games made it to the U.S., and Saturn is generally most beloved among people who have ventured into the import market. The system's short life in the U.S., not to mention the U.S. market's eager embrace of 3D graphics, left many of the system's best games stranded overseas.

Badr Alomair, a Saturn owner, admits to being part of the problem at the time: "Back then, what I wanted out of the Saturn (well, what sold me a Saturn really) was these types of impressive and immersive 3D games. But the Saturn quickly ran out of those a year or so in. And I sort of ran out of things to buy. I ended up having to buy not-so-great games like SEGA Touring Car Championship or Steep Slope Sliders because the rest of the Saturn library consisted of 2D games that I thought were 'old.' I remember going to my cousin, who also had a Saturn, and thinking, 'his Street Fighter Alpha is just not as cool as my Battle Arena Toshinden' and other embarrassing thoughts. Once Metal Gear Solid came out on the Playstation, I jumped on board and never looked back."

"Seeing Virtua Fighter and Toshinden, or Daytona and Ridge Racer, side-by-side didn't help with the Saturn's image as a system not terribly suited for 3D," says Nickel. "In terms of marketing, Sega seems to have lost a bit of edge. While the PlayStation was perceived as cool, especially in Europe, Sega came across as rather clumsy.

"A more diverse software-line-up consisting of old brands, new IPs and arcade-ports would have been nice — if only to make former Genesis players feel more 'at home.' Without these, the Saturn often felt a bit alienating, strange — not very Sega. At least not very 'Sega of the Genesis era,' anyway.

"While the PlayStation was perceived as cool, especially in Europe, Sega came across as rather clumsy. The Saturn often felt a bit alienating, strange — not very Sega. At least not very 'Sega of the Genesis era,' anyway." — Thomas Nickel

"Virtua Fighter 2 showed that Saturn could go head-to-head with the PlayStation, at least in the first years, if the programmers really understood the machine. The 2D was often amazingly beautiful and the controller was perfect for fighting games."

Sega clearly sensed the uphill battle Saturn it would face once consumers beheld the slick visuals of the PlayStation. Their response: Obscure the games, hide the visuals, and best Sony at being oblique and cryptic. PlayStation's "U R not e" campaign was strange, but Saturn's ads were downright bizarre. Off-puttingly so.

"The marketing...yikes!" muses Sewart. "Sega's marketing took such a weird turn when the Saturn was launched. We went from the quick cut, cool, absurd Sega scream/Welcome to the Next Level campaign to the bizarre and kind of disturbing Theater of the Eye campaign. It was just too weird. Seeing dudes in conehead caps drooling into camera did not really create a great image of the new hardware."

"I owned a Saturn but it was an 'inessential' console in my life," says Wired contributor Daniel Feit. "I bought games for it, often played it for hours at a time, but when I think of the major games that affected me in that generation, they're all on N64 or PlayStation.

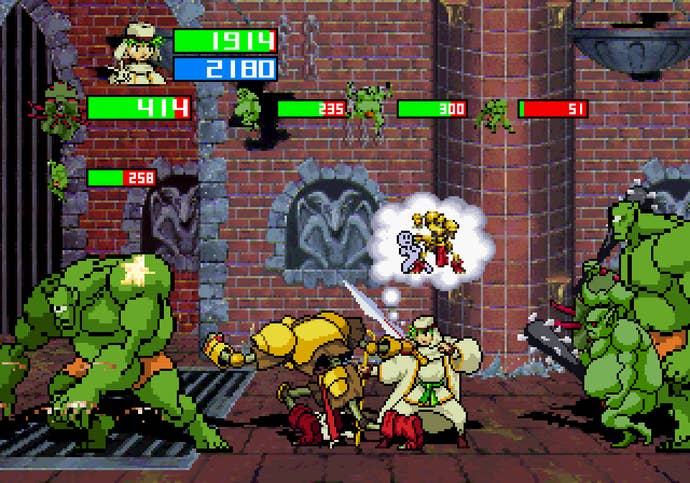

"Primarily I used Saturn to play arcade ports, because for whatever reason the Saturn versions always felt more authentic. Games like Street Fighter Alpha 2 and NightWarriors had more animation and better special effects on Saturn than they did on PlayStation. I also thought the world of the heavy-duty joystick I had for Saturn, which may or may not have been an official Sega product."

Saturn fan Kevin Bunch agrees. "I really appreciate the strength of [Saturn's] '90s arcade conversions, at a time when its competitors were either underpowered or underutilized in that regard. It has without question one of the best libraries of shooters and fighting games out there, and a fair amount of weird Sega titles like Burning Rangers and Nights to fill in the gaps. And really ambitious ideas — the idea of splitting Shining Force III into three separate releases, plus a premium disc, kind of foreshadowed their ideas for Shenmue, for sure.

"I do wish it hadn't fallen prey to internal politics so badly, though. Sonic Xtreme is an obvious example of something that shouldn't have died, but canceling Eternal Champions 3 so it wouldn't compete with Virtua Fighter 2 is just idiocy. There was also the questionable decision to leave those Capcom ports in Japan with the RAM cart, but considering the Saturn's market position and sales, I can kind of understand that one."

"The Saturn was great at pushing sprites, and with its RAM expansion, it could go even further," says Sheffield. "And the fact it was very similar to the ST-V arcade board theoretically meant lots of easy ports — unfortunately, support for the ST-V wasn't incredibly strong, but it was a good plan, that was pushed further with the Naomi/Dreamcast pairing.

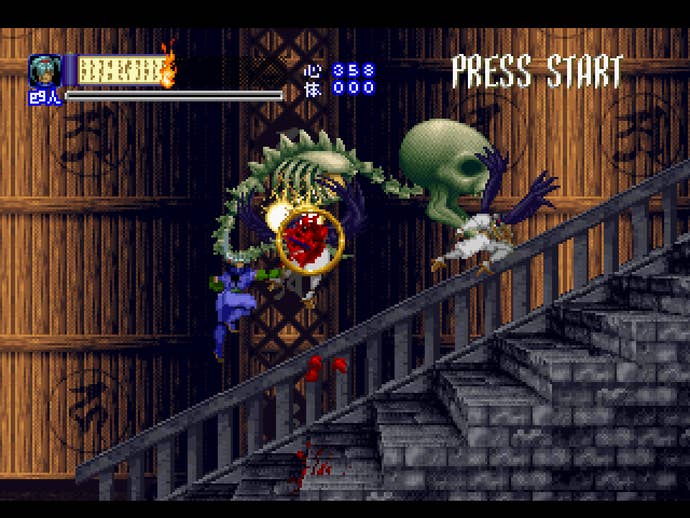

"And back then, Sega attracted a different breed of developer. Games on the Saturn were weirder than those on the PlayStation, and certainly weirder than anything on the N64. There was a lot more experimentation back then, something I really strongly associated with Sega, especially in the titles it developed and published. Sega had a great arcade division, in terms of development. On the console side it was weaker (with some big exceptions, like Sonic Team and Team Andromeda), but very strong as a publisher.

"The Saturn was a landing point for games that were too 'adult' in content for other systems, as it was the only one that allowed an 18+ rating for content in Japan. While most of this resulted in anime fanservice pandering, some games, like Enemy Zero used it to take body horror to new levels, an important step toward the expansion of games and who they served."

The system we deserved, but not the one we needed

In other words, amidst the muddled marketing and bungled business that benighted Saturn, the console itself offered much to appeal to gaming enthusiasts. Its beefy processors offered a glorious refuge for developers who still dealt in 2D visuals, delaying (if not preventing) the disappearance of countless Japanese game studios who thrived during the 8- and 16-bit days. And while its 3D graphics rarely stood up to those of PlayStation and Nintendo 64, it still offered sufficient power that talented developers could create immersive, atmospheric worlds for gamers.

"The Saturn did quite a lot well," says Sewart. "Obviously it was a beast when it came to 2D games, but I don't think its reputation as a weak 3D console was deserved. I think that perception grew out of the fact that the system was just too hard to program for. Couple the difficulty of wrangling the system's power with its ever-decreasing market share and it makes sense that most third parties could not justify the resources no doubt required to make the Saturn sing in 3D. But games like Sega Rally, Virtua Fighter 2, Burning Rangers and Panzer Dragoon prove that system was more than up to the task."

In fairness, though, Sega's inane corporate strategies definitely put Saturn off on the wrong foot — but it's hard to imagine a scenario in which a system geared toward 2D, sprite-based visuals could have triumphed as gamers' tastes rapidly shifted to 3D. Saturn was an impressive console, but its strengths were best suited to a bygone era; it embraced a future that never happened.

"Sega could not have beaten Sony," speculates Nickel, "but they might have stood a chance against Nintendo if they had played their cards a bit smarter. Still, I think the industry's move to 3D and the lukewarm reception to pretty much every 2D game in the second half of the '90s made it quite difficult for Sega. Even if they had released the smoothest, most colorful 2D Sonic imaginable, the press would have complained about it being old-fashioned, and most players would have agreed."

"The war was theirs to lose," says Sheffield. "They knew the PlayStation was a bit stronger graphically, but they made the wrong choices in trying to combat it — rather than explaining what their hardware could do well, they decided to just jump the gun and cross their fingers. Releasing the console later with more games would have been a good start. Better documentation would have helped as well.

"We would've had to start with both of those things in place to even begin to speculate, because without that, you still wouldn't have developers wanting to sign on in the West. There's plenty we could say about Sega not bringing out all the best titles in the West, but by that point, and without a solid customer base, how much would it have helped?"

While all of these factors did Saturn no favors at the time, the combination of a widely deprecated platform and tons of top-quality software (much unseen in the west) give the system a retrospective appeal. Both the press and the gaming public generally ignored or derided the Saturn, which tended to put a hefty chip on the shoulders of its few enthusiasts. Time has softened perspectives on both sides, though, and now classic game enthusiasts tend to regard Saturn as a fascinating counterpoint to the more popular systems, packed with creations that march to a different drum than the popular hits of PlayStation and N64, similar to the relationship indie developers have with AAA software today.

"Saturn was a beast when it came to 2D games, but I don't think its reputation as a weak 3D console was deserved. I think that perception grew out of the fact that the system was just too hard to program for. Games like Sega Rally, Virtua Fighter 2, Burning Rangers and Panzer Dragoon prove that system was more than up to the task." — Greg Sewart

"I admit, I do have a heart for the underdogs," says Nickel. "The Saturn is a system I still like to fire up today for a session of Daytona, Panzer Dragoon or Shining the Holy Arc. This is becoming less frequent, though, as many of the great titles are available in more comfortable form today. Many great Capcom fighters are on PSN or XBLA; Sakura Taisen is out on Dreamcast and PS2; there are many ports of the great Treasure games... still, a few games I really, really loved remain Saturn-exclusive to this day."

"Saturn-era Sega were very generous with content," says Sheffield. "There was always more. There were always secrets. There was always something to find. In NiGHTS, there was an entire enemy-raising simulator built in that was easy to ignore, and many players never saw. Likewise, while the main game was about speed and precision, if you chose to ignore the game's main prompts, and just walk around the world as a child, you'll see areas you could never otherwise access. Sega always made sure its worlds were full, and then invited you to explore, without forcing your hand.

"There were some fantastic new experiences to be had on this console, and it's very sad to me that it had to fail so spectacularly. They just didn't have the positioning to capitalize on these excellent games, because they stumbled out of the gate, and the market was just too crowded to support three major players. We learned this for a fact in the next generation, when, in spite of all the ingredients for success in place, the Dreamcast couldn't turn Sega's fortunes around."

The old shape of things to come

"In the end, the Saturn might be more of a cautionary tale," muses Nickel. "Don't alienate your user base, don't lose focus, don't treat your own regional offices as enemies, don't abandon everything that made you successful before. And if it becomes clear that you won't beat the new market leader, don't abandon all hope. Hang in there, please your remaining user base with good games, and the games that they really want."

Sheffield agrees. With the benefit of hindsight, Saturn predicted many of the troubles that lay ahead for the Japanese games industry as a whole in the subsequent decade.

"I would pose that Saturn's largest legacy is Sega's hubris," he says. "They thought they were invincible, and that structure and hierarchy were necessary for their survival, but more flexibility, and a greater participation with the West could have saved them. This pattern has been repeated with company after company in Japan, and that's how we win up with the Japanese game industry we have today, where you can walk around the Tokyo Game Show floor and find nothing of note to speak of."

"In some ways, the Saturn is a relic, but an important one, which represents the harshness of progress and what it can leave in its wake," says Paprocki. "The Saturn is a comfortable curiosity, with jagged polygons and scornful draw-in, but it has a charm which, like the 3DO, it can claim as its own. No other systems pushed such abstract (and inconsistent) style during the period. You see something in the Saturn and its identifiable surrealism, whereas the PlayStation feels almost sanitary with its heavy push for realism. It was cool and “in” at the time. In retrospect, the Saturn is infinitely more interesting when considering the period during its lifespan."

"The Saturn was an interesting transitionary console for me," says Sheffield. "You've got the 'Blue Sky in Games' Sega in full effect, with games like Daytona, Virtua Fighter, and others, but you also had a darker Sega showing more of its teeth. Burning Rangers and Panzer Dragoon Saga are excellent examples of the slightly more unnerving side of Sega. And NiGHTs Into Dreams was right in the middle — the hopeful dreams of Nights, and the nightmares of Reala."

"Unfortunately. the system's legacy in North America will always be the hardware that ruined Sega," says Sewart. "It will always represent Sega of Japan wrestling power back from Sega of America, the complete opposite of what seemed to happen five years earlier with the Genesis.

"For me it represents all of that. But it also represents the sort of amazing library that was possible due to Sega finally succeeding in Japan. It's also my first memory of playing a console game online, as well as the first console where I actually imported games. It's a pity the Saturn's legacy is so shameful, because its library is actually quite impressive."

Saturn's place in history is difficult to define in large part because the system was neither the beginning nor the end of the troubles the resulted in Sega's demise. It was a point on a timeline that began with the company's power struggles and fragmented hardware strategy in the 16-bit era and ended with the Dreamcast, a system born from a competition between America and Japan that squandered countless millions of R&D dollars. Saturn didn't instigate Sega's departure from the hardware market; in many ways, it was more a symptom of that breakdown than a cause.

Zeller, though, frames Saturn's place in history most eloquently. "I feel like the Saturn's legacy is really twofold," he says. "For Sega, it was definitely the final nail in the coffin of their hardware development. They absolutely learned from their mistakes, as everything they did wrong with the Saturn they did right with the Dreamcast, but it didn't matter. Coming on the heels of the questionable Sega-CD and the disastrous 32X, the way the company continually bungled everything to do with the Saturn not only convinced consumers (and a lot of developers) that Sega had no clue what it was doing with its hardware. It also allowed Sony to take a massive lead in the console race, both in terms of finances and mind shares.

"The Dreamcast was a pretty great console, but consumers were extremely wary after the Saturn debacle. And besides, why would they want to take a risk on Sega when they had the surefire hit PlayStation 2 coming out just six months later? Ultimately, Sega's internal bickering undid not only the Saturn, but their hardware future as well.

"The other, somewhat brighter piece of the Saturn's legacy, is that in the years since its untimely demise it's become something of an El Dorado for classic game collectors and importers. Stripped of the corporate baggage that hung about its shoulders at the time of its release, the system stacks up well against both its contemporaries and classic consoles as a whole.

"No other console released in the U.S., with the possible exception of the TurboGrafx-16, has ever had such a massive portion of its library, including most of its best games, left un-localized. As such, adventurous and/or bilingual gamers have made all sorts of amazing discoveries among its Japanese games. All the amazing RPGs may present a bit of a language barrier for those of us who don't speak Japanese, but the legion of fantastic shooters, fighters, and other arcade-style games that called the Saturn home are a cinch for monolingual importers to enjoy."

In other words, the Saturn represents an inviting video game frontier for adventurous gamers: A piece of game history, one of which Americans saw only a tantalizing fraction. Difficult to emulate, with a library that even today is incompletely chronicled in English, Saturn's hidden treasures — along with its better-known but inaccessible greats — simply beg to be discovered.

That's hardly the legacy a system with as much heritage and as rich a creative library as Saturn deserves. Ultimately, though, the system's failure has less to do with its hardware or software than with corporate decisions surrounding its life. Though Saturn diminished Sega's potential as a major industry player for the future, on the other hand it offers a rich and worthy piece of the past.

Image credits: Wikipedia, Hardcore Gaming 101, VG Museum