The Case of the Disappearing Video Games

Eurogamer's Simon Parkin asks: does it matter when a medium's past begins to disappear?

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

61 video games have been 'delisted' from Microsoft's Xbox Live Arcade service to date.

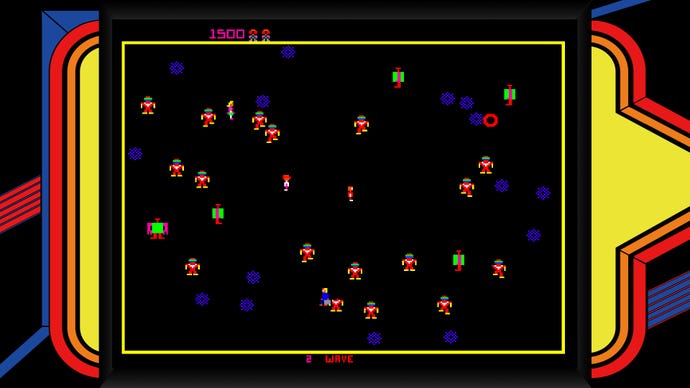

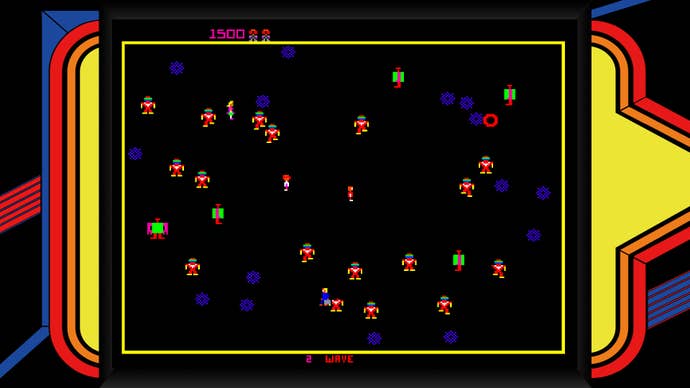

Some, such as the recreations of pithy 80s arcade games like Defender, Robotron 2084, Double Dragon and Gauntlet are readily available to play in compendiums elsewhere or, if you've the budget, on their original cabinets. But others, such as Microsoft's experimental virtual game show 100 vs 1 or Sumo Digital's elegant tribute to arcade racing games OutRun Online Arcade or Double Fine Happy Action Theater (a game designed by Tim Schafer as a way for his two-year old daughter to interact with a TV screen) are no longer available to buy anywhere. These video games may be lost forever in the ebb of digital distribution's uncaring tide.

Microsoft is evasive on the reasons behind the disappearances. Pressed on the issue a spokesperson provided the following tepid statement: "We work closely with our development partners to ensure that gamers have access to great titles through Xbox Live, which sometimes includes the removal of content due to expired rights and licensing or other circumstances specific to developer/publisher terms." Expired rights and licences limiting the sale of video games is nothing new -- it's one of the reasons that we're yet to see a re-release of 1997's seminal, James Bond tie-in Goldeneye 007. But in the past, a licensed game would remain available to buy on the second hand market. In the digital age, there is no physical artefact. Once it's removed from sale, it's gone without trace.

Indeed, while these 61 games remain on Microsoft's servers (anybody who previously bought one of these games and deleted it is currently still able to re-download the game), the moment those servers are shut down, a great swathe of video game history is wiped away. Where once we could place our treasured games and memories in cardboard boxes and store them in attics, increasingly video games are ephemeral things, fleeting and formless.

"It's a big problem already, and I suspect it's going to be even bigger 20 years from now when historians find themselves unable to experience significant works like World of Warcraft."

Frank Cifaldi

Frank Cifaldi is a self-professed video game archivist and historian. He runs Lost Levels, a website dedicated to unreleased video games. But he also has a special interest in digital games that made it to market but are no longer available to buy. He works for the studio that made War of the Worlds, one of the disappeared titles on Xbox Live. "It's a big problem already, and I suspect it's going to be even bigger 20 years from now when historians find themselves unable to experience significant works like World of Warcraft," he tells me. "We're always going to be able to approximate the experience of viewing Birth of a Nation the way it was originally intended, but we don't have a solution for how to recreate games that require not only hundreds of active players, but the proprietary servers that may no longer exist."

Some might argue that the deleted games hold little significance: primarily comprised of dated sports games and barely concealed advergames. But for Cifaldi it's not just an issue of not being able to preserve games that are considered culturally significant today. "The maddening part about preserving video game history is that we just don't know what's going to be important 50 years from now," he says. "Art -- especially risky, forward-thinking art like games -- has a way of going unnoticed when it's contemporary and discovered years later. For all we know we're still in the silent movie age of what interactive media is evolves into. If we're not hanging on to every scrap of our history now, we're going to inevitably lose things that could benefit society in the future."

Henry Lowood is curator for the history of science & technology collections and film & media collections in the Stanford University Libraries, where he works to preserve and archive video games. He is optimistic about the work being done to save our games. "In terms of the technical means for preserving software, cultural repositories such as museums, libraries and archives are making great progress." Stanford University Libraries acquired its first major historical collection of software more than 15 years ago. "Since that time, we have been working on a variety of problems related to software preservation such as cataloging, data migration and access," he says. "We have developed a digital repository capable of storing and preserving software and many other forms of digital information and artifacts."

But there are many problems unique to preserving contemporary digital video games in libraries such as Stanford's. Online activations, authentications and online gameplay modes that require active servers in order to work make storing working copies of games almost impossible in some cases. Then, of course, there's the problem of obtaining code for video games that only exist in digital form. "When access to digital-only software is cut-off the likelihood that particular software title will be lost permanently increases," says Lowood. His work at Stanford involves attempting to convince publishers and rights-holders to discuss possible ways of archiving their games. Unfortunately, while a few publishers willing to engage in conversations about how to preserve games, Lowood states: "Many are not".

"We risk ending up in a 'digital dark age' because so much material that defines our current era immaterial and ephemeral."

James Newman

The situation is compounded by the fact that many developers fail to keep master copies of their own games. "One of the scariest unpublished truths is that video game developers and publishers are, on average, kind of bad at hanging onto their source code," says Cifaldi. "In theory, a game can live forever as long as its source code is safe and able to be compiled. It's like having the master print of a movie; the film stock it's on might not be usable anymore, but it can be transferred to a new format. If I had it my way, providing source code would be a requirement when submitting a game to the Copyright office: that way, no matter what happens, we know that someone has a copy."

There is, however, another way. All 61 de-listed XBLA games are available for download on bit torrent services, where they've been pirated and made available to play on a hacked console. Some believe that piracy is our best current form of video game preservation. But even piracy cannot be entirely relied on. For multiplayer games the require active servers, preserving the experience once those servers are shutdown is near impossible, while pirates copies do not archive the various iterations of some contemporary games as they are modified week to week by their creators. "It isn't like the old days where creators would finish a game, burn it on a disc, and call it 'final'," explains Cifaldi. "Games evolve on the fly now. FarmVille is one of the defining games of the early part of the 21st century. But it is a game that was updated constantly. Can we recreate the game's evolution and see what Zynga learned as it went? I'd wager not."

James Newman is a senior lecturer in media and cultural studies at Bath Spa University in the UK, and the author of Best Before: Videogames, Supersession and Obsolescence, a book that investigates the issues and challenges of video game preservation. "The common phrase used in preservation circles is that we risk ending up in a 'digital dark age' because so much material that defines our current era immaterial and ephemeral," he tells me, with foreboding flourish. "Unless we do something, our ability to document the period in which we lived will be significantly reduced."

For Newman, the problem that many video game archive projects face is that it is almost impossible for people to bequest digital-only games. "In a world of material objects, it is comparatively easy to donate objects to museums, collections, libraries," he says. "In a world of digital assets, it isn't just hard, it is often impossible -- both technically and legally. Read a video game's EULA and often you find that 'your stuff' often isn't 'your stuff' at all. You might own a license to use it under certain conditions, but even if you could find a way to transfer the data, it often isn't yours to transfer."

"We would want to see the games being played by people who understood them, hear their developers talking about them, see the art, stories, costumes that fans made and watch the Let's Play videos."

James Newman

This problem isn't unique to games. Many libraries face similar issues in relation to e-books. Newman, however, believes that there are other workable and arguably more valuable ways of preserving our video game heritage. "If we think the purpose of game preservation is to keep games playable forever then we should try to capture code, emulate systems and plead with publishers not to delist or deactivate servers. But if we think about the period of time in which a game can be played as being finite and recognise that at some point in the future the game might not be playable either because it is inaccessible or all the Xbox Ones have worn out, then the thing we really need to do is document this moment."

For Newman, documentary, not maintenance is the long-term solution. "For me -- and this is where I am probably going out on a limb in relation to some of my colleagues who work in game preservation -- the key is to stop worrying about stuff not lasting forever or games not being playable in hundreds of years time. They are playable now so we should celebrate and, most importantly, document that fact. Even if we could make everything playable forever, what would it mean to be able to play the games of today in 200 years? At the very least, we would want some context. We would want to see the games being played by people who understood them, hear their developers talking about them, see the art, stories, costumes that fans made, and watch the Let's Play videos."

Newman describes this as a shift in focus from 'game preservation' to 'gameplay preservation'. "Once you think about game preservation as a documentary activity the problem shifts a bit. You move from questions about ensuring long-term access to games that publishers want to switch off, to attempting to make available design documentation and discussing the process of game development. For me, working with developers and publishers in this way seems more potentially fruitful than trying to fight the fundamental business model of an industry whose continued existence is predicated on new titles and new sales."

While Newman's stance is provocative and divisive, he isn't fundamentally opposed to the idea of trying to keep games playable. He views the documentary work of archivists as working alongside those of game preservation: both are important. "I sometimes think of it in terms of preserving music," he says. "Having a piano in your collection is one thing. Maybe it's a special piano owned by somebody famous, or made by somebody brilliant. Letting me play on it is fun and informative to the extent that I can feel the movement of the keys but this isn't going to tell me much about what the piano was, the huge range of different styles of music it gave rise to, the social and cultural conventions of its use, the virtuoso performances, and so on. Wouldn't it be wonderful to have recordings of Beethoven or Mozart actually performing? We need to make sure we preserve the Beethovens and Mozarts of gaming while there is still a chance."

Cifadi's advice to game-makers is plainer and has the urgency of an archivist watching in dismay as the present burns up as it passes into the past. "Backup, backup, backup," he says. "I say: don't worry about the tough stuff -- as in, making the games run again. Right now, just keep what we have safe. Document everything. Put it somewhere secure. Then let the future deal with how to get it working."