The Hidden Depths of Otaku Games

Are titles like the upcoming Senran Kagura Burst nothing but fanservicey pandering, or do they offer something more? Pete chats at length with Xseed and NIS America about the more misunderstood end of Japanese video game culture.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

I make no secret of the fact that I'm generally drawn to Japanese games in preference to Western titles -- as, I know from reading many of your comments, are many of you reading this.

My own reasons for feeling this way are manyfold: the games I particularly enjoy tend to have an immediately appealing, colorful aesthetic; they tend to have very strong, well-defined (if often tropetastic) characters; and, in many cases, they're willing to delve into subject matter that more conservative Western publishers won't touch -- not just the more obvious taboo subjects like sexuality and violence, but also topics like depression, self-esteem, finding out your place in the world and all manner of other thought-provoking material. This isn't to say that Western games aren't also capable of this, of course -- many Western titles are, in fact, starting to explore more challenging subject matter, particularly in the independent sector -- but we still have a long way to go.

There's a bit of a problem, though, and it's to do with negative perception from those who aren't already immersed and invested in the culture of Japanese media -- not just games, but also anime and manga, too. To a certain degree it could be argued that Japanese media brings this problem on itself by being unapologetically insular and focused on catering to specific niches -- but at the same time, there's a lot of people out there who don't look at the whole picture and instead settle for a kneejerk reaction based on limited evidence.

From a game perspective, I'm referring specifically to the phenomenon some refer to as "otaku games" -- those experiences that can often look to an outsider like the very worst kind of fanservicey pandering. Generally filled to the brim with big-eyed moe girls, gratuitous panty shots, a strong dose of obvious male gaze and physically improbable breast physics, it's extremely easy to dismiss these experiences as being nothing more than shallow titillation for horny teenage boys. If you're someone who habitually derides Japanese games out of hand for this reason, you are, of course, perfectly entitled to your opinion, but I would at least urge you to look a little deeper into the nature of these experiences before making a decision as to how you feel about them, one way or another.

Unsurprisingly, that's what we're here to talk about today.

I'd like to talk frankly about my own opinions and tastes first of all, then I'm going to share some thoughts that representatives from Xseed and NIS America -- two publishers who specialize in this kind of laser-focused, niche-interest content -- have been kind enough to share with me. Whether or not you've changed your opinion by the end of this piece will, of course, be entirely up to the individual, but if nothing else I hope you'll at least feel a little more well-informed and perhaps justified in your opinions, whatever they might be, by the end.

I've been a fan of Japanese games since Final Fantasy VII -- yes, I know, I know -- but I've only really become strongly invested in Japanese popular entertainment as a whole (i.e. including anime and manga) in the last couple of years. I primarily attribute my interest in this sort of experience to the fan-developed visual novel Katawa Shoujo, which was released onto an unsuspecting world in January of last year.

For those unfamiliar, Katawa Shoujo isn't actually a Japanese game at all; its origins may lie in a Japanese doujinshi artist's sketches depicting girls with various physical disabilities, but the project as a whole was actually developed largely by English speakers. It is, however, very Japanese in its sensibilities: it's set in Japan, stars Japanese characters and makes use of a lot of Japanese cultural norms. It's also fairly representative of the (largely Japanese-developed) visual novel genre in that it's a very character-driven story that doesn't shy away from difficult subject matter, whether that's the nature of the girls' disabilities themselves -- which actually end up being the least important parts of the game's various narrative paths -- or the more deep-seated issues each of them are dealing with. And yes, it includes explicit sex scenes -- though it is worth noting that as in many other visual novels that put story before sex, these aren't designed to be titillating, and in at least one case are genuinely uncomfortable to witness.

After spending more than 40 hours devouring Katawa Shoujo and seeing everything it had to offer, I wanted more, so I started delving into the world of Japanese-developed visual novels that had been translated to English. Along the way, I discovered a variety of different experiences that are now among my favorite games of all time: the myriad branching pathways of School Days; the emotional punch in the face that is the coming of age story Kira Kira; the genuinely amusing ridiculousness of My Girlfriend is the President; the wonderfully crafted fantasy world of Aselia the Eternal. I absolutely adored all of these experiences, but at the same time I was also conscious of the fact that there were only a few people I knew who would appreciate these games for what they actually were rather than what they thought they were.

I have a few friends who err towards the "otaku" side of things -- both male and female, it's perhaps worth adding -- who recommended a few other experiences that they thought I might want to try, having seen the sort of experiences I was enjoying. One of these was Gust's Ar Tonelico series, which I looked back on in great detail here so won't repeat myself on that note, and another of which was Idea Factory and Compile Heart's Hyperdimension Neptunia series. Both of these were published by NIS America in the West; both are regarded less than favorably by the mainstream; both are, conversely, beloved by their respective groups of fans.

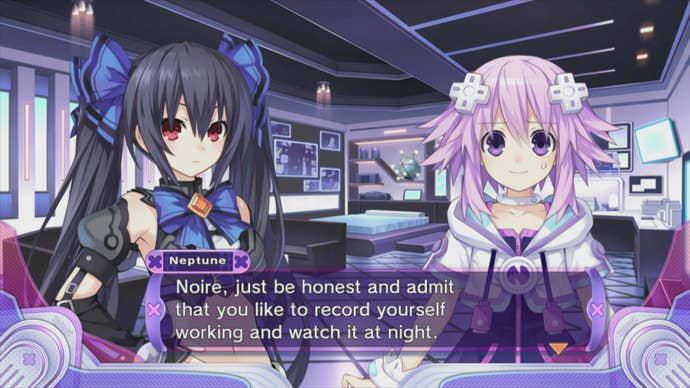

Hyperdimension Neptunia in particular is a series that endures a lot of criticism from outside the niche it occupies. Each of the three games has improved significantly on its predecessor, though each is still technically inferior to the vast majority of other games on PS3, suffering low framerates, chunky visuals and somewhat repetitive gameplay -- enough to put some people off. Others, meanwhile, find the games' "jiggly boob" event pictures and distinctly Japanese sense of self-referential, cheeky, occasionally perverted sense of humor distasteful or gratuitous, and are discouraged from playing the game for these reasons instead.

Personally speaking, though, ever since I fell in love with that curious cast of personified game consoles and developers in the first game, all the flaws ceased to matter to me, and I'm clearly not alone in that -- we wouldn't have had three games brought to the West otherwise. I have found all of the Neptunia games enormously enjoyable primarily for the entertaining interactions between the characters, not necessarily their gameplay -- though it's worth noting that Neptunia mk2 and Neptunia Victory are both also considerably better games on the whole than their extremely clunky but oddly endearing predecessor.

"Cultural norms between Japan and the West vary greatly at times in terms of sexuality, so what could seem fairly tame in one region, may be construed as completely inappropriate in others."

Ryan Phillips, NIS America

I was also pleasantly surprised to discover as I progressed that the Neptunia series is, despite its obvious fanservice, actually a lot more positive towards women than you might think on first impression. The entire cast is made up of very capable women who never need a man to fix their problems -- men are, in fact, usually relegated to subservient and/or incompetent roles when they do appear in the series, which isn't that often -- and in all three games it's quite strongly implied that all the main cast is if not outright gay then certainly bisexual. This latter point doesn't tend to be played for titillation, either; it's simply something taken for granted, much as it is in yuri [lesbian-themed] anime and manga. The idea of non-heterosexual lifestyles being depicted as so normal they're barely worth mentioning or drawing attention to is actually quite a powerful, positive message to send, and I find myself wondering how many people even knew that about this series.

In other words, there's a lot going on beneath the surface of a game like Hyperdimension Neptunia and it's certainly not an isolated case, either: we saw something similar with Time and Eternity a while back, too. This was another NIS America-published title widely derided for superficially appearing to be riddled with sexist fanservice and featuring an obnoxious main character, when in fact the truth of the matter was that it was merely a title firmly in keeping with the sort of characters and situations found in your average anime -- and one which, upon further investigation, revealed itself to have plenty of enjoyable hidden depths and interesting characters.

In all these cases, there's a certain amount of cultural context to consider that the most vocal critics don't seem to be bearing in mind; this is, to a degree, a valid viewpoint given that we tend to judge media we consume via our own cultural standards rather than those of the country of origin, but at the same time this also raises questions about whether or not it's fair to do so. These games, after all, weren't originally developed for "us," though there is, of course, a clear, passionate market in the West for these types of experiences.

So let's hear from the people behind the Western releases of these provocative titles.

About a month ago, Xseed Games announced that it would be bringing the 3DS title Senran Kagura Burst to the West. For those unfamiliar, Senran Kagura Burst is a game whose notoriety -- justified or not -- primarily comes from its all-female cast of ninjas who engage in fights and who, in the process, tend to find their clothing getting destroyed. As you've probably figured out by now if you've read what I've written above, things aren't quite that simple, as Brittany Avery, production assistant for the company, explains to me.

"Sexualization involving women and how women should be presented in games is a hot topic that has given birth to a lot of intense and interesting debates."

Brittany Avery, Xseed Games

"Despite the first impression it gives, SKB is a complete story with fully developed characters," she says. "Their outer appearance is just, ah, a little bustier than usual."

Senran Kagura Burst is actually a combination of side-scrolling beat 'em up combat and visual novel storytelling sequences, and it's through the latter in particular that the game shows that it's more than just juvenile titillation.

"It's about accepting those who appear to be different from you based on the surface," says Avery. She acknowledges that the Senran Kagura series as a whole is primarily targeted at a heterosexual male audience, but believes strongly that Burst in particular, being the lightest on fanservice content, can appeal to both men and women due to the fact there's a lot more going on than a quick glance might suggest.

"Some of the girls are relatable with their problems," she explains. "I identified with certain personality quirks Katsuragi had, but other girls might identify with Mirai's self-esteem issues, Asuka's interest in self-improvement as an independent person over romance, or Yagy?'s unrequited feelings. Each girl is quite different."

Avery believes the controversy Senran Kagura has attracted has been blown out of proportion to a certain degree -- as has the related controversy surrounding Xseed's decision to bring it, uncut, to Western gamers.

"Sexualization involving women and how women should be presented in games is a hot topic," she notes. "[It] has given birth to a lot of intense and interesting debates, so any game that indulges in any form of sexualization, regardless of intensity, context, or whether people have played the game or not, becomes part of that."

Out of curiosity, I asked Avery at this point if she had any opinions on Dragon's Crown, which attracted similar controversy to Senran Kagura for its depiction of women -- arguably even more so, due to Atlus' relatively high profile compared to Xseed. In this world of tightly PR-controlled statements from developers and publishers, I was pleasantly surprised to actually get a response -- though she took great pains to note that her opinions were her own and not representative of Xseed as a whole.

"I do think a lot of the people who disagree with how [Senran Kagura's] girls are presented aren't aware of the game in its entirety."

Brittany Avery, Xseed Games

"I thought, like how I feel about Senran Kagura, the whole thing was really blown out of proportion," she says. "Much worse games haven't caused that much of a fuss! I pre-ordered and played Dragon's Crown myself, choosing the Sorceress as my playable, and it's interesting since it's this Dungeons & Dragons-style game where my appearance -- so far, anyway -- has had positively no effect on the story at hand. You're always referred to by the narrator as 'you' regardless of whether you chose to be the Fighter, Hunter or Amazon. It's sexual and many will agree disproportionately silly-looking, but I don't think it's in any way demeaning since you're not perceived as a lesser character by in-game design depending on who you choose. I think the only complaint I have is not having a shirtless Fighter, perhaps -- c'mon, DLC!"

Returning to the topic at hand before she got too distracted, I asked Avery what she would say to those who would point the finger at Senran Kagura's content and visual style and bust out that overused adjective "problematic."

"I don't necessarily think anyone's opinion is wrong," she says. "It's a matter of whether they like or dislike the features. But I do think a lot of the people who disagree with how the girls are presented aren't aware of the game in its entirety, so I feel it's a personal mission to educate [them] about every part of the game. If you feel it's important to discuss the 10 per cent of the time there's girl talk involving boobs, I feel it's important to also discuss alongside it the 70 per cent of the time when they're struggling with the concept of what it means to be a shinobi and how they should really be perceiving their enemies, or the 20 per cent of the time when they're just being normal girls doing normal things.

"These are characters with the same amount of heart as the characters in JRPGs Xseed Games is normally known for putting out," she adds, emphatically. "Another misconception worth noting is that the game is thought by some to be about in-game male characters all being perverts participating in fights where girls have their clothes ripped, or that they're overpowering these girls. This is all completely, completely incorect. There's only one major male character in Burst; he's a 40 year old teacher from Hanzo Academy who would never even dream of looking at the girls he teaches as anything less than his students; he sees them as a parent sees his children. If you've played Corpse Party, think of how Ms. Yui thinks of her students."

I was glad Avery brought up Corpse Party; not only is it one of my favorite games of the last few years, it's also one that successfully pushes the boundaries of what is regarded as "acceptable" or "mature" content on consoles and handhelds -- markets that are typically rather more prudish than the completely open PC marketplace. I asked her whether Xseed had ever had any difficulties bringing "mature" titles like this to the West.

"Not at all," she says. "Any game can have what is considered mature content -- but that doesn't automatically mean it's being revolutionary in pushing barriers or that people have to accept it. It might just be a badly written or designed game that's using shock value for numbers.

"I think the most important thing about mature content is how it's used, or its presentation," she continues. "In the case of the first Corpse Party, its extreme violence with no way for any of the characters to defend themselves was meant to show just how powerless they were as people; it was meant to show raw fear and distress, not some sort of magical 'overcoming hope' scenario. Whenever things looked hopeful, it ripped it out of the hands of the characters in an instant and left the player fearing for the slow, audibly excruciating torture that awaited them. It presented itself beautifully and because we loved it as a game overall, we knew that others would as well." I certainly did; that feeling of total helplessness the game engenders on numerous occasions is something not many other games dare to touch on, and it makes Corpse Party's uncompromising nature all the more memorable. I'm grateful to have been able to experience it.

It's abundantly clear that both Avery and Xseed as a whole strongly believe in -- and genuinely love -- their products, and by doing this they're able to cater to a sharply focused demographic who believes in and loves the same things. It may be smaller than the broad audiences big-name publishers typically court with a new release, but these niche groups tend to be significantly more passionate and vocal -- and word of mouth plays a key part both in making these games successful and in addressing misconceptions from the broader public.

"A game can have extreme violence and suggestive or sexual situations that you object to," continues Avery, "but it might also be a damn good game. If you refuse to play it outright, you might be missing out on something that weaves that content into its structure well or overall has a lot more beneath the surface than that mature content. Only way to find out is to play it. I'm not sure how the media could help, but I do think publishers are doing a great job in recent years in becoming more opinionated about their products. Thanks to social media and forums, it's a lot easier to turn off the PR speak sometimes and just say how you really feel about something; that's been very important in helping people become more accepting of content that might not have stood a chance otherwise. Discussion and communication is key."

Avery knows what she's talking about here; when she's not working hard on Xseed's latest titles -- her current project is an upcoming new Rune Factory game -- you'll often find her on Twitter passionately explaining why you should care about the company's new releases and announcements, or why people shouldn't make kneejerk judgements on titles like Senran Kagura based on often inaccurate preconceptions. It's something we can all help with, too; while it's important to bring up and discuss content that might make people feel uncomfortable or excluded, it's also important to give a fair and balanced picture of what these games are actually all about -- because more often than not, T&A isn't intended to be the focal point of these experiences.

Ryan Phillips, NIS America's PR and marketing manager, concurred when I asked him about public perception of NISA-published series such as the aforementioned Hyperdimension Neptunia and Ar Tonelico, as well as other controversial releases from the company such as Mugen Souls.

"One major theme that is often overlooked in all three of these series that you mentioned is that they all contain a strong female cast," he notes, echoing my own thoughts, unprompted. "In the end, [this] offers a slightly different experience compared to the standard hero/female counterpart RPG formula. On top of that, the characters aren’t two-dimensional at all. The Neptunia series has become a very popular franchise for us because the characters have completely different personalities and the way they interact with each other provides for a really great story and situations."

Phillips is under no illusions; he freely admits that these games have a clearly defined target demographic, but this isn't necessarily a bad thing. On the contrary, it means that NISA's titles -- and those from other, similar publishers like Xseed -- feel much more personally tailored to those who enjoy them, rather than providing an experience that is watered down in an attempt to appeal to a broader, perhaps more profitable audience. Phillips notes that there is also, as previously noted, a cultural component to consider.

"We cannot deny demographics with certain series, as they were made for a particular audience before they even made it overseas to North America and Europe," he admits. "In Japan, on the whole, these types of games are sold to heterosexual men.

"We know that these types of RPGs aren’t for everyone," Phillips continues. "However, one really important thing that we have to remind those who view the strange mechanics in our games as 'problematic' is that cultural norms between Japan and the West vary greatly at times in terms of sexuality, so what could seem fairly tame in one region, may be construed as completely inappropriate in others. There is a niche RPG market out there that is pretty in tune with Japan and its culture, so we ultimately market these titles towards them. As game consumers, it’s our ultimate decision whether to purchase the game or not, but on the whole, if people can see past some elements, our games do have some really great stories, memorable characters, and lastly offer a lot of content for the price."

A recurring theme in both Avery and Phillips' answers is that of "seeing past" the content that some find objectionable, and it's an important point to consider. As Jeremy wrote a while back, there are a number of great works in all forms of media that contain their own troubling content -- content that people can usually overlook in favor of seeing the big picture, or come to understand in context of the complete work. There's no real reason why we can't do the same for games -- by all means acknowledge there's content in these titles that some find distasteful for various reasons, but at the same time, don't let it define the experience as a whole, because that's usually not the intention. As Avery says, if you feel it important to discuss the 10 per cent of the time that there's boob talk, also acknowledge the other 90 per cent of the game.

"One really important thing that a lot of people may not know about us is that we first have to make sure that the entire company is comfortable with working with a particular title before we decide to license it."

Ryan Phillips, NIS America

"I think that when it comes to viewing certain Japanese developed RPG games, you have to have an open mind and understand that they were made intentionally for a certain fanbase and adult sub-culture over there first and foremost," continues Phillips. "We do our best to interpret and localize the language to help others understand what the characters are saying, but the culture permeates farther than just text and voices, and that is where Westerners have to try to understand and realize that they are actually experiencing culture visually as well. I had mentioned it before, but trying to understand the cultural difference between norms is a huge part in being able to beginning to understand some of the niche Japanese games out there."

Could we do better? Of course, but there's nothing inherently wrong in catering to a specific market if it's a proven one. The thing that the industry as a whole would do well to explore is catering to a larger number of these specific markets rather than just the heterosexual male demographic. This is something we're finally starting to see with the more widespread Western release of otome games -- games specifically aimed at women -- such as the recent Sweet Fuse on PSP and Vita, though there's still a way to go.

"Perhaps if they introduced a male playable character with fanservice on the same level as the girls in a later game, that would draw in more females?" muses Avery, contemplating the potential future of the Senran Kagura series. "It might also draw in more problems in North America as well, having a male with the capabilities of causing battle damage towards females, but I'd be all for it if it was equal opportunity.

"I can't speak for the company as a whole when it comes to the games we target," she adds, referring to Xseed's overall strategy, "but I know that we usually choose games people within the company are interested in that won't kill us financially. If not a single person likes a game we're looking at and we aren't enthusiastic about the idea of working on it, we pass on it. I'm definitely the biggest fan of Senran Kagura in the office, and I've pestered my boss on a number of occasions for super-niche titles that most wouldn't even dare look at, but he's gone out of his way to try and pursue a few after crunching some numbers and seeing if it could open up a new audience for us. I'm personally very interested in otome games but it doesn't really matter what the genre is; if it's a good game and we can justify the costs, we're going to try it out."

Phillips is a little more conservative on the subject.

"We've found over in the West that women do play our games, and do enjoy the all-female cast of characters," he notes. "Game-wise, we haven't delved too far into the otome/yuri/yaoi [aka "boys' love"] markets; however, this fall on our anime side we will be releasing Yuru Yuri and also Brave 10, both of which touch on the yuri/yaoi genres.

"One really important thing that a lot of people may not know about us is that we first have to make sure that the entire company is comfortable with working with a particular title before we decide to license it," he continues, echoing Avery's description of how Xseed chooses what titles to bring to the West. "There have been a few that have been proposed, but in the end if we weren't comfortable working on them internally, we didn't end up working on it. If it passes the test with us internally, there hasn't been a problem with it being accepted by distribution partners or the platform companies."

We're already at a stage where it is literally impossible for one person to play and appreciate every single new release out there, so it makes a lot of sense for publishers like NISA and Xseed to cater to specific niches rather than trying to appeal to everyone. The important thing to remember if you're outside those niches, however, is that all isn't necessarily as it initially appears with these games -- the boobs and butts might be front and center if you give them nothing more than a quick glance, but take the time to delve a little deeper and you'll find there's often far more interesting things going on in these titles than in parts of the industry that choose to play things a little safer.

And that's something I'm all for. How about you?