The Game Boy Legacy: A 25th Anniversary Celebration

A quarter-century after its debut, we look back at the life and times of Nintendo's legendary portable console.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

They say only Nixon could have gone to China. Similarly, only Nintendo could have created Game Boy.

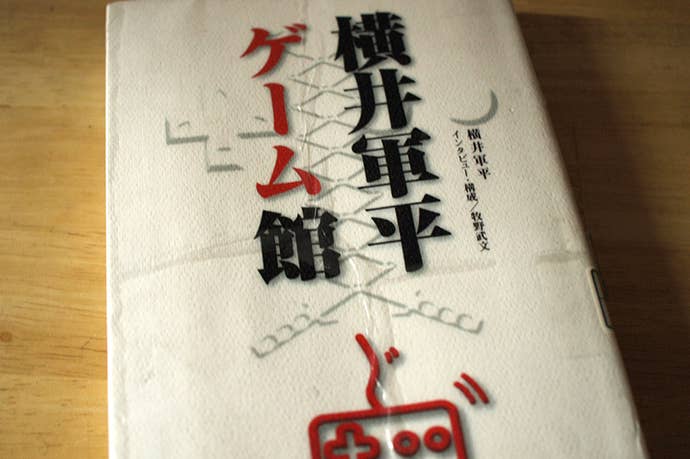

Only Nintendo would have bothered releasing a handheld console so deliberately underpowered, so hindered by seemingly terrible design choices. Only Nintendo would recognize that portable hardware design is about tradeoffs and compromises, and would have chosen to compromise the features that other console makers view as essential selling points in favor of a broader, more pragmatic appeal. In the 25 years since Game Boy's Japanese debut, only one other portable competitor (Bandai's WonderSwan) has attempted to compete with Nintendo on Game Boy's terms rather than according to the conventional wisdom of game hardware design. And only one other handheld game system has ever outsold Game Boy's 118 million units: Its own successor, the Nintendo DS, which repeated history and once again proved the wisdom of Game Boy's father, the late Gumpei Yokoi.

Origin Story

The Game Boy's origin story begins, famously, in the late 1970s as Yokoi watched a businessman on the train fussing with a digital LCD wristwatch. What if the simple mechanisms of that watch – the tiny buttons, the preprinted LCD screen – could be converted into a legitimate game system, he wondered?

At the time, the only available portable game systems came in two forms: Mattel's LED devices (and their imitators), which involved moving lights around a preset grid of red diodes, and Milton Bradley's Microvision, which featured interchangeable cartridges and a black-and-white LCD. The Microvision wasn't capable of games more complex than Mattel's devices, though; its 16x16 screen resolution offered only the most rudimentary play experiences.

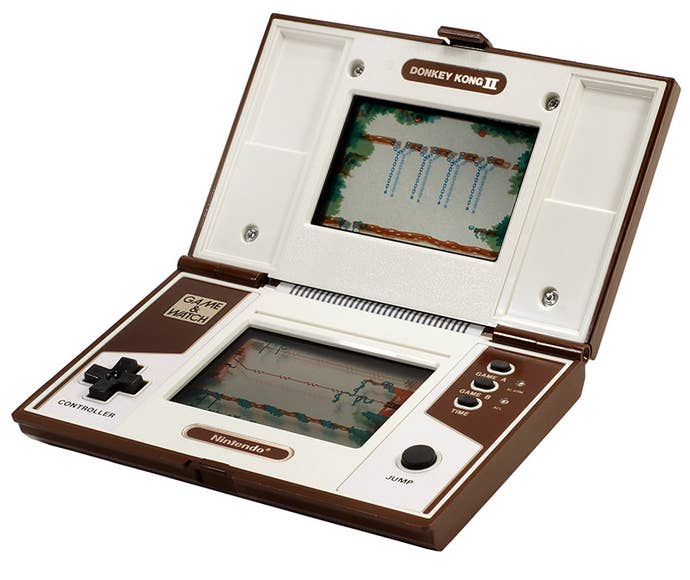

Yokoi's creation, on the other hand, was capable of more nuanced and varied game types. By pre-printing screens with detailed illustrations designed to mimic subtle animation, the Game & Watch series felt more in line with high-end arcade games. Of course, it all boiled down to trickery, but the best Game & Watch titles turned players into willing participants in the charade. Best of all, by using standard wristwatch technology and manufacturing techniques, Yokoi kept prices on Game & Watch system's remarkably low – far cheaper than the comparatively clumsy Microvision.

Game & Watch proved to be a massive, if quiet, success throughout the first half of the '80s. While Donkey Kong's arcade popularity put Nintendo on the map, Game & Watch kept food on the table with a steady stream of simple, addictive, inexpensive games. Still, Microvision had one genuine advantage over Game & Watch: Interchangeable cartridges. Because Game & Watch's entire premise hinged on printing specific graphics on the system's screen, each unit fell into the old-school dedicated-device school of hardware design that Atari's 2600 had taken out behind the woodshed. Still, the units did well enough to remain in production throughout the '80s, even inspiring a number of imitators by competitors such as Tiger Electronics.

In fact, the Game & Watch's successor wouldn't arrive until nearly nine years to the date of the line's debut.

About a Boy

By 1989, the time for a proper portable game console had clearly come. Several companies had experimented with variants on the theme throughout the '80s, ranging from Coleco's famous tabletop adaptations of arcade games like Pac-Man and Nintendo's own Donkey Kong to the powerful Epyx Handy Game. Developed in 1986, the Handy Game was an extraordinary piece of hardware for its time: It offered a full-color backlit screen, a powerful processor, and – most importantly – ran on interchangeable carts.

Who knows how game history might have been different had Epyx been in possession of the capital to make the Handy Game a reality. But they lacked the resources, and eventually Atari took control of the system, rebranding it the Lynx and pushing it slowly toward a late 1989 release.

The Lynx's deliberate journey to market gave Nintendo plenty of time to set its sights on portable gaming. Flush with money from the runaway success of the Famicom/NES, the company tasked Yokoi with repeating his Game & Watch success, but this time in the form of a proper handheld console.

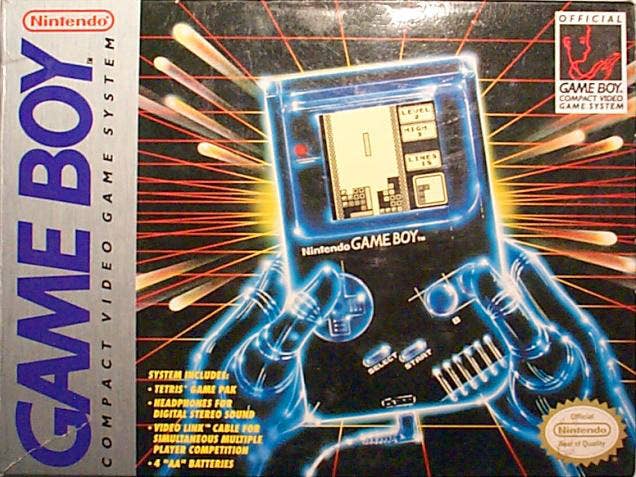

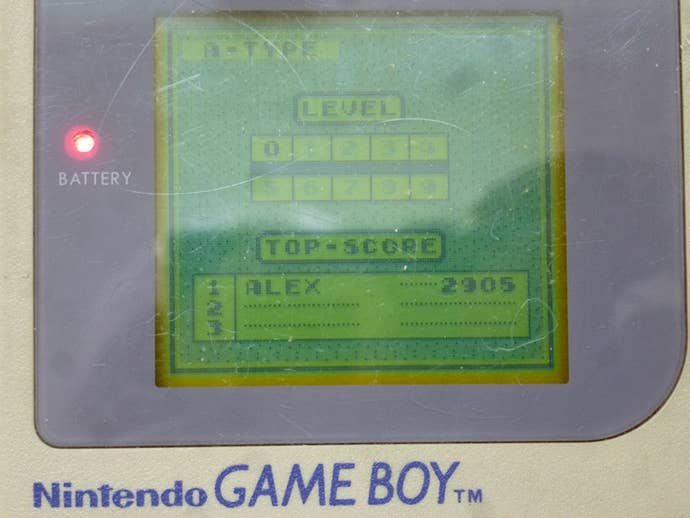

Yokoi rose to the occasion, creating a console that succeeded not in spite of but because of its limitations: Nintendo's Game Boy. Like the Game & Watch, Game Boy consisted of what were essentially off-the-shelf parts, a low-powered processor, and the cheapest screen technology Nintendo could possibly get away with. The result: An inexpensive console that ran for a dozen hours or more on four AA batteries.

"Nintendo's best success with the Game Boy is in its application of Gunpei Yokoi's design philosophy," says J.C. Fletcher, co-founder of handheld gaming blog Tiny Cartridge. "By keeping it relatively low-tech and low-priced, Nintendo was able to make the Game Boy something that kids could take anywhere and play for a long time without replacing batteries, and without parents having to worry too much about replacing it. It was a completely stress-free way to play games."

Despite its low cost, the Game Boy felt anything but cheap. Its rugged plastic case could withstand the unique abuses that children subject their expensive possessions to and keep ticking. Its simple, solid-state innards proved equally difficult to destroy. Ultimately, only the screen presented a genuine weak point, warping in heat or cracking from the force of an unfortunate drop onto a hard surface. Despite this remarkable durability, the Game Boy wasn't physically cumbersome in the least. Solid and compact, it was the perfect size to fit kids' hands, with a button-and-D-pad interface arranged to mimic the NES's.

"I always appreciated that Nintendo treated and designed the Game Boy as a toy, not bothering to implement the clock and alarm functions in the system's predecessor, the Game & Watch," says Eric Caoili, Fletcher's co-editor at Tiny Cartridge. "It has no other ambition other than allowing you to play something fun on the go. From its super durable casing to its colorful buttons, the Game Boy is designed to be thrown in your backpack, and taken out to play a quick game while you wait for your mom to pick you up after soccer practice."

The lateral thinking of withered technology

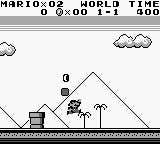

Game Boy's underlying tech reflects this purity of design and purpose. Offering just enough power to offer play experiences roughly equivalent to those on NES without necessarily incorporating all the bells and whistles – such as color graphics – the system managed to be just good enough to be fun, but stopped short of anything more elaborate or taxing.

"I think the Game Boy gave us something special in the 'pocket sized' game," says WayForward Technologies' Matt Bozon, who developed a number of titles for the 8-bit Game Boy family, including cult classic Shantae. "So many titles tried to match their living room console counterparts… It forced a transformation that squeezed out all but the core gameplay and most iconic visuals needed to convey the idea. That, combined with the need for shorter play sessions, created an entirely new game type. Recently handhelds have become powerful enough to make 'regular' games portable. But the Game Boy’s best titles suggest a genre of game that is truly a 'pocket sized game' in spirit, not merely a portable game."

Meanwhile, Nintendo's competitors approached the portable puzzle as if handheld systems should push the same envelopes as TV-based consoles. Despite featuring a lower screen resolution than the Game Boy, Atari's rechristened Lynx looked spectacular in action. Sega's Game Gear took the Game Boy's "NES-like experience" philosophy to the next level, boasting a slightly upgraded version of the chip set that powered its Master System console (which already trumped the NES's hardware).

But these advantages proved to be detrimental in practice. Both color consoles commanded prices considerably higher than Game Boy's budget-friendly $89 – and the costs didn't stop there. The beefy processors that made Game Gear and Lynx's remarkable visuals possible chewed through batteries in short order. Four AA batteries would power Game Boy for a dozen hours, while its competitors could barely coax a quarter of that from six batteries. Bad enough that the other systems cost twice as much at retail, but the fact that their power requirements cost six times the Game Boy's modest demands greatly hampered their portability.

"Everything the Game Boy and Game Boy Color did it did well," says Bozon. "The systems were kind on batteries, ran the games smoothly, and the visuals and audio were clear as a bell. Every drop of processing power went to gameplay. Other handhelds came and went, but you just couldn’t argue with the bread-and-butter simplicity of Game Boy.

"Other systems felt superior for one reason or another, but (aside from Neo Pocket Color) there was usually a catch – low battery life, most often, which was a system-killer. Nintendo also had the best games on handheld, and they never rested on their laurels. Even when the monochrome Game Boy had been dormant for about a year or so (I remember only Castlevania Legends and Mr. Chin’s Gourmet Paradise one year) they suddenly brought out Pokémon and the whole thing caught fire again!"

Punching above its weight class

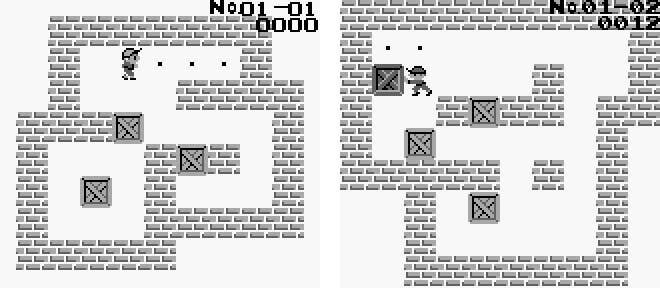

"Unlike this generation, handhelds like the Game Boy were extremely limited systems," says Origin Senior Writer Craig Harris, whose coverage of portable games at IGN made him one of the platform's most visible advocates during the latter Game Boy years. "They had to be to be cheap to buy and run off a set of AA batteries. I absolutely loved seeing what developers could pull off on these restrictive platforms. Great games have always been birthed out of system limitations, and it was thrilling watching developers come up with new techniques.

"Game Boy developers couldn't depend on hardware capabilities or even visuals to 'wow' their players. They had to work within the confines of the Game Boy and produce something that entirely revolved around the gameplay... low resolution, a handful of shades of gray, specific sprite size and number restrictions... developers still managed to squeeze great, noteworthy games out of these limitations."

Bozon agrees. "The limitations were severe, and that was its greatest advantage. The Game Boy could load two banks (about a single screen’s worth) of art, and that was it. If you wanted to load the entire alphabet, you’d have to write your dialogue carefully because every tile that went to a letter was one fewer tile you could have in your background. This led to much more forethought, showing more and saying less, and a lot less waste overall. Every pixel had to fight for its right be on screen, and as a result games were more likely to maximized their potential.

"Additionally, every trick we pulled looked amazing! Animating a tile to give the illusion of a parallax layer, or controlling literally four three-color sprites to give the illusion of a 12-color Shantae character really made the game look impressive. These tricks went a long way to make WayForward games stand out among the games that stuck to the rules of three- and four-color palettes."

Despite the system's modest capabilities, Nintendo built a number of interesting bonus features into the system. Former Nintendo composer Hirokazu "Hip" Tanaka once told me the Link Cable feature was the console's secret weapon. While as limited in its own way as every other facet of the machine, it opened the door to boundless creativity among developers. Nintendo's F-1 Race shipped with a special adapter that allowed up to four players to join up their systems and compete head-to-head, and the Game Boy Printer used the Link Cable to allow players to turn their game systems into tiny portable photo studios.

"What I liked about the Game Boy platform was that Nintendo wasn't afraid to experiment with it," says Harris. "The Game Boy Camera and Printer kicked off portable digital photography on the cheap. Kirby's Tilt 'n Tumble showed us what you could do in a system if you added motion sensors. Today, you're nothing if you're not incorporating cameras and gyroscopes in your portable devices... they're mandatory these days. Nintendo even experimented with mobile phone tethering for data transferring in Pokemon, and even the goofy eReader peripheral was a precursor to QR codes and how much data you can stuff into one."

By far, the most important Link Cable hack of all came from developer Game Freak, who devised a system that allowed players not only to fight one another in role-playing battles, but also to trade the virtual monsters they collected in the course of their adventures. Inspired by director Satoshi Taijiri's childhood love of capturing and battling insects, this conceit helped the Pokémon series explode in popularity around the world. In the process, the system found its second wind just as it was beginning to fade away.

While Game Boy soldiered on throughout the '90s, the platform slipped quietly into obscurity around the time the 32-bit generation hit the scene. By and large, it seemed to sell mainly because it didn't have any real competition in the handheld space once Lynx and Game Gear faded; between Game Gear's 1990 debut and the launch of the Neo Geo Pocket in 1998, the only significant portable platforms to appear on the scene were NEC and Sega's handheld versions of their respective 16-bit consoles, pricey and power-hungry. Meanwhile, Nintendo refined the Game Boy with 1995's Game Boy Pocket, greatly reducing the system's size, price, and power requirements while incorporating a much better screen.

While the platform soldiered away in the mid-'90s, its library remained largely unremarkable. Good games tended to go unnoticed by the graphics-obsessed gaming masses, or else ended up buried beneath the Game Boy's eternal landslide of generic puzzle clones produced on the cheap.

Flawed dogs

"I think the biggest frustrations [with the platform] came from seeing the low budgets given to Game Boy games," says Harris. "Third party developers got very little to make handheld versions of games, and that quality showed. Publishers added to the problem using the low capacity, non-EEPROM save cartridges, and that also affected quality (and gave us awful password saves)."

The system's low technology, frequently uninspired library, and fundamental alienation from the 3D, polygonal future of games unfolding on consoles and PCs made the system easy to ignore. Indeed, it helped entrench the notion that portable games could be easily dismissed, a perception high-end portable games continue to struggle again.

"The Game Boy firmly established, for better or worse, the idea of portable consoles for kids," says Fletcher. "It's only natural that something designed to be rugged and toy-like, and perfect for small people without TVs of their own, would attract development of kids' games, which is definitely a positive trait overall.

"But I believe the fact that it is perfect for kids accidentally created the stigma around handheld games. Adults play real games with all the graphics – so many graphics – and the little ones can play Heiankyo Alien on the school bus."

The system's toyetic nature wasn't all bad, though; in fact, it was part of the system's appeal. "It's such a charming toy to interact with," says Caoili. "There's that satisfying click you hear after pushing a plastic cartridge into its slot, and that lovely chime after flipping the on switch and seeing the Nintendo logo float down. Even the volume and contrast wheels were fun to roll up and down; it's a pleasure you don't get with the sliders and miniature buttons on modern devices."

Even if Game Boy's design and library did poison the well for future portable systems, you can't argue that Nintendo didn't know its target audience. The system's compact design, colorful buttons, and lo-fi tech made it a perfect fit for kids. That's something that never changed throughout the Game Boy's life, or even with its successor, Game Boy Advance. It wasn't until the Nintendo DS – which very deliberately dropped the word "boy" from its name – that Nintendo began to target an older audience with its handheld systems.

Yet even then, Nintendo never lost sight of the fundamental principles that Yokoi adhered to when designing the Game Boy: Low cost, durability, ease of use, even at the expense of raw power. Like Game Boy, the DS seemed laughably primitive when it launched – yet it managed to go on to become the second best-selling game system in the world with great software and an accessible design.

"It's not about the power, it's about what you do with what you've got," says Harris. "Sony's learned this first-hand with the PSP – they went top-shelf everything when they created the system, which kicked Nintendo's current-generation offering to the curb. Wasn't enough to take down the DS.

"I was baffled when Sony actually tried to do it again with the PS Vita. It's everything you want a gaming handheld system to be, top-of-the-line hardware, and beats the pants off the lower-spec 3DS. But it's the weaker hardware that's winning the gamers over, even when the prices of the two systems are comparable. Last I checked you can get a Vita for the same price or even less than a 3DS XL."