The All-Consuming Emotions of Food in Video Games

How food comes alive in Battle Chef Brigade, Overcooked, and Consume Me.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

Battle Chef Brigade has nearly 200 recipes. There's mapo tofu, noodle soups, steamed buns. You'll find miguelitos, moussaka, and fried rice. Recipes change depending on the ingredients used—they're not things you'd find in your backyard—and are tailored toward the chef creating it.

In Battle Chef Brigade, food is in excess and of indulgence. Chefs from around the game's world collapse on an Iron Chef-style cooking tournament wherein entrants have to battle the ingredients they're about to sauté. As if it were straight out of a Hayao Miyazaki movie, the fare is awash with cartoon realism: colorful, steaming, and often with a touch of fantasy. Battle Chef Brigade is taking food seriously. It's telling a story about a hunger not only for the food it serves up, but for its community, culture, and complexity.

Food is often seen in games as a means of survival, mostly as health. A piece of bread stolen off a vendor's table in Skyrim will grant you two health; the cabbage stew at the tavern will grant you 10. In The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild, the spicy pepper steak will take the edge off of cold weather. A game like Castlevania: Symphony of the Night has a huge inventory of food items, many of which are dropped after knocking out enemies. While the enormous variety adds an element of immersiveness into Castlevania, it's often nothing health or a novelty.

Though none of these games' food systems could be considered simplistic, they have a narrow view of eating; food is health, and eating is the mechanic in which it's used. It's easy to see food only as a function of survival, but there’s a whole breadth of games—Trinket Studios' Battle Chef Brigade, Jenny Jiao Hsia's Consume Me, and Ghost Town Games' Overcooked—that expand on what food can do in games.

Allez Cuisine!

Like Star Ocean 2's cooking master mini-game, Battle Chef Brigade uses cooking as the theme instead of the mechanic. Both games center on the fast-paced cooking tournament, albeit through different avenues. While Star Ocean 2 has the player clicking through menus, Battle Chef Brigade employs a "match three" system that mimics stirring a pot.

"We started entirely from watching cooking competition shows and wanting to make an action game that allowed for improvisation, creativity, and [the] scary timer we saw on those shows," Trinket Studios president Tom Eastman tells me. "Figuring out a set of mechanics that could feel like cooking without players being able to lick their screens was a tough prototyping process."

Though Battle Chef Brigade has a ton of recipes, none of them are immediately apparent to the player, and that's on purpose. Creativity and making do with the abundant ingredients of the land are essential to the game's success.

"Our desire to make a cooking game about improvisation instead of recipe-following really guided us away from most cooking games," Eastman says. "That was the key insight from cooking competitions that we felt was completely missing from games."

At one point during the game, the theme of abundance pivots towards a danger within that bounty. The food source, while still available in droves, has become tainted, which brings horror to the game's land. The food that once brought joy to Battle Chef Brigade's world is now a source of fear for the game's characters.

Consuming Life

But if Battle Chef Brigade is about abundance, Hsia's Consume Me is about control. The indie developer's in-progress game, along with a few of her subsequent games like Hungry Buddy, explore varying dynamics between people and the food they eat. "There are so many different emotional responses that someone can experience when it comes to eating," Hsia says. "To me, and to a lot of other people, I believe food is more than just a necessity for survival."

Consume Me (which is not available yet, though you can play some of Hsia’s early prototypes for the game on itch.io) is a culmination of Hsia's ruminations of the complexities of human experiences with food. In particular, Consume Me's concerned the twisted ways food and eating can be a haven for control of one’s life. Meanwhile Hungry Buddy exists on the opposite spectrum, wherein food is communal and often joyous.

"[Food] can bring so much pleasure and joy," Hsia says. "Like, think about the instance when you’re out partying at 3am, drunk and feeling hungry. A greasy slice of pizza seems pretty great."

The complexities of food also relate back to fear, though. A mind consumed by food-related fear can often twist realities. Hsia describes being able to physically feel her body transform the second she ate something deemed unacceptable.

"Eventually it got to the point where rejecting food had the potential to make me feel extremely powerful and in control of my life, while succumbing to it would make me feel like a worthless piece of s**t," Hsia says. "I know that sounds sort of sick and twisted, but I guess my point is [that] our relationship with food can be funny and strange, and definitely worth examining."

Early prototypes of Consume Me saw food in a more literal sense. Players needed to stack polygonal food items on a plate to satiate their character, but without going over a calorie limit. Gameplay has since shifted to a more abstract puzzle that has players fitting Tetris-like shapes that represent food items together to reach a certain calorie allotment. Though Consume Me isn't currently playable, Hsia is documenting her development progress with the title as she experiments to get things right.

"Making games about food has shifted from trying to make a simulation about eating to exploring my relationship with food through metaphor," says Hsia. "I've grown to realize that my story can be told through a variety of ways which don’t necessarily have to be about performing direct food-related activities to get across those feelings I experienced with dieting."

Consume Me's design is intended to mimic the feel of a diet journal, wherein the player tracks food intake and calorie-burning output. The puzzle timers, which show up in Consume Me's yoga simulation mini-game, elicit the chaos of the mind of a disordered eater—the way numbers dominate a mindset and how things can quickly spiral out of control.

There's terror in the timer, just as within Battle Chef Brigade, despite the emotional output differing.

Pure Chaos

The idea that food can be terrifying in unique ways extends beyond Battle Chef Brigade and Consume Me, into Overcooked. Overcooked is a cooperative multiplayer game that tasks players with cooking and serving food. But besides that, Overcooked is chaos, pure and simple. Like Battle Chef Brigade, Overcooked is ruled by a timer. Players fight against time to chop, assemble, cook, and serve a variety of different recipes for customers: Get them in early and correct and you'll be awarded a tip. Can't beat the buzzer? Then you’ll lose a number of points.

"A big part of the challenge for us developing the game was in keeping it accessible," Overcooked developer Oli DeVine tells me. "A lot of the game was refining what the restrictions are and what people expect to be able to do; what freedoms they expect versus how much they actually require."

DeVine describes an earlier version of Overcooked that required players to assemble food in a certain order; say, you were making a burger and you put the bun down after the burger was set on the plate. That’d be wrong, and cost you points. "You could accidentally put two burgers in, or too much cheese," DeVine adds. And both of those wouldn’t make the cut either.

"It took a long time to get to a point where we could communicate a recipe to players in a minimal way," artist Phil Duncan says. "A lot of the abstractions for the way that cooking works in Overcooked are there to sort of simplify what we have to communicate. It’s just, onion soup is three onions chopped and added to a pot and in no way realistic, but it’s just much easier for players to get immediately."

Food realism isn't as important to Overcooked, just as in Hsia’s Consume Me. As long as the feeling is there, that’s important. For Overcooked, that feeling is within the chaos of cooperation—the panic of beating the clock and working with your pal to complete an order.

"It was far more important to us that the cooperation was the main mechanic, rather than the intricacies of actually cooking," DeVine says. "We wanted [players] to understand how to make something really quickly and then they could actually enjoy the level or gameplay that’s about working as a team."

Though these aren't recipes you'd find in an actual kitchen, they're recipes (and gameplay) designed to replicate the feeling, terror, and thrill of a busy restaurant.

No Longer for Eating

Food has a long-standing history in video games, whether it be from collecting cherries in Pac-Man or munching cabbage in Skyrim. Food has always been food in games; something eaten to stay alive. But games are beginning to recontextualize food's existence in the sphere. In a game like Candy Crush, colorful treats are no longer just food but an aesthetic to create puzzles, as Bhernardo Viana wrote in Kill Screen's "A Short History of Food in Video Games."

Battle Chef Brigade, Overcooked, and Consume Me are all part of a movement expanding upon the idea of food as food by showing complexity in subject matter, design, and food mechanics. Games let us play with our food in a way that's not always acceptable.

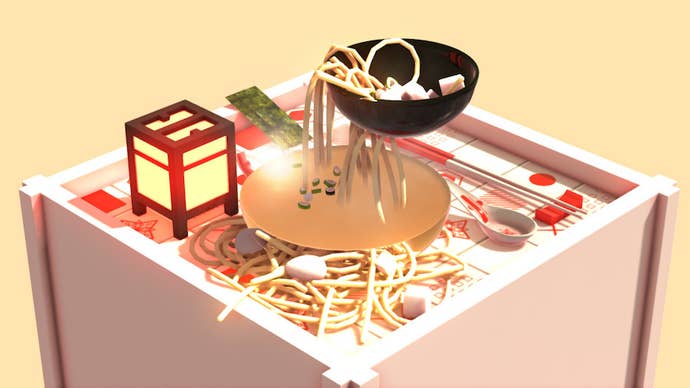

Terrifying Jellyfish, also known as TJ Hughes, takes a literal approach to the idea of playing with food in Nour. Nour lets players play with food as if it were an action figure, as Khee Hoon Chan puts it in the Unwinnable essay "The Comforts of Playing with Food in Nour." There's no objective in Nour, unless that objective is experimentation. Hughes asks his players to poke at his bubbling boba tea and fling his steaming noodles. Shower sprinkles onto a bathtub of pastel ice cream. Nour elicits emotion and hunger from its players.

When food comes alive, it transcends the idea of being a harbinger of health. The definition of what food can do in games is changing. Food isn't only for eating anymore.