The Final Fantasist: A Conversation With Yoshitaka Amano

COVER STORY: The artist who has given life to so many Final Fantasy games speaks about his inspirations, the difference between fine and commercial art, and his current projects.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

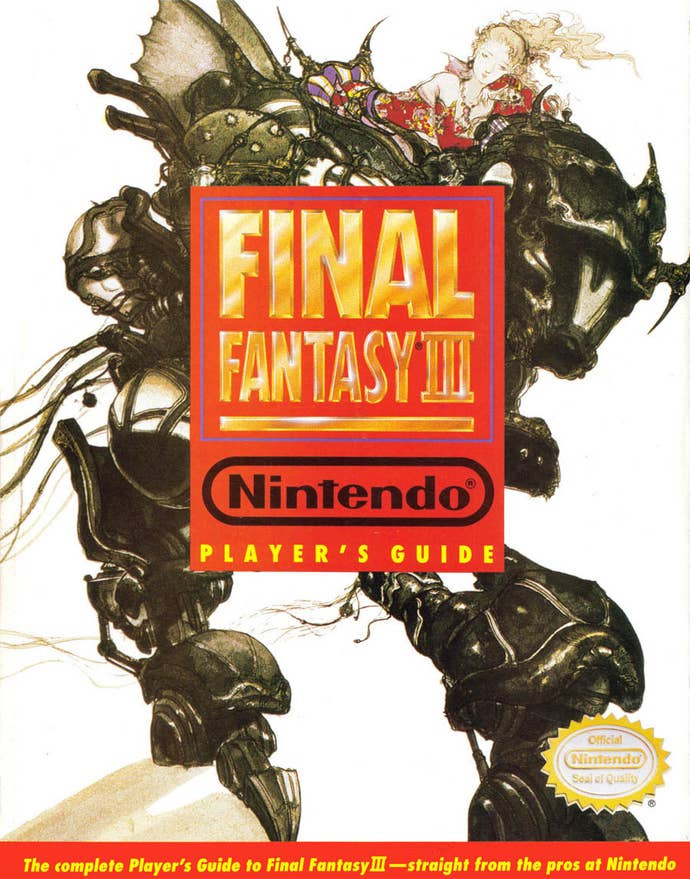

The first time I saw — or rather, noticed — Yoshitaka Amano's work was when I stumbled across the Nintendo-published U.S. strategy guide for Final Fantasy VI, back when we in America thought it was actually the third Final Fantasy.

Until that point, the artwork Nintendo and Squaresoft had used to promote Final Fantasy outside Japan had largely ranged from blandly functional to downright hideous. I mean, Nintendo Power attempted to introduce the Final Fantasy series to America with a special guidebook to the original NES emblazoned with one of the most ridiculous cover images I've ever seen. It sported amateurish renditions of generic fantasy warriors crowded into a comically tiny flying boat, capturing the words of the game — wizard! knight! airship! crystals! — but not the spirit. And then there were the bizarre illustrations the magazine used to accompany its Final Fantasy II (née IV) coverage a year or two later, with hideous interpretations of the game's cast that ranged from turning the hero's frienemy Kain into a musclebound lunk with a thing for bondage gear to rendering pre-teen wizards Palom and Porom as grotesque, Tweedledee/Tweedledum-like abominations.

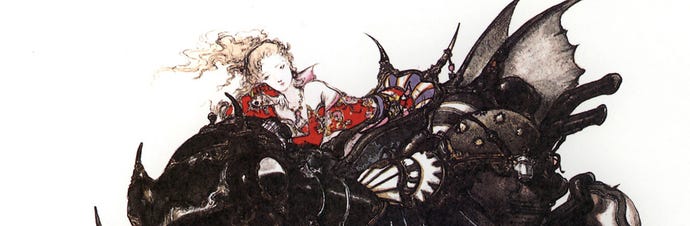

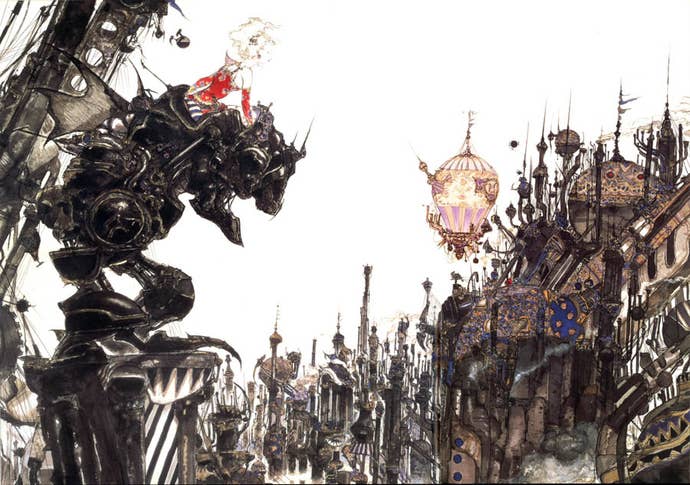

The Final Fantasy III guide, on the other hand, featured a striking cover image. It stood out from shelves by avoiding the hypertrophic musclemen and garish explosions typical to 16-bit American game packaging. In their place instead appeared a delicate, almost impressionistic rendition of a young woman with flowing hair reclining in the cockpit of a gnarled, angular machine. Despite the cover illustration being largely obscured by a huge red block from which the book's title screamed in shiny gold letters, I recognized the subject of the painting immediately: This was Terra perched atop a Magitek Armor, an artistic take on Final Fantasy VI's stunning introduction in which we meet the story's central character as a brainwashed servant storming through a mining town atop powerful armor in service of an imperial army.

Despite having completed two playthroughs of the massive RPG by that point and having little use for a guide, I grabbed the book anyway. A quick skim through the volume revealed dozens of other illustrations in the same style scattered throughout its page: Sketchy, dreamlike pen-and-watercolor images depicting the rest of the game's sizable cast in all manner of elaborate garb and atypical poses. Grieving samurai Cyan Garamonde, for example, didn't appear here clutching his blade, glaring at the viewer, snarling in his lust for vengeance. Instead, he lounged on some sort of metallic surface, one hand on the hilt of his (sheathed) sword, but with his eyes closed and his legs crossed, as if meditating. Martial artist Sabin Figaro sat on a hillside beneath a tree in one image, standing calm as he gazed skyward with a rucksack in hand in another.

What struck me most about these illustrations was just how unlike typical video game promotional artwork they appeared to be. While the cover's bulky armor suit looked intimidating with its sharp angles and threatening pose, Terra herself seemed almost indifferent to the action. It wasn't simply her air of diffidence that set her apart from the rest of the image, though; the artist had rendered her with pale colors and flowing lines, whereas her machine mount consisted entirely of rigid lines and dark tones of brown and grey. The contrast beautifully depicted the nature of FFVI's story and Terra's conflict: The otherworldly young woman shackled to a cruel, oppressive machine in service of an empire seeking to subjugate and exploit both nature and the supernatural.

This was the tail end of 1994, and the World Wide Web was in such a rudimentary form as to be unrecognizable by today's standards. Nevertheless, in the following months, I dug up all the Final Fantasy information that I possibly could through simple fan pages and primitive search engines. In the process, I discovered the mystery guide book artist's name: Amano. I also learned that America's third Final Fantasy game was actually the series' sixth entry, and that Amano had created the Japanese packaging or promotion artwork for all six of them. He was also responsible for most of the series' unique, detailed enemy sprites dating all the way back to the NES game. Discovering Amano and his history with Final Fantasy served as a crucial gateway by which I began to learn more about localization, about games that had been left stranded in Japan, and about the universe of video games beyond American shores.

Few artists share as close an association as Amano and Final Fantasy — though, ironically, the next entry in the series would see the two begin to part ways. While Amano continues to contribute illustrations to Final Fantasy, his role as lead character and monster designer ended with FFVI. Beginning with Final Fantasy VII, Amano's duties generally fell to Tetsuya Nomura, a young illustrator who had provided a handful of monster and character designs to Final Fantasy V and VI and whose crisp, angular art style lent itself better to the chunky polygonal world presented in FFVII's engine. Amano's fluid, ethereal designs worked wonderfully when enemies consisted of static sprites, and it's not hard to imagine a modern 3D game that reproduces his watercolor techniques with advanced graphical shaders... but in the blocky, low-poly world of FFVII and VIII, Amano's work had no place.

This turn of events was by no means the end of the world for Yoshitaka Amano. While Final Fantasy may be his best-known body of work among American fans — and he still contributes to every game in the series, including a massive mural he created for the recent Final Fantasy XV event — his career spans much further than that. Amano has a reputation for experimentation, for efficiency, for an extraordinary work ethic (producing hundreds of illustrations each year), and for his sheer versatility. He first made his name in the ’60s and ’70s as an illustrator and designer for Tatsunoko Productions anime series like Speed Racer and Gatchaman (also known as Battle of the Planets). He's collaborated with innovative creators including Neil Gaiman and David Bowie. He also produces his own fine art works in a personal studio in central Tokyo (ironically located directly across the street from ArtePiazza, a company that has worked on numerous games in Final Fantasy's rival RPG franchise Dragon Quest). I had the good fortune to meet with Amano in this studio several months back to get a sense of his perspective on his own work, and to learn more about his relationship with both games and art.

USgamer: It's great to meet you after following your work for more than 20 years, since I discovered it through a Final Fantasy strategy guide. Of course, you're not as heavily involved in that series anymore — what projects are you working on these days?

Yoshitaka Amano: You know, normally, my work doesn’t see print often, because game creators will use my [concept] artwork create the final art and characters based on that. With strategy guides, though, my artwork sometimes goes directly into the book. In my eyes, it’s probably a rare case that this artwork makes it to the public... sometimes even with character designs that are different from what you see in even the games.

I'd say 90% of the time I spend on creating contemporary art; the remainder I spend on game projects like Final Fantasy, stuff like that. For me, I find my strong meaning when creating contemporary art. Work that I've created for anime or games, that kind of content... that still shows up in my style while I'm creating his contemporary art. So I value both [facets] a lot, and feel they're both very important.

USG: When you say contemporary art, what media do you work in most? Is it painting, sculpture, found art? I’m curious to know more about the projects you work on.

YA: Two examples. First, this is a good example of what I currently do. [Amano gestures to an enormous abstract painting on a sheet of metal to the side of the room] What I'll do here is draw a painting on aluminum, then add a special coating, the kind of coating that cars have, and make it into this kind of art. Normally, when you paint, it’s just this big [Amano makes a small gesture], but I like do huge panels, something this big, or maybe even bigger than this panel. That’s for a flat surface.

I also like to work in media that has a shape which, like this sculpture over here. [Amano gestures to a metal sculpture of a panther-like creature, about three meters in length] I started with clay to make a small model, and then I skinned the 3D data and created this big guy over here. So by using current technology, by blending my art with tech, I'm able to create something like this, and that’s something I'm really into right now. That combination is something I've been trying to express through my contemporary art.