The City and the Sea: The Story of Failbetter Games

Eurogamer's Chris Donlan asks: "Do you know the way to Shell Beach?"

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

What's the most important video game location? I think it's Shell Beach, which isn't actually in a video game at all.

It's in a movie, Dark City, directed by Alex Proyas and written by Proyas, David S. Goyer and Lem Dobbs. And -- hold onto something -- if we're being completely truthful, Shell Beach isn't really in Dark City either.

Shell Beach is a memory -- a false memory, which means, I guess, that it's ultimately more of an idea. It's the place that the amnesiac hero of Dark City associates with his youth, with his happiness. It's the place that will hopefully give him some kind of clarity after he awakens in a strange midnight metropolis without exits, and finds himself pursued by pale-faced villains clad in black suits. As those last details might suggest, Dark City is rather genre-locked as movies go, squeezed between science fiction and throwback detective flicks. Shell Beach elevates it, though. It's everywhere and nowhere in the film. It's a stop on the train lines where trains themselves never stop. It's a bright 2D spectacle constantly changing size to fit your line of sight -- huge and glossy on billboards, tiny and faded on postcards, lurid and over-exposed in old family photographs.

"There's this point in Dark City where they're finally about to knock down the wall to Shell Beach," remembers Alexis Kennedy. "And I suddenly realised I had literally no idea what was on the other side. That almost never happens in a film. If the whole film had been like that, it would have been very frustrating. Earlier on there's the chase scene where the buildings are changing shape and the hero starts to question his own sanity -- that starts to get dull because there's nothing to push against. But that scene with the wall is wonderful." He laughs. "The stuff we're interested in isn't typical film student nonsense where it's just randomness for random's sake. It's the stuff where you have enough references to navigate by but you're genuinely unsure what territory you're going to end up in." Shell Beach, then: the promise of games and of fiction in general. Hinted at, mistily invoked, and often snatched away before it resolves into something tangible. After all, Shell Beach doesn't really work when you actually get there, just as you can never reach the horizon and then stomp around on it.

Kennedy -- and his collaborator Paul Arendt -- are the driving forces behind Failbetter Games, a luxuriously unusual UK development studio that has spent the last few years making "a careful living" by exploring spaces just like Shell Beach. It's an unashamedly literary outfit, fascinated not just by fiction but by the gaps in fiction that allow the audiences' imagination to creep in and fester. Failbetter's also, to echo Kennedy's earlier phrase, got more than enough references. Isn't that inevitable? Failbetter's main opus, the online interactive fiction adventure Fallen London, is primarily a gothic experience, and Kennedy describes gothic fiction as a "robber prince". "It's not just a kleptomaniac," he says, "it steals from everything. And so we get to steal from everything and get away with it."

He's not kidding. Over the course of an hour long chat, you'd be amazed by what comes up in passing: Poe, Dickens, Melville and Stevenson, but also Tarkovsky, Lynch, Kubrick, Raiders of the Lost Ark, Jack Vance, Ellen Raskin, Chris Ware, The Nine Lives of Tomas Katz. And the facts! You never heard such facts! When I learned that Failbetter was based in Greenwich, I thought of Fallen London, with its subterranean metropolis, its grimy golden-brown bricks, its marks and magicians and night circuses and dancing fleas and I thought: "Yeah, Greenwich would work for them." But I was imagining the old town -- the steeples and maritime pubs and the dark shops selling bathyspheres and sextants and other bronze finery. In fact, Failbetter's located on the Greenwich Peninsula, in a busy new tower block overlooking what was formerly known as The Millennium Dome, where chain restaurants pump out cheesy pop music to an audience of precisely nobody; where Lady Gaga loops and stutters on video screens three storeys high, and where Esso or Emirates might get away from the office for team-building.

And yet it's not as ill-fitting a location as you might expect, apparently. That is to say, so long as you know the facts. "Views of the Dome are not what people think of with us," says Kennedy, "but the Peninsula is a fascinating place. It's been populated, like most of London, for thousands of years. It was a haunt of ne'er do wells and river pirates. They dug up the skeleton of a whale on the beach." He looks it up for me. "A North Atlantic right whale."

Oh yes, and the reason that there's all that empty space out there on the cusp of the London Underground's Zone 2 is that the gasworks here once contaminated the entire peninsula with carcinogenic tar. "For years it wasn't safe to build on," Kennedy enthuses. "In the end, they peeled off the topsoil, laid a giant plastic sheet over the peninsula, and then shipped in new topsoil and built on top of that. I live just over there in one of those orange blocks and there's a clause in my lease that says I'm not allowed to dig below a certain depth. That's a very Fallen London theme -- this creeping black goo kept in check by a peninsula-sized condom."

"Still," says Arendt, casting an eye about the room where we're chatting, lingering over reimagined wingbacks upholstered in furry material dyed highlighter-pen yellow. "We ought to have a slightly dank dripping basement somewhere with high desks and so on."

Failbetter Games was founded a few years back by Kennedy, an English teacher and software developer who wanted to be either a writer, a games designer, or both, and Arendt, a journalist who wanted to be an illustrator. All of their wishes came true. For a while, the company was going to be called Buzzkill Games, and then Kennedy remembered a quote from Samuel Beckett: "Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try Again. Fail again. Fail better." What a neat little dance of thought, taking you up and down at the same time; optimism and pessimism -- fatalism -- converging in a few short hops.

"Failbetter is just that iterative thing, or at least that's how I took it," Kennedy tells me. "Although, years later I read another piece of commentary that suggested that Beckett was not so much saying, 'Try, try again and eventually you'll succeed,' but rather: 'You're going to keep failing so get used to it.'" I get the impression he still would have chosen the same quote had he known.

Naming the company may have been a tricky and ambiguous business, but Kennedy at least had a sense of what he wanted to do with it. "I played Baldur's Gate, like many people of my generation, and I was blown away by the fact that it was suddenly like being in a fantasy novel," he says. "You had this backstory that's really simple but that really works. You're brought up in a remote monastery and you discover that you've got a strange and a terrible heritage. Wow! You play through the prologue and it's all so exciting. Now you're going to kill some Kobalts for four hours -- now another bit of story. That was all fine, but I just thought: wouldn't it be awesome if you had a game that was all story, with that sense of progress and basic choice?"

In Kennedy's head, a structure was starting to suggest itself: little chunks of narrative, tied together in a way that suited the player. From a cancelled Twitter game project he got the idea of a setting, too: a gothic world -- a buried world! -- filled with dark, thrilling possibilities. "When I was trying to explain it to Paul and explain the context of it, he said, 'I don't understand what this thing's about at all.' We fell back on it being London translated underground. As soon as it had an actual location it started to work."

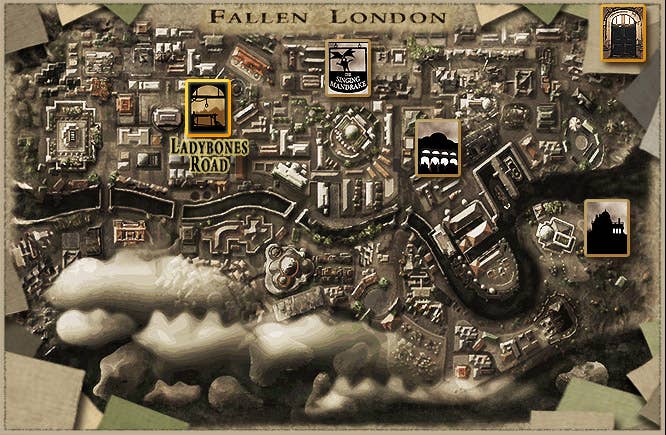

The game that steadily emerged from this was Fallen London, initially called Echo Bazaar. From your roost in a prison cell overlooking the city, you break free and then blend in. You find rooms, maybe in Ladybones Road, which favours the watchful, you learn abilities and take pleasure in your expanding options. Along the way, you embark on numerous adventures described with a Victorian sense of precision, economy, elegance and cheerful wit. There's PvP of sorts, romance, and an energy mechanic holding you back from splurging, but the whole thing's delivered with such generosity you'll rarely need to know about it. "We're not very good businessmen," says Kennedy. "We're just too f**king polite." All told, Fallen London's a musty, creaking netherscape waiting to lure you in from a buried browser tab -- a city of words, but not words alone.

"Paul came on board because I wanted to write and code but I can't draw," says Kennedy. The original plan was to pay Arendt outright for his illustration work. "I said, 'I want to pay you as I want this to be a professional thing.' He said, 'Cut me in for a percentage,' and I said, 'Sure, that's great! I don't need to give you any money now! But you realise we're probably not going to make any actual money out of it?'" He claps his hands together. "We've been on salary for three years now, so... so that worked out."

Playing Fallen London is a strange, fascinating business. I'm clicking through my decisions, sure, and watching as the meters go up, but the real pleasure of the game -- the real progression -- lies with something that's a little more interpretative in nature. I'm reading Kennedy's text and looking at the self-contained, evocative Arendt art that accompanies it, and I'm trying to fit them both together and make sense of what emerges. Was this always part of the plan?

"It would be a fallacy to think that we had it all scoped out," says Arendt. "I was essentially a hobby artist at the time, working part-time at the Guardian and just doodling stuff. I really had no idea of the demands of producing assets for games." The duo had to learn as they went along. And, as a result, Arendt admits Fallen London's stratification is rather weird at times. "Look at the Jurassic or Cretaceous layers of illustration styles which slowly become more advanced and then noodle off into mad painted stuff and then finally settle down," he says. "Half of the old ones are all still in the game. Then every now and then I have to go back and delete some of the ones I hate the most."

And once text met illustration, did the project change because of the interaction between them? "Yes, and this has only become more so," says Kennedy. "Initially it was very directed and there was a lot of: 'Can you draw somebody who has these attributes, who does this or that?' So first what I had to learn was not to say things like, 'Can you draw somebody with a troubled past?' because that's not a useful piece of art direction. Also I learned to avoid telling Paul to draw hands because that made him grumpy."

Over time, however, the balance has shifted somewhat. "More of Paul's direction has leaked into the game," smiles Kennedy. "He'd draw things that were subtly different to what I had intended or more experimental. That fed back into the world. For Sunless Sea, our new project, it's really begun to go entirely the other way. There are some concept pieces he's drawn that I've then put fiction around. And there's a lot of things where we'll go back and forth on how something looks. I'll explain how the fiction works and Paul might say that that's not visually interesting so could we do this instead? That wouldn't have been possible at the beginning but now we've been soaking in a marinade of Fallen London for four years, so we're able to do that."

"I'm delighted by the use of the word 'leaked' there," says Arendt who does actually seem genuinely delighted. "I think it sums up a lot of the comedy-yet-serious-yet-comedy creative tension we have about words and pictures. We have a long-running joke that pictures are better than words, words are better than pictures." He pauses and frowns. "Part of that is the purest fear that an image fixes that image in the imagination. It's the Jack Nicholson effect -- you can't read Cuckoo's Nest now without seeing Jack Nicholson."

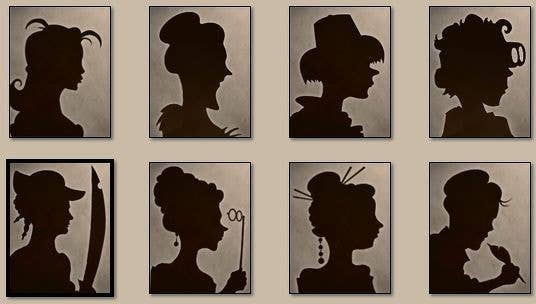

Can illustration actually damage the player's writability of a game's fiction, then? "Absolutely," says Kennedy, sitting forward. "A lot of the art I love, and I mean film, poetry, fiction, is all about something that doesn't quite gel or doesn't quite concretize. The whole point of poetry is that it allows for a strong degree of self assertion, interpretation." He and Arendt nod to one another. "One of the things about Fallen London is that, as a player, you have a lot of gaps to decide what is going on and what your response to things is. We explicitly leave things open for you to do that. But, that said, my favourite film-maker of all time is David Lynch, and that's his whole deal -- not to come to the point, to leave you thinking. Yet those films of his, they're so visual. So especially given that a lot of the most beautiful art Paul does is silhouettes, I think some of my fear of that was naive. I've recanted a bit."

So we're back at Shell Beach? "So much of it's accidental," says Arendt. "Things that arrive by necessity have become core ideas. One of the big ideas that hides underneath the surface of Fallen London is the Tarot. We're a card-based game so it fits, but the truth of the matter is that there's one artist and there are a lot of stories, so for a long time we didn't have enough images to give everything an individual image. If you were a big budget developer, you could say, 'Okay, every story has its own illustration,' but we were working from a slowly increasing pool. So you'd often find yourself in a situation that didn't have an obvious image to go with it. What we found was that if you put with that an image that's wildly inappropriate, it sets off this interesting creative tension.

"We briefly used it as a brainstorming thing for a while," Arendt continues. "We had a deck of images and we'd throw them up to see if they sparked anything. It's fruitful. And the concretizing thing we spoke about, that works both ways. For instance, we had a character who was this really unpleasant slimy guy. In that case, Alexis had a vague idea of this character being a slimeball. I just drew the slimiest character I could think of -- based on old Toht from Raiders of the Lost Ark -- and then Alexis saw the picture and suddenly knew how to write the character."

Throughout my hour or two spent at Failbetter Games, there's an understanding, often openly expressed, that the outfit makes games for an audience that, while committed, is fairly small. "We've been through some lean times," says Arendt at one point, and he acknowledges that it's not hard to see why. Fallen London's a rich and dazzling game, but its richness and its dazzle come, in part, from how specific it is in the things it wants to do. The delicious friend -- the phrase, covered in velvety menace, that's often used when Fallen London addresses the player -- is not just anybody. There might not be many delicious friends out there all told.

This is why it was such a wonderful surprise when Failbetter turned to Kickstarter in September of last year and asked for £60,000 to make Sunless Sea, a new game set within the Fallen London universe. And it's why it was such a wonderful surprise when, a month later, the Kickstarter wrapped up having almost doubled that amount. I ask Kennedy whether he thinks the reason that players are so committed to what Failbetter does is because of the game's ambiguity and the writability this allows for. Are most games so emphatically complete that there are fewer opportunities for people to start building a sense of ownership into them?

"Yes!" says Kennedy. "There's two terms we use, one I stole from Tom Chatfield, who talks of these underspecified narratives that leave gaps. One of the first examples we thought of is fires in the desert. If you think of the whole story as a desert seen from above at night with campfires twinkling out of the darkness, then the explicit bits of the story are the fires, and when you see them you understand them and you know what they're doing."

But, he continues, when players are taking a path between the fires, the players are no longer visible -- the game designer can't see which path they're taking. "You don't know what they're doing out there," he laughs, "and that part belongs to them. With the Kickstarter, I found it a little bit jarring the first time a backer said, 'We're going to make it!' You're going to make it? Then I realized, oh yeah, we are. That's the whole thing. We have a very passionate fanbase for such a small franchise. You expect to see cosplay for BioWare games, you don't expect to see cosplay for something of this size, but you do."

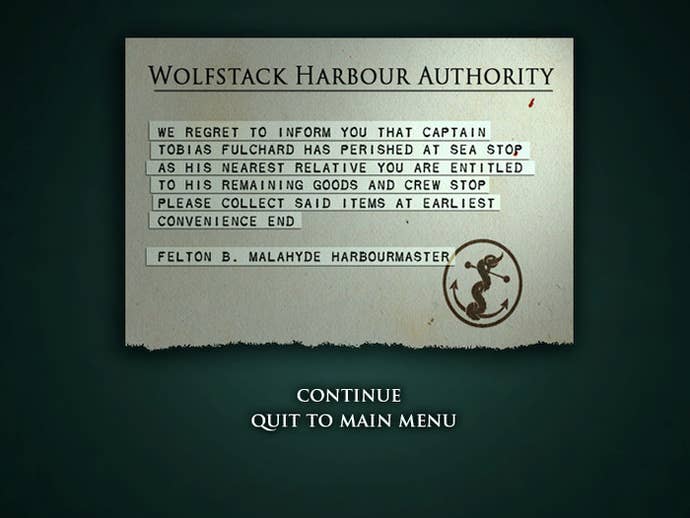

Sunless Sea itself is a wonderful prospect: a game of exploration, loneliness, risk, adventure and madness taking place across a vast subterranean ocean riddled with islands, with dangers, with dripping trophies of the deep. I inevitably want to say it's much more of a traditional video game than Fallen London -- it's top-down and feels in tune with things like FTL and even The Curious Expedition -- but it promises the same lure of the unknown that the team's always traded in. A wrought iron buoy bobs on an Absinthe-green tide. A single light shines out of the murk and the gloom. Battle monsters, says the trailer. Lose your mind. Eat your crew.

"We wanted to take Fallen London elsewhere," admits Arendt, sounding almost guilty. "Because, for all its appeal, it's built into its own niche and we decided, after some heart-searching, that what people cared about was the world rather than the game."

"Yeah," agrees Kennedy, "and so we decided, we want to take the world somewhere else. To do something else with it. What format would that look best in? We looked at the possibility of something like Ascension, a card game which I was playing a lot of at the time. The thing about card games is they look easy to design, but obviously they're not. We talked about a lot of possibilities, and what we found was that we had a kickass audience research tool built into our game."

With typical fourth-wall awareness, Failbetter sent an interfering urchin out onto the streets of Fallen London where he knocked on players' doors and asked them to take part in a survey of sorts. "He had an imaginary suitcase," laughs Kennedy, "and he said, 'Which of these things in the suitcase would you pledge for a Kickstarter for?'" Nobody liked the card game, while short stories and a comic were relatively popular but also hard to make economic sense of. "The 2D top-down Elite-style 'explore the Sunless Sea idea' was just an afterthought," says Kennedy. "But people went for it, limited and sketched out as it was. That's where we came in."

And if Fallen London is still primarily driven by text, the Sunless Sea has had far more visual concerns from the very start. "The key factor was light and dark," says Arendt. "Our original idea was like a map that you wandered around and had stories and adventures in. I was drawing really rough concepts of stuff and we got talking about how you'd actually be able to see -- it being sunless. We talked about spotlights and fog of war, and out of that came the idea of dispelling the darkness actually being a mechanic."

"There are gameplay loops in Fallen London but you have to hand-tool them every time," says Kennedy. "All that stuff's handbuilt. Suddenly being able to generate narrative effect out of mechanics? Lovely! This thematic thing of there being light and dark, for example: you're clearing a fog of unknown and that's what people expect, but also given that it's a game about exploring, we wanted to reward the pleasant bubble-wrapping pleasure of clearing the landscape. It will ultimately gain you secrets that plug back into the game economy and allow you to improve your stats."

The interplay of light and darkness also ties into the combat system, which Kennedy admits owes a lot to FTL. "Obviously shields make sense in this mechanical concept," he says, "but that was more steampunky than we wanted. So what we had in the end was illumination, a kind of reverse shield, a sort of debuff." In Sunless Sea, you'll have to light up your opponent before you can damage them, and your core ship stats all loop into this -- your mirrors abilities are about increasing your opponent's visibility, for example, while your veils are about reducing your own.

"There's fruitful convergence everywhere," says Kennedy. "Sort of analogous to the words and pictures convergence, and it's between starting with a theme, expressing it with mechanics and seeing the mechanics then enrich that theme."

"And it's not just tied to the narrative or the combat," says Arendt. "Just the idea of venturing out into the darkness has become a very core part of the game -- not knowing what's around the next corner, not knowing whether that light in the distance is a monster or a port."

Since starting work on Sunless Sea, Arendt's been studying other games that make use of darkness as a mechanic. "I've noticed that the games that use it tend to use it very carefully," he laughs. "Don't Starve is a good example. It will turn the lights out on you, but for a very limited amount of the day. And because our game is essentially dark all the time, we've had to decide how much of that is about mood and how much is about gameplay. What we're getting to is that the effects of light and shadows and sudden reveals are more useful to us than actual darkness."

"Darkness is the absence of feedback," suggests Kennedy, "and feedback is sort of the key to a game. Also, though, you can blind people with feedback -- the kind of jet-fighter effect." What the designers eventually realized took them back to the interaction of text and images again: the word light needed to be broken out into about six different terms. "There's the light your ship emits," says Kennedy, counting on his fingers. "There's the ambient light of the game. There's the fog of the unknown. There's the temperature around your ship -- the gloom level that is how fast your crew's despair will rise. All of these things we were casually referring to as light, and it turned out they were all different."

Sunless Sea is not yet finished, but I sense it's been a transformative experience for Failbetter. If nothing else, Kennedy admits that he's finally stopped introducing himself as a writer at parties and started introducing himself as a game designer instead. "Because I felt like there was more game design involved now," he explains. "I always wanted to do story and game design. I sit down to write and I feel the game design itch. I sit down to do a design and I feel the story itch. Fallen London, I flip back and forth between satisfying those itches, and there is generally a discipline to each. I plan out a chunk of content, and that is mostly game design stuff. Then when I'm writing the content it's a writing frame of mind. The two are less different than plumbing and, oh, let's say physics, but they're still fundamentally quite different activities and it feels like an act of mental agility to flip back and forth between those two things. They feel like things that sit alongside each other rather than things that are quite fused.

"It's very strongly swings and roundabouts," he laughs. "The swing with Sunless Sea is that suddenly we have to think about all this stuff like the scale of the map. The roundabout is that, oh my God, players consume Fallen London content so quickly. I'll spend a week building something and that's including all these careful checks to stop them gobbling everything up all at once. To go into a game where there's a core loop, and you get the story in in-between times, suddenly there's room to breathe between writing content."

Looking ahead, there won't be that much room to breathe between writing, however. Failbetter's just announced a mysterious gig working with BioWare -- the studio whose Baldur's Gate first turned Kennedy on to the narrative potential of the form -- although they can't talk about it yet. Elsewhere, while attempts to transform Fallen London's StoryNexus platform into a kind of Unity for interactive fiction may not have worked out, Fallen London itself continues to need careful tending and upkeep. Its growth has been extraordinary, in fact. Over four years, this city of text and pictures has gone from being 8,000 words big to more than a million.

So many stories, so many choices. "Ultimately, what gives people ownership of Fallen London is the illusion or the actuality of choice," says Arendt, returning to a favourite topic just before I head off to the Tube. "It's something we have to be very careful with. When you give people three options, they start to feel it's their story."

"Like with the Contessa!" says Kennedy, sensing there's room for one last tale. "This was a very controversial storyline in early Echo Bazaar, back before it was Fallen London. It was a Big Sleep pastiche. You are tracking down a missing contessa and you discover that she's been taken away by her lover, a clay man, who's gradually transforming her into a clay statue so they can be together forever. You're down there in the clay warrens and he's droning on that they're going to be together forever, and you can see her green eyes staring back at you." That's the only clue you get, apparently. It's not clear whether the situation is consensual or not, and you're told, delicious friend, that you can either walk away or smash the statue to pieces.

If you smash the statue, you leave the clay man howling over the contessa's remnants as you depart. If you walk away, you end up thinking: perhaps it's love? "There's no option to rescue her, because that's not what that story was about," says Kennedy. "It's one of those where you turn up after the ending. There was a separate issue with whether it denies the female character in the story agency. Yes it does, but there are enough other female characters with agency in Fallen London that sometimes you just end up in the wrong place at the wrong time. But the basic thing of it, the basic controversy, was that there's no good ending here. It's which bad ending do you choose? That enraged people initially."

He and Arendt both laugh, thinking back at the situation, at the strange, scary things that can happen in a subterranean metropolis formed of shadows and spite. "I said at the time it's bad game design but good poetry," concludes Kennedy. "And you have to go with the poetry."