The Famicom Legacy

Jeremy Parish explores the many ways in which the NES continues to affect gaming and gamers 30 years after the system's debut.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

Three decades ago, Nintendo debuted its first home console, the Famicom, alongside several other contenders for control of Japan's nascent home gaming market. A combination of great hardware design, excellent software, canny marketing, perfect timing, and a bit of humble pie helped vault Nintendo into the lead over its competitors.

In less than two years, it was by far the leading console in Japan, racking up sales numbers that rivaled what Atari had accomplished with the 2600 in the much larger U.S. market. But you know that already. Had the Famicom story ended there, Nintendo's classic console would have gone down in history as a fond memory among Japanese gamers, much like its short-lived contemporary ColecoVision has for its small following of American fans. But Famicom's story didn't end there. The system carried on for more than a decade, winding down in 1994 with the masterful Takahashi Meijin No Boukenjima IV (Adventure Island IV). By that point, the Famicom hardware was well out of date, but such was its staying power that countless gamers continued to cling to it well after the system's successor (Super Famicom, aka Super NES) and rivals (Mega Drive and PC Engine, aka Genesis and TurboGrafx) had staked out the industry as their turf.

From that 11-year run, the Famicom's influence rippled outward. And like the chaos caused by the proverbial Chinese butterfly's fluttering, those ripples continue to reverberate around the world as thunderstorms.

Famicom established consoles as Japan's gaming platform of choice

In the early '80s, things could have gone either way in Japan. Consoles hadn't gained much traction; while PCs were expensive, they offered a lot of appeal to developers thanks to their relative power and capacity. Without a front-running contender in the console space, Japan's home games industry could have gone the same way as America's, with the rise of lower-cost game-friendly personal computers giving a home to eager developers.

Famicom nipped that possibility in the bud. Its respectable under-the-hood power and external extensibility (first with a diskette-based add-on, then with special co-processors built into game cartridges themselves) gave it the long, evolving legs of a personal computer. But its streamlined interface lent itself to more accessible and more visually appealing games, which drew in younger players and their parents alike. Complex, text-heavy PC software, on the other hand, tended to throw up natural barriers to young fans.

"Computer games were becoming more complex, their manuals getting thicker, and requiring more dedication from the player," says Chrontendo creator Dr. Sparkle. "The Famicom, starting in the third year or so of its existence, began producing games that split the difference between the two approaches. The Legend of Zelda was the most obvious example of this approach. These games were action-based and had a certain amount of audio/visual dazzle, but were longer, with a less frantic, more contemplative style of gameplay.

"Unlike many computer games, the mechanics were usually completely intuitive. Famicom-original RPGs were able to be played and understood by anyone, as opposed to the opaque and brutalizing style of computer RPGS like Wizardry. This console-specific approach can be most clearly seen by comparing the arcade versions of Ninja Gaiden, Bionic Commando, or Strider with their Famicom counterparts."

The Famicom boom inspired a number of other companies to jump in and try their own hand at creating a console. Even today, the console industry is dominated by two Japanese hardware makers and one American. The lines between formats have grown increasingly blurred, and rumors constantly swirl around Apple and Valve looking to get into hardware, but even so Japanese consoles -- including the Famicom's direct descendants -- continue to give a strong showing.

It resuscitated the U.S. console industry

Japan wasn't the only country to benefit from the Famicom's success, of course. America had practically given up on consoles by the time the Famicom made its way west as the Nintendo Entertainment System. When the bottom fell out of the Atari 2600 market, the entire industry went with it; by some estimates, revenues dropped a whopping 97% in just a few short years. That's why developers and publishers abandoned ship for the safer waters of the computer market.

In doing so, they left the door wide open for Nintendo to swoop in and take over. It wasn't that easy, of course; they only managed to get their foot in the door with a combination of chicanery and clever salesmanship. American retailers didn't want to sell video game systems and cartridges. But a video entertainment system? With game paks? And a gun, and a robot? Well, now, that was a different story altogether!

Naturally, kids saw right through the marketing obfuscation. No one ever called NES games "game paks," they called them "cartridges" or "game tapes" or whatever. And no one bothered to keep R.O.B. set up after their first few disappointing hours with Gyromite, either. What kids wanted was a way to play video games, at home, despite retail buyers' firm conviction that such a thing was completely unsalable. They were quick to realize their error once sales picked up, though. Before long, video games were enough of a force to be allowed to sit at the grown-ups' table, moving at long last from the toys section to electronics.

It made Japanese developers the dominant force on consoles for a decade

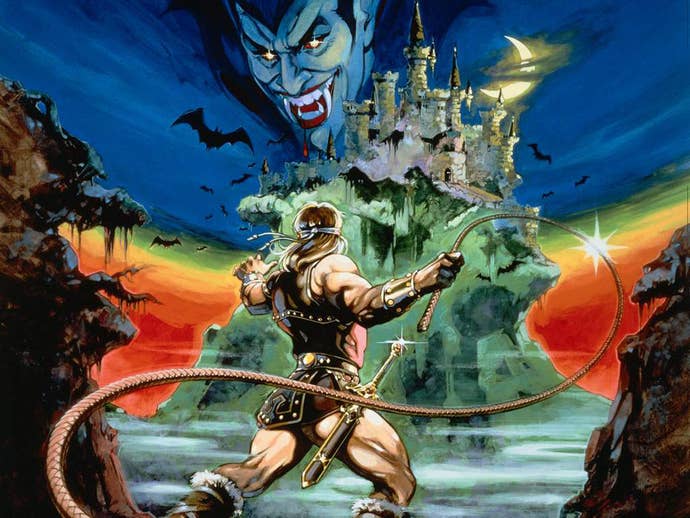

The Famicom's long lead in Japan and emergence into an American industry that had all but abandoned consoles had a significant side effect: It gave Japanese developers a huge head-start on creating console games. By the time the NES gained traction in the U.S., Japanese third parties had been plugging away at the hardware for three or four years.

So, as games as sophisticated as Super Mario Bros. 2, Castlevania, and Mega Man 2 were being imported into the U.S., American developers were still struggling to come up with anything decent. In the end, you'd be hard-pressed to name a single great American-developed title from the NES's library of 700-plus official games (especially since most American developers tried to work outside the system through unlicensed publishers). Most notable Western-made NES games were created by Rare (from the U.K.), and many American publishers contracted with Japanese developers like Atlus to create games specific to the U.S. market, such as Friday the 13th and Jaws.

Western developers gained some traction in the 16-bit era thanks to the efforts of Electronic Arts and Midway, but even then they specialized primarily in sports titles and arcade conversions (as well as the occasional awkward conversion of PC games that properly needed a mouse or keyboard). The more console-specific games still came from Japan. And the international divide between specialization continued well beyond the 16-bit era as Sony supplanted Nintendo as console gaming's de facto powerhouse.

"[The Famicom] transformed Nintendo from a toy company who had several arcade game hits under its belt into a multi-billion dollar corporation with thousands of employees," says Dr. Sparkle. "Nintendo's success directly inspired Sony to enter the video game market, and the end result was Japanese domination of the video game industry for around a 15-year time period. Obviously, the video game industry would look very different today without the Famicom."

It created a viable balance for first- and third-party cooperation

Perhaps the most important feat Nintendo accomplished with the Famicom and NES was to figure out how to let third-party software flourish on the console without completely gutting the market as it had with the 2600. In the Famicom's early days, Nintendo didn't impose many restrictions on third parties, but they quickly began to force licensing rules on other publishers who wanted a bite of the Famicom pie.

By the time the NES launched, Nintendo had licensing down to a science and built their copy protection right into the system. The NES featured a unique circuit, the 10NES, not featured in the Famicom, and licensed NES cartridges included a matching circuit that would cause the console to acknowledge them as legitimate. This gave Nintendo fine control not only over the manufacturing process but also over the quantity and frequency with which software could be released, thus preventing too many games of dubious quality from flooding the market. Not to say the NES didn't have plenty of dubious games; they simply came out at a more measured rate than they had in the dark days of the 2600. The market didn't crater; on the contrary, it thrived.

Nintendo's approach to licensing had some negative effects, however. The company's system was set up to strongly favor Nintendo's bottom line; third parties climbed aboard at their own substantial up-front risk. This created an undercurrent of resentment for Nintendo that still exists and very likely has played a part in the Wii U's soft third-party support. In the more immediate term, gamers found themselves vexed by another drawback: The 10NES chip combined with the NES's cool but failure-prone top-loading design to cause countless control decks to offer nothing but blank, flashing colors when the console's innards became even slightly dirty. Dust (or a slight misalignment of the fickle loading system) interfered with the authorization circuit.

It gave birth to countless beloved franchises

Almost any Nintendo franchise you care about can be traced back to the Famicom. Sure, Donkey Kong gave Mario his start in the arcades, but Super Mario Bros. didn't exist until the NES. And think of all those other major franchises that debuted on the NES: The Legend of Zelda, Metroid, and (to a lesser degree) Kid Icarus. Plus, Nintendo had plenty of series that got their start on Famicom but didn't make it to America until later, such as Fire Emblem, EarthBound, and Advance Wars.

And let's not forget the third-party juggernauts. Dragon Quest and Final Fantasy began on NES, as did Castlevania and Mega Man. Resident Evil may not have shown up until PlayStation, but its direct inspiration -- Sweet Home -- was a minor Famicom hit. The Shin Megami Tensei series, The Glory of Hercules, Ninja Gaiden, and plenty more also owe their existence to the NES and Famicom. Certainly these games could have appeared on any platform, but together they created a sort of critical mass that helped burn them into the impressionable young minds of millions of NES owners. Great things came from Famicom's ability to roll up talented developers like a silicon katamari.

It left Japanese devs unprepared for the move to PC-like consoles

But let's not make the mistake of acting as though everything the Famicom wrought was necessarily for the best. In some ways, you can blame the system's developer culture for the challenges Japanese developers have faced over the past decade. Where once the majority of essential console games came from Japan, today only a handful of major console franchises are the product of Japanese talent; by and large, the nation's developers have shifted their attention to portable systems and, increasingly, mobile games.

Because their efforts initially focused so heavily on consoles, the console market's shift to PC-derived structures put Japanese developers at a disadvantage to their Western peers, who had of course shifted their attention to the personal computer back in the '80s, when Japan claimed squatter's rights on the vacant American console market. PCs and consoles existed in parallel for two decades, but when they at last converged their architecture -- and thus the skills required to properly master the machines -- hewed closer to the PC's innards. (The exception to this rule, the PlayStation 3, was regarded as difficult to develop for by creators on both sides of the ocean.)

Furthermore, this change in the fundamental thinking behind console hardware came hand-in-hand with the move to more demanding HD development. Japanese studios, more accustomed to handling all aspects of development internally, found themselves overwhelmed, over budget, and behind schedule with big-ticket titles like Final Fantasy XIII and Metal Gear Solid 4. (One rumor surrounding MGS4 back in the day suggested that everyone at Konami effectively stopped what they were working on for a few months to pitch in and help get the game out the door, and the presence of names from completely unrelated internal teams such as Silent Hill and Castlevania in the credits would seem to bear that out.) Western studios, on the other hand, were able to take a realistic look at their workload and outsource material as needed.

Of course, the reasons behind this paradigm are complex and cultural. But you can nevertheless trace the Japanese game development workflow back to the Famicom days, when most studios established their practices and standards. Is this Nintendo's fault? Not at all. But recently, NCL president Satoru Iwata has indicated the move to HD development on Wii U has caught Nintendo's internal teams flat-footed as well. Apparently learning from history is something only the other guys should have to do.

Famicom shaped the tastes of a younger generation of game designers

On the flip side of this, the Famicom and NES libraries have exerted a tremendous influence over today's crop of aspiring game developers. The indie game scene is thick with young creators who cut their teeth on NES games. Certainly the NES isn't the only influence at work in the scene -- far from it -- but the design and aesthetics of Nintendo's 8-bit era continue to churn to the surface of new and innovative games in surprising ways.

Among the earliest NES-inspired indies were 2004's Cave Story and 2007's I Wanna Be the Guy: The former reworked the concepts of classics like Metroid into a wholly new experience, while the latter took a more Dadaist approach by deliberately mashing graphical elements stripped from NES games into a retro-inspired platformer that deliberately and subversively twisted player expectations at every turn. Eventually, that same philosophy made its way to "real" games, such as 2008's Mega Man 9: A legitimate sequel to the long-running series that reverted back to the graphics and play style of the NES games.

Games as diverse as Fez, Odallus, and Axiom Verge demonstrate a marked influence from the NES to different degrees. Countless others as well. This trend isn't the result of creative bankruptcy or game designers allowing nostalgia to overcome their good sense, but rather a way for creators to pay tribute to the works that set them on the path of game development. And on some level, it's also a recognition of the fact that dated technology and limited visuals have a material impact on game design. The Famicom remains a viable canvas for creative work, and it's interesting to see how people approach it with the benefit of hindsight and free of the processes and constraints under which games used to be designed.

And finally, it fueled 30 years of dominance by Nintendo

Whether you love or hate Nintendo, the simple fact of the matter is that the Famicom's success set them up to be one of gaming's most consistent, dominating forces. Emboldened by their 8-bit console successes, Nintendo soon followed up with the portable Game Boy system. Even as their console dominance waned in subsequent generations, the Game Boy and its successors have remained at the top of the portable gaming heap for nearly 25 years.

While other platform manufacturers have come and gone - Atari, Sega, NEC, and others -- Nintendo has remained steady through the years. And there's no denying that their empire has been built on the bedrock of the Famicom. Their killer apps and system sellers belong to franchises with Famicom roots, and regurgitated fragments of Famicom games bob to the surface of their products all the time. From the maniacal flashes of NES games in WarioWare to swappable Famicom ephemera in Animal Crossing: New Leaf, Nintendo forever stands tall on the Famicom legacy.

Whatever path Nintendo chooses to take in the coming years, you can be sure that memories of the Famicom will be at the vanguard. Three decades after its debut, Nintendo's 8-bit console classic remains as essential as ever.