The History of RPGs: How Dragon Quest Redefined a Genre

COVER STORY: 30 years ago, a small team of Japanese game designers changed the way the world looked at role-playing games.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

A quest begins

By May 1986, Nintendo's Famicom had established itself as the most popular gaming device in Japan by far. The MSX computer fared well thanks to its low price point, and both NEC and Sharp had carved a respectable market for themselves with their higher-end machines. But Famicom was clearly the system to target for anyone who hoped to produce a genuine hit, and so Chun Soft's RPG project would be a console creation. The problem, of course, was that consoles were just as poorly suited for RPGs as they were for text-driven graphical adventures. Fortunately, the solution the duo had implemented for the Famicom version of Portopia made just as much sense for an RPG: A windowed interface with a simple list of commands that players could easily navigate with a D-pad and two buttons.

Between the two men's experience, interests, and expertise, Dragon Quest turned out to be a thrilling hybrid of multiple influences. Like Ultima, it featured a grand world map throughout which players could find towns and dungeons. But its sense of progression seemed to have more in common with Wizardry, presenting a linear curve of difficulty based on the player's location relative to the starting point. NPC conversations proved essential to the experience as well, offering clues and guidance similar to the way the characters in Portopia did. Meanwhile, Nakamura's experience with the speedy action of Door Door helped pare down the game's overall design into something lean and fast-paced compared to other RPGs of the era, yet which didn't compromise the genre's underpinnings to the same degree that action RPGs like Zelda did.

This was, perhaps, Dragon Quest's greatest accomplishment: It compacted the essence of role-playing games into an efficient, no-nonsense format. Where most earlier console renditions of the RPG (and indeed quite a few computer-based adaptations of the genre, such as Falcom's Sorcerian and T&E Soft's Hydlide) went heavy on the action and light on the statistics and inventory management, Dragon Quest pruned excess limbs while keeping the genre's heart intact. Players earned experience as they battled foes, and with each new level to which they ascended, they'd grow both in power and skills, learning new magic spells at fixed increments.

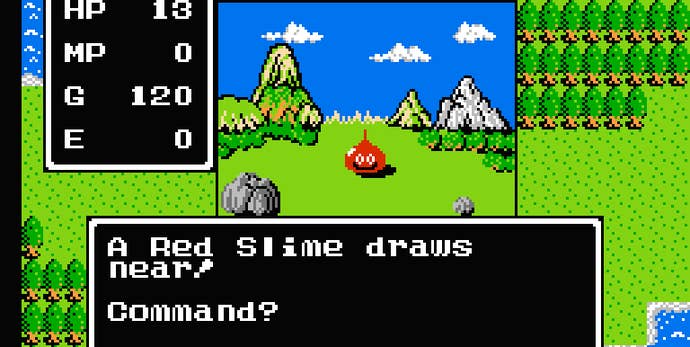

In hindsight, the original Dragon Quest centers around a laughably simplistic take on RPG mechanics. You control a single character; you have only a few quest objectives (save the princess, prove your heroic lineage, gather the tokens needed to reach the Dragon Lord's castle, and defeat the villain); you fight a single enemy per battle; equipment follows a simple upgrade path; and you learn the same handful of spells at the same set intervals every time. The closest the game comes to a class system or character customization is a hidden element of randomization that uses the player's name entry to determine their stat growth at level-ups. Still, fundamental as they may be, Dragon Quest's systems obey the rules and expectations of the era's computer RPGs. Statistics drive everything, with both the hero's and monster's strength, speed, and defensive power determining the outcome — with the help of random modifiers, of course. Dragon Quest demands the player explore the world, challenge ever-stronger foes, and, yes, grind for experience points and cash, the same as any "real" RPG.

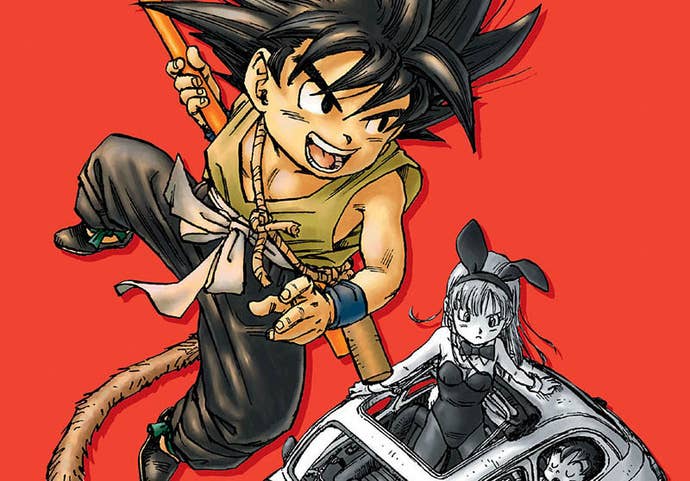

Besides Horii and Nakamura, two other men made essential contributions to the game. Koichi Sugiyama, a well-known screen composer, crafted the game's memorable melodies. And Dragon Quest's look, from its energetic cover art to its battle graphics, came courtesy of the legendary manga illustrator Akira Toriyama. Sugiyama had come into the project through his enthusiasm for Portopia: He wrote a letter expressing his love for the game, which put him in touch with Horii. Toriyama, on the other hand, had been tapped as the game's illustrator more through a business connection; Enix had a close relationship with the magazine behind Toriyama's new series Dragon Ball (as well as its predecessor, Dr. Slump).

While Horii is typically regarded as the creator of Dragon Quest — he continues to serve as an extremely active and highly involved creative lead on the series to this day — for the original game, all four leads played equally important roles. "The scenario, including the map, was created by Horii-san," Nakamura recalls. "And then graphics were drawn by Akira Toriyama, and the music was by Sugiyama-san. But for the original Dragon Quest, the game design and battle system logic were created by me and Horii-san. Both of us would talk about it and exchange opinions and create the core game system together."

Remarkably, the quartet hit it out of the park in their first attempt. While the series has evolved considerably through the years, there's no mistaking the original Dragon Quest as a part of the franchise it spawned. The moment you turn on the console, you hear Sugiyama's anthemic fanfare, which continues to serve as the title screen music for every sequel in various permutations. The first monster you inevitably fight in the game, a grinning blue onion-shaped slime, has become a series trademark.

"Toriyama took all these grotesque Dungeons & Dragons mainstay monsters, and made them adorable," says AGM designer Nayan Ramachandran. "There's something incredibly iconic about the game's visual style. It's insane to me that Toriyama took a monster like a slime and somehow made it into mascot material."

The slime works both as a series mascot — its simple design, basically a ’70s smiley face superimposed on a teardrop, adorns a seemingly endless array of merchandise — but also as a perfect summation of what helped set Dragon Quest apart from the many role-playing games that had come before it. The slime has long been an RPG staple, ever since Dungeons & Dragons gave us the gelatinous cube. They typically serve as low-level fodder, able to inconvenience novice adventurers but posing little real threat, especially once the heroes have a few levels under their belts. Where other RPGs' slimes appear as amorphous blobs, writhing puddles of goo, or mindless bricks of gel, Dragon Quest's slimes are inexplicably cute. They're are harmless as they look — even landing a lucky attack, a slime will never inflict more than 1/5 of a starting, unequipped warrior's maximum hit points — and yield a single experience point and a single coin, rendering them valuable as training fodder only until you earn your first level-up. Yet they continue to appear until the end of the adventure, first as a minor inconvenience that can chip away at the health of a hero wounded in more serious encounters, then eventually as a reminder to a mighty hero capable of taking on the dread Dragon Lord himself where he started from. And then there's the rare Metal Slime that appears fleetingly later in the game, an evasive foe that yields valuable experience points... if you can manage to kill it.

Not all of Dragon Quest's monsters share the slime's cuteness. On the contrary, monsters' mascot appeal follows an inverse curve in relation to their deadliness. The beasts you meet in the early going have a certain adorable quality: Besides slimes, you initially encounter creatures like drakees (grinning vampire bats with chubby spherical bodies) and ghosts (which wear floppy hats and mock the player by sticking out their tongues). As you range further afield from the relative safety of Tantagel Castle, however, the creatures you encounter slowly shed their whimsical look. Wolves and wyverns pack more of a punch, and their expressions appear less guileless than those of the lower ranks — they're smiling, but it's more of a smirk. And then you get to the real challenges: Skeletons who wield wicked broadswords and grin at you with empty eye sockets; axe knights clad in full-body armor and wear a grim scowl on their faces; and mighty golems who loom over players with blank faces save for a pair of menacing glowing eyes wreathed in shadow. Even the final boss himself upholds this dichotomy: He initially appears as a small, almost comical wizard who could just as easily have been one of the early villains of Dragon Ball, but midway through the battle transforms into his true form: A gigantic fire-breathing dragon who conveys his ferocity by breaking the visual design rules of the game. Where every other enemy in the game appears in a small window bordered by the current field map, the boss' final form takes place against stark black, and the dragon extends one of its legs into the game's dialogue box, violating the player's space to make it clear he can't be contained by the same rules that constrained his minions.

The entirety of Dragon Quest was packed with smart little details like this. In hindsight, yes, the original version of the game feels as primitive as you'd expect from a 1986 Famicom release. You need to use specific menus commands to perform actions that would be automatic, or at least contextual, in a modern RPG. There's even a separate command to climbs stairs. And though this was changed in the U.S. release three years later, the hero's sprite always faces out from the screen, adding an extra step for simple actions that already required a menu command — rather than standing next to a townsperson and pressing a button to speak, you instead needed to bring up a menu, choose "TALK," and then press the direction in which you wanted to talk. Yet these minor inconveniences didn't seem so egregious in light of the fact that Dragon Quest not only did something that no one had ever pulled off — bringing a proper RPG to consoles — but did so with aplomb.

As a game, Dragon Quest lays down its rules quickly. You begin in the King's throne room and can't leave until you figure out how to open treasure chests to claim a key and use it to unlock the door to the throne room. Does it make sense that the king would lock an aspiring hero into his inner sanctum? Not at all, but as a tutorial it's brilliant, teaching players to speak to NPCs, make use of menu commands, and apply commands logically to solve simple problems. The king also gives the character some cash to spend at the local shop — enough for players to equip themselves with some basic gear, or with a decent sword and no armor. Tantagel Castle is populated by people who dispense helpful advice before you ever set out to see the world, and it features an enticing mystery (a locked room) that invites players to come back later in the adventure. You can't actually buy equipment until you make the trek from Tantagel to the nearby town of Brecconary, though, so you're forced to make a short journey across the world map. Chances are good you'll find yourself beset by a monster en route... but it'll be a simple slime, a creature you can defeat safely while unarmed.

Later in the player's journey, however, the game begins to break its own rules. Perhaps most memorable is the town of Hauksness, an abandoned city overrun by monsters. Appearing late in the game, Hauksness subverts the rule of thumb that cities offer a safe haven — it contains both random encounters and an optional boss that puts up a more ferocious fight than any other creature in the game besides the Dragon Lord. Hauskness can be a nasty surprise for newcomers, who are drawn to its world map icon in search of sanctuary from the region's deadly monsters only to find a ruin every bit as deadly as the surrounding world. The game's rules and mechanics may be simple and few in nature, but the developers did a remarkable job of parceling them out, and in pacing the appearance of surprises and inversions to keep players on their toes. Dragon Quest's world and the quest within feel small by current standards, but it was fairly par for the course by contemporary standards. The player dealt with a simple succession of tasks. The in-game text walked a fine line between nudging players in the right direction and letting them sort out the tasks ahead on their own. On a console where "save the princess" typically amounted to the goal of most games, the fact that rescuing poor Gwaelin happened halfway through the story (after which she served as a sort of real-time hint dispensary) felt like a creative inversion of NES standards and made the adventure feel much larger in scale than your typical action game. But Dragon Quest did adapt one crucial element of NES action games into its rendition of the role-playing genre: Speed.

Fittingly for a console game, Dragon Quest played out as a much zippier experience than its computer-based forebears. Compared to PC RPGs that could stretch for dozens if not hundreds of hours, Dragon Quest can easily be completed within 25 hours by a newcomer, and in about a quarter of that time by an experienced and determined player. It's not necessarily that the game is vastly smaller than PC RPGs of the time, but rather that it eschews heavy grinding for cash and experience. It also abandons the punitive design of computer games almost entirely.