The Last of Us TV show is doing one thing very differently from the games – and I love it

In moving from game to television, HBO had to make some things more realistic – and it benefits the show a lot.

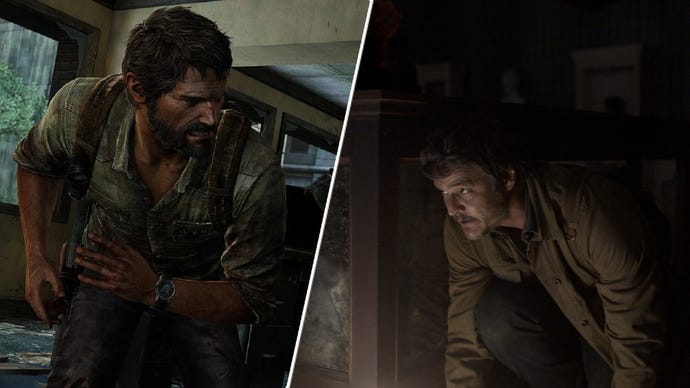

If you’ve played even the first few hours of The Last of Us – you know, like you can do totally for free on PlayStation right now – then you’ll know one thing about Joel. He’s a squatter. The gruff murder dad must have thighs like wrought iron. Whether he’s trying to avoid the sharp hearing of a Clicker by crouching and moving softly through a ruined library, or he’s hunkered down to get out of sight of some p**sed-off FEDRA recruits, the man likes to squat.

But it’s not realistic, is it? When was the last time you spent upwards of 20 minutes, in the p**sing rain, hunkered down on your haunches, waiting for your opportunity to garrote some harder-than-nails security guard? Probably never. Even a quick skirmish in a paintball arena – or some cheap, local run-down laser tag set-up in a forgotten industrial estate nearby – will show you that crouching and moving like that for even a few seconds is murder on the legs.

In the game, that’s the bulk of gameplay: it’s a stealth survival game, after all, and staying out of enemy sightlines and remaining quiet is essential if you want to keep all your limbs intact. Joel is no spring chicken, either. He’s 55. I’m 31, and can barely stay hunkered down for a minute without my back crying with a million muscle spasms and my spine noping out on me. Granted, Joel has probably had a few more cardio sessions in his recent past than I have (running from something infected with the Cordyceps brain infection will do that for a guy), but you can’t deny the toll that age takes.

In an interview with Polygon, The Last of Us TV show co-creator Craig Mazin told the site that the show had to make some changes from the game because it needed to look more realistic than the source material. “Joel’s walking in a crouch so much that he would have, like, these massive quads, right?” Mazin explains in the interview. “55-year-olds can’t crouch for more than like three minutes! Tops! And then their back gives out.”

It’s similar to the constant healing that’s present in the game: get shot, get smacked about by the shambling undead, or otherwise mess up your body, and you’ll need to MacGyver some rudimentary medkit together in order to stem the bleeding and get back on your feet. In the show, the threat of violence is frontlined – not the actual violence itself. It wouldn’t make great TV if 20 minutes of every episode consisted of Joel pouring ethanol onto a rag and fingering some pus out of an open gash on his shin.

Making the characters more human – and therefore more vulnerable, and more relatable – is part of what makes The Last of Us such compelling television. Similarly to the game, the stakes are all very human; we’re watching a man act out his healing and his grief in real time, forced to confront the pain that he’s been running from for decades. By making his body as understandable as his mind, the show does a deft job of drawing us in and making us care immediately.

That’s why these first two episodes have worked so well: they’ve established the stakes, the state of the world, and the motivations and starting points of our characters with minimal ambiguity. Even the least media-literate person can watch the show, put the pieces together at this early stage, and have everything lined up nice and neat for the rest of the journey. And little, knowable details, like how Joel can only take one bullet or only ‘roadie-run’ for a few seconds at a time, are integral to establishing and maintaining that illusion.

So far, The Last of Us is up there with some of the best gaming TV we’ve ever gotten – on a scale with the likes of Arcane, Castlevania, Cuphead, or The Witcher. If the series carries on with this momentum, it’s likely it’ll be remembered as one of the very best there’s ever been. Here’s hoping it’s got the legs for it.