The Harsh History Of Gaming Microtransactions: From Horse Armor to Loot Boxes

Loot Boxes are currently the most debated topic in gaming, but we've had over a decade of in-game money grabbing.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

Loot boxes are a trend that the game industry has heartily bought into in 2017. They've been around for almost a decade in the massively-multiplayer online space, but since the release and success of Overwatch in 2016, the business model has had more visibility. Major developers and publishers have adopted the model before and since. What thrust the mechanic into the spotlight was a trio of major releases: Forza Motorsport 7, Middle-Earth: Shadow of War, and Star Wars: Battlefront 2.

Together, the three have fueled a backlash against loot boxes. Some have sworn never to buy a game with the business model attached. A number of players fear the slippery slope: if you ignore loot boxes now, then publishers and developers will double down on the form. And that's a fear you can understand, if you take a look back at business practices in the industry. So let's wander back through the history of all the ways that publishers have aimed to drain your wallet.

Downloadable Microtransactions: Every Nickle and Dime Matters

Microtransactions first gained large-scale visibility way back in 2006. Bethesda Softworks had just released The Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion for PC and Xbox 360 in March of that year. It was still early in the Xbox 360's lifespan and Oblivion stood as a critically-acclaimed and fan-favorite RPG exclusive for the console.

Microsoft had previously offered up the idea of microtransactions in early 2005, as a feature of the new Xbox Live Marketplace prior to the launch of the Xbox 360. The platform holder played microtransactions up as a new revenue stream for publishers and developers. At the same time, Microsoft called it a boon for players, who didn't have to spend $5, $10, or $20 for bundles of content they didn't want. Instead, they could directly buy what they wanted for $1 to $5.

"Generally if you do anything less than $5, you end up eating up the bulk of that $5 in transaction fees," said Xbox Live general manager Cam Ferroni told Reuters at the time. "At the heart of it'll be a points-like system where you buy points and then use those points to make purchases."

"Not only do you have to sweep away the distinction between virtual and real, you have to stop looking at video games as a toy and start looking at them as an entertainment service," Synthetic Worlds author and Indiana University professor Edward Castronova said in the article. This is one of the earlier mentions of the concept of games-as-a-service.

Microsoft itself offered a winter-themed outfit for Kameo: Elements of Power for $2.50, alongside new maps for Perfect Dark Zero and new cars for Project Gotham Racing 3. None of these early microtransactions took off in a major way, but it was all about Microsoft showing a proof of concept to other publishers.

Bethesda was the first third party publisher to jump-in on Microsoft's idea. In April 2006, it released the first of its planned expansion content for Oblivion. That release was the infamous Horse Armor Pack. For 200 Microsoft Points ($2.50) on Xbox 360 or $1.99 on PC, players could purchase alternate armor sets for their in-game steed. Fans were previously fine with the idea of microtransactions, but were absolutely shocked by the pricing of the horse armor. In response, Bethesda simply moved forward with its plans, releasing new themed homes, a new dungeon, and new spells.

"We're not going to make any knee-jerk decisions based on it [the armor] being available for five hours. We'll see what folks think and put out a few others we have planned and figure out where to go from there," said Bethesda VP of PR marketing Pete Hines at the time. "Some folks seem excited and are already using it, others don't want it. Maybe those folks will really want the Orrery, or the Wizard's Tower. We'll see when they come out and use that info to determine what we put out, how much, etc."

It was heresy in the gaming community. Fans railed and raged at Bethesda. Since then, horse armor has been held up as an early infamous example of downloadable content and microtransactions gone wrong, but the actual material hit to Bethesda was almost nil. Fans bought the horse armor, making it one of the Top 10 purchased downloads for the game on Xbox Live. Fans purchased the Wizard's Tower and Thieves Den, which were just different homes for the player. Bethesda made a heap of money on top of the $60 fans paid for the Xbox 360 version of Oblivion.

In response to loot boxes these days, people are actually stating a preference for direct microtransactions like the horse armor. Instead of getting a blind box of random content, people would rather have the ability to directly purchase what they want in a game. Some games, like Dead or Alive 5: Last Round, subsist on an endless stream of new costumes and characters that players can purchase directly. Nintendo has made it an art form with Amiibo, a line of $13 figures with near-field communication (NFC) chips, allowing them to unlock additional content within a wide variety of games.

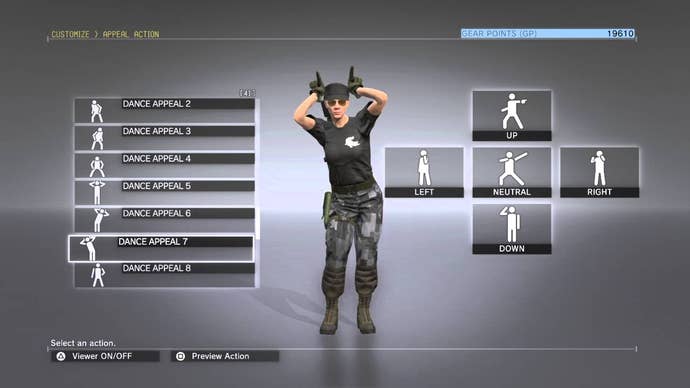

No one even blinks at the addition of direct microtransactions anymore. People will happily pay $4.99 for a character, $2.99 for a character costume, or $1.99 for a series of emotes. Given that, horse armor seems rather normal and inexpensive in comparison.

Online Passes: Paying The Gatekeeper

The gaming industry has always had a problem with the second-hand market. Stores like GameStop, pawn shops, and services like Ebay allow consumers to sell their used games for money. In the minds of publishers, the problem is that the revenue from those sales don't benefit them. They see every subsequent used sale as a missed opportunity for the sale of a new copy.

In 2010, Electronic Arts had an idea about how to fix the problem, or at least lessen the perceived blow. A year prior, the company had been offering bonus content for titles like Mass Effect 2, Dragon Age: Origins, and Battlefield: Bad Company 2 under the Project Ten Dollar initiative. Buy a game new and you'd get a code that would unlock new outfits, characters, or items. Buy a game used and there'd be no code. But EA wanted to go a step further. The expansion of Project Ten Dollar became the Online Pass.

New games would come with a single-use code inside the package, just like Project Ten Dollar. The difference was inputting the code wouldn't unlock extra content, it would unlock previously-standard features. Tiger Woods PGA Tour 11 was the first game with the system, requiring the online pass code to unlock online team play and other online modes. The pass was offered that year for NCAA Football 11, NHL 11, Madden NFL 11, NBA 11, FIFA 11, and EA Sports MMA. Buying any of those games second-hand meant having to pay $10 for a new pass to unlock the online play.

"We've made a significant investment to offer the most immersive online experience available. We want to reserve EA Sports online services for people who pay EA to access them," said current EA CEO Andrew Wilson, who was EA Sports senior vice president at the time. "In order to continue to enhance the online experiences that are attracting nearly five million connected game sessions a day, again, we think it's fair to get paid for the services we provide and to reserve these online services for people who pay EA to access them."

The online pass built upon an idea Sony Computer Entertainment had earlier tried: SOCOM U.S. Navy SEALs: Fireteam Bravo 3 for PlayStation Portable came with an unlock code for online multiplayer. It was there to protect against piracy, which was a major problem for the PSP.

Once EA launched games with online passes, Ubisoft followed suit a year later by opening up the Uplay Passport system. Games like Driver: San Francisco worked like EA's titles, locking players out of online play if they lacked the single-use code packed in with new releases. Activision, Warner Bros, THQ, and more followed EA and Ubisoft down the path of online passes.

There was heavy criticism from players over online passes. Some wanted to be able to freely sell and repurchase games in the second-hand market. Players who generally rented games were completely out of luck with the new business model. Some players warned that content that was normally in the game would be locked behind a code in the future.

After three years of using the system, Electronic Arts was also the first to step up and kill it. Reportedly in response to planned DRM measures in the upcoming Xbox One and PlayStation 4, EA canceled the Online Pass program in May 2013. Publically, EA said it was just listening to feedback.

"Initially launched as an effort to package a full menu of online content and services, many players didn’t respond to the format. We’ve listened to the feedback and decided to do away with it moving forward," EA senior director of corporate communications John Reseburg told GamesBeat in 2013.

Online passes ended as one of the few times that the industry completely backed away from a business model with additional transactions. I'd say that's probably a victory?

Season Passes: Publishers Are Doing You a Favor, Right?

A year after Electronic Arts launched the online pass, Rockstar Games offered their own pass. The Rockstar Pass for L.A. Noire gave players access to all of the planned downloadable content–two additional cases, new outfits, new weapons, and an item collection challenge–at a solid discount. While buying all of that DLC would cost players $20 individually, the Rockstar Pass was only $12 on PlayStation 3 or 960 Microsoft Points on Xbox 360. If you were planning to buy all the content, you saved $8.

The trick is, most players weren't likely to buy all the DLC. By bundling everything up and offering a discount, Rockstar Games was able to entice players to buy content they normally wouldn't.

The 2011 reboot of Mortal Kombat, which actually launched a month before L.A. Noire, offered its Season Pass in June of that year. That season pass would establish the fighting game standard, giving players access to all additional character releases. Activision's Call of Duty franchise launched the Call of Duty Elite membership for Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 3 in September 2011, acting somewhat like a Season Pass. Elite was a $50 a year subscription fee that unlocked access to all CoD map packs for that year, in addition to streaming content, a special site, and more. The Season Pass practice eventually moved to most major titles in 2011 and beyond, including Borderlands 2, Destiny, Evolve, Gears of War 3, Forza Motorsport 4, and Battlefield 3.

Those who take issue with the system point out that publishers are essentially getting players to pre-order additional content: You put down $60 for the game and at the same time $20-30 for the downloadable content. Many times, players have no clue what they're paying for: characters are hidden, future expansions aren't detailed. You're pre-purchasing in the hopes that a publisher or developer will deliver on some nebulous promise. This also led to the rise of Deluxe Editions, which are generally just the base game with the season pass already included.

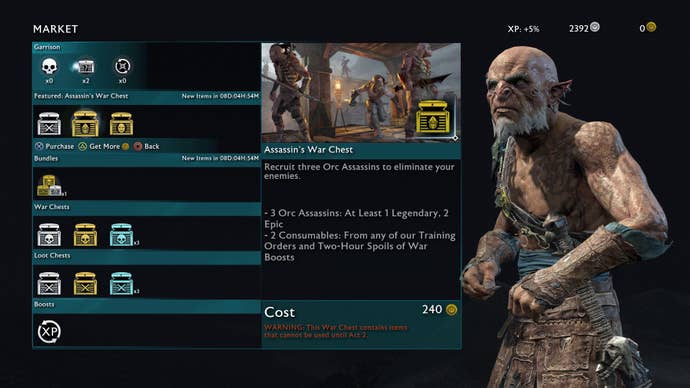

Season Passes are still going strong to this day. Some of the loot boxe games mentioned at the beginning of this article also have season passes. Forza Motorsport 7 has the Car Pass, giving you access to six monthly car releases (42 cars in total) for $29.99. Middle-Earth: Shadow of War has an Expansion Pass, offering access to four expansions for $39.99. The upcoming Assassin's Creed Origins has a Season Pass with more story content and two outfit packs.

On the side of consumers, there's no real visibility as to whether the prices originally set for DLC have any meaning. There's value added to digital content: some of that is related to the production of said content, but players never know how much. If the cost to produce a DLC pack is $2 per consumer, it's suggested store price is $6, and the Season Pass brings that down to $4, the publisher has still made a hearty profit.

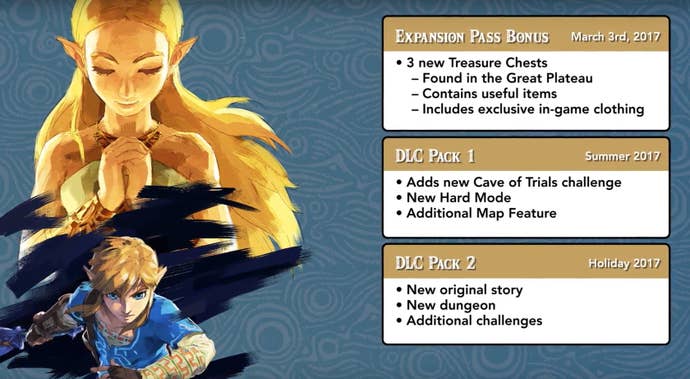

Season Passes don't surprise players anymore. Hell, even The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild offered a season pass this year, to very little in the way of condemnation for a publisher that previously avoided such measures. The perception is simply that the discounts are worthwhile, especially for the avid and fervent fans of a game.

Loot Boxes: Step Up And Try Your Luck

All of this brings us to loot boxes. Loot boxes are the current zeitgeist for our industry. The idea is either through progression, in-game currency, or real money, the player is gifted a mystery box. Inside of the box can be costumes, skills, gear, or random items specific to the game. The player wants the unlockable items and these blind boxes are the only way to get them. In some cases, there are alternate methods of purchase available, but the random luck of the loot box is designed to be the easiest way.

They've been used in digital collectible card games (CCG)for some time now as a digital form of the trading card booster pack. Much like players of Magic the Gathering buy blind booster packs to get the cards they want, titles like Hearthstone and Gwent have players tearing open digital packs. In many cases, these digital booster packs are the only way to get the cards, making them the only real method of progression in CCGs. Even Magic has gotten in on the action, with Wizards of the Coast offering a web-based and PC client of the card game. Despite this, the genesis of loot boxes stretches farther back.

Publishers and developers sometimes entice players by making more expensive versions of loot boxes, which have a better chance to drop better stuff. Rarity is one of the common ways companies get players to pick up further loot boxes; open more boxes, get a chance at a better, more rare item. Some games, like Overwatch, offer seasonal, limited time events, encouraging players to buy more boxes to get the seasonal skins they want.

The loot box model started in Chinese and Korean massively-multiplayer and free-to-play games, but the first shot at them on the Western side of things was Valve's Team Fortress 2. In June 2011, Valve transitioned the game to a free-to-play business model after the launch of the Mann-conomy update in 2010, which introduced crates and item trading. MMOs that fell on hard times, like Star Trek Online and Lords of the Rings Online, switched to the model when they went free-to-play as well.

There were paid games that offered loot boxes at the same time, though usually they left the mechanic for online multiplayer modes. Mass Effect 3's Galaxy at War multiplayer launched with purchasable equipment packs. Counter-Strike: Global Offensive added weapon cases in 2013, requiring an additional key to unlock. (PlayerUnknown's Battlegrounds toyed with a similar system.) Battlefield 4 launched with Battlepacks, adding real-money purchases in 2014. Releases from 2016 were riddled with loot boxes: Call of Duty: Infinite Warfare has supply drops and zombie crates, Halo 5: Guardians has REQ Packs, Battlefield 1 has Battlepacks, and Gears of War 4 has Gear Packs.

Loot boxes began in countries like China and Korea, and those countries have since cracked down on the business model as a form of unregulated gambling. China's Ministry of Culture laid down laws in 2016 that forced all companies to disclose the odds of specific items dropping from loot boxes in their games. This disclosure included information like escalating odds, meaning opening more boxes at same time increased the chance of getting rarer items, and the true drop rate of some items, falling as low as 0.1 percent in some cases. South Korea has tried to draft similar legislation.

As part of the gambling conversation, folks and organizations have begun to understand that since real-money can enter the picture, these virtual items carry real value. Valve is under several lawsuits involving underage and illegal online gambling related to Counter-Strike: Global Offensive. Apparently, there is a long-standing problem of people using rare CS:GO skins to bet on professional matches. Which makes sense, given that some skins are worth hundreds of dollars.

Unfortunately, it's a grey area at the moment, especially in the United States. Even among gaming communities, people have various tolerances for business model. Fans of Overwatch are generally fine with loot boxes, because they feel that only cosmetic items like skins, emotes, and sprays come from them. In contrast, Shadow of War is getting pushback because the orcs you can gain from War Chests impart direct gameplay benefits.

How Far Will Consumers Let It Go?

Even without the gambling conversation regarding loot boxes, there are still whales and even casual players who keep buying into additional games content. Overwatch costs $40 for the standard edition, but I've probably put $10 into the game during each seasonal event to get some of the special skins. Given that there have been 8 events since launch that's around $80 for the game, meaning it'd have been $120 if I purchased it at launch.

With another Blizzard title, World of Warcraft, I've purchased the base game ($60), and every expansion up until Warlords of Draenor, when I began reviewing the series professionally (4 x $50). Add in the monthly fee that I'm mostly paid since launch in 2004 (154 x $15), and the various pets and mounts I've purchased on the Blizzard Shop ($40 in total?), and it begins to add up as a very profitable game for Blizzard. $2,610 from me alone. It's easy to see why companies want to move in this direction, and I can't say I'd do anything different, as WoW has provided me with hours upon hours of enjoyment. Players balk at prices for additional game content, unless it's their favorite platform holder, publisher, developer, or game series. Then's it's a-okay.

The backlash against loot boxes is rising in 2017, but business model and others like it have been around for some time in the industry's biggest games. What's changed in this case is Shadow of War bringing the loot boxes into the single-player side of the equation, while most games have kept the business model purely on the multiplayer side of the things. Likewise, having three major titles with loot boxes occupying public consciousness at the same has highlighted the growing trend.

It's not new, just salient. And if this look back at history is any indication, being afraid of the slippery slope isn't all that shocking. So what is the gaming community going to do about it?