The Indie Game Unsuccess Story: How the Creators of The Magic Circle Survived Their Own Gaming Nightmare

When two developers behind BioShock set off to pave their own path, things didn't go as hoped.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

The conventional indie game developer success story goes something like this.

After growing disillusioned in the overly-corporate mainstream, a group of designers and artists take a risk and set up their own studio. Idealistic and humble, the group are finally able to make the game they've always wanted to make, a game that just so happens to resonate with an increasingly sophisticated and artistically aware video game audience. The developers make their money back and then some, win awards for “narrative,” and start to plan a second game—a game that’s going to be even more honest this time. Reassured that low-budget, personal, and idiosyncratic titles can be successful, an entire culture also gets to feel like video games, at last, are getting better by the power of their sheer creative worth. We all agree the independent video game scene is destined to succeed.

As former BioShock developers, Jordan Thomas and Stephen Alexander are familiar with unconventional video game stories. For over six years—first at 2K Boston, later at Irrational Games—they helped redefine what big-budget games could do, invigorating the famously crude shooter genre with horror, tragedy, and political intrigue. Before taking on directorial duties for BioShock 2, Thomas co-designed the original's epochal Fort Frolic level. From sea-water cascading through Rapture’s corridors to neon lighting effects and scary set-pieces, like the appearance of the first ever Splicer, Alexander’s art and visual work had helped set BioShock’s tone. But in 2013, they left mainstream game development to found their creative partnership, Question; like the series that had introduced them to one another, their first independent game was set to examine and test gaming's boundaries.

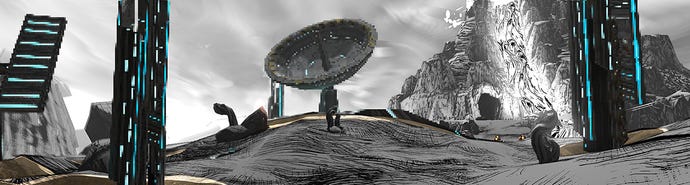

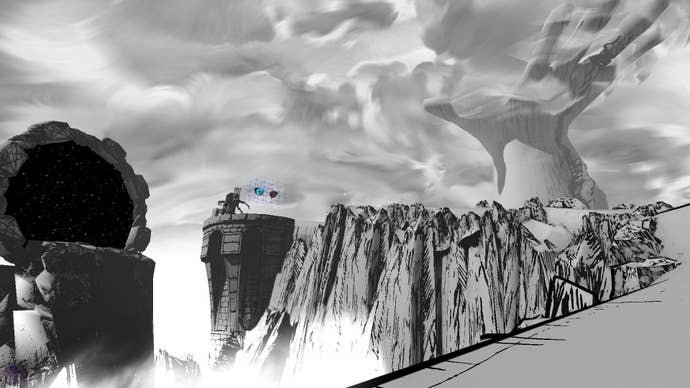

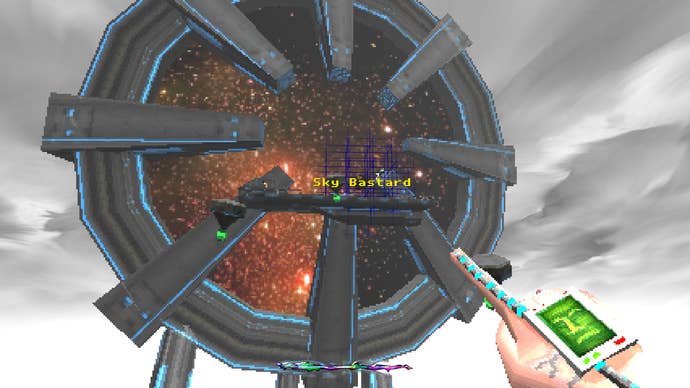

Called The Magic Circle, the game took place inside an unfinished, eponymous fantasy RPG. Directed by an old software bug that had become sentient and gone rogue, players were led to excavate, edit, and ultimately destroy The Magic Circle from within, indicting its creators and their volatile fanbase in the process. It was smart, personal, and unflinching, but contrary to indie game myth, The Magic Circle would not become a hit.

"We thought we were striking while the iron was hot," Thomas says. "What we didn't realise was that the indie wave was about to break."

In summer 2013, after finalising the original concept for The Magic Circle, Alexander and Thomas moved into Question's new headquarters, a house in San Francisco owned by Alexander's parents. The studio had two priorities: cultivate the game's art style and plan its narrative. Work began in earnest. However, given The Magic Circle had to look like an unfinished game with very little colour, basic graphics, and even some missing textures, Alexander started to worry if its pre-release screenshots would be understood as intentional or misinterpreted as genuine. It was possible the game's "sloppy" appearance could put potential buyers off.

On the contrary, sloppiness and roughness were at The Magic Circle’s center. Commercial risk or not, the game had to look a certain way.

"After three BioShocks," says Thomas. "I remember feeling intensely frustrated, both with that 'self-serious' style of games and the various corporate strata that had been bearing down on us. I felt like game development had the same elephant in every room; [that] this is a video game and nothing we’re making here makes sense once you compare it to anyone's real experience. We were constantly making excuses, for example, for the fact [that] our protagonists couldn't talk. The self-serious tone is really set against games' own nature. So with The Magic Circle, I wanted to make something that was more at ease with its own rough edges."

"Making a game like this without any concern at all for its commercial value, after so many years in triple-A, that was very therapeutic. But talk about lack of self-awareness. We were sort of living The Magic Circle ourselves, just in terms of ignoring any blind spots."

To fund The Magic Circle, Thomas and Alexander turned to family, partners and wives: the game lived, as Thomas puts it, by "spousal grace." The duo also hired a third veteran developer. Dishonored gameplay programmer Kain Shin, whom Thomas had first met in the early 2000s, replaced and perfected The Magic Circle's fragile internal systems—most specifically its central mechanic, whereby players could mix, match, and edit in-game assets as if they were designers themselves.

Towards the end of 2013, The Magic Circle had a solid, technical foundation. Its writing and story, however, were subject to a sudden change of direction. What was once a pure comedy in the mock 'making-of' style of Spinal Tap and Swimming with Sharks quickly became much darker.

"After GamerGate started, my attitude towards games and gamers was really put through a mixer," says Thomas. "I tried to put my feelings together again, on the other side, but they'd changed. Everything was changing."

"The role of Coda Soliz, the fan who gets a job on the game-within-the-game and in her mind is going to save it from its own creators, her role darkened a lot. Essentially, this whole wave of pollutants had come to the surface of gaming culture. My friends were getting death threats, and it meant I couldn't see game fans as true innocents any more. In hindsight, this might have made it difficult for people to find any character in The Magic Circle with whom it was easy to sympathise. But I couldn’t unsee all this, even if I wanted to."

Nervous about how The Magic Circle and its burlesque of the gaming industry would eventually be regarded, Thomas and Alexander maintained a degree of allegory. As well as games, gamemakers, and game fans, they discussed narcissism and obsession generally, and tried to find more universal truths. But some of their own experiences made it into the game practically unveiled. The Magic Circle, in Alexander’s words, got "meaner." Through in-game text logs and email exchanges, the pressures of working on a big, modern video game were given voice.

"The in-game conversations between the art and design departments," Alexander continues, "There's only a very thin filter between what’s written there and my own experiences. The nature of that, a team of people who end up fighting just because they care so much, I wanted to represent honestly. Needling the industry, game developers and ourselves, that was always the guiding star. And we basically ignored the idea of making something commercial. But all that stuff, outside forces plus our own desire to make something intensely personal, worked against our chances of big financial success."

In May 2015, when The Magic Circle went into Steam Early Access, all concerns about its commercial appeal came tangibly to bear. Back when the game was originally conceived, indie darlings like Gone Home and Papers, Please had seemed to suggest short, contrarian, and risqué games could make a lot of money. Two years later, something had changed. Critical responses, either from users or the press, were largely enthusiastic; it wasn't like The Magic Circle was shoddily-made, or prohibitively, unprecedentedly niche. Nevertheless, its initial run yielded sales below Question's modest expectations.

"We'd seen big Early Access successes," Alexander says, "But we only sold about 1000 copies. We stayed hopeful, kept making the game better. And the people who'd actually played it were amazing. Talking to them was a wonderful experience, gave me a lot of faith in at least a subset of gamers. But financially, yes, it was an early warning."

The Magic Circle was featured on Steam’s new releases page and briefly listed as a "Top Seller," but its initial numbers quickly tailed off. Whether it was the screenshots pre-release, which Alexander had worried would make the game look unremarkable; the writing, that Thomas knew would be an acquired taste; or something more vaporous, some trend either settling or emerging, it became suddenly clear The Magic Circle was not going to make the money Question had expected.

Certainly, the world awaiting a newly-released, independent game looked much different in 2015 than when Question was originally formed. According to SteamSpy, throughout 2013, 565 new games were published on Steam. In sharp, borderline intimidating contrast, 2969 new games were released on the same platform in 2015. Essentially, within two years, the competition The Magic Circle faced for gamers’ money had increased almost five-fold. At the same time—and in the wake of titles like The Stanley Parable, Game Dev Tycoon, The Writer Will Do Something, Goat Simulator and, ironically, BioShock: Infinite—critical discourse on the absurdity and nature of videogame development had already been picked clean. The Magic Circle found a few rave reviews—and from big publications—but generally it was scored 7s or 8s, which in the arguably skewed language of video game recommendations was not enough to qualify it as a "must buy." At least enough to damage The Magic Circle’s commercial appeal, it seemed like, in the years between its conception and release, tastes had changed.

By 2015, The Magic Circle’s overarching insight that making games is a difficult and convoluted process involving much compromise, perhaps felt less urgent or incisive as it once could have. And in the culture post-GamerGate, it's quite easy to imagine the audience for games feeling one of two things: either that games have let them down and they needed something more uplifting than The Magic Circle's at-times-uncomfortable satire, or that the notion that gaming is fraught, ambiguous, and perhaps ultimately unsatisfying is self-evident, and hardly worth $20.

Today, however, Thomas and Alexander may only speculate as to what factor or combination of factors altered or damaged The Magic Circle’s sales potential.

"People have come to me and said, 'The market screwed you,'" says Thomas. "But we'll never know for certain. What I do know, however [is that] the culture of sales defines Steam. Buying a game at full price, from the perspective of a gamer, that's for suckers. If it's not multiplayer or a show-piece for your latest graphics card, then why buy when it comes out? Gamers' tastes have shifted pretty radically towards experiences that are 'meaning machines.’ Whether because of procedurally-generated or massively-multiplayer games, gamers today hold fire on anything that offers less perceived value per dollar. Obviously, I fiercely disagree with that. If a game can sort of touch my soul in some way in a few hours, I'm so grateful to it. But that's not the guiding principle for a lot of people buying games. Almost all the negative user reviews of The Magic Circle mention length as part of the reason they're not satisfied, so everybody coming to our page reads 'wait for a sale. You can get this for less.' There’s just no incentive to buy on release."

An unfathomable market, fickle players, the battle of attrition to get some thought, some feeling, some substantive point out into the world of games, The Magic Circle had fallen victim to the very things it had attempted to satirise. As if to drive the irony home—to complete the set of developers, fans, and critics being made to look foolish—evangelical reviews at major publications barely affected The Magic Circle's sales. Perhaps in a realer way than was intended, Question had exposed games' raw, difficult-to-look-at underbelly.

"I'm not trying to start any fights," Thomas says, "But the truth is, on the days when a major publication published a glowing review of our game, and we had a few, we barely saw a sales spike. Meanwhile, Jim Sterling published a video of the first ten minutes and we got the biggest sales jump we ever saw."

"Compared to a lot of other games we had a lot of coverage," continues Alexander. "Those articles though, they would come and go within a day, and the people reading them were probably already enthusiasts. Then again, we share the blame. What we chose to make was not an easy sell."

The commercial response to The Magic Circle meant Question had to examine, and in some cases drastically alter, its creative direction. To try and drum up more revenue, a console port of the game became an urgent priority, though this itself invited problems. "The version of Unity we'd used to make it for PC wasn't supported on PS4 and Xbox One," says Alexander. "I had to do a lot of work."

The studio also started to think about its next game not just in terms of what it was going to say or what it would express, but financial viability. Thomas and Alexander had paid off their debts and earned enough to keep Question just about open, just about, but if they wanted to carry on making video games, their next title needed to be more broadly, instantly appealing.

There is a conventional indie developer success story, but it's probably less accurate than it is reassuring. After growing up with parents, peers, and the mainstream press telling us our favorite hobby video games was silly and for losers, it's emboldening to feel able to say, "Actually, games are becoming more artistic." More broadly speaking, it's heartwarming to see that when people quit their jobs to follow their dreams, it all works out; given the world we live in, it's nice to believe that real, artistic energy can simply prevail.

Reality, of course, is more convoluted. Some independent developers make millions. Others do pretty well, break even, or go broke. Video game culture doesn't make straightforward progress toward higher art and things don't unambiguously "get better." No single article, paragraph, or tweet can comprehensively surmise modern video games. There is no all encompassing success story.

Testament to that nuance, Question, despite its tribulations with The Magic Circle, has managed to sign to a publisher, hire two new designers—David Pittman, creator of Neon Struct, and Michael Kelly, formerly of Hangar 13 and 2K—and start work on their next project, an unannounced and still shrouded-in-mystery cooperative horror game. The Magic Circle might have faltered commercially and kept them awake some nights, but Thomas' and Alexander's debut collaboration also provided some answers. Considering why it was made, to clarify conflicts, elucidate disappointments, and to make it clear that no video game story is straightforward, The Magic Circle, by its own misfortunes, could be considered a resounding success.

"We made enough not to be truly embarrassed of the work," says Thomas. "We didn't leave a complete crater. On the other hand, we realised we had indulged ourselves first. A lot of studios make something commercial then indulge themselves later. I've thought many times: could we have done something else? But I feel like, since my youth, I’ve sacrificed myself over and over to this God of Video Games, and a lot of that is represented in The Magic Circle. So I like to think we've cleared triple-A, and with a healed heart."